5 Drafting Your Paper: Critical Deconstruction

Planning and drafting your paper are the most demanding tasks in the writing process. They require you to analyze carefully the assignment criteria, shift into a critical thinking mode, and demonstrate your ability to engage in higher order learning. Some students skip the critical thinking phase of their writing entirely by simply gathering ideas from other sources, rearranging them into some logical order, and assuming they have, thus, created the basis for a graduate paper.

However, the beauty of graduate school is that you are no longer considered to be simply a consumer of other people’s ideas. Instead, you are expected to engage critically with others’ ideas, to bring forward your own lens and experience, and to be an active participant in advancing the understanding of issues, theories, and practices in the health disciplines. The cornerstone of professional writing is the insertion of your own voice, your own critical analysis, and your own position on, or assertion about, the topic. Do not wait until you complete your program; you can begin to develop your professional voice, and to join that voice with credible, scholarly voices from others in your field of study, in your very first graduate paper.

5.1 Understanding Reconstruction

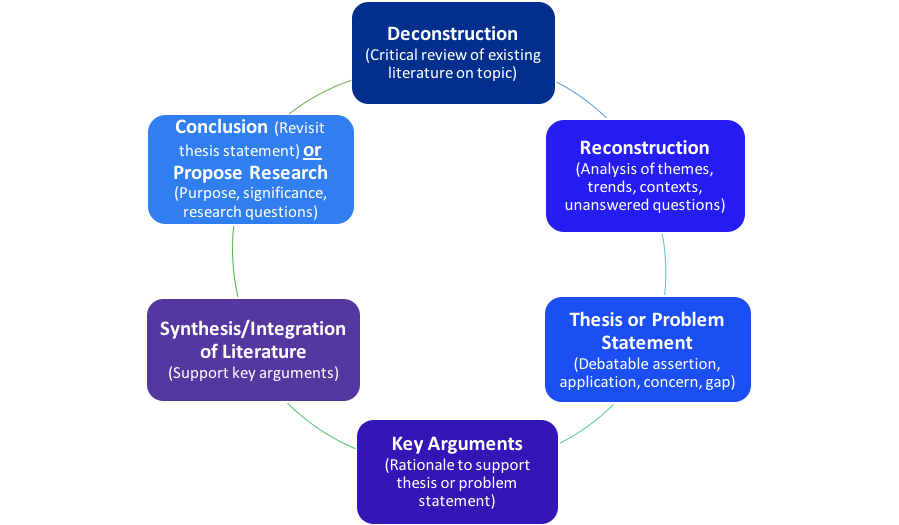

I have copied Figure 4.3.1 (below) as a reminder of the recursive and iterative process of writing a literature review or other forms of professional writing. In this section, we pick up at the point of reconstruction.

Figure 4.3.1

The Process of Professional Writing

| Click on the audio file on the left, or access the alternate text for the figure if you prefer an audio description. |

To move from your critical deconstruction of existing literature (Chapter 4) to writing your own literature review, start by stepping back and asking yourself the following questions:

- What themes do I see emerging in my summary of the existing literature?

- What issues or concepts have not been talked about?

- What relationships between ideas are not fully explored?

- What more can be said on the topic by looking at it using a different lens, a different theoretical perspective, an alternative research paradigm, or a different context?

These questions encourage you to develop your own voice, point of view, position, or perspective on the literature you have been reading. You are now moving from the process of deconstruction to one of reconstruction (i.e., putting the literature back together in an original and creative way). Deconstructing and reconstructing the professional literature is a process you will each continue to engage throughout your graduate program and throughout your careers as scholar-practitioner-advocate-leaders.

5.2 Structuring Your Literature Review

Literature reviews can be structured to accomplish different purposes even though they draw on (and reconstruct) the same overview or summary of existing literature. Regardless of the route you choose to complete your graduate program, writing a literature review effectively is a skill you are expected to develop. There are two basic purposes for a literature review: (a) as a rationale or justification for research (e.g., in a thesis proposal, or in the introduction to a research article) or (b) to support a conceptual or theoretical argument (e.g., in a course assignment, or in other non-research-based articles for publication).

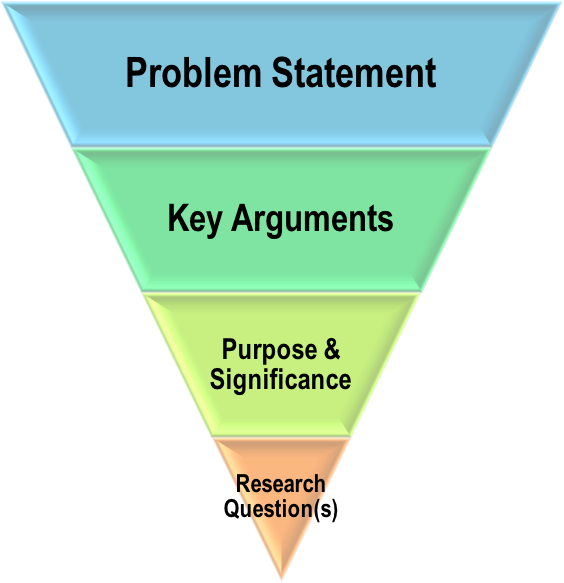

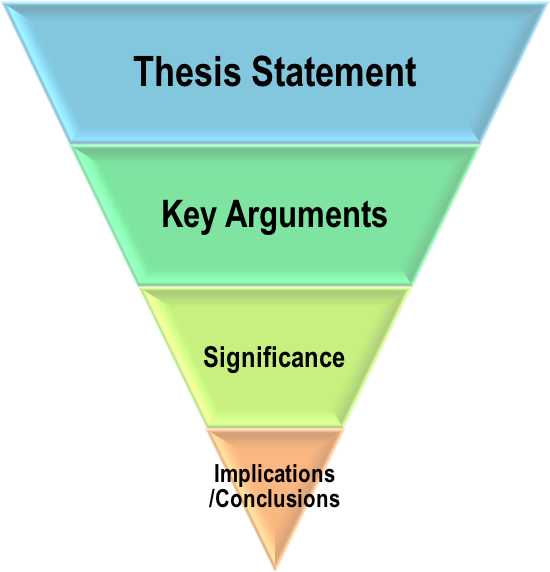

In either case, the basic structure of a literature review is similar; it leads the reader from a broad thesis or problem statement, through a series of key arguments, to a particular conclusion (see Figure 5.2.1). In the case of a literature review that is used to justify research (i.e., a thesis or research study proposal), the conclusion reached is the research question(s). Where the literature review supports a conceptual or theoretical article, the conclusion is usually related to implications for practice, advancement or critique of theory, application of a particular construct or principles, and so on.

Figure 5.2.1

Basic Structure of a Literature Review for Research Versus Conceptual or Theoretical Papers

| Literature Review as a Foundation for Research | Literature Review as a Theoretical or Conceptual Paper |

|

|

| Audio version: | Audio version: |

As you can see from the diagrams above, problem or thesis statements provide a broad starting place for your writing. As you build your arguments, you progressively narrow the focus to lead logically to either (a) your research question(s) or (b) the implications and conclusions you want to present to readers. In Table 5.2.1 (below), the same assertion is used as a problem statement and a thesis statement to provide a foundation for (a) a literature review to justify potential research and (b) a conceptual literature review. Notice how much of the content in black applies to both writing projects. The content in blue shows areas where your writing might diverge based on the different objectives of these two literature reviews.

Table 5.2.1

Content Comparison of Literature Reviews for Research Versus Conceptual or Theoretical Papers

|

Structure |

Research Literature Review |

Theoretical or Conceptual Literature Review |

| Topic | Social justice action in counselling | |

| Problem or thesis statement | Healthcare practitioners are not well-prepared to engage in social justice actions with, or on behalf of, their clients/patients, which may limit their ability to respond in an effective and culturally sensitive way. | |

| Key arguments |

|

|

| Purpose of study | To identify the competencies that students need to address social injustice effectively with, or on behalf of, their clients/patients. | N/A |

| Significance | Locating the problem within the client/patient risks blaming them for their misfortunes, inadvertently engaging in cultural oppression, and supporting an unjust status quo. Providing students with advocacy and other competencies supports the goals of building a just society and preventing problems associated with social injustices. | Locating the problem within the client/patient risks blaming them for their misfortunes, inadvertently engaging in cultural oppression, and supporting an unjust status quo. Implementing advocacy and other competencies supports the goals of building a just society and preventing problems associated with social injustices. |

| Potential research questions

OR Implications and conclusions |

|

|

The bottom line is that, as scholar-practitioner-advocate-leaders, you are responsible to respect and mirror the body of literature in the health disciplines, and you are also called to contribute to that body of literature. You might do this through engagement in research, or you might do this by contributing a theoretical or conceptual article to a journal, writing for a professional magazine, or presenting your work at a conference or a professional meeting. In each case, you may find this basic structure of a literature review helpful as a guide for your writing.

5.3 Developing a Thesis or Problem Statement

Now that you have a sense of the big picture of what is involved in a writing a literature review, and you have gathered enough information from the professional literature to get a clear sense of what you would like to say about the topic, I recommend that you take a break from your research to craft a thesis/problem statement for your paper. A thesis/problem statement is a sentence (or two) that tells the reader what you intend to argue about a particular topic. It is the main assertion or central position that forms the backdrop against which the relevance of everything else in your paper is assessed.

Let’s pick up on the objectives from Table 4.1.2 (Section 4.1) to differentiate between the objectives of a paper and its thesis or problem statements. Notice in Table 5.3.1 below, the thesis statements are also aligned with the level of learning targeted.

Table 5.3.1

Coordinating Thesis or Problem Statements with the Objective of the Paper

|

Level of Learning |

Objective |

Thesis or Problem Statement |

| Analysis | The purpose of this paper is to critically analyze the similarities and differences between an individualistic and an ecological approach to client/patient care. | Although there are some similarities between the individualistic and ecological approaches to client/patient care, the core values, locus of control, and locus of intervention are substantively different. |

| Synthesis and evaluation | My objective in this paper is to build a solid case for an ecological approach to patient/client care based on best practices and clinical research. | An ecological approach to patient/client care must begin with a systems level analysis of the presenting concern, engage the patient/client actively in intervention/treatment planning, attend to the impact of social determinants of health, and build in inter-professional collaboration where appropriate. |

| Commitment | In this paper, I intend to reflect on, and position, my values and beliefs about how to best care for each unique individual I encounter. | As a health care practitioner, I embrace the values of the ecological approach to patient/client health (i.e., respect, collaboration, and social justice); however, I struggle to reconcile them with some of my core personal/professional values for individual patient/client care (i.e., self-responsibility, practicality, immediacy of intervention/treatment, and personal autonomy). |

You will notice that a number of different thesis statements have been drawn from the topic, Approaches to Client/Patient Care. The thesis statement depends on (a) the objective of the paper, (b) what you discover in your preliminary research (deconstruction of the professional literature), and (c) your interests and opinions about the topic.

To explore further the difference between the topic, objective (purpose), and thesis of your paper, you may want to review the following Web resources:

-

Purdue University. (n.d.). Developing strong thesis statements. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/establishing_arguments/index.html

-

Purdue University. (n.d.). Tips and examples for writing thesis statements. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

-

University of Wisconsin. (n.d.). Developing a thesis. https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/process/thesis/

-

University of Wisconsin. (n.d.). Thesis and purpose statements. https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/process/thesis_or_purpose/

Each thesis/problem statement can be evaluated against the following criteria:

- A thesis or problem statement is usually a single sentence.

- It focuses on one central idea.

- It identifies a gap between what is known and unknown; between current practices and potential practices; between current thinking and new ways of conceptualizing problems, issues, or practices.

- It focuses on an area of emergent concern or debate.

- It makes an arguable claim or assertion about the topic.

- In most cases, the assertion is debatable.

- A thesis/problem statement is specific enough to provide direction for the paper.

- It identifies the unifying thread for the arguments that follow.

- It narrows the focus or scope of the argument (i.e., breadth and depth) of the paper.

- It alerts readers as to why your research, concept, or theory-based argument is important.

What should be clear from the list above is that the final writing of your literature review cannot be completed until after you have gathered, summarized, and critically analyzed the existing literature to such a degree that you can come up with your own thesis or problem statement. However, this is likely to be a recursive process that requires you to go back and forth a number of times between what you have learned from the literature and what you want to assert in your literature review. The result will be the unique position that you want to argue. Your position statement derives from the body of literature, but it offers something new and original.

A strong thesis or problem statement indicates to readers the single most important idea that you want to communicate, and it often provides them with a preview of how your arguments will be laid out in the paper. You may revise your thesis statement as you continue to develop your paper. Normally, you position your thesis statement prominently in your introduction, often as the last line.

Complete Exercise 5.3.2a to test your understanding of how to create a strong thesis statement. Then work through Exercise 5.3.2b to practice generating problem statements and corresponding research questions. Check out the Exercise 5.3.2b Possible Responses to ensure that you are on the right track. There are no right answers to these activities, because many different objectives, levels of learning, thesis or problem statements can emerge from a single topic.

5.4 Creating a Conceptual Framework

As you explore the professional literature or engage in applied practice contexts, you may discover that there are particular concepts and theories that shed light on the topic about which you are curious. These concepts and theories may influence how you or others think about your topic. Most graduate papers do not require you to develop a conceptual framework. However, you may be expected to do so for a research proposal in your methods of inquiry course or as part of your thesis work (if you choose that exit route). The conceptual and methodological congruence of your research plan and implementation will be dependent on your level of clarity about the lenses (i.e., concepts and theories) you adopt. You may also benefit from including a conceptual framework in other course assignments or culminating program activities. The decision to include a conceptual framework depends, to a large degree, on the topic and the objective of your writing or, if you are planning to engage in research, on how you position your research.

A framework is basically a broad structure that provides meaning and direction for your research or writing. This framework is most often built upon a number of interrelated concepts. I am using the term, concept, to refer to an abstract representation, in language, that characterizes a particular experience or phenomena. In some cases, specific concepts are already clustered together in a purposeful way within a particular theory or model. In this case, the relationships among those concepts has already been explored and articulated. Normally, the relationships between concepts in a theory are more definitive, developed, or “tested”; whereas, conceptual relationships in a model tend to be more tentative and exploratory (McConnelly, 2014). In other cases, the concepts of interest to you may be loosely interconnected, or they may not yet have been connected to the phenomenon you are interested in studying.

It is your job, as a writer and researcher, to make these connections. In most cases, you develop the connections through your literature review, and then enter into your writing or research with a conceptual framework in mind. Although the terms, conceptual framework and theoretical framework, are often ill-defined or used interchangeably in the literature (Green, 2013; McConnelly, 2014; Ravitch & Riggan, 2017), I am using the term, conceptual framework, as the broader, umbrella term (Ravitch & Riggan, 2017). This choice is based, in part, on the argument by Green (2013), who proposes that theories are rarely used whole to support research; rather, particular interrelated concepts are highlighted to support a specific purpose within any study. I define a conceptual framework as a visual representation of the relationship between theories, models, and concepts (as well as variables in the case of quantitative research) that makes transparent the way in which you, as the researcher, are thinking about the various elements that influence your research questions and research design. Ravitch and Riggan (2017) reinforce this definition by arguing that to create a conceptual framework “you must critically read and make connections between, or integrate and synthesize, existing work related to your emerging research topic and its multiple theoretical and practical contexts” (p 11).

Your paradigmatic position (i.e., the assumptions you make about the nature of reality, what is knowable, and how knowledge is created) also needs to be stated in your research; however, it is not typically represented directly in the conceptual framework. Having said this, the paradigm that you gravitate towards (e.g., positivist/postpositivist, constructivist/interpretive, critical/emancipatory/transformative, Indigenous, pragmatic) may have considerable influence on the theories and concepts you highlight in your conceptual framework and how you position the relationships among them (Green, 2013; Mertens, 2015). For example, addictions research among the poor may be positioned quite differently if an emancipatory/critical lens, rather than a positivist/postpositivist lens, is applied to the research. The former is much more likely to draw on concepts such as social determinants of health, equity, social injustice and to position the locus of research at the level of systems rather than at the level of the individual. Your paradigm might also influence the nature of the relationships you envision among the concepts (e.g., causal, correlational, explanatory).

Many writers and researchers articulate a conceptual framework during the literature review and problem exploration stage of the research. Many more could, and should, have done so at that point to make their thinking about the context of the research more transparent to consumers. However, there are some methods of inquiry in which one might argue that the conceptual framework is intended to arise from the research, because the goal is to generate theory (e.g., grounded theory) (Green, 2013; McConnelly, 2014). It is important to be aware that, even when then the conceptual framework is provided up front, it may be modified, clarified, or expanded upon based on the research outcomes.

Take, for example, the broad topic of graduate studies in the health disciplines. A literature review might reveal a number of important concepts (e.g., critical thinking, reflective practice, cognitive complexity), which all influence the development of professional competency. In addition, you might encounter some important principles from adult learning theories (e.g., experiential learning, practice-based learning, authentic assessment). All of these elements influence your conceptual framework. In this case, they are also all consistent with a constructivist paradigmatic lens. Figure 5.4.1 provides an example that illustrates how a visual representation of the conceptual framework makes the interconnections among these concepts clearer.

Figure 5.4.1

Hypothetical Conceptual Framework for Understanding Competency Development Among Graduate Students

To expand further your understanding of conceptual frameworks in research, review the following YouTube videos:

© NurseKillam (2013, November 3)

© NurseKillam (2014, November 6)

5.5 Building Your Argument

Now that you have a clear thesis or problem statement for your paper, your task is to create a convincing argument in support of that overriding assertion or position. A graduate professional paper is organized according to a set of key points or arguments; it should not simply follow a topic outline based on your gathering of ideas from the professional literature as discussed in Chapter 4. The arguments you make to support the thesis of your paper should be clear, succinct, and well-organized. This requires you to take a step back and consider how best to support the thesis or problem statement you have generated, as expressed in the following Faculty of Health Disciplines (FHD) Program Outcome.

Thesis & arguments. Articulate and support an original thesis and sustained, well-reasoned arguments.

Building Effective Arguments

The example in Figure 5.5.1 is drawn from my own research and might form the foundation for a paper I write on the topic of multicultural counselling and social justice. Apply the principles we have examined above to the objective and thesis statement. Then consider the key arguments (in bold) and subpoints I have chosen to support those arguments. Both reflect my critical analysis of the literature and my own professional experience and perspectives (i.e., my voice).

Figure 5.5.1

Building an Effective Argument

Topic. Multicultural counselling and social justice

Objective. To evaluate the positions of multicultural counselling and social justice in the profession of counselling.

Thesis Statement. Multicultural counselling and social justice are inextricably intertwined; both are central to competent and ethical practice with all clients.

Arguments.

- All counselling is multicultural in nature, and culture-infused counselling forms a foundation for working with all clients (Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016).

- Personal cultural identity reflects a wide range of factors, including gender/gender identity, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, ability, religion, socioeconomic status, and their intersections (Nassar-McMillan, 2014; Sinacore et al., 2011).

- Culture is co-constructed through the interface of client and environment and in the relationship between counsellor and client (Bava et al., 2018; Christopher et al., 2015; Combs & Freedman, 2018).

- The counsellor, the client, and the counselling relationship are all influenced by the interface of client–counsellor cultural identities (Paré, 2013; Socholotiuk et al., 2016).

- Infusing awareness of culture into the counselling process brings these influences into awareness and facilitates more culturally relevant and appropriate practices (Ratts et al., 2015, 2016; Paré, 2013).

- The interface of client–counsellor cultural identities cannot be fully appreciated without deliberate attention to relative social locations (Collins & Arthur, 2018; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016).

- Nondominant cultural identity is defined, not by relative population numbers, but by relative positioning in personal, interpersonal, and group power and privilege (Arthur & Collins, 2016; Trahan & Lemberger, 2014).

- There are significant discrepancies between the social, economic, and political positions of dominant and nondominant cultural groups in North America (Arthur & Collins, 2016; Nejaime & Siegel, 2015).

- Individuals and groups who do not form part of the dominant culture are more likely to experience social exclusion, including barriers to services and resources, cultural oppression and marginalization, as well as limitation to social, economic, and political inclusion and advancement (Allan & Smylie, 2015; Singh & Moss, 2016; Talley et al., 2014).

- In contrast, individuals and groups who reflect the dominant culture often experience unearned privileges by virtue of their social location (Audet, 2016; Paré, 2013; Trahan & Lemberger, 2014).

- Without active attention to the relative privilege of counsellor and client, it is impossible to build an effective therapeutic relationship with clients, and there is a significant risk of inadvertently perpetuating cultural oppression within the counselling process (Houshmand et al., 2017; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016; Yarhouse & Johnson, 2013).

- Awareness of the complexity of client cultural identities and social locations necessitates critical analysis of client contexts (Audet & Paré, 2018; Ratts & Pedersen, 2014) and client experiences of social injustices (Dollarhide et al., 2016; Scheel et al., 2018) in both case conceptualization and intervention planning.

- . . .

- . . .

- . . .

- Engaging clients actively in a collaborative and co-constructive counselling process optimizes the potential for minimizing power differences (Combs & Freedman, 2018; Mizock & Konjit, 2016) and ensures the counselling process is client-driven (Brown, 2010; Collins & Arthur, 2018; Fitzpatrick et al., 2015).

- . . .

- . . .

- . . .

Although I am drawing on the research I have conducted in this area, each of the key points and subpoints are in my own words. They are my analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of the literature. This does not mean I do not need to give credit to the sources I have reviewed. I inserted them to ensure I do not lose track of whom I need to credit to support my ideas. Think of each of the key points or arguments in Figure 5.5.1 as the foundation for a paragraph or set of paragraphs in your paper. As I created my argument above, I systematically and purposefully organized each of the key points to build my overall argument. I had to reorganize my argument a number of times to make sure there was a logical flow. In this case, I have opted to move from broad assertions down to more narrowly focused points. I corrected a few flaws in the progression of my ideas as I read them through sequentially.

A solid argument is composed of an organized and logical set of the following elements.

- Assertions about, or points of view on, a subject. You will break down your overall argument into several key points or arguments, but each should be clearly connected to the position (thesis/problem statement) of your paper.

- Evidence to support those assertions or points of view. You have built the foundation of your arguments by gathering information from the body of professional literature, and now you will use that research to support the key points in your draft paper. Your challenge is to take a critical look at that evidence to ensure that it supports your thesis and is presented in a systematic and logical fashion.

- A response to counterarguments. In some cases, there may be arguments against your thesis/problem statement that you need to address in order to provide your reader with a complete picture. By systematically identifying and responding to these counterarguments you demonstrate critical thinking and strengthen your overall argument.

To learn more about building effective arguments, you may want to review the following resources.

-

Massey University. (2019). Constructing an argument. http://owll.massey.ac.nz/study-skills/constructing-an-argument.php

-

Purdue University. (n.d.). Organizing your argument. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/establishing_arguments/organizing_your_argument.html

-

University of Northern California. (2019). Argument. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/argument/

Differentiating an Argument from a Topic Outline

It is important to distinguish between building an argument, which is essential in graduate and professional writing, and creating a topic outline (which may have been acceptable in some undergraduate contexts). Contrast the argument outlined in Figure 5.5.1 with the topic outline in Figure 5.5.2. The latter is organized by topic rather than argument and does not clearly lead the reader to a logical conclusion or position (thesis).

Figure 5.5.2

A Topic Outline

Topic. Multicultural counselling and social justice

Objective. To evaluate the positions of multicultural counselling and social justice in the profession of counselling.

Thesis Statement. No thesis statement created.

Topics.

- Nature of counselling

- Personal cultural identity

- Co-construction of culture

- Interface of client–counsellor cultural identities

- Infusing awareness of culture

- Social location

- Definition of nondominant cultural identity

- Discrepancies between dominant and nondominant cultural groups

- Social exclusion

- Unearned privilege

- Attention to relative privilege of counsellor and client

- Case conceptualization and intervention planning

- . . .

- . . .

- . . .

- Collaborative and co-constructive counselling process

- . . .

- . . .

- . . .

It would be very difficult to write a solid argument based on the topic outline in Figure 5.5.2. You would be much more likely to end up with a descriptive paper (i.e., one that demonstrates only knowledge and comprehension), rather than a paper that takes a particular position and systematically supports that position.

Table 5.5.1 provides an example of an argument on the topic of our food supply and compares it to a topic outline. I have stated each key point clearly in one sentence. The logical flow between the key points is clear. I have nested (indented) the subpoints to make the flow of the argument clear. I based this sample argument on a book I was reading.

Table 5.5.1

Comparing an Argument to a Topic Outline

|

Key Points in An Argument |

Topic Outline |

| Thesis statement. The large-scale industrialization of food production is seriously compromising the quality of our food, and without a revolution of the masses both human beings and the planet will experience dire consequences. | Introduction |

| The industrial revolution has opened doors to new methods and models of food production; however, innovation does not always mean increased quality. | Industrial revolution and food |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Changing the values that drive production has resulted in serious consequences for the quality of food we eat. | Impact on food quality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Both the loss of nutritional value and the addition of chemical toxins are already having dramatic effects on human health. | Impact on human health |

|

|

|

|

Note. Adapted from “The end of food: How the food industry is destroying our food supply – and what you can do about it,” by T. F. Pawlick, 2006, Douglas & McIntyre.

Critically analyzing, and extrapolating upon, the argument presented by another writer, as I have demonstrated in Table 5.5.1, is a good way to summarize the ideas that you may want to incorporate into your own paper. It forces you to think critically and to synthesize the information into succinct statements (using your own words). However, do not use this as the argument for your paper as if it reflects your own ideas. Remember, copying another author’s argument is a form of plagiarism.

Refining Your Arguments

Coming up with a clear thesis or problem statement and logical flow of arguments in support of that assertion requires time and energy. However, making this investment will improve your writing exponentially. Consider these additional tips for refining your arguments. In this case, I have worded these in relation to a literature review for the purpose of a research proposal (recall the structure of literature reviews for various purposes in Section 5.2), although the same basic principles apply to all professional writing.

- Arguments should demonstrate logical flow from the problem statement to the research purpose.

- They should be distinct, succinct, and clearly stated.

- Arguments should not have significant leaps between them; if there are any such gaps, they may need to be filled in with an additional key point.

- They should be grounded in the body of literature within the health disciplines.

- They should be complete. Ask yourself if you might need to add anything else to enhance the flow or comprehensiveness of your argument?

- Arguments, like thesis statements, are “arguable” assertions; a statement of fact is not an argument, although it can support, or provide background for, an argument.

- They are strongest when phrased proactively or positively (i.e., these practices promote fairness versus these practices are not unfair).

- Arguments are best phrased in the first person, active voice, because you are expressing an informed opinion and your original thinking about the topic.

- Each key point in your argument should build on the previous one and be conceptually congruent with the problem statement.

- Arguments can typically be expressed in one sentence (preferable) or two short, succinct, and clear sentences; if you write a paragraph, the main point will be difficult to discern.

- Each element of your argument should reflect only one key point; avoid making two arguments together.

Consider the sample argument in Figure 5.5.3, which is intended to form the foundation for a research proposal. Apply each of the principles above to critique the quality of the proposed argument. In this case, a problem statement is used (in lieu of a thesis statement), and the arguments lead logically to the purpose of the study and potential research questions.

Figure 5.5.3

Drafting an Argument for a Research Proposal

Topic. Stresses on graduate students in the health disciplines

Problem Statement. Graduate programs may inadvertently erect barriers to student academic and long-term career success by failing to attend to the struggles of graduate students experience as they endeavor to manage family, work, and other external demands (Markus et al., 2018; Stewart & Lee, 2020; Von Tromp, 2019).

Arguments.

- In many professions, including certain health disciplines, graduate education is no longer an option; it is a core requirement for entry to the profession (Hannah et al., 2019; Centre for Graduate Consultation [CGC], 2020). The accessibility of graduate education has not kept pace with entry-to-practice requirements (CGC, 2020; Estefan, 2017; Ryan & Burke, 2018).

- In recent years, the economic downturn has resulted in increased tuition costs concurrent with increased financial stresses on individuals and families (CGC, 2020; McLeod et al., 2019). Students face a more difficult balancing act, and must carefully assess the cost-benefit analysis of graduate education (Jerry, 2019).

- The average age of students entering most graduate programs has also increased (CGC, 2020; Ministry of Advanced Education [MAE], 2018), which means that many of them have immediate and extended family responsibilities, employment and related economic, time, and relational demands in addition to the demands of graduate school (Adveral & Clock, 2018; Bailor et al., 2016; Winterowd, 2018).

- Student life has always come with its own stressors; however, higher levels of stress may be reflected in trends towards increased (a) early withdrawals from graduate programs (MAE, 2018; Zwierner, 2020), (b) physical and mental health challenges among graduate students (CGC, 2020; Lowe et al, 2019), and (c) conflicts and tensions with peers and/or instructors (Jerry, 2019).

- Graduate health disciplines students (e.g., developing counsellors) are expected to engage in deeper levels of personal development, as part of their educational process, than liberal arts or science students, for example (Wong & Jackson, 2016). This intense reflective process may be challenging when one is under stress, and it may itself increase overall stress levels (Audette, 2017; Guielle et al., 2018; Sampson & Winterowd, 2019)

- Little recent research has been conducted specifically on graduate students in the health disciplines from either the perspective of supports for success or the elimination of existing barriers (CGC, 2020; MAE, 2018).

Purpose of Study. The purpose of the proposed study is to identify both student and program factors that pose barriers to the academic and long-term career success of graduate students in the health disciplines.

Potential Research Questions:

- What do graduate students in the health disciplines perceive as the barriers to their success within both their own lives and graduate programs?

- To what degree are the barriers to success faced within graduate programs in the health disciplines a result of student factors versus program factors?

Note. The sample problem statement and argument provided above have been constructed for the purpose of this activity and do not necessarily reflect the current professional literature. The citations provided are fictitious.

The purpose of this exercise is to practice developing clear key points in an overall argument. Take each of the thesis/problem statements below and generate a series of key points (arguments) to support that assertion. Notice that on the topic of developing writing skills, it is possible to argue two very different positions. I deliberately set up two contradictory thesis/problem statements to demonstrate that these must be arguable. Organize your key points according to a logical flow that persuades the reader that your thesis or argument is worthy of their consideration.

Thesis/problem statement 1. Developing solid writing skills early on will facilitate success in both graduate education and professional roles.

Thesis/problem statement 2. The emphasis on writing skills in graduate programs distracts from the central mandate of developing applied professional competencies.

In Figure 5.5.4 (below), I provide a brief synthesis of an assignment that requires students to write a literature review for the Methods of Inquiry course in the FHD Master of Counselling program. I then provide a video, designed to support that assignment, in which I reinforce what it means to draw on the professional literature to create a problem statement and a set of arguments to support future research. This video reiterates the content provided in this section.

Figure 5.5.4

Sample Research Proposal Assignment

The content below is excerpted from the literature review assignment instructions in the Athabasca University GCAP 691: Methods of Inquiry course.

- Choose a topic within the fields of counselling and psychology. Then glean what is already out there in the literature, and develop your own ideas on the topic. Start by critically analyzing at least 15 peer-reviewed journal articles on your topic (7 must be research studies, and all must be either recent or seminal articles). You will be graded on your appropriate selection of sources.

- Organize the content from these articles in a meaningful way. Try to develop a system that will allow you to see the interconnections across articles as well as the gaps within and between them.

- Create an original problem statement as the central thread for your writing. Then delineate a clear set of arguments (typically 5‒8) to form the foundation of your literature review.

- Demonstrate awareness of professional ethics and respect for cultural diversity and social justice in your problem statement and arguments. Professional writing is evaluated on both the quality of the argument and the nature of the argument, which must fit within the values of the profession.

- Flesh out your argument(s) by integrating, synthesizing, citing, and critiquing the literature you reviewed.

- Ensure that you provide appropriate citations for all of the ideas you pull from the literature, and support all of your ideas with appropriate references to the professional literature.

- Define and discuss any major concepts or theoretical frameworks you reference.

- Draft an introduction and a conclusion, ensuring that your problem statement is clear and that you contextualize it within the existing literature. The conclusion should reference your objective in researching the topic area.

For those who prefer to read this content, please review the MS Word transcript.

Consider the problem statements and arguments for the research proposals (linked below) to reinforce your learning. Attend carefully to the ways in which the arguments lead logically toward the proposed research study. Consider how you might instead use the same arguments for conceptual/theoretical paper by listing implications and conclusions, instead of the purpose of the study.

Practicum Supervision in Psychology: A Call for Mandatory Training

5.6 Synthesizing and Integrating the Professional Literature

Synthesizing and Integrating Effectively

At this point in your writing process, you have a clear argument drafted with key points and subpoints to support your thesis or problem statement. Make sure that each paragraph (or group of paragraphs) relates to one of the key points in your argument. You may want to copy each of your key points to the first line of the paragraph that elaborates on that point. The key point becomes the topic sentence for that paragraph and ensures that the reader can easily follow the flow of your argument. Your next task is to integrate the ideas of others effectively to support your arguments to meet the following FHD program outcome.

Synthesis & Integration. Integrate, critique, and synthesize the professional literature.

There are several reasons why it is important to cite, accurately, the work of others throughout your paper.

- You are making a contribution to the body of literature in your discipline when you write a scholarly paper. It is important that this contribution be documented clearly so that others can link your ideas to that broader literature base.

- You are presenting ideas that readers may want to explore further. Properly citing your sources allows them to find the complete reference in your reference list and locate the original source for themselves.

- You compromise your scholarly integrity and put yourself at risk of plagiarism, as noted in Chapter 2, when you fail to systematically and accurately identify your sources.

- You strengthen the arguments you are making by integrating and synthesizing the professional literature, effectively and ethically.

If you have effectively tracked the sources of your ideas, you may have supported some of the key points and subpoints in your argument already; in other cases, you may need to revise the paragraph(s) to provide sufficient evidence to support the key point. You can go back to the ideas you generated and organized through your preliminary research on the topic (Chapter 4), or you can search out additional sources to inform and support your points.

Students sometimes have difficulty understanding how the objective of a paper, which addresses the nature of the assignment and levels of learning targeted, influences how they integrate material from other sources and how they word the points and subpoints in their paper. Table 5.6.1 provides some examples of the kinds of statements you might make if you were attempting to demonstrate various levels of learning (Bloom, 1956). Read the descriptors associated with each level, and then analyze the statements on the right to see how well they reflect these criteria. Notice how the nature of the statements changes as the level of learning targeted advances. Please note that it is difficult to accomplish all the goals associated with a particular learning outcome in one or two statements; these are intended simply as examples. I have not included the skills domain, because this would rarely be assessed through a written assignment. I have added fictional citations to reinforce the importance of synthesizing the professional literature to support your points. Even when you are speaking about your own attitudes, beliefs, and values (i.e., affect), it is important to tie your assertions to the professional literature.

Table 5.6.1

Synthesis of the Literature To Reflect the Level of Learning Targeted

|

Cognitive Domain |

||

|

Level of Learning |

Descriptors |

Synthesis of Literature |

| Knowledge |

</td > |

The social determinants of health include racism, poverty, poor housing, lack of access to education, and social isolation (Brown, 2015; Frankel, 2012; Young & Pedersen, 2015). |

| Comprehension |

|

These issues are considered social determinants of health because they are most often outside of the individual’s control (Brown, 2015), and they affect diverse groups in society differently (Collins & Anderson, 2013). |

| Application |

|

The social determinants of health provide a useful conceptual model for arguing against a purely individualistic approach to patient/client care (Dunkel et al., 2014; Young & Pedersen, 2015). For example, framing poverty as a social determinant of health places responsibility on society to effect change in the inequitable distribution of resources rather than making it the individual’s responsibility to rise above these inequities (Dunkel et al., 2014; Jamison, 2013) |

| Analysis |

|

All of the negative social determinants of health share these commonalities: they apply to groups of individuals, the influence across groups differs, groups with less power and privilege are more vulnerable to, and more negatively affected by, them (Dunkel et al., 2014; Edgeworthy, 2010; Williams & Grant, 2011). The social determinants of health are a reflection of broader social narratives about who is more deserving of access to resources and services (Williams & Grant, 2011). These narratives are often built on misrepresentations of justice and equality (Brown, 2015; Frankel, 2012). |

| Synthesis |

|

A logical extension to the social determinants of health argument is that the responsibility for change rests predominantly with those of us who benefit from inequities and social injustices (Frankel, 2012; Nuttgens, 2016). Society will be able to shift the balance of power and privilege only by increasing awareness of these inequities (Frankly, 2016) and fully embracing social justice (Brown, 2015; Nuttgens, 2016). |

| Evaluation |

|

Although I am arguing in favour of applying a social determinants of health lens to our understanding of health problems and solutions, this approach is not without its weaknesses. It potentially paints groups of people with the same brush and masks individual differences; it opens the door to top-down interpretations of change; and it may overwhelm and lead to immobilization rather than action (Dunkel et al., 2014; Edgeworthy, 2010; Williams & Grant, 2011). It is also difficult to argue against the idea of social justice; therefore, it is important to break this broad concept down into specific assertions and practices to better engage in a balanced debate (Paul, 2010; Zimmerman, 2013). |

|

Affective Domain |

||

|

Level of Learning |

Descriptors |

Synthesis of Literature |

| Awareness |

|

I struggled at the outset of the course with the idea that doing nothing about racism or sexism in society is supporting the status quo (Lamonte, 2018). I did not understand that awareness without action meant I was not fulfilling my professional and ethical responsibilities. As the course progressed, however, I opened to the idea that unless I actively confront racism, sexism, and homophobia, I am supporting cultural oppression within the health professions and within the broader society (Allie, 2015; Gray, 2014; Lalande & Young, 2016). |

| Commitment |

|

As a result of this new awareness, I have begun to seek out opportunities to apply what I have learned in practice. I have joined the Social Justice Chapter of the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, and I am volunteering in a local immigrants’ society. I am also actively confronting these *isms by challenging oppressive comments, practices, and policies as they arise (Allie, 2015; Lalande & Young, 2016). For example, I have volunteered to rework our intake form to be more culturally sensitive. I have set a goal for myself to identify one specific task to undertake each month to increase my own understanding of cultural oppression and to share that learning with others. |

Complete Exercise 5.6.1 to practice writing in a way that reflects the levels of learning targeted. Writing in a way that reflects analysis, synthesis, and evaluation may make the difference between a poor grade and a great grade on graduate papers.

Using the topic, objective, and thesis/problem statement in Exercise 5.6.1, create three different sentences for each level of learning. Remember, you do not need to address all of the criteria in each statement. Only cognitive learning is targeted in this exercise, because of the topics selected, and because this is often the aspect of writing where students have the most difficulty distinguishing among and targeting specific levels of learning.

You should now have an almost complete draft of your paper. Carefully read through it to ensure that the criteria for demonstrating critical thinking (Section 4.5) are met throughout your writing. You may want to write in the margins the levels of learning you are demonstrating with each key point: evaluation, synthesis, awareness, and so on. If you cannot clearly identify which criteria apply, rethink and rewrite that section.

Drafting Your Introduction

Now that you have pulled together the literature to support your argument, take a step back to ensure that your objective and thesis/problem statement are still a good fit with your draft of the paper. You may need to massage them a bit based on new research you have discovered or the evolution of your argument. Then you are ready to craft your introduction. Drawing on Fowler et al. (2005), at minimum, your introduction should

- introduce the topic of the paper,

- describe your objective in writing the paper, and

- state your thesis.

You may also want to

- describe why the topic is important;

- indicate your attitude toward the topic;

- provide an example, a scenario, or a dilemma to capture the reader’s attention;

- set the context or provide relevant background information;

- define key terms or concepts; and

- describe how the paper is organized (if not indicated in your thesis statement).

I typically begin by introducing the topic and stating the objective of my paper, add any additional information, and then conclude with the thesis (or problem) statement. I have crafted a sample introduction in Figure 5.6.1 based on the topic, purpose, and thesis in Table 5.6.2 below.

Table 5.6.2

Sample Topic, Objective, and Thesis/Problem Statement

|

Topic |

Objective |

Thesis/Problem Statement |

| End of life care | The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the similarities and differences between in-home and residential hospice care systems. | Both in-home and residential hospice care programs offer critical medical and psychosocial support to patients and families; however, those patients with hands-on support from family and friends experience increased quality of life, autonomy, and sense of well-being by staying in their own homes. |

Figure 5.6.1

Sample Introduction

Click here for an accessible PDF version of this image.

Complete Exercise 5.6.2 to practice drafting introductions based on the topic, objective, and thesis statements used in earlier exercises. Check out the following resource for more tips on creating an effective introduction.

-

Massey University. (2012). Essay conclusion. http://owll.massey.ac.nz/assignment-types/essay-introduction.php

Drafting your conclusion

The conclusion to your paper is just as important as the introduction. Your conclusion typically begins with a brief summary of the arguments presented. It links to your thesis or problem statement to demonstrate how the main point of the paper has been supported through the body of your writing. Rather than simply copying your thesis statement, restate it in a new and interesting way. Depending on the nature of the paper, you can then choose to include some or all of the following:

- implications or significance of the ideas presented,

- directions for further research or development,

- personal reflections or applications, or

- a call for action.

Review the sample conclusion in Figure 5.6.2 (below). It is based on the topic, objective, and thesis from Table 5.6.2, which was used to craft the introduction in Figure 5.6.1 (above).

Figure 5.6.2

Sample Conclusion

Click here for an accessible PDF version of this image.

Test your skills at building an effective conclusion in Exercise 5.6.3, drawing on the two topic, objective, and thesis sequences in Exercise 5.6.2. Be sure to use the introduction you crafted in Exercise 5.6.2 as an additional reference point. Check out the following resource for more tips on creating an effective conclusion.

-

Massey University. (2012). Essay introduction. http://owll.massey.ac.nz/assignment-types/essay-conclusion.php