Chapter Objectives

This chapter will enable you to identify:

-

- Lymphoid nodules

- Various types of lymphoid organs

- Various forms of lymphoid tissue of mucous membranes

- Various cells typically found within all forms of lymphoid tissue

Lymphoid (lymphatic) tissue is a specialized form of epithelial and connective tissue that is regularly infiltrated with lymphocytes. Lymphocytes will be distributed throughout the body in a variety of ways, including:

- Individual, encapsulated lymphoid organs

- Nonencapsulated lymphoid nodules within connective tissue

- Isolated aggregates of lymphoid cells

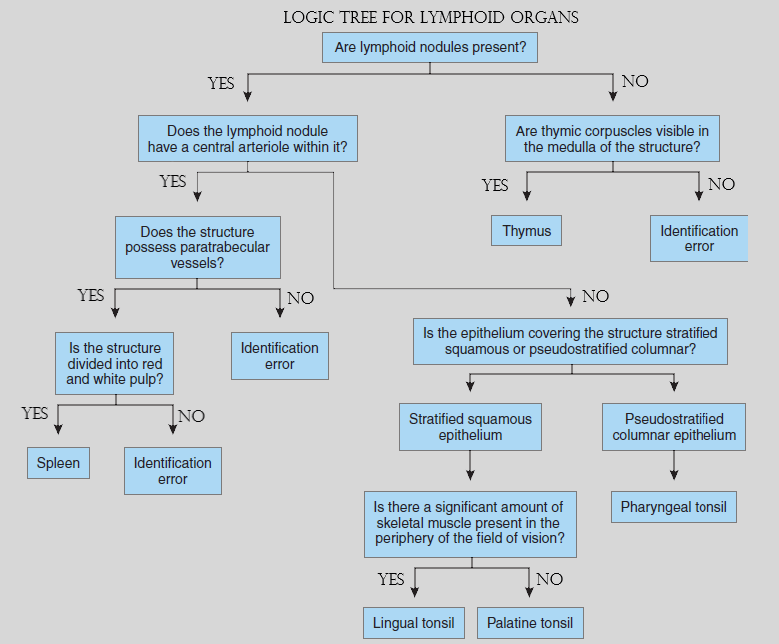

Diffuse Lymphoid Tissue and Lymphoid Nodules

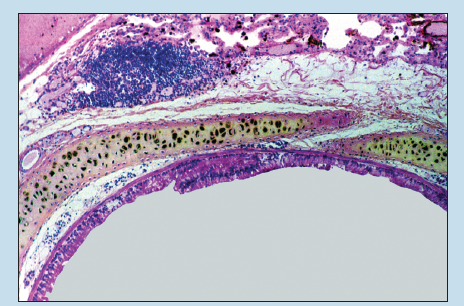

Diffuse Lymphoid Tissue

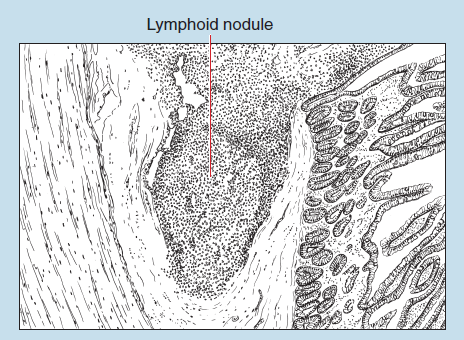

Diffuse lymphoid (lymphatic) tissue may be found within various portions of the respiratory, urogenital, and digestive systems. Figure 11-1 demonstrates diffuse lymphoid tissue in close association with a bronchus of the respiratory system. What would be an advantage of having lymphoid tissue in this region of the respiratory system?

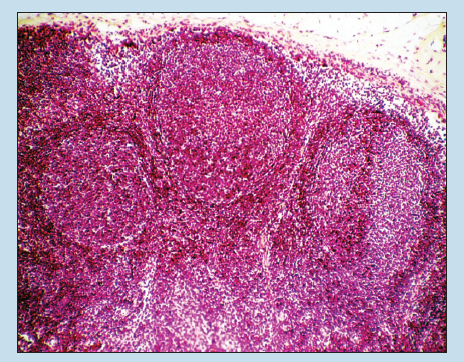

Lymphoid Nodules

Lymphoid (lymphatic) nodules, which are typically oval in shape, are aggregations of lymphocytes contained within a supporting framework of reticular fibers. There are two forms of lymphoid nodules: primary and secondary. A primary nodule is composed almost exclusively of small lymphocytes. Most lymphoid nodules, however, are secondary nodules. Secondary nodules have the following histological characteristics:

- An outer ring of small, dark-staining lymphocytes

- An inner, lighter-staining region termed a germinal center that contains larger, paler-staining lymphocytes

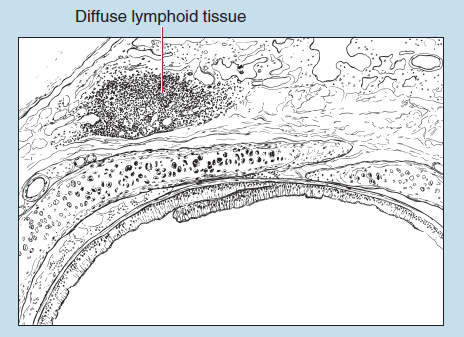

Aggregated Lymphoid Nodules (Peyer’s Patches)

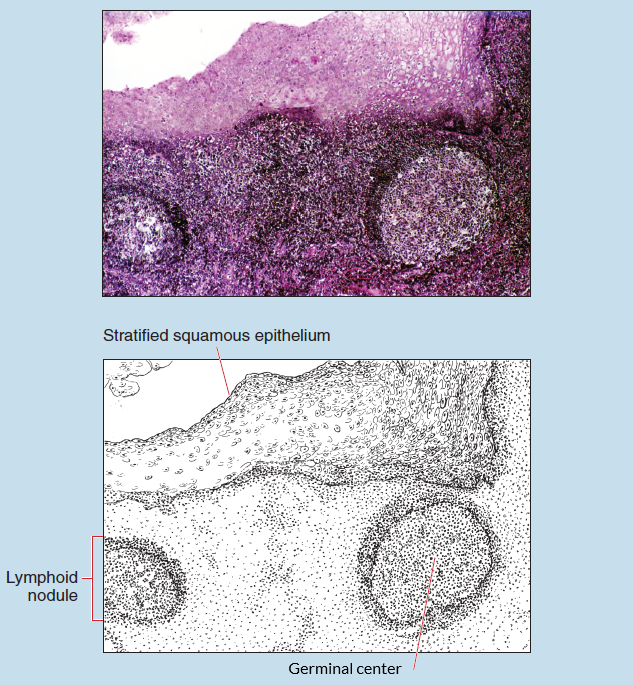

Aggregated lymphatic nodules (also termed Peyer’s Patches) (Figure 11-2) are groups of lymphoid nodules found in the ileum of the small intestine, especially near its junction with the colon. They always occur on the side of the gut opposite the attachment of the mesentery.

Each group of aggregated lymphoid nodules consists of 10 to 70 nodules lying side by side and arranged such that the entire group has an oval shape, with its long diameter lying lengthwise in the intestine. The apices of the nodules are pear shaped and directed toward the lumen. They almost project through the entire thickness of the mucosa.

The surface of the small intestine is lacking villi at the location of the nodules. As you look at Figure 11-2, it appears that villi are indeed present on the intestinal surface at the location of the aggregated lymphoid nodules. What good histological reason could be given for the apparent presence of villi immediately superficial to the location of aggregated lymphoid nodules?

Lymphoid Organs

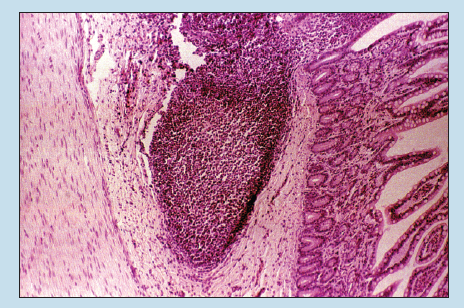

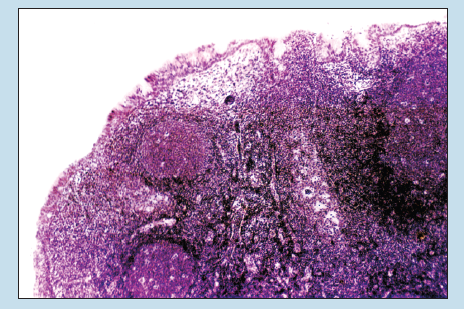

Palatine Tonsil

Figure 11-3 shows a palatine tonsil covered with a nonkeratinized, stratified squamous epithelium (mucosal type) (see section on Stratified Squamous Epithelium in Chapter 2). The stratified squamous epithelium is continuous with the free surface of the pharynx. At various locations on the surface of the tonsil, deep indentations or pockets, termed crypts (not visible on this photomicrograph), will occur. Distributed along the crypts are lymphoid nodules. Many of these nodules will possess germinal centers.

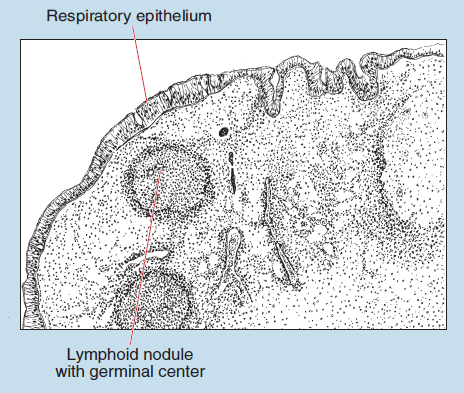

Pharyngeal Tonsil

Pharyngeal tonsils (Figure 11-4) are quite similar to palatine tonsils. However, the epithelium on the free surface is different because it is composed of a typical respiratory epithelium (pseudostratified columnar epithelium with cilia and mucous cells) (see section on Pseudostratified Ciliated Columnar Epithelium in Chapter 2). Patches of stratified squamous epithelium are sometimes found on pharyngeal tonsils of humans, more commonly on the pharyngeal tonsils of a child than on those of an adult.

Figure 11-1 (25X): Diffuse lymphoid tissue associated within a bronchus of the respiratory system.

Figure 11-2 (25X): Aggregated lymphoid nodule.

Figure 11-3 (25X): Palatine tonsil.

Figure 11-4 (25X): Pharyngeal tonsil.

Lymph Nodes

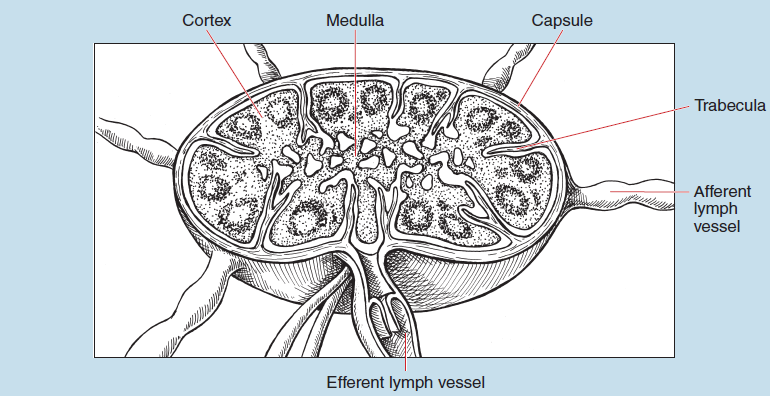

Lymph nodes are small, encapsulated lymphoid organs found along the course of lymphatic vessels throughout the body. Figure 11-5 is a line drawing of a lymph node. Use this figure to orientate yourself to the following structures of a lymph node:

- Lymph nodes are covered with a connective tissue capsule of collagenous fibers, scattered elastic fibers, and smooth muscle cells.

- At various regions of the node, the capsule extends into the body of the organ as trabeculae.

- Lymph nodes will possess several afferent lymph vessels and only one or two efferent lymph vessels.

- Lymph nodes are divided into an outer cortex and an inner medulla.

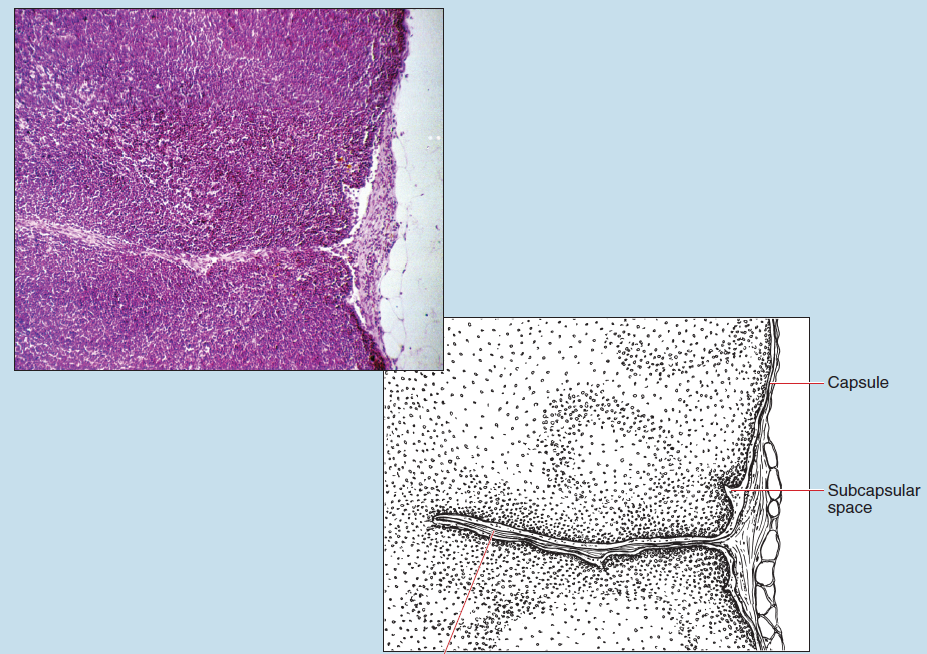

Figure 11-6 demonstrates how, at various regions of the organ, the connective tissue capsule extends into the body of the organ as trabeculae. Immediately deep to the capsule you will find the first of a series of an interconnected system of spaces, termed the subcapsular space (also called the subcapsular sinus or marginal sinus). The subcapsular space is continuous, with a space found on either side of the trabeculae, termed the paratrabecular space (also termed trabecular sinuses, intermediate sinuses or cortical sinuses), which may not be visible on your section.

Figure 11-5: Line drawing of a lymph node.

Figure 11-6 (25X): Lymph node.

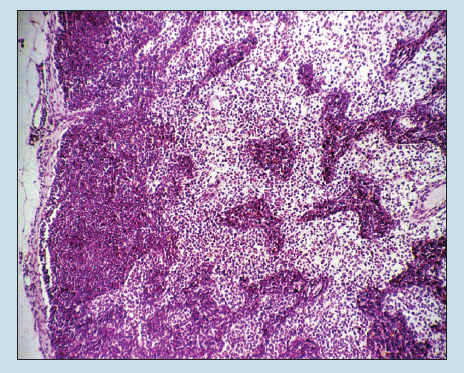

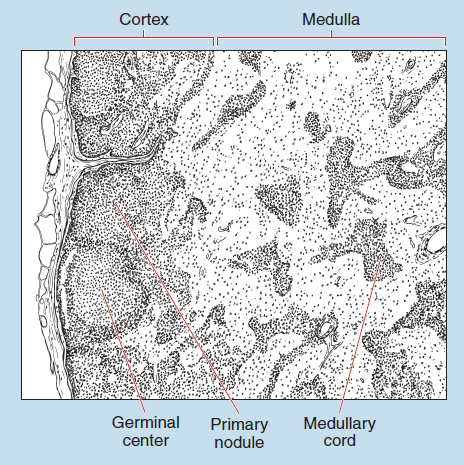

Figure 11-7 demonstrates that the trabeculae and elements of the lymphoid organ are arranged differently in the outer (cortical) and inner (medullary) regions of the organ.

In the cortex, the trabeculae are arranged more or less perpendicular to the surface. The lymphocytes of the cortex are closely packed, forming nodules. If these nodules are composed mostly of small lymphocytes, they are termed primary nodules. However, if they possess a paler central zone, called a germinal center, they are termed secondary nodules.

The deep cortex (also termed the juxtamedullary cortex or paracortex) lacks nodules, and the cells are more loosely packed than those within the more superficial cortex. Small lymphocytes are the most common cell type within the deep cortex, and large lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and macrophages are rarely seen. Figure 11-8 demonstrates the cortex of a lymph node, including primary and secondary nodules.

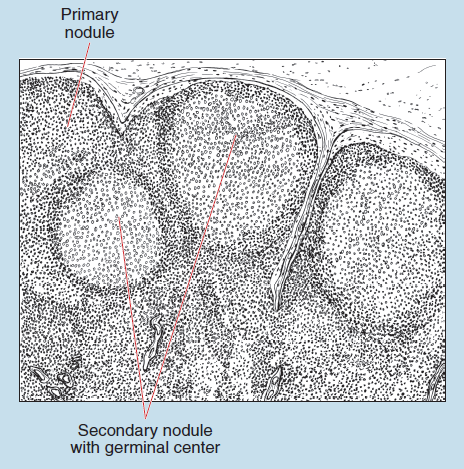

The medulla of the lymph node is composed of medullary cords surrounded by medullary sinuses. The medullary cords are aggregations of lymphoid tissue. These cords branch and anastomose freely and are not prominent in a resting lymph node. They are composed of reticular fibers, reticular cells, small lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and macrophages. Figure 11-9 demonstrates a cross-sectional view and a longitudinal view of medullary sinuses. These sinuses are surrounded by lymphocytes arranged into poorly defined medullary cords.

Reticular cells, macrophages, and endothelial cells line the medullary sinuses. Medullary sinuses, which are continuous with the subscapular and paratrabecular spaces, are lined by reticular cells and macrophages. Gaps between adjacent endothelial cells (not visible on the photomicrograph) in medullary sinuses are considerably larger than the gaps in the capillaries of the cardiovascular system.

Figure 11-7 (25X): Lymph node.

Figure 11-8 (25X): Lymph node.

Figure 11-9 (100X): Medullary sinuses of a lymph node.

Figure 11-9 (100X): Medullary sinuses of a lymph node.

Thymus

Thymus/Child

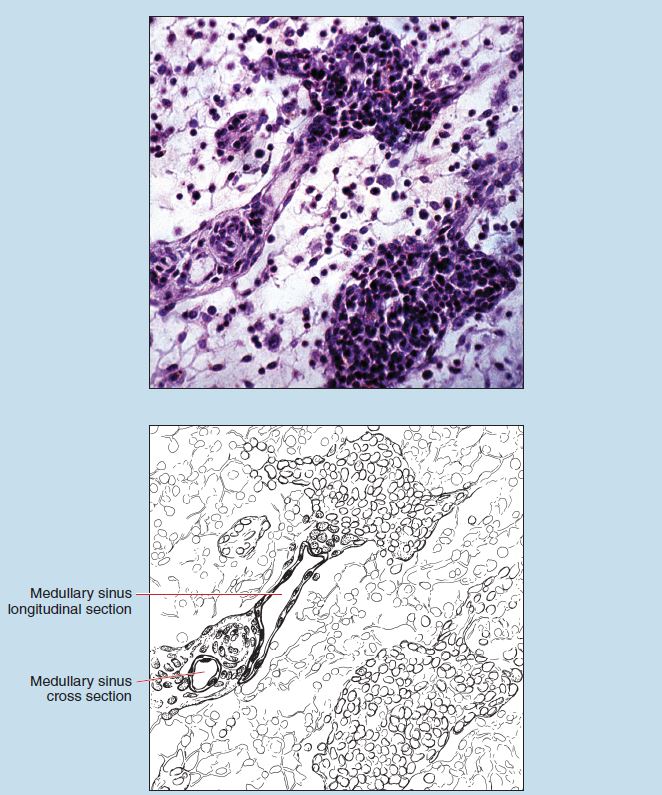

The thymus is composed of lobules joined by connective tissue and slender strands of lymphoid tissue. A capsule composed of fibroelastic connective tissue surrounds the gland. Relatively coarse trabeculae branch off of the capsule and incompletely divide the gland into lobules.

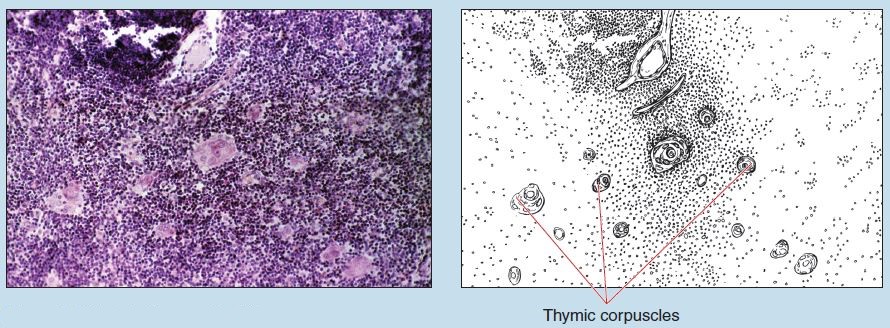

Figure 11-10 shows that each lobule of the thymus contains a cortex and medulla. The cortex of the thymus stains more basophilic as compared with the medulla. This staining differential is due to the varying cellular populations in the cortex and medulla, in that thymic lymphocytes are found in higher concentrations within the cortex as compared with the medulla.

The thymus lacks lymphoid nodules; this is a major histological feature.

Throughout the entire thymus are epithelioreticular cells (not visible in this photomicrograph), the second cell type found within the thymus. Epithelioreticular cells are actually epithelial cells joined to one another by desmosomes at the end of long, cytoplasmic processes. These epithelioreticular cells serve as a cellular framework for the thymus and histologically resemble reticular cells.

Thymic corpuscles (also termed Hassal’s corpuscles) are visible in Figures 11-10 and 11-11. These structures, which are major histological features of the thymus, are composed of concentrically arranged epithelioreticular cells. Their function is unknown.

Figure 11-10 (25X): Thymus of a child.

Figure 11-11 (50X): Thymus of a child.

Thymus/Adult (Atrophic or Involuted Thymus)

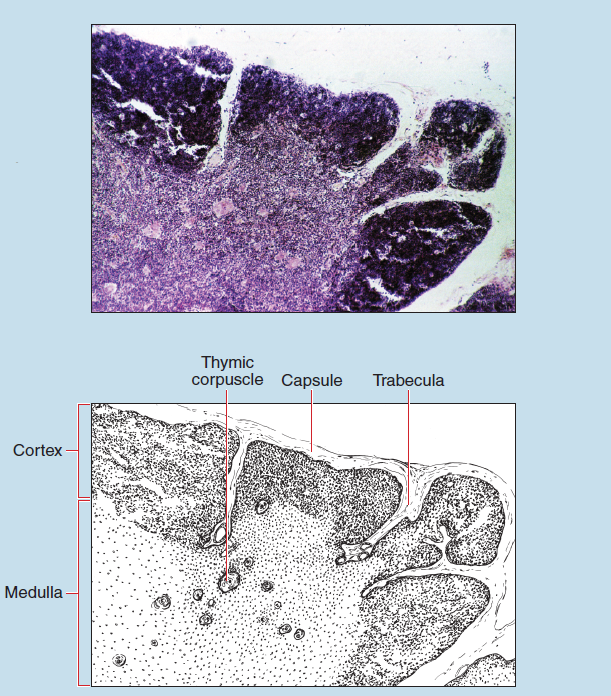

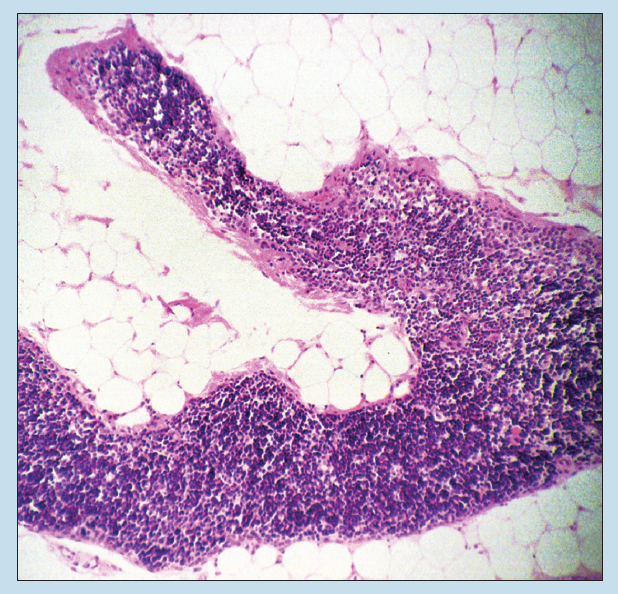

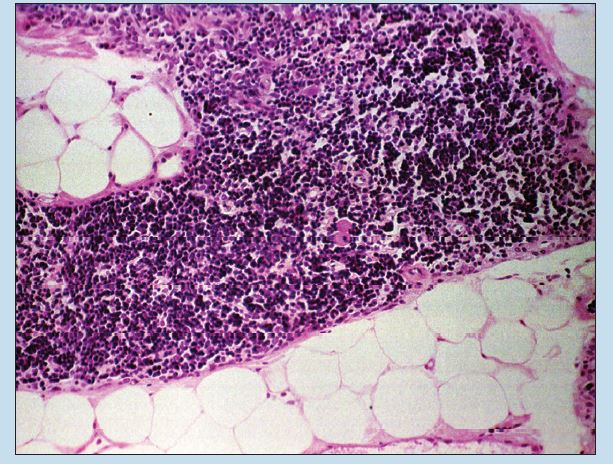

Figures 11-12 and 11-13 show an adult thymus undergoing atrophy or involution, which is believed to start at puberty. However, a relative decline in the volume of thymic parenchyma may actually begin earlier in childhood.

During the involution process, the thymus is infiltrated with adipose tissue. The clearly lobulated structure, as well as the definitive medullary and cortical structure, is lost. The number of thymic lymphocytes is reduced, and the epithelioreticular cell becomes the major cellular element. Thymic (Hassal’s) corpuscles, however, are not affected by the involution process and remain a major histological feature of the thymus, regardless of the age of the individual from whom the specimen was obtained.

Compare the features exhibited in an atrophic thymus to those of a thymus from a healthy child (see Figures 11-10 and 11-11).

Figure 11-12 (25X): Atrophic thymus.

Figure 11-13 (50X): Atrophic thymus.

Figure 11-13 (50X): Atrophic thymus.

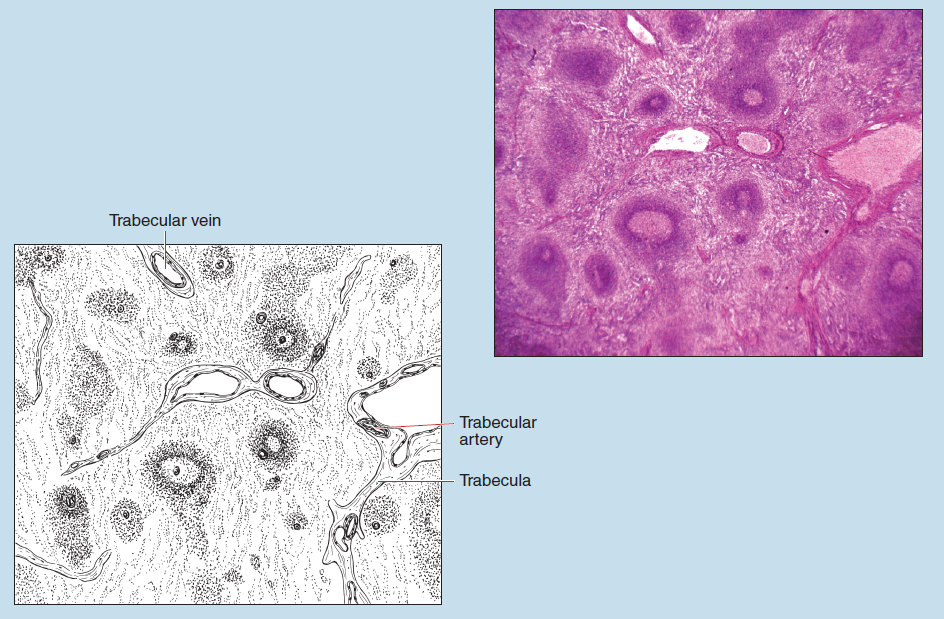

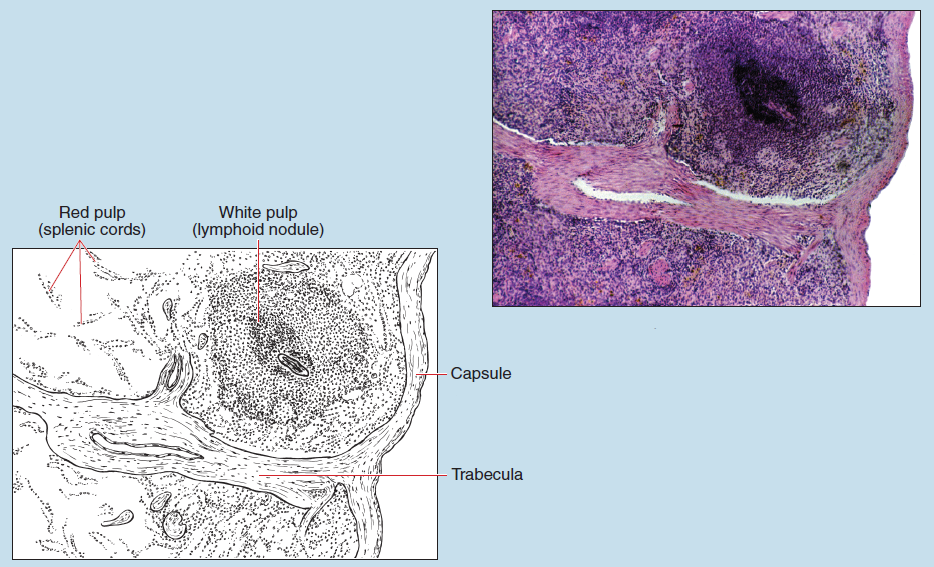

Spleen

The spleen (Figure 11-14) is covered by a fibrous capsule that possesses numerous elastic fibers and some smooth muscle. (The capsule is not visible on this photomicrograph.) Dense trabeculae extend into the spleen from the capsule. These will branch and form incomplete anastomosing chambers. Located adjacent to or within the trabeculae are trabecular arteries and trabecular veins.

The spaces between the connective tissue trabeculae are filled with soft, spongy tissue known as splenic pulp (Figure 11-15). On the basis of color differences seen in freshly dissected preparations, the pulp is subdivided into red pulp (also called splenic cords) and white pulp (also called lymphoid nodules). Red and white pulp will not stain red and white in your preparations, nor do they appear red and white in these photomicrographs. Both types of pulp are composed of lymphoid tissue.

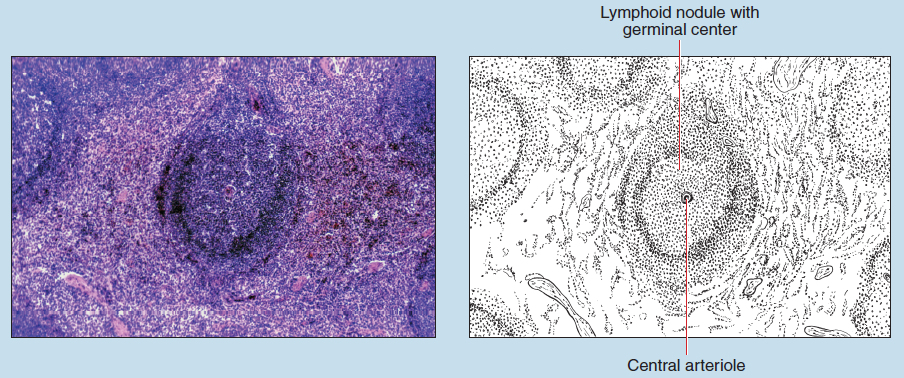

The white pulp (Figure 11-16) consists of lymphocytes. In hematoxylin and eosin sections, white pulp stains basophilic because of the presence of numerous lymphocyte nuclei. The white pulp of the spleen is aggregated into lymphoid nodules. These nodules contain germinal centers, which tend to decrease in number with increasing age. Within each germinal center is a central arteriole (previously termed a central artery) that is a continuation of the trabecular artery. This central arteriole may be centrally located within the germinal center, or it may be displaced peripherally. Regardless of its location, the presence of a central arteriole associated with a lymphoid nodule is a major histological feature of the spleen.

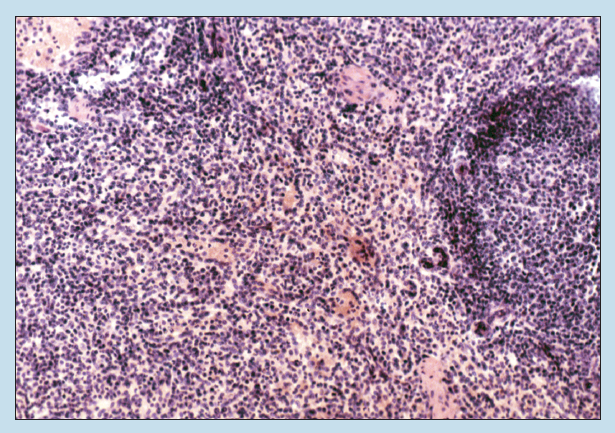

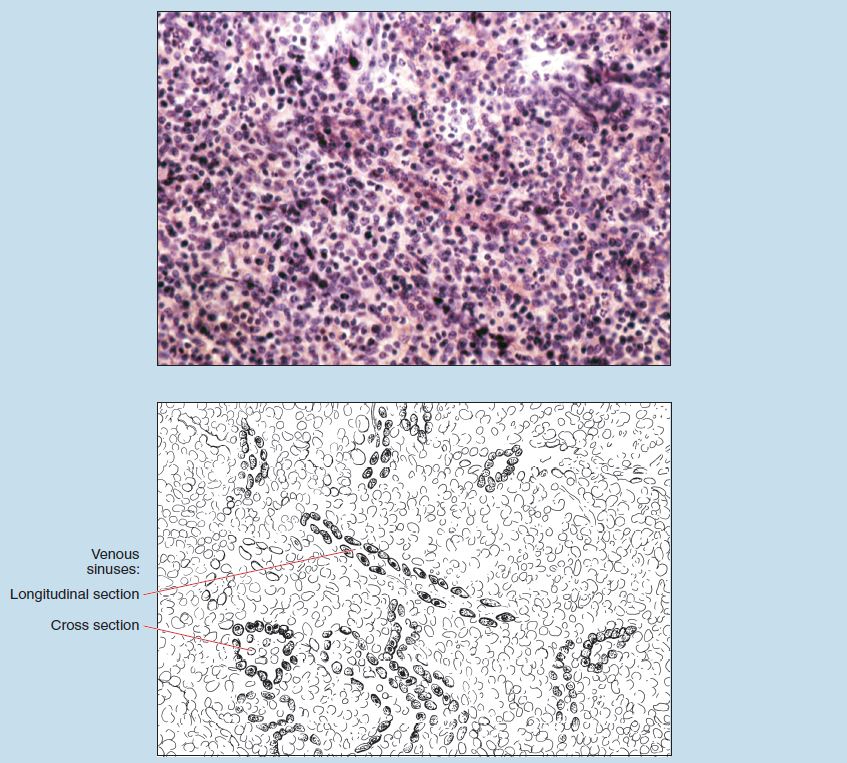

Figure 11-17 demonstrates a lymphoid nodule with a germinal center on the right side of the photomicrograph. Figure 11-18 is a high-power photomicrograph of the red pulp found adjacent to the lymphoid nodule seen in Figure 11-17.

Surrounding the white pulp is a diffuse cellular network that constitutes the red pulp of the spleen (Figures 11-17 and 11-18). The red pulp consists of venous sinuses (also termed splenic sinuses) surrounded by splenic cords (the cords of Billroth). Splenic cords consist of reticular fibers and reticular cells supporting lymphocytes, macrophages, plasmocytes, erythrocytes, and various granulocytes (see sections on Loose, Irregular Connective Tissue [Mesenteric Spread] and Loose, Irregular Connective Tissue [Lamina Propria of the Duodenum] in Chapter 3).

Endothelial cells (Figure 11-18) line the venous sinuses of the red pulp. The sinuses are extremely attenuated and orientated with their axis parallel to the longitudinal axis of the sinus. The large spaces between these endothelial cells facilitate the easy passage of erythrocytes into and out of the sinuses.

Appendix

The appendix is often classified as a lymphoid organ. However, it will be discussed in conjunction with the hollow organs of the gastrointestinal tract in Chapter 16.

Figure 11-14 (50X): Spleen.

Figure 11-15 (25X): Spleen.

Figure 11-16 (50X): Spleen.

Figure 11-17 (50X): Spleen.

Figure 11-18 (100X): Spleen.