Chapter Objectives

This chapter will enable you to:

1. Differentiate among the subclasses of connective tissue discussed in this chapter, including:

- Loose, irregular (areolar) connective tissue

- White (unilocular) and brown (multilocular) fat

- Reticular connective tissue

- Dense irregular connective tissue

- Dense regular connective tissue, including tendon and elastic (yellow) ligament

2. Identify the different cells and fiber types found in connective tissue

Connective Tissue Function and Composition

Connective tissue is subdivided into the following categories and subcategories:

- Connective Tissue Proper

- Loose connective tissue proper

- Loose, irregular (areolar) connective tissue

- White and brown fat

- Reticular connective tissue

- Dense connective tissue proper

- Irregular dense connective tissue

- Regular dense connective tissue (tendons and ligaments)

- Loose connective tissue proper

- Specialized Connective Tissue

- Cartilage

- Bone

- Blood

Functions of Connective Tissue

All forms of connective tissue perform a variety of functions, including:

- Filler and packer, in that the body has few, if any “empty” spaces within it

- Energy storage

- Ion storage

- Support

- Protection

- Attachment

- Insulation

- Serving as a diffusion medium for the transport of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nutrients

Connective tissue is composed of cells and an extracellular matrix. The extracellular matrix is, in turn, composed of a ground substance and organic connective tissue fibers that provide support and attachment. The ground substance consists of structural glycoproteins, proteoglycans, electrolytes, and other components that serve as a diffusion medium and also provide varying amounts of support. The proportions of these two components (fibers and ground substance), as well as their composition, will vary from one type of connective tissue to another. The extracellular matrix will also vary in consistency from one form of connective tissue to another. Indeed, connective tissues, with the exception of adipose tissue, are identified by the histological characteristics of the extracellular matrix.

Connective tissue, with some exceptions, generally has a rich blood supply, thereby allowing it to provide nutrients to adjacent tissues.

Loose, Irregular (Areolar) Connective Tissue

Loose, irregular connective tissue (also termed loose areolar connective tissue) derives its name from the arrangement of its intercellular fibers and the way in which they divide the extracellular matrix into small spaces (areola). The fibers of loose, irregular connective tissue are loosely and irregularly arranged, thereby making the diagnosis of cell and fiber types relatively easy.

This type of connective tissue is distributed widely throughout the body. It is found in the following anatomical locations:

- Surrounding blood vessels and nerves

- Forming superficial and deep subcutaneous fascia, mesenteries, and a portion of the supporting framework for most of the organs of the body

- Filling open spaces and cavities throughout the body

Loose, irregular connective tissue contains a varying population of fixed and wandering cells, including fibroblasts, fibrocytes, adipose cells (adipocytes or fat cells), mast cells, plasmocytes (plasma cells), and macrophages. If the number of adipose cells is high, then the tissue is appropriately named adipose tissue. Loose, irregular connective tissue will regularly contain all three possible fiber types: collagen, reticular, and elastic fibers.

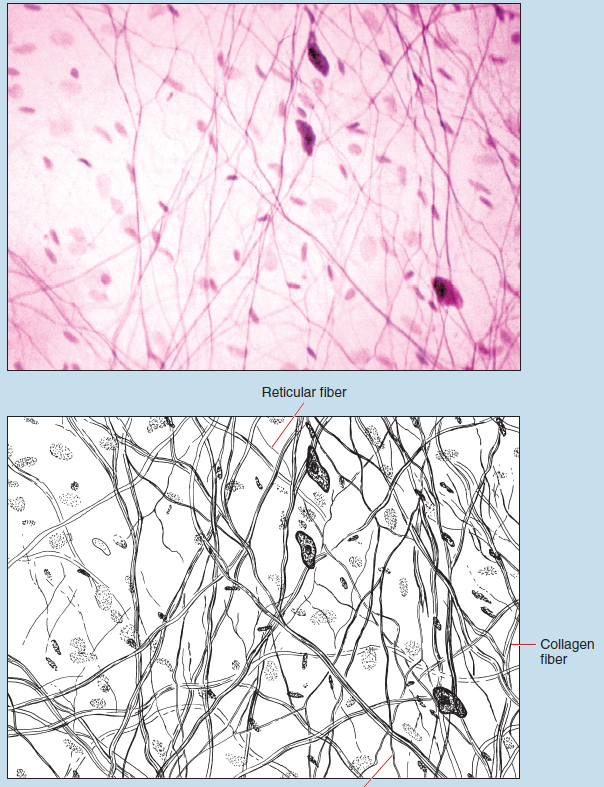

Loose, Irregular Connective Tissue (Mesenteric Spread)

Figures 3-1 and 3-2 show a mesenteric spread. The best way to identify collagen, reticular, and elastic fibers within tissue preparations is via the use of specialized stains (see Appendix). Collagen, reticular, and elastic fibers may be seen within these photomicrographs.

- Collagen fibers are the dominant fiber type within loose, irregular connective tissue. Collagen fibers appear as wide, wavy, ribbon-like bands that stain with acidic dyes, such as eosin. These fibers will have varying diameters and may appear longitudinally striated because of their fibrillar substructure.

- Elastic fibers are considerably thinner than collagenous fibers and typically appear as straight, narrow, single fibers that branch frequently. Even though elastic fibers do not typically stain in standard hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) preparations, they may be seen within these photo micrographs because of their high degree of refractive ability (refringence).

- Reticular fibers are present in varying numbers in loose, irregular connective tissue. These fibers constitute the support network of many anatomical structures. Reticular fibers are narrow bundles of collagen fibrils that are coated with glycoproteins and proteoglycans, resulting in special staining properties. Specific stains must be used to see reticular fibers, and therefore they may not be seen within H & E photomicrographs. Reticular fibers are quite fine and branch frequently because of the longitudinal splitting of the collagen bundles.

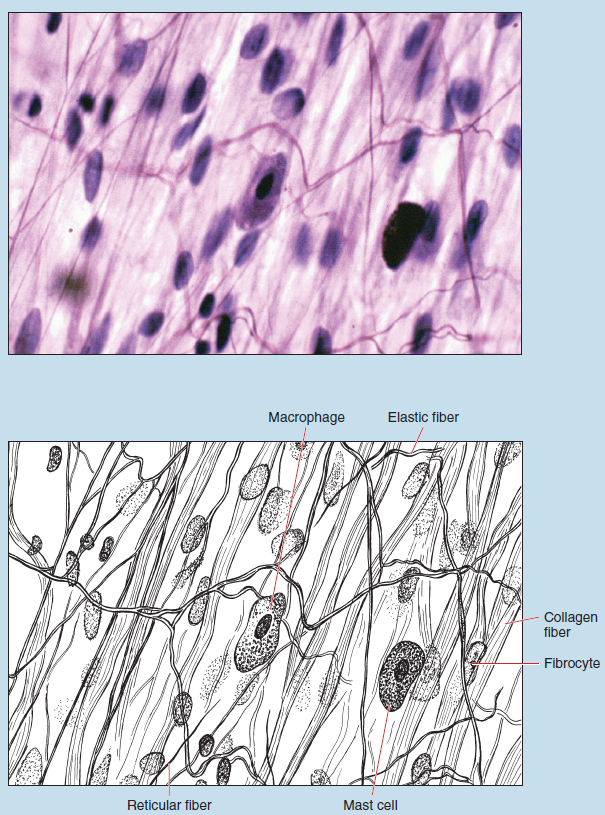

The cellular population within loose, irregular connective tissue will vary considerably from one preparation to another. This variation will depend on the immunological status of the person or animal from which the preparation was obtained. Figures 3-1 and 3-2 demonstrate fibrocytes, macrophages, and mast cells.

- Fibrocytes are the most numerous cells within loose, irregular connective tissue. They are responsible for maintaining the fibers within the extracellular matrix, as compared with fibroblasts, which secrete the connective tissue fibers. Therefore fibrocytes are minimally involved in the secretion of proteins. As a result, the cytoplasm of fibrocytes will stain clear to lightly acidophilic and will be poorly visible in H & E preparations.

- Macrophages are the second most common cell type of loose, irregular connective tissue. Macrophages are irregularly shaped cells with a rounded, dark staining nucleus. Inactive macrophages are difficult to distinguish from fibrocytes with the light microscope.

- Mast cells are some of the largest wandering cells of connective tissue. They occur in varying numbers within loose, irregular connective tissue but are especially numerous around blood vessels and deep to the epithelium of the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. Mast cells are large cells with ovoid nuclei and possess numerous cytoplasmic granules that are basophilic. However, these granules are water soluble and therefore may be difficult to see in H & E preparations.

Figure 3-1 (50X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (mesenteric spread).

Figure 3-1 (50X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (mesenteric spread).

Figure 3-2 (250X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (mesenteric spread).

Figure 3-2 (250X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (mesenteric spread).

Loose, Irregular Connective Tissue (Lamina Propria of the Duodenum)

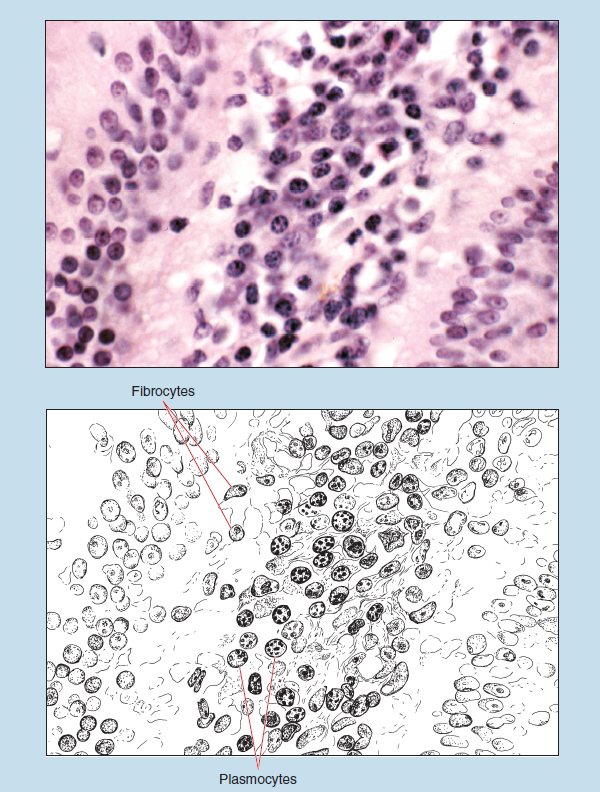

Figure 3-3 is a high-dry photomicrograph of the loose connective tissue normally found within the lamina propria of the duodenum. This layer of connective tissue is typically highly vascular and contains a varying population of fixed and wandering connective tissue cells. Figure 3-3 demonstrates a variety of connective tissue cells, including fibrocytes and plasmocytes (plasma cells).

Plasmocytes are relatively rare in loose, irregular connective tissue under normal circumstances, but their numbers increase considerably during the inflammation process. Plasmocytes are small and irregularly shaped cells, with a relatively small and eccentrically placed nucleus. The nuclear chromatin appears as deep staining granules arranged in such a way as to give the cell a “clock-faced” appearance, which is a major histological feature of this cell type.

Figure 3-3 (100X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (lamina propria of duodenum).

Figure 3-3 (100X): Loose, irregular connective tissue (lamina propria of duodenum).

Adipose Tissue

Adipose cells (adipocytes) are found singly or in groups in almost all forms of loose, irregular connective tissue. In certain anatomical locations, however, adipose cells will be found in high numbers and will be organized in such a way that the resulting tissue is designated as adipose tissue. When arranged into adipose tissue, adipose cells are regarded as fixed connective tissue cells.

Adipose tissue differs from other forms of connective tissue in that the intercellular material does not make up the bulk of the tissue. As a result, it is not used as the main histological characteristic for this tissue. In contrast, the cells and their contents are the main histological features of adipose tissue.

Adipose tissue may be subdivided into white (unilocular) and brown (multilocular) adipose tissue (fat). This subdivision is based on the color of the fat when viewed on gross dissection, as well as the method by which the cells store the fat globules.

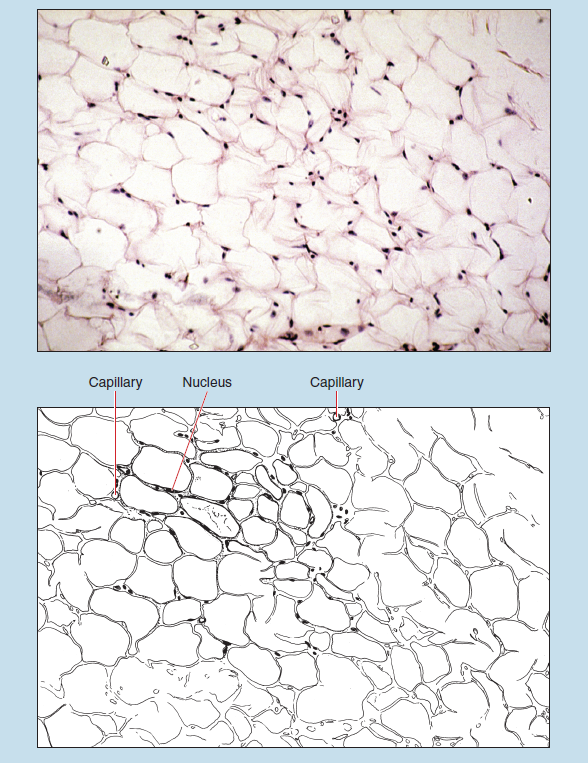

White (Unilocular) Adipose Tissue

Figure 3-4 is a photomicrograph of white (unilocular) adipose tissue taken from the connective tissue surrounding the pancreas. This photomicrograph presents typical white adipose cells (unilocular adipocytes), as well as numerous cells that were damaged during sectioning and preservation, an artifact commonly seen in such histological preparations.

The following are characteristics of adipose cells of white fat:

- Individual fat droplets fuse to form a large, single fat droplet that comes to occupy the greater proportion of the cell.

- The nucleus is forced to the periphery of the cell. The cytoplasm becomes quite attenuated and forms a thin peripheral layer within the cell. It is because of this position of the nucleus and the small amount of cytoplasm that white adipose cells are described as having a “signet ring” conformation.

- Adipose cells have a clear or hollow appearance as a result of the dissolution of the fat droplet during the histological processing, thus leaving an empty space within the cell.

Adipose tissue differs from other forms of connective tissue in that individual adipose cells are surrounded by a thin basal lamina that may or may not be visible in light microscope sections. In addition, adipose tissue is highly vascularized, and a large number of capillaries are visible within this section.

Figure 3-4 (50X): White (unilocular) adipose tissue.

Figure 3-4 (50X): White (unilocular) adipose tissue.Brown (Multilocular) Adipose Tissue

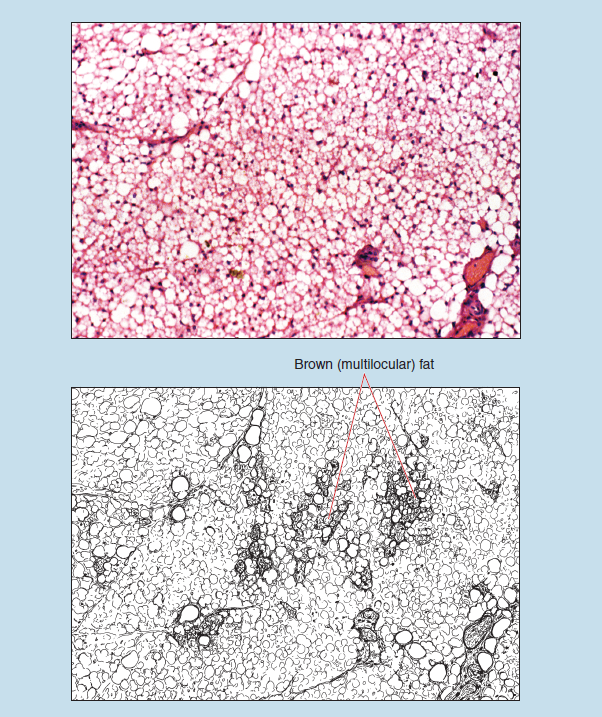

Figure 3-5 demonstrates brown (multilocular) fat intermixed with white fat. Brown fat has a widespread distribution in hibernating animals, whereas in humans it has a considerably smaller distribution. Brown fat is typically found within the interscapular and inguinal regions of humans, with the amount decreasing after birth.

Brown fat differs from white fat (Figure 3-4) in the following two ways:

- White fat stores all of the lipid droplets within one coalesced lipid droplet, whereas brown fat stores the lipid droplets within multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles—hence the multilocular appearance of brown adipose cells.

- As a result of this form of lipid storage in brown fat, the nucleus is typically centrally located within the cell and is round in shape.

Also visible within this photomicrograph are several connective tissue septa, which divide the adipose tissue into lobules. Some of the septa have blood vessels associated with them.

Figure 3-5 (50X): Brown (multilocular) adipose tissue.

Figure 3-5 (50X): Brown (multilocular) adipose tissue.

Reticular Connective Tissue

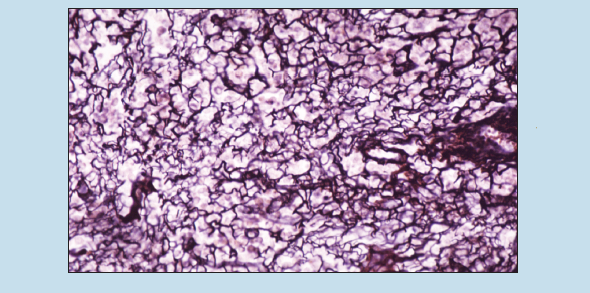

Reticular Connective Tissue (Lymph Node)

Reticular fibers are not visible in routine H & E sections. A particular stain called reticulin stain (see Appendix) must be used to see this fiber type. Reticular connective tissue forms a structural framework for many tissues and organs, including bone marrow and lymphoid organs.

In Figure 3-6, reticular fibers appear dark blue to black and obscure the underlying lymphoid cells. As you examine this photomicrograph, note that the reticular fibers may be found singly or in clumps. Single fibers have a relatively thin diameter and branch considerably.

Figure 3-6 (50X): Reticular connective tissue (lymph node).

Figure 3-6 (50X): Reticular connective tissue (lymph node).

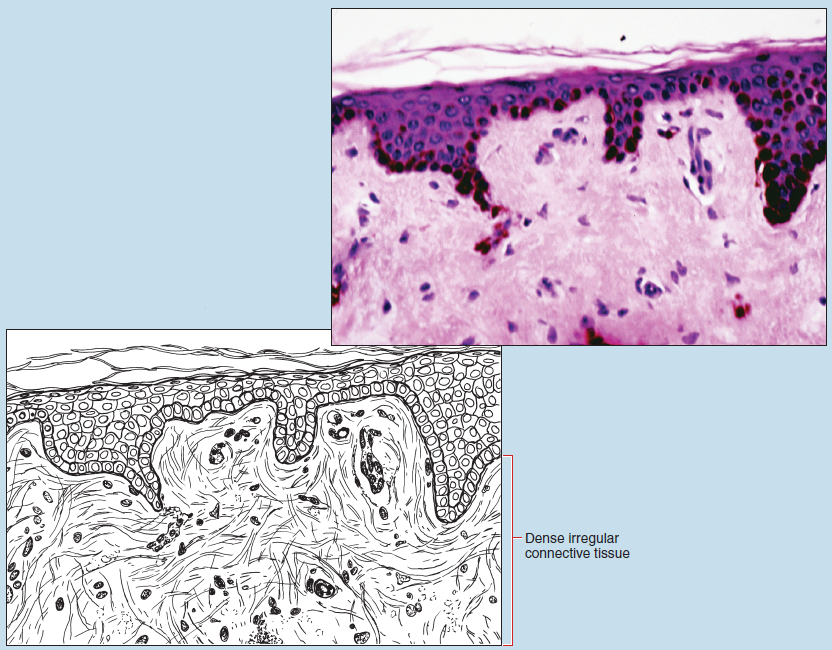

Dense Irregular Connective Tissue

Dense irregular connective tissue differs from loose, irregular connective tissue in the following ways:

- The connective tissue fibers within the extracellular matrix are more densely arranged because of the higher concentration of thick bundles of collagen fibers.

- The cells are fewer in number and type. Dense irregular connective tissue is composed mostly of fibrocytes and macrophages. White blood cells and adipose cells are typically not present in dense, irregular connective tissue.

Figure 3-7 is a photomicrograph of thin skin. Deep to the stratified squamous epithelium (see Stratified Squamous Epithelium section in Chapter 2) will be found dense, irregular connective tissue that comprises the bulk of the dermis of the skin. Collagen fibers dominate within this type of tissue, but reticular and elastic fibers may be present in varying amounts. The collagen fibers interlace considerably, forming a tough, latticelike network of fibers that may continue into adjacent tissues.

Figure 3-7 (100X): Dense irregular connective tissue (dermis of the skin).

Figure 3-7 (100X): Dense irregular connective tissue (dermis of the skin).

Dense Regular Connective Tissue

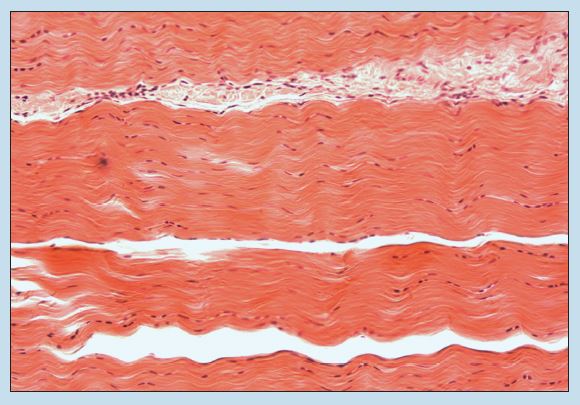

Tendons, aponeuroses, and ligaments are the most common examples of structures composed of dense regular connective tissue. Connective tissue fibers are arranged in a parallel fashion within this tissue, thereby giving the structures significant tensile strength.

Tendon

The histological identification of tendons and elastic (yellow) ligaments is quite difficult, but with adequate practice and side-by-side comparisons it can be readily accomplished.

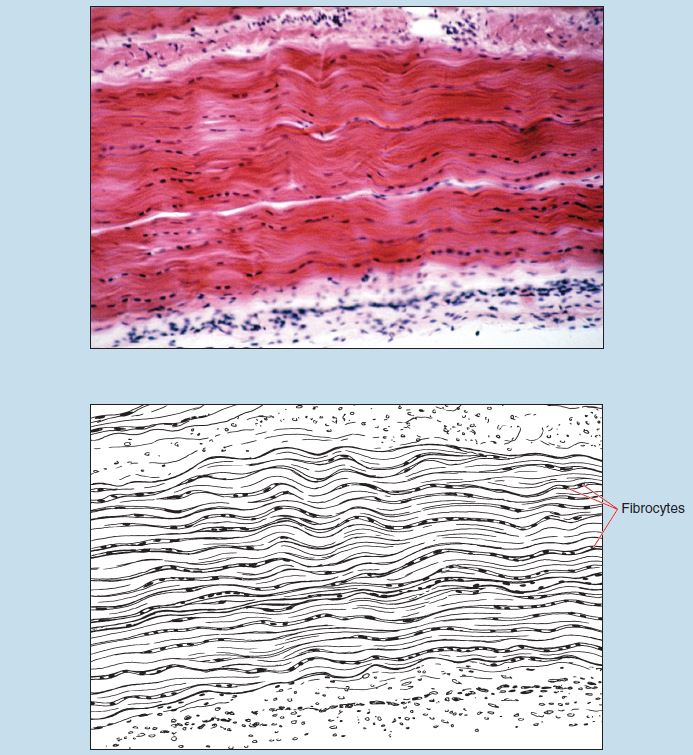

Figures 3-8 and 3-9 are longitudinal H & E sections of a tendon. Tendons demonstrate collagen fibers that are closely packed and parallel and that appear quite homogenous. Because of the fixation process, these fibers are frequently wavy in appearance. In addition, because such preparations often vary in thickness within the field of vision, staining intensity may vary considerably, with the preparation being lighter in some sections of the field of vision and darker in others. Such fixation and staining artifacts are quite common in this tissue and are evident in Figure 3-8.

Fibrocytes are the only cell type found within this form of connective tissue and are to be found lying between the fiber bundles. These cells are typically elongated in appearance and have prominent nuclei. The location of the fibrocytes, their shape, and the manner in which they appear to be “regularly arranged” between the fiber bundles is a major histological feature of tendons.

Figure 3-8 (35X): Tendon (dense regular connective tissue).

Figure 3-9 (50X): Tendon (dense regular connective tissue).

Elastic Ligament

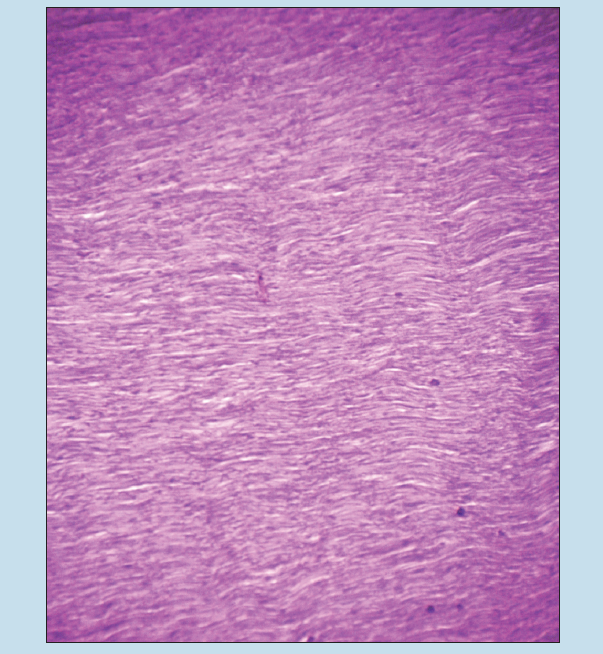

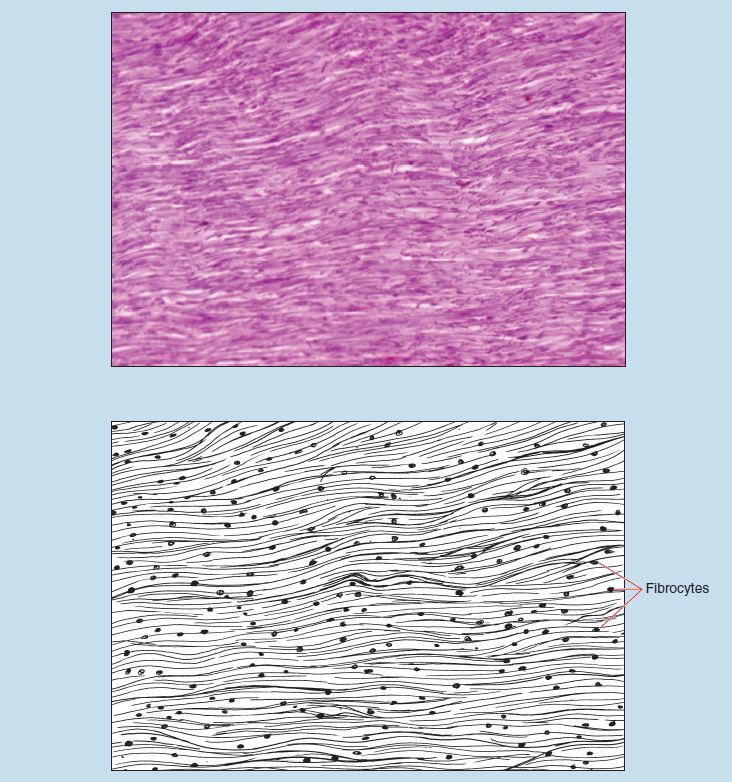

Collagenous ligaments are quite similar to tendons in composition and histological appearance because they are composed of a mixture of collagen and elastic fibers. Other ligaments, such as elastic ligaments (yellow ligaments), may be composed entirely of elastic fibers. As with tendons, fixation and staining artifacts may be quite common in ligament preparations.

Figures 3-10 and 3-11 are photomicrographs of an elastic ligament. Note that the elastic fibers appear as structureless, homogenous threads that branch and anastomose frequently. The fibers are dense and approximately parallel.

Fibrocytes are the only cell type present within ligaments; they do not appear as elongated as the fibrocytes seen in tendons (Figures 3-8 and 3-9). Ligaments (particularly elastic ligaments) may be distinguished from tendons in that fibrocytes nuclei are not found between the fiber bundles. Rather, the fibrocyte nuclei are found among the individual fibers. Because of this, the arrangement of the fibrocytes in an elastic ligament appears more random in comparison with that seen in tendons.

Figure 3-10 (25X): Ligament (elastic type) (dense regular connective tissue).

Figure 3-10 (25X): Ligament (elastic type) (dense regular connective tissue).

Figure 3-11 (50X): Ligament (elastic type) (dense regular connective tissue).

Commonly Misidentified Tissues

Dense Regular Connective Tissue: Tendon and Elastic Ligaments

Tendons and ligaments are examples of dense regular connective tissue. Both are characterized by the close packing of connective tissue fibers, and both occur in the form of sheets, bands, and cordlike structures. In addition, fibrocytes are the only cell type found in both of these structures. These similarities, as well as common changes that occur during fixation, make the differentiation between tendon and ligament quite difficult.

Tendon (Review Figures 3-8 and 3-9 in Tendon section)

- Fibrocytes are relatively few in number.

- Fibrocytes are found between the bundles.

- Fibrocytes tend to be elongated in shape.

Ligament (Elastic Type) (Review Figures 3-10 and 3-11 in Elastic Ligament section)

- Fibrocytes appear more numerous than in tendons.

- Fibrocytes are found among the bundles of fibers

- Fibrocytes tend to be less elongated.

White and brown fat are considered to be a form of specialized connective tissue by some histologists.