14.3 Transportation Modes

Building on our previous discussion on the strategic aspects of transportation modes, this section delves into the operational aspects of different modes of transport. We will explore surface transport (trucking and rail), international transportation (ocean and air), and pipelines.

14.3.1 Trucking

In 2022, the trucking industry was responsible for moving over 11.4 billion tons of freight, generating more than $940 billion in revenue. This mode of transportation played a pivotal role in international trade, particularly in North America, where trucks transported 61.9% of the value of surface trade between the U.S. and Canada and 83.5% with Mexico, totaling $947.92 billion worth of goods. In Europe, the road freight market size reached 324.5 billion euros in 2020.

Trucking is not a monolithic industry but is segmented into various categories. These can be broadly defined as Parcel, Less than Truckload (LTL), and Full Truckload (FTL):

- Parcel: Involves the transportation of small, individual packages. This segment is often characterized by a high volume of shipments and is dominated by companies that specialize in parcel delivery.

- Less than Truckload (LTL): This category includes shipments that are larger than parcel but do not fill an entire truck. LTL carriers typically consolidate freight from multiple shippers into a single truckload.

- Full Truckload (FTL): As the name suggests, FTL shipments occupy the full capacity of a truck. This segment is ideal for large shipments that need to be transported over long distances.

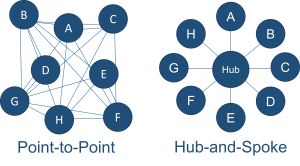

Each of these trucking segments operates within distinct network structures, influencing their cost and efficiency. The two primary models are the hub-and-spoke network, commonly used in parcel and LTL (Less than Truckload) services, and the point-to-point network, typically employed for FTL (Full Truckload) shipments.

Hub-and-Spoke Network:

In the hub-and-spoke model, shipments are first transported to a central hub, which acts as a sorting and consolidation center. This model is particularly effective for parcel and LTL services, where numerous small shipments from various origins are aggregated. At the hub, these shipments are sorted according to their destinations and then dispatched accordingly. This structure allows for significant economies of scale by consolidating shipments, leading to reduced transportation costs. However, it may result in longer delivery times due to the additional handling and detour through the hub.

Point-to-Point Network:

Conversely, the point-to-point network entails direct transportation from the shipment’s origin to its destination, bypassing any intermediate hubs. This approach is most efficient for FTL shipments, where an entire truck is filled with goods from a single origin heading to a single destination. The absence of intermediate stops for sorting or consolidation makes this network faster than the hub-and-spoke model, offering quicker delivery times. While it eliminates the need for additional handling, it may not be as cost-effective for smaller loads due to the lack of consolidation benefits.

In summary, while the hub-and-spoke network is optimized for managing a large volume of small, diverse shipments, the point-to-point network is tailored for larger, uniform shipments requiring direct transit. These network structures significantly influence the operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness of trucking services.

Interestingly, the cost of trucking does not increase linearly with distance. For example, if the distance doubles, the increase in freight charges is less than double. This is due to the fixed costs associated with each shipment, such as loading and unloading, which do not change significantly with distance. This principle generally applies to all modes of transportation.

14.3.2 Rail Transport

Rail transport is a significant contributor to both the U.S. and European economies. In the U.S., the rail industry adds over $250 billion annually and supports more than 1.1 million jobs. Railroads move over 1.4 trillion ton-miles of freight each year, more than any other mode in the country. The European rail industry is similarly impactful, contributing over €400 billion to the economy and supporting over 2.5 million jobs.

Rail transport is a highly efficient and reliable mode of surface transport, though it is limited by the necessity for rail connections at both the source and destination. It is more environmentally friendly than road transport, using less fuel per ton of material moved, and is generally cheaper and more reliable.

However, rail transport often involves multiple loadings and unloadings of goods. For instance, goods are loaded onto a road vehicle and transported to the source rail yard, where they are then transferred to a train. This process is repeated at the destination. Due to the costs and risks associated with these multiple handlings, rail transport is typically preferred for longer distances where its cost and efficiency advantages can be fully realized.

14.3.3 Ocean Freight

Ocean freight is a cornerstone of global trade, commanding more than 99% of the world’s total tonnage in goods shipped. Its dominance is rooted in its capacity to transport large volumes over long distances efficiently and cost-effectively. The types of vessels used in ocean freight are specialized for different kinds of materials, each designed to optimize the transport of specific goods.

- Bulk Vessels: Bulk vessels are designed to carry dry, unpackaged goods such as cement, iron ore, and grains. These goods are loaded directly into the ship’s hold, and unloading is typically done using conveyors and pumps. The design and structure of bulk vessels are optimized for the efficient and safe transport of these materials in large quantities.

- General Cargo Vessels: General cargo vessels handle packaged merchandise. This category includes a specialized sub-type: container ships. Container ships are equipped to carry goods that are packaged in standard-sized shipping containers, facilitating easy handling and efficient space utilization. The containers used on these ships have standardized dimensions, with the most common sizes being 20 feet and 40 feet in length. The shipping load and capacity are measured in terms of Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEUs). For instance, a 20-foot container equals 1 TEU, while a 40-foot container equals 2 TEUs. Therefore, a shipment comprising 5 twenty-foot containers and 3 forty-foot containers would total 11 TEUs (5 + 3*2).

- Tankers: Tankers are ships specially designed for transporting liquids or gases, such as chemicals, petroleum, and liquefied natural gas. These vessels are equipped with specialized tanks and safety features to handle the unique requirements and risks associated with transporting these types of cargo.

- Inland Waterways: Inland waterways, encompassing rivers, canals, and lakes, form a crucial link in the global logistics network, supplementing ocean freight. These waterways are particularly effective for transporting bulk commodities and oversized cargo over shorter distances or to areas not accessible by sea. The Mississippi River system in the United States, for example, is a vital conduit for agricultural and industrial products, exemplifying the importance of inland waterways in national and regional trade. While inherently more sustainable and often more economical than road transport, inland waterways transport is subject to geographical constraints and seasonal water level variations, requiring careful planning and integration with other transport modes for effective supply chain management.

14.3.4 Air Freight

Air freight, while often significantly more expensive than ocean cargo — sometimes up to ten times more — offers unique advantages that make it an ideal choice for certain types of cargo.

Key Advantages of Air Freight:

- Speed: The most significant advantage of air freight is its speed. This is particularly beneficial for perishable goods or items with high inventory holding or stock-out costs. The rapid transit time of air freight means goods can be moved across vast distances in a fraction of the time it would take by sea, reducing the need for extensive warehousing and enabling just-in-time delivery models.

- Security: Air freight also offers enhanced security. The shorter lead times and the controlled nature of airport operations contribute to a lower risk of theft and damage. This high-security environment is crucial for valuable or sensitive items.

- Temperature Control: For cargo that requires strict temperature regulation, air freight provides an advantage. The shorter duration of air journeys allows for more precise control of environmental conditions, reducing the risk of spoilage or damage due to temperature fluctuations.

Types of Air Freight: Air freight primarily utilizes two methods of transportation: the cargo hold (or belly) of passenger aircraft and dedicated cargo freighters.

- Passenger Aircraft Belly: Many commercial flights carry cargo in addition to passengers’ luggage. This space is particularly valuable for shipping goods due to its widespread availability and frequency of flights.

- Dedicated Freighters: Dedicated cargo planes are used exclusively for transporting goods. These aircraft are designed to handle larger or irregularly shaped cargo that might not fit in the belly of a passenger plane, offering more flexibility in terms of cargo size and weight.

14.3.5 Pipelines

Pipelines represent a unique and specialized mode of transportation, primarily used for the continuous flow of liquids and gases such as oil, natural gas, and chemicals. This mode of transport is integral to the energy sector and plays a vital role in the global supply chain.

Advantages of Pipeline Transportation:

- Continuity and Efficiency: Pipelines provide a continuous flow of materials, making them highly efficient for transporting large volumes over long distances.

- Safety and Reliability: They are generally safer and more reliable than other modes of transport, especially for hazardous materials, as they reduce the risk of spills and accidents during transit.

- Cost-Effectiveness: For long-term operations, pipelines can be more cost-effective compared to other modes of transport due to lower operational costs and minimal maintenance requirements.

Disadvantages of Pipeline Transportation:

- High Initial Investment: The construction of pipelines requires a significant initial investment, making them less flexible and more capital-intensive than other modes of transport.

- Geographical Limitations: Pipelines are limited to fixed routes and require a substantial infrastructure network, limiting their flexibility to adapt to changing supply chain needs.

- Environmental Concerns: Pipeline leaks or ruptures can have severe environmental impacts, and their construction can disrupt local ecosystems.

The key to effective logistics planning lies in understanding these options and their operational nuances. Whether it’s the extensive use of trucking and rail for surface transport, the global scale of ocean freight, the rapid delivery capability of air freight, or the specialized nature of pipelines, the choice of transportation mode should be a strategic decision. This decision should consider the nature of the goods, cost factors, speed requirements, and logistical challenges specific to each mode. The insights provided here aim to guide you in selecting the most appropriate mode of transport, ensuring that your logistical strategy is efficient, cost-effective, and aligned with your broader business objectives.