5 THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

At the beginning of the 16th century, India was fragmented into various autonomous or semi-autonomous territories. The first steps toward unification were taken by Babur (1483-1530), who established the Mughal Empire in 1526. Babur’s father ruled a small Central Asian state called Fergana, now part of Uzbekistan, and was a descendant of Timur, the renowned conqueror. At the age of eleven, Babur succeeded his father as the ruler of Fergana after his father’s sudden death. Determined to reclaim the territories once controlled by Timur, Babur made a decisive move in 1504. Accompanied only by his family and a small contingent of two hundred men, he conquered Kabul in present-day Afghanistan. In 1526, leveraging the tactics and artillery he had learned from previous alliances with the Persians, Babur defeated the larger army of the Delhi Sultanate in northern India, marking the foundation of the Mughal Empire. Under his rule, northern India experienced a period of peace and prosperity, with significant advancements in agriculture through land reclamation, irrigation projects, and the introduction of new crops such as indigo, sugar cane, cotton, and mulberry trees. Babur also left behind a notable autobiography that guided his successors. By the time of his death in 1530, his empire extended from Kabul to the borders of Bihar in northeastern India.

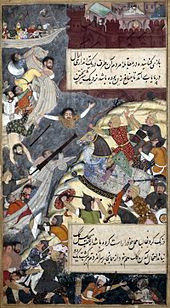

A painting of Babur crossing the Indus River, 1589. (Source: Wikimedia)

| Click and Explore |

|

Explore the Memoirs of Babur which he began to write in 1494 and continued writing until his death. |

Following Babur’s death, his son Humayun ascended the throne. After Humayun’s death, Babur’s grandson Akbar (1542-1605) succeeded him and became one of the most illustrious Mughal rulers. During his fifty-year reign, Akbar displayed exceptional leadership skills, a deep appreciation for learning and the arts, and a commitment to inclusivity, despite his probable dyslexia. He adeptly managed the religious diversity within his empire, where the ruling elite were Muslim, and the majority of the population were Hindu. Akbar sought to foster peace and harmony between Muslims and Hindus by avoiding the imposition of Islamic customs and religion on his subjects. In 1568, he abolished the jizya tax on non-Muslims, permitted the construction of new Hindu temples, and supported their maintenance financially.

Akbar integrated both Hindus and Muslims into his administration and military, reflecting his commitment to inclusivity. To strengthen his control over India, Akbar married daughters and sisters of local rulers from both Muslim and Hindu backgrounds, ensuring that these unions included elements of both traditions. Although Akbar introduced the practice of secluding royal women in a harem, which influenced both Mughal and Hindu elites, women still played significant roles in political decisions. Akbar also reformed the administrative structure of his empire, dividing it into provinces each managed by a governor, chief judge, military commander, and financial administrator. He appointed civil servants known as mansabdars, whose promotions were based on merit, and held responsibility for recruiting cavalry for the Mughal army. Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance extended to building a House of Worship in Delhi, where representatives of various religions—including Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, Jews, Jains, and Zoroastrians—engaged in interfaith discussions.

During Akbar’s reign, India experienced significant prosperity. His military campaigns unified much of the subcontinent, establishing a period of relative peace. This stability facilitated a surge in domestic and international trade, with India exporting textiles, spices, and precious gems in exchange for gold and silver. As a result, handicraft industries thrived, and merchants accumulated wealth. Although peasants bore a heavy tax burden to support the empire’s bureaucracy, they received exemptions during times of drought or natural disasters.

Among the beneficiaries of Akbar’s prosperous reign were affluent Mughal women, who invested revenues from their landed estates, imperial gifts, and inheritances in commercial ventures. They utilized their profits to fund various endeavors, including the endowment of mosques, construction of traveler’s shelters, patronage of artists and poets, and support for charitable causes. Additionally, these women used their wealth to present gifts to the emperor and court officials, attempting to exert influence over Mughal governance through strategic gift-giving.

A painting of Akbar by Govardhan, 1630 (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch a Khan Academy video explaining the history of the Mughal Empire.

|

In the late 15th century, a new religion emerged in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, which continued to grow in the 16th century. Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469-1539), the founder of Sikhism, merged the teachings of Islam and Hinduism to articulate the fundamental beliefs and practices of this religion. He famously proclaimed, “There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim,” emphasizing the unity of all religions and the shared humanity that transcends cultural and belief systems. Guru Nanak Dev Ji taught that all peoples worship the same deity and that therefore all religions are equally valid. He advocated for a virtuous life, emphasizing devotion to one God, truthful living, and service to humanity.

Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s teachings and leadership exemplify the power of persuasion, as he successfully brought together people from different religious backgrounds and convinced them to adopt a new faith that emphasized unity and shared values. His ability to persuade others was rooted in his charismatic personality, his emphasis on the universal values of truth and service, and his willingness to challenge existing religious hierarchies.

The Golden Temple, located in Amritsar, became Sikhism’s most sacred site, housing the Holy Book, the Guru Granth Sahib. The temple’s construction was initiated by Guru Ram Das, the fourth Sikh Guru, and completed by Guru Arjan Dev, the fifth Sikh Guru, in 1604. The Golden Temple symbolized the spiritual and cultural center of Sikhism, representing the faith’s emphasis on devotion, community, and service. Throughout history, the Golden Temple has remained a powerful symbol of Sikh identity and a testament to the enduring legacy of Guru Nanak Dev Ji’s teachings.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch this short video produced by the Khan Academy to learn more about the history and beliefs of the Sikhs.

|

Gujarat’s ports were characterized by remarkable diversity, with Hindus forming the majority of the population, alongside significant numbers of other religious communities. These communities were primarily trade diaspora groups, established by foreign merchants who settled and intermarried with the local population. The most notable trade diaspora communities in Gujarat were those founded by Muslims, who arrived through various channels, including Sufi mystics in the eleventh century and soldiers in the armies of central Asian and Afghan invaders from the tenth to thirteenth centuries.

Additionally, Gujarat was home to substantial numbers of Parsis, Zoroastrians whose ancestors migrated from Persia in the seventh century, likely fleeing religious persecution or settling in India before the Islamic conquest. Jews and Nestorian Christians, who split from the larger Christian Church in the fifth century, were also present, primarily from Syria and Persia. Furthermore, small communities of Indian Jains and Buddhists lived in Gujarat, contributing to the region’s religious and ethnic tapestry.

This diversity greatly contributed to Gujarat’s commercial success, as merchants traded more easily with others sharing their religion and ethnicity worldwide. Arabs traded with Arabs, Persians with Persians, and Jews maintained ties with Jewish communities across India, North Africa, and the Middle East. The prominence of Muslim merchants in Gujarat was undoubtedly aided by the Mughal emperors’ Muslim faith.

In the southern Indian subcontinent, the Vijayanagara Empire, under King Krishna Deva Raya (1471-1529), continued to prosper in the Deccan plateau region. The economy thrived, with gold coins serving as the primary currency, alongside silver, copper, and seashells. A significant textile industry developed in Gujarat, driving economic growth. During this period, Buddhism declined, and a form of Hinduism revering Vishnu became the dominant faith.

A painting of Vishnu (Source: Wikimedia)