37 THE MIDDLE EAST

The 19th century was a period of significant transformation in the Middle East, shaped by both internal developments and external pressures. The Ottoman Empire, the dominant regional power, was in a state of decline, but attempted to modernize through reforms like the Tanzimat (1839-1876) to preserve its authority. The Arab Renaissance (Al-Nahda) spurred a cultural and intellectual revival, while figures like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani advocated for pan-Islamic unity in response to growing European imperialism. Leaders such as Muhammad Ali Pasha in Egypt and the Qajar dynasty in Iran sought to modernize their states through military, economic, and administrative reforms. Meanwhile, European powers, particularly Britain and France, expanded their colonial ambitions, redrawing regional boundaries and disrupting traditional trade networks. While Middle Eastern peoples—Arabs, Turks, Persians, and others—strove to shape their own futures, imperial pressures increasingly curtailed their autonomy, setting the stage for the region’s complex struggles in the 20th century.

ARABIA AND JORDAN

The 19th century was a pivotal era for Arabia and Jordan, marked by nationalist movements, imperial interventions, and regional rivalries. In Arabia, the Wahhabi movement gained momentum, fueling opposition to Ottoman imperialism. The alliance between Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab and the founder of the current Saudi ruling family in 1744 laid the groundwork for the first Saudi state. However, this initial state was short-lived, conquered by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt in 1818, sparking a period of turmoil.

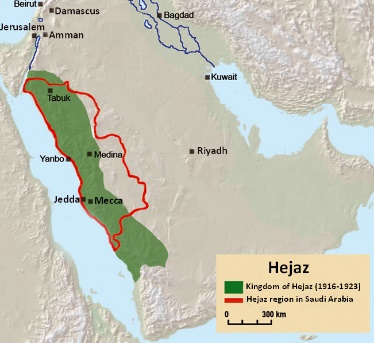

A second, smaller Saudi state emerged in 1824 in Nejd, but faced persistent challenges from the Al Rashid family throughout the century. By 1891, the Al Rashid had gained control, forcing the Al Saud into exile in Kuwait. Nevertheless, Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud recaptured Riyadh in 1902, establishing a third Saudi state. Meanwhile, Hejaz oscillated between Egyptian and Ottoman control, Bahrain maintained independence, and Aden was annexed by the British.

A map of Saudi Arabia shows the Kingdom of Hejaz (Source: Wikimedia)

Daily life in 19th-century Arabia was deeply intertwined with Islam, culture, and the harsh desert environment. The majority adhered to Islam, shaping daily routines, social structures, and community interactions. Gender roles were distinctly defined, with men as breadwinners and women managing households and child-rearing. However, women played vital roles in trade and agriculture alongside their male relatives. Family life was central to social organization, with extended families living in close-knit communities offering support and security. Occupations varied, with pastoralism, farming, and trade being common. Seasonal pilgrimages to Mecca held religious and economic significance. Trade routes facilitated commerce, enabling local merchants to exchange goods with neighboring regions. Despite challenges, the resilience and adaptability of ordinary people fostered rich cultural traditions.

In Jordan, Ottoman imperial rule persisted throughout the 19th century, minimizing Western influence. Ancient architecture preserved the region’s rich history, showcasing ingenuity. Ottoman styles dominated architecture, with limited Western artistic influences. As the century closed, the stage was set for significant changes. The Al Saud’s consolidation of power, Ottoman decline, and European colonial ambitions would profoundly shape the region’s 20th-century trajectory, influencing contemporary dynamics in Arabia and Jordan.

MEDITERRANEAN COASTAL AREAS

The 19th century marked the beginning of a new era of colonization in Palestine, with European powers increasingly exerting their influence over the region from around 1870. Meanwhile, Lebanon, although under Ottoman control, enjoyed a degree of autonomy, allowing powerful local families to rise to prominence and shape the region’s politics. The country’s mountainous regions were home to the Druze community, a unique blend of Gnosticism, Islam, and Neoplatonism. Historically, the Druze had coexisted peacefully with their Christian Maronite neighbors, but tensions began to escalate in the mid-19th century.

The simmering tensions culminated in a devastating civil war in 1860, which, although rooted in political disputes, carried significant religious undertones. The conflict resulted in the brutal slaughter of over 10,000 Maronites in cities such as Damascus, Zahlé, Deir al-Qamar, and Hasbaya. The Ottoman troops’ refusal to intervene sparked international outcry, prompting France to step in and halt the massacre. In the aftermath, the Ottoman Empire acquiesced to European pressure, agreeing on August 3, 1860, to permit 12,000 European soldiers to restore order in Lebanon. This intervention marked a significant turning point in the region’s history, underscoring the complex interplay between local politics, regional identity, and European colonial ambitions that would shape the Middle East for centuries to come.

IRAQ AND SYRIA

Throughout the 19th century, Iraq and Syria remained vital components of the Ottoman Empire, playing crucial roles in its economic, cultural, and strategic interests. However, this period also saw significant challenges to Ottoman control, particularly from neighboring Egypt. In 1832 and 1833, Ibrahim Pasha, the ambitious son of Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Egyptian viceroy, launched successful military campaigns against the Ottomans, temporarily seizing control of Syria. These conquests were part of a broader Egyptian expansionist agenda, reflecting Muhammad Ali’s vision of establishing a unified Arab state under Egyptian leadership.

Despite his initial successes, Ibrahim Pasha’s occupation of Syria proved short-lived. Pressure from European powers, particularly Britain, which sought to maintain the balance of power in the region, compelled Ibrahim to withdraw from Syria in 1840. The Ottoman Empire, though weakened, managed to reassert its control over the region. In the wake of Ibrahim’s withdrawal, the Ottomans embarked on a period of rebuilding and reform, implementing measures to strengthen their administration and modernize their military. Meanwhile, Syria and Iraq experienced significant social and economic transformations driven by trade growth, urbanization, and the emergence of new social classes. As the century progressed, the complex web of alliances, rivalries, and imperial ambitions set the stage for the dramatic changes that unfolded in the 20th century.

For ordinary people in Syria and Iraq, life under Ottoman rule in the 19th century was marked by a mix of tradition, hardship, and gradual modernization. Most people lived in rural villages or small towns, engaged in agriculture, herding, or small-scale trade. Daily life was governed by Islamic customs and social hierarchies, with family and tribe playing central roles. However, Ottoman taxation, corruption, and conscription often weighed heavily on communities. Peasants struggled with land ownership and debt, while urban artisans and merchants faced competition from European imports. Christians and Jews, who comprised significant minorities in the region – approximately 20% of Syria’s population was Christian, and 5% of Iraq’s was Jewish – generally enjoyed a degree of tolerance and protection under Ottoman rule, known as dhimmi status. This allowed them to practice their faiths and manage their internal affairs, but also imposed limitations, such as higher taxes and restricted social mobility. However, as Ottoman power waned, sectarian tensions rose, and Christians faced increasing pressure, particularly in rural areas. The 1840 Damascus Affair, in which false accusations of ritual murder sparked anti-Jewish violence, highlighted the fragility of interfaith relations. Despite these challenges, the region’s diverse communities generally coexisted, sharing cultural practices and traditions

PERSIA (IRAN)

In 19th-century Persia, the Qajar dynasty faced significant challenges from external forces, particularly from Russia. The Russo-Persian Wars (1804–1827) resulted in Persia losing key territories, including Georgia and Azerbaijan in the Caucasus. The Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 further diminished Persian sovereignty, ceding the southern portion of Afghanistan to Russia. As Russian influence expanded, it dominated foreign trade and gained control over northern Persian districts, revealing the inadequacy of the once-formidable Persian and Turkistan horsemen against European weaponry.

Russian imperialism in Persia was characterized by its gradual encroachment into the region. The Russo-Persian Wars (1804-1828) resulted in Persia’s loss of Georgia and Azerbaijan, while the Treaty of Turkmnchay (1828) granted Russia control over Persian trade and territory. Russia’s influence extended into northern Persia, where local leaders were coerced into accepting Russian patronage. The local population faced exploitation, displacement, and cultural erasure as Russian interests prioritized resource extraction and strategic expansion.

This map shows the location of Azerbaijan and its neighbors, including Iran, Georgia, Armenia, and Russia (Source: Wikimedia)

The Russian Empire’s treatment of local people in Persia was often brutal and exploitative. Peasants were forced into serfdom, while artisans and merchants faced economic marginalization. Cultural institutions, such as mosques and madrasas, were destroyed or converted to serve Russian interests. The local intelligentsia was suppressed, with dissidents facing imprisonment or exile. As Russian control deepened, Persian identity and autonomy were gradually eroded.

The Bakhtiari tribal confederacy, inhabiting the central Zagros Mountains and northeast Khuzistan plain of Persia, played a crucial role during this tumultuous period. Their organized structure, led by khans and the esteemed Ilkhani, ensured tax compliance and loyalty to the Persian government. However, disputes arose between two Bakhtiari families over the Ilkhani position in the late 19th century. With backing from Nasir al-Din Shah and British interests, both families received esteemed titles. One held the Ilkhani position (the supreme leadership title), while the other was granted the ilbigi title (a high-ranking deputy position).

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire faced major challenges due to ineffective leadership. A series of short-lived sultans—sixteen in total—struggled to maintain the empire’s power and unity. This instability allowed strong factions to emerge, creating internal divisions that outside nations exploited to reclaim or seize territory. Corruption became widespread during this period, undermining the authority of the government and diminishing public trust. Although there were some efforts at modernization, these initiatives were often inconsistent and hampered by external pressures from rival powers. As European nations advanced technologically and militarily, the Ottomans found themselves increasingly outmatched.

Throughout the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire lost significant territory to European nations. The Austrian Empire had already expelled the Ottomans from Hungary in the 18th century, and Austrian forces continued to threaten Ottoman lands into the new century. Nationalist movements within the empire led to the loss of critical regions, including Greece and Serbia, as these populations sought independence. The situation escalated in 1911 when Italy seized Libya, marking a significant incursion into Ottoman North Africa. This pattern of territorial loss reflected not only internal turmoil but also the broader context of European imperial ambitions. The cumulative impact of these losses severely weakened the empire’s geopolitical standing.

Among the various threats to the Ottomans, Russian expansion posed the greatest challenge. Throughout the 19th century, Russian armies steadily advanced southward, capturing vital Ottoman territories in the Caucasus. This growing Russian presence alarmed other European powers, particularly Britain, which feared that Russian dominance would upset the balance of power in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. In response, Britain and France allied with the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War (1854–56) to counter Russian advances. Although Russia continued to threaten Ottoman sovereignty, European intervention often provided a temporary buffer against total domination. Paradoxically, while European expansion represented a significant threat to the Ottomans, it also offered crucial support that helped sustain the empire during its decline.

During the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale and her team of nurses cleaned up the military hospitals and set up the first training school for nurses in the United Kingdom. (Source: Wikimedia)

The Ottoman Empire underwent significant reforms in the 19th century, starting with the removal of the powerful Janissary Corps in the 1820s. Sultan Mehmed II (1804-1839) cleverly orchestrated their mutiny, then brutally suppressed them, eliminating opposition and paving the way for further reforms. This marked a significant shift, as the Janissaries had long resisted change. Their removal allowed for modernization efforts to take hold. Western-style reforms followed, introducing the telegraph, postal service, and rail lines. University education was also revamped, adopting Western models.

Reforms continued with the enactment of a constitution in 1876, but were met with fierce opposition. Mahmud II’s successor, Abdul Hamid (1876-1909), sought to restore absolutist rule, persecuting those who advocated for further reforms. His rule lasted until 1908, but his repression sparked the emergence of liberal-minded groups. One such group, the Ottoman Society for Union and Progress, also known as the Young Turks, advocated for resumed reforms. Founded in 1889, they published pamphlets promoting their vision.

The Young Turks’ efforts eventually led to Abdul Hamid’s assassination in 1908, with military complicity, and his subsequent overthrow in 1909. Although they didn’t directly seize power, their ideas influenced the empire’s final decade. The restored constitution and freed press paved the way for promised reforms in administration, education, and women’s rights. However, political infighting and World War I’s onset stalled these efforts. Despite this, the Ottoman Empire made significant strides in modernizing its institutions and infrastructure.

The Ottoman Empire’s reform efforts aimed to revitalize the state and promote unity among its diverse populations. Key reforms included educational modernization, military reorganization, and secular law. Ottomanism sought to promote a shared identity among ethnic groups. While challenges persisted, the Tanzimat period laid groundwork for gradual modernization. The empire’s transformation continued until its eventual collapse, leaving a lasting legacy in the region.

A lithograph celebrating the Young Turk Revolution, featuring the sources of inspiration of the movement, Midhat Pasha, Prince Sabahaddin, Fuad Pasha and Namık Kemal, military leaders Niyazi Bey and Enver Pasha, and the slogan “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

The Young Turks published a new Constitution when they came to power in 1908. Modeled on both American and European constitutions, it sought to codify the reforms initiated by Mehmed II as indicated in the excerpts below: 3. It will be demanded that all Ottoman subjects having completed their twentieth year, regardless of whether they possess property or fortune, shall have the right to vote. Those who have lost their civil rights will naturally be deprived of this right. 9. Every citizen will enjoy complete liberty and equality, regardless of nationality or religion, and be submitted to the same obligations. All Ottomans, being equal before the law as regards rights and duties relative to the State, are eligible for government posts, according to their individual capacity and their education. Non-Muslims will be equally liable to the military law. 10. The free exercise of the religious privileges which have been accorded to different nationalities will remain intact. 14. Provided that the property rights of landholders are not infringed upon (for such rights must be respected and must remain intact, according to law), it will be proposed that peasants be permitted to acquire land, and they will be accorded means to borrow money at a moderate rate. 16. Education will be free. You can read the full Constitution here. |

|