7 EUROPE

At the outset of the 16th century, Europe’s population approximated 62 million, swelling to over 70 million by 1700. Northwestern Europe, particularly the Netherlands and Great Britain, experienced the most pronounced growth, with its population more than doubling. Urban centers expanded in size and significance as commerce and financial transactions converged around regular fairs held in cities.

Europe’s roads, averaging approximately one yard in width, accommodated both horsemen and carts, with adjacent footpaths for pedestrians. These thoroughfares connected the continent, facilitating increased travel and exchange as the population grew. Notably, they enabled scholars and scientists to traverse territorial boundaries, fostering the exchange of ideas and facilitating the dissemination of knowledge. Many prominent thinkers of the 16th century were born in one territory, educated in another, and worked in multiple others. For instance, Andreas Vesalius, author of a seminal work on human anatomy, was born in Belgium, studied in France and Italy, and published his book in Switzerland in 1543. Theophrastus von Hohenheim (Paracelsus), considered the “father of toxicology,” was born in Switzerland, studied in Austria and Italy, and embarked on extensive travels across Europe. The journeys of scholars like Vesalius and Paracelsus played a vital role in both acquiring and disseminating knowledge, ultimately yielding significant scientific breakthroughs, including the invention of the microscope (1590) and thermometer (1592).

The increasing interconnectedness of European society contributed to the significant political events of the 16th century. Eight influential factions drove conflict during this period:

- German nobles

- German and French Protestants

- Francis I, King of France

- French nobles

- The Pope

- Henry VIII, King of England

- The Ottoman Empire

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain

The 16th century was marked by persistent warfare and strife as the feudal system gave way to centralized state power and authoritarian leadership. Monarchs accumulated unprecedented political power and wealth, leading to conflicts often fueled by personal rivalries. The eight factions formed shifting alliances, frequently changing sides, and engaging in battles throughout the century. For instance, Francis I, a Catholic ruler, sometimes supported German Protestant nobles but also backed the Catholic Emperor Charles V. Additionally, he formed alliances with the Ottomans against Charles V, prioritizing the preservation of his own political power. Similarly, Henry VIII of England oscillated between supporting France and Charles V, seeking to maintain his kingship and control over English nobles.

A painting by Titian Vecili of Charles V in the 1550s. (Source: Creative Commons)

GREECE AND THE UPPER BALKANS

By the late 16th century, the Ottoman Empire had established political control over the Balkans, including Greece, granting local leaders significant autonomy. In the southern regions, a feudal aristocracy maintained large estates and fiefs, while some Greek families and merchants thrived in urban centers like Istanbul and Smyrna. However, the majority of the population lived in poverty, with limited access to resources and opportunities. Despite this, the eastern Balkans, comprising Bulgaria and Romania, emerged as a crucial supplier of cattle to Central Europe and Italy, exporting around 200,000 head annually. This economic activity brought some prosperity to the region, but it was largely concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy merchants and nobles. As a result, widespread poverty persisted throughout the Balkans.

The Balkans also harbored valuable natural resources, including mercury, which was mined in Idrija, a town in modern-day western Slovenia. This mercury was shipped to America, where it played a vital role in the silver mining process. Recognizing the economic significance of these mines, the Austrian Hapsburgs seized control of them in 1580, integrating them into their vast empire. This move underscored the region’s importance to European trade and commerce, as well as the competition for resources and influence that characterized the era. As the Ottoman and Hapsburg empires vied for power, the Balkans remained a contested and dynamic region, marked by both economic activity and social inequality. The complex interplay of political, economic, and social forces shaped the lives of people living in the Balkans, from wealthy merchants to impoverished peasants.

For ordinary people living in the Balkans during this time, life was marked by hardship and struggle. Most resided in rural areas, working as peasants or small-scale farmers, with limited access to education, healthcare, or social mobility. Their days were filled with manual labor, from dawn till dusk, with meager earnings and few comforts. Housing was basic, with many living in small, cramped homes made of stone or mud. Food was plain, with bread, cheese, and vegetables making up the bulk of their diet. Women’s lives were particularly constrained, with limited rights and opportunities outside the home, and often bearing the bulk of domestic and childcare responsibilities. Despite these challenges, community and family ties remained strong, with many finding solace in traditional customs, folklore, and religious practices. However, the ever-present threat of war, disease, and poverty hung over them, making life precarious and uncertain.

ITALY

In the 16th century, Italy was a fragmented region comprising independent city-states, which attracted the attention of powerful French and Spanish rulers. From 1494 to 1559, these two nations engaged in six devastating wars, known as the “Italian Wars,” to assert dominance over the peninsula. The conflicts ravaged Italy, leading to the sack of Rome in 1527 and the loss of independence for many city-states. Southern Italy fell under Spanish control, while northwest Italy was dominated by France. The Spanish established a governorship in Milan and viceroys in Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia. Although Genoa freed itself from Spanish rule after a prolonged revolt (1551-1569) with Ottoman aid, it remained economically tied to Spain. Despite its wealth and connections, Genoa’s lower class suffered greatly, with many forced to sell themselves as galley slaves during winter. Venice maintained its independence, but faced frequent threats. Naples, one of Europe’s largest and wealthiest cities, flourished due to its close relationship with the Spanish viceroy.

By the century’s end, most Italian cities had lost their independence and were financially drained. The population suffered from poverty, disease, and epidemics like syphilis (known as the “French Disease” in Italy and the “Naples Disease” in Spain), typhus, influenza, and the plague. Ironically, this period also saw the peak of the Renaissance, marked by extraordinary intellectual and artistic achievements. Notable figures like Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, and Leonardo da Vinci (who lived in Milan) made significant contributions to art and culture.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Explore the history of the Renaissance at the Annenberg Learning Website. Look at the some of the most important artwork of the Renaissance by exploring an online display of images at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

GERMANY AND AUSTRIA

In the 16th century, Germany was a fragmented region comprising numerous autonomous states, each governed by independent princes. Austria, a German-speaking territory, was a sub-kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire. Maximilian I, a member of the influential House of Hapsburg, ruled as Holy Roman Emperor from 1459 to 1519 and established his capital in Innsbruck. Through strategic marriages, Maximilian united various European political centers, marrying into the House of Burgundy, arranging for his son to marry Juana of Castile and Aragon, and securing marriages for his grandchildren with the royal families of Bohemia and Hungary. Maximilian’s grandson, Ferdinand I, succeeded him as king of Austria from 1503 to 1564. During Ferdinand’s reign, the region faced ongoing conflicts with the Ottoman Empire on its eastern border and social unrest in Germany and Austria, as peasants protested their persistent poverty and low living standards.

Maximilian holding his personal emblem, the pomegranate. Portrait by Albrecht Durer, 1519. (Source: Wikimedia)

Ferdinand’s brother, Charles, inherited the throne of Spain, where he was known as Charles I (1500-1558). In 1520, he was chosen as the Holy Roman Emperor and became known as Charles V. By 1550, the Habsburg Empire (based in Austria and Spain) had established control over Spain, southern Italy, Sardinia, Sicily, the Netherlands, the German states, Austria, parts of Hungary not controlled by the Ottomans, Bohemia, and much of Serbia. In addition, it controlled vast overseas holdings in the Americas. Austria, as the familial and political center of the Hapsburgs, had become the central political power in southern Europe.

The most important 16th century event in Germany was what has become known as the Protestant Reformation. In 1517, a Catholic priest by the name of Martin Luther (1483-1546) responded to the activities of a wandering Dominican friar named William Tetzel who had appeared in Germany. In an effort to raise money to finish the new St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Pope Leo X had promised that anyone who gave money to Tetzel would earn an indulgence. In exchange for a financial donation, an indulgence promised forgiveness of sins (past and present) and the release of relatives from purgatory. According to 16th century Catholic teaching, indulgences guaranteed that the person who received them and their loved ones would suffer less in purgatory. The Pope had commissioned Tetzel and sent him to Germany to sell these indulgences. When Tetzel approached Wittenberg, the capital city of Saxony, the local princely ruler, Frederick, asked Martin Luther, Catholic priest and professor at the University of Wittenberg, to approve Tetzel’s procedures. Luther refused because he did not believe that forgiveness of sins could be purchased with money. In response, Tetzel denounced Luther. Luther countered with the posting of 95 theses condemning various practices of the pope. This act is recognized to be the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

A painting of Martin Luther (Source: Creative Commons)

|

Learn More |

|

|

Chapter 10 explores the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Response in the Counter-Reformation. |

|

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Martin Luther’s Account of His Own Conversion The following is taken from the Preface to the Complete Edition of Luther’s Latin Writings. It was written by Luther in Wittenberg, 1545. Though I lived as a monk without reproach, I felt that I was a sinner before God with an extremely disturbed conscience. I could not believe that he was placated by my satisfaction. I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners, and secretly, if not blasphemously, certainly murmuring greatly, I was angry with God, and said, “As if, indeed, it is not enough, that miserable sinners, eternally lost through original sin, are crushed by every kind of calamity by the law of the decalogue, without having God add pain to pain by the gospel and also by the gospel threatening us with his righteousness and wrath!” Thus I raged with a fierce and troubled conscience. … At last, by the mercy of God, meditating day and night, I gave heed to the context of the words, namely, “In it the righteousness of God is revealed, as it is written, ‘He who through faith is righteous shall live.'” There I began to understand that the righteousness of God is that by which the righteous lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. And this is the meaning: the righteousness of God is revealed by the gospel, namely, the passive righteousness with which merciful God justifies us by faith, as it is written, “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates. |

|

|

Watch and Learn |

|

|

——————–———————- You can also watch the first and second part of a two-part series on the Life of Martin Luther produced by PBS.

|

|

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk who was both deeply read in theology and personally tormented by guilt and thoughts of the devil and demons. Luther was offended by Tetzel’s presentation of forgiveness as something that could be bought with money. To Luther, forgiveness was a divine gift which was received, not a reward to be earned. Luther argued that faith in Jesus brought salvation from Hell. In his zeal for what he considered to be the true message of the Bible, Luther argued strongly against what he thought was incorrect in the teachings and practices of the Catholic Church. He wrote and then distributed pamphlets and books in which he explained his beliefs and accused the Papacy of corruption. Significantly, Luther wrote in German so the people could read them. The printing press allowed Luther’s supporters to distribute his writings quickly throughout the German states. In response, the pope issued official statements of condemnation, known as papal bulls, against Luther.

As he aged, Luther became more defiant and rejected more of the teachings of the Catholic Church. What had begun as a repudiation of indulgences and corruption in the Church became a rejection of central Catholic doctrines and practices. Luther preached against the Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation. He rejected priestly celibacy both in his writings and practice. And he denied the role of the central Catholic role of the priest as an intermediary between the sinner and God. Many Germans for a complex set of reasons found Luther’s teachings appealing. Soon “Lutheranism,” as it became known, was a mass movement.

A pivotal event with far-reaching consequences occurred seven years after Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses sparked the Reformation. In 1524, the Peasants’ War broke out in southern Germany, as thousands of impoverished individuals rose up against both the nobility and clergy. Widespread violence swept across Germany, resulting in significant loss of life and property. Many nobles attributed the uprising to Luther’s revolutionary ideas, which they believed had incited the peasants. However, Luther denounced the Peasants’ War as immoral and condemned the violence as the work of the devil. He sided with the nobles, supporting their efforts to quell the rebellion. Ultimately, the nobility brutally suppressed the uprising, leveraging their military prowess to massacre hundreds of thousands of peasants. Social unrest continued to simmer, erupting again in 1552 as violence ravaged the countryside.

This episode reveals Luther’s contradictory role in the Reformation, as he simultaneously challenged and reinforced the existing power structures. On one hand, his ideas inspired the peasants to demand change, but on the other hand, he opposed their violent methods and sided with the nobility. Furthermore, Luther’s later writings reveal a darker side, as he espoused virulent antisemitism, calling for the persecution of Jews. This complexity underscores the need for nuanced understanding when evaluating historical figures, particularly in the context of intercultural competency. Understanding these contradictions is crucial for gaining a deeper insight into historical events and figures, allowing us to move beyond simplistic interpretations and engage with the intricacies of the past. By acknowledging and grappling with these paradoxes, we can develop a more informed and empathetic understanding of historical contexts and their continued impact on our world today.

The tumultuous period that followed the Peasants’ War eventually gave way to the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, a landmark agreement that brought a measure of stability to Germany. This peace treaty, signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the Lutheran princes, recognized the legitimacy of both Catholicism and Lutheranism in Germany, allowing each state to choose its own official religion. The Peace of Augsburg marked a significant shift towards religious tolerance and coexistence, ending the violent conflicts that had ravaged Germany for decades. However, it also solidified the territorial sovereignty of the German states, perpetuating the fragmentation of the Holy Roman Empire. The treaty’s provisions had far-reaching consequences, shaping the course of German history and influencing the complex web of alliances and rivalries that characterized European politics for centuries to come.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Read the Peace of Augsburg which made political restoration possible by accepting what had previously been regarded as an impossibility – namely, religious diversity. It decreed the toleration of those who accepted the Confession of Augsburg (1530), the definitive Lutheran doctrinal statement, in addition to those who held to the Catholic faith. |

SWITZERLAND

The Protestant Reformation expanded beyond Germany into Switzerland, where two influential reformers emerged: Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich and John Calvin in Geneva. Zwingli, a humanist-educated Catholic priest, began questioning Church practices like indulgences and clerical celibacy by 1508. By 1517, he advocated for a Bible-based religion, aligning with the German Reformation principles in 1521. Zwingli led both the new church and the city-state of Zurich.

Anabaptism emerged among the radical followers of Zwingli, as Conrad Grebel and George Blaurock rebaptized their group in 1525, calling themselves “Brethren.” After two decades of persecution, Menno Simons (1496-1561) shaped the movement’s permanent doctrine, emphasizing adult baptism, separation from the world, and literal adherence to Christ’s commandments. His followers became known as Mennonites. During the 16th century, Mennonites faced severe persecution, including execution, torture, and exile, due to their refusal to bear arms or swear oaths. This persecution resulted in significant suffering and loss of life among the Mennonite community and led to their migration to more tolerant regions, such as the Netherlands (1580s-1620s) and later North America (1680s-1720s).

William Farel (1489-1565) introduced the Reformation to Geneva, but John Calvin (1509-1564), a prominent theologian, became the city’s leading reformer after Zwingli’s death. Calvin’s doctrines, outlined in “The Principles of the Christian Religion,” significantly impacted France, England, Scotland, the Netherlands, and the United States. He emphasized human sinfulness and predestination, asserting that only the elect, chosen by God, would be saved. Calvin believed that salvation was a divine gift, but God alone determined who would be saved or damned. He saw proof of election in one’s actions, with the elect making choices that pleased God and avoiding those that displeased him.

A Painting titled “Portrait of Young John Calvin” from the collection of the Library of Geneva. (Source: Creative Commons)

Calvin’s theology also emphasized the state’s responsibility to uphold divine law, leading to severe punishments in Geneva for offenses like blasphemy, witchcraft, adultery, and heresy. Those found guilty faced capital punishment, including beheading or drowning. Conversely, Calvin prioritized education, establishing schools in Geneva to train future religious leaders who would disseminate his teachings throughout Europe. As a result, his influence expanded rapidly, with over two thousand congregations in France alone by 1561, and significant followings in the Netherlands, England, and Germany.

The Protestant Reformation’s leaders, including Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli, exemplified masterful persuasion techniques that remain pertinent today. By harnessing persuasive language, logical argumentation, and emotional connections, they successfully challenged deeply ingrained beliefs and sparked profound societal transformation. Capitalizing on widespread disillusionment with the Catholic Church’s wealth and corruption, as well as political grievances against oppressive rulers, they framed their message as a return to biblical fundamentals, resonating with their audience’s desire for spiritual revitalization and reform. Moreover, they effectively employed various media platforms, such as pamphlets, sermons, and letters, to disseminate their ideas and foster a sense of community among their adherents. These strategies offer valuable insights for anyone seeking to inspire change, underscoring the significance of understanding one’s audience, crafting a compelling narrative, and leveraging diverse communication channels to drive meaningful impact.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch this short video produced by the Khan Academy explaining the differences between groups of Protestants in the 16th century. |

SPAIN

The important rulers of the 15th century and architects of the Reconquista, Queen Isabelle and King Ferdinand, died in in the early decades of the 16th century. Their descendant, Philip II (1527-1598), emerged as the next significant leader in Spain. Their grandson, Charles V (1500-1558), succeeded them as the significant leader of Spain. Philip II (1527-1598), their son, became king in 1556 and ruled until his death in 1598. By the end of the 16th century, Spanish institutions and culture had established dominance over an extensive empire, including vast territories in the Americas. During this period, thousands of Spaniards migrated to the Americas annually. The Spanish Empire, bolstered by its military successes, exerted considerable influence across Europe, particularly from the early 16th century until the mid-17th century. Spain invested heavily in its military, with substantial portions of its revenue allocated to maintaining and expanding its armed forces.

However, the Spanish rulers faced a significant challenge rooted in their own beliefs and perceptions. They viewed the presence of large non-Christian populations (Muslims and Jews), who had lived in the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, as a threat to their authority and the unity of their kingdom. This perception was fueled by the belief that a unified Christian faith was essential for a strong and stable state. The rulers thought that the existence of non-Christians within their borders undermined this unity and posed a danger to their power.

It is crucial to note that this challenge was driven by the rulers’ own beliefs and biases, rather than the actions or behaviors of the Muslim or Jewish populations. These non-Christian groups had coexisted with Christians in the region for centuries, and many had developed complex identities that blended their original faiths with Christian practices.

In response to this perceived threat, the Spanish Crown employed the Inquisition. Established by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1478, the Spanish Inquisition operated under state control, unlike its medieval predecessors. Its primary objective was to identify and punish Jews and Muslims who claimed to have converted to Catholicism but were suspected of secretly practicing their original faith. Estimates suggest that between 40,000 and 100,000 Jews and at least 300,000 Muslims were forced to flee Spain in the 16th century. The Inquisition remained in place until its official abolition in 1834.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the Inquisition by reading this interview with historian Cullen Murphy. |

PORTUGAL

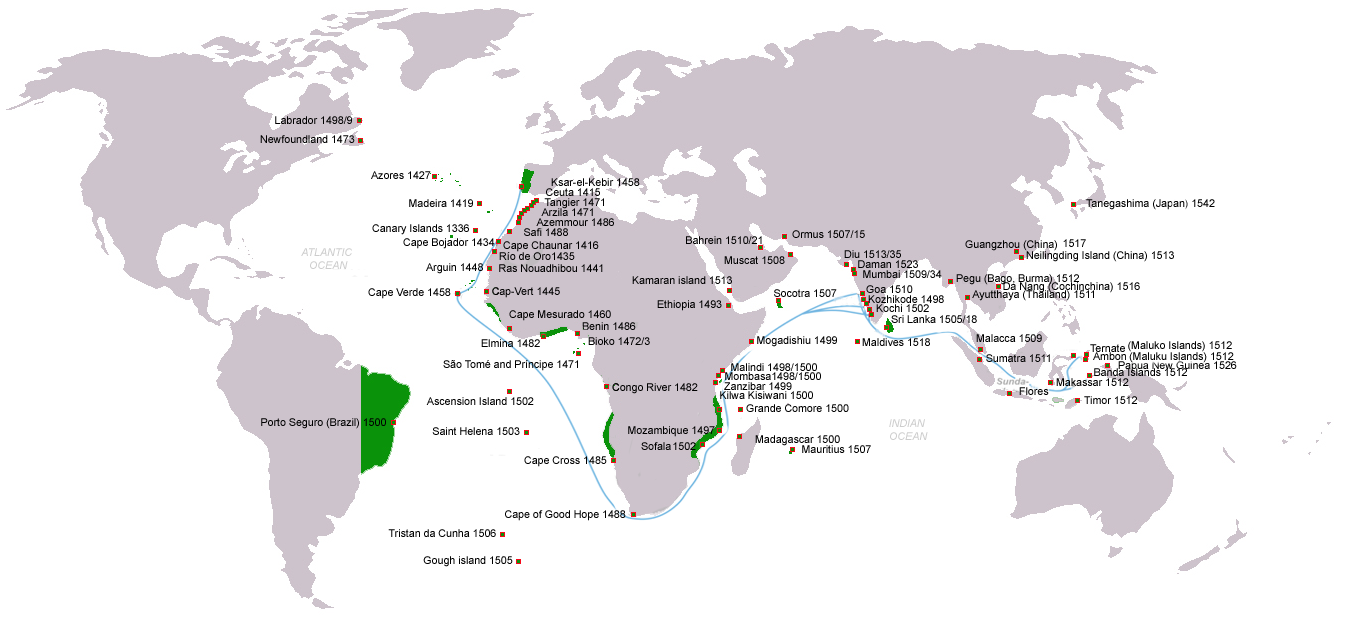

During the 16th century, Portugal expanded its vast empire, extending beyond its colonization efforts in South America. The Portuguese established a governor-led colony in India and fostered commercial ties with China. By the mid-16th century, they had constructed over 50 forts and trading posts, stretching from the east African coast to Nagasaki, Japan. The Portuguese developed massive ships, known as carracks, which dominated the seas with a displacement of up to 2,000 tons and a capacity to carry approximately 800 people. Equipped with lateen sails, these vessels achieved faster speeds and greater maneuverability over long distances, facilitating their extensive maritime trade networks.

A Painting of a large carrack attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder, circa. 1558. (Source: Creative Commons)

Portugal’s impact on indigenous populations in Africa and the Americas was profound and far-reaching. The transatlantic slave trade, fueled by Portuguese demand for labor in the Americas, forcibly relocated millions of Africans to plantations, resulting in immense human suffering and loss of life. Similarly, the colonization of Brazil led to the displacement, enslavement, and deaths of millions of Native Americans. The imposition of Portuguese culture, including forced conversions to Christianity, had a lasting impact on both groups. By the end of the century, pidgin Portuguese – a simplified language that emerged as a means of communication between people of different languages, characterized by a reduced vocabulary and grammatical structure – became the dominant language in the Atlantic region, facilitating trade and interaction among diverse groups.

In addition to their activities in Africa and the Americas, the Portuguese played a significant role in trade with India and East Asia. Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India in 1498 marked the beginning of a new era in spice trade, with Portuguese merchants establishing a presence in the Indian market. The Portuguese established colonies at Bombay Island (1534) and Macao (1557), and increased their influence in Sri Lanka. Their strategic bases at Mozambique and Zanzibar secured the sea route for Portuguese ships.

On the western African coast, the Portuguese exploited the African slave trade, establishing colonies at Angola and Guinea to supply labor for their American plantations. Although they were the first Europeans to establish trading colonies in Africa, they did not pursue sustained colonization or conquest. Instead, they maintained a strong presence through their involvement in the slave trade, with the closest connection being the colony at Guinea, situated on the notorious Slave Coast.

This map shows Portuguese discoveries and explorations in the 16th century; the main Portuguese spice trade routes are shown in blue. (Source: Wikimedia)

| Click and Explore |

| Learn more about the Age of Exploration by visiting the Mariner’s Museum’s interactive website. |

FRANCE

Francis I, who ruled France from 1515 to 1547, led the country during a period of significant military conflict. In 1515, French armies invaded Italy under his leadership, marking the beginning of the Italian Wars. The French forces achieved a notable victory by defeating a seasoned Swiss mercenary army fighting on behalf of the Pope near Milan. This conflict initiated nearly six decades of intermittent warfare between France and Spain. The Italian Wars saw various alliances and shifting fortunes, involving multiple European powers. The protracted struggle finally concluded with the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559, establishing a temporary peace between the warring nations.

A map of the center of Paris in 1550, by Olivier Truschet and Germain Hoyau (Source: Wikimedia)

The French monarchy used its power to suppress Protestantism in France, initially limiting its growth and impact. However, by the mid-16th century, Protestantism’s growth in France led to the Wars of Religion (1559-1598). This period saw France divided between Catholic and Calvinist factions, each backed by powerful nobles who exploited religious differences to further their own interests. Over the course of eight wars, these factions clashed, fueled by political and economic motivations. The conflicts finally subsided with the Edict of Nantes (1598), issued by King Henry IV, who had converted from Protestantism to Catholicism to secure his throne. This edict granted French Protestants (Huguenots) equal political rights, albeit with limited religious freedom, bringing an end to the religious and civil strife in France.

In the 16th century, Paris was France’s largest city, boasting a population of over 400,000 people. The city’s demand for wood for construction and heat was met by massive boatloads and giant floats, some reaching up to 250 feet in length, which arrived in Paris. Additionally, charcoal was transported from the forests of Othe in north-eastern France via the Sens River. King Henry III’s lavish style contributed to France’s reputation for high fashion, with his opponents claiming he wore an ostentatious 6,000 yards of lace at the 1577 Estates General in Blois. However, this opulence starkly contrasted with the lives of ordinary people, who struggled with poverty and hunger. In 1587, a staggering 17,000 impoverished individuals gathered under the walls of Paris seeking relief. In some years, the food supply in Paris was so inadequate that desperate people resorted to eating dogs, garbage, and rats. Widespread poverty and starvation were further exacerbated by repeated famines and food shortages that struck France throughout the century, with several severe episodes causing significant hardship.

The majority of the French population lived in rural areas, working as peasants or artisans, with limited access to education, healthcare, and social mobility. Women’s roles were primarily domestic, involving childcare, household management, and assisting with family businesses, while men worked in agriculture, trades, or as laborers. Many French men and women were deeply devoted to their Catholic faith, attending regular Mass, observing saints’ days, and seeking solace in prayer and confession. The Protestant Reformation, however, introduced significant religious tensions and conflicts, including the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), which led to violent clashes between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants). Life for ordinary French people in the 16th century was thus marked by significant hardship and struggle. Daily life was a constant struggle against poverty, hunger, and disease. Many people relied on charity, communal support, and the benevolence of local lords for survival. Despite these hardships, communities maintained various cultural and social practices that helped sustain social cohesion and cultural identity.

THE NETHERLANDS

Throughout most of the 16th century, the Netherlands was under Spanish Habsburg control, with Catholicism imposed on the region. However, the Dutch grew increasingly resentful of Spanish rule, leading to the outbreak of the Dutch War for Independence in 1568. This prolonged conflict, commonly referred to as the Eighty Years War, lasted until 1648. As the war raged on, seven rebellious regions united in 1579 to form the Union of Utrecht, laying the groundwork for the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (also known as the United Provinces). In 1581, this newly formed republic formally declared its independence from Spanish control, marking a significant milestone in the country’s struggle for self-determination. The United Provinces became a haven for Protestantism and religious tolerance, attracting persecuted minorities from across Europe. Despite ongoing Spanish efforts to exert control through military campaigns and economic blockades, the Dutch persevered, driven by their desire for freedom and self-governance. As the 17th century began, the Netherlands stood poised to emerge as a major economic and cultural power, its independence hard-won and fiercely cherished.

A map of the United Provinces drawn in the shape of a lion by Claus Jansz, 1609. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Excerpts from Erasmus, In Praise of Folly (1509) There were many critics of religion in the 16th century like Luther, Calvin, and Erasmus. Erasmus never left the Catholic Church, but he did point out the “stupidities and immoralities” of the Catholic Church and its clergy in his 1509 book In Praise of Folly. In this satirical work, as the passage below illustrates, the character of “Folly” praises herself and all her “followers,” including church officials and those who blindly follow them: [T]here is no doubt but that that kind of men are wholly ours [i.e., followers of Folly] who love to hear or tell feigned miracles and strange lies and are never weary of any tale, though never so long, so it be of ghosts, spirits, goblins, devils, or the like; which the further they are from truth, the more readily they are believed and the more do they tickle their itching ears. … Or what should I say of them that hug themselves with their counterfeit pardons; that have measured purgatory by an hourglass, and can without the least mistake demonstrate its ages, years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds, as it were in a mathematical table? Or what of those who, having confidence in certain magical charms and short prayers invented by some pious imposter, either for his soul’s health or profit’s sake, promise to themselves everything: wealth, honor, pleasure, plenty, good health, long life, lively old age … And what, are not they also almost the same where several countries avouch to themselves their peculiar saint, and as every one of them has his particular gift, so also his particular form of worship? As, one is good for the toothache; another for groaning women; a third, for stolen goods; a fourth, for making a voyage prosperous; and a fifth, to cure sheep of the rot; and so of the rest, for it would be too tedious to run over all. To read the entire book, visit the website of Project Gutenberg. |

|

ENGLAND

The 16th century was a transformative period in English history, marked by the reigns of King Henry VIII, Queens Mary and Elizabeth, and a flourishing literary scene that became known as the “Golden Age” of English literature. Henry VIII, who ascended to the throne in 1509 at just 17 years old, was a charismatic and confident young king, eager to make his mark on England and secure his dynasty’s future. While Henry VIII’s later years were marred by excess and tyranny, his early life was characterized by intelligence, ambition, and charm. He was determined to make England a cultural and artistic hub, rivaling the great cities of Europe. To achieve this, Henry VIII supported prominent intellectuals like Thomas More, a leading humanist who formed a close friendship with Desiderius Erasmus, the renowned Dutch scholar. More and Erasmus shared a passion for classical learning, humanist ideals, and literary pursuits, producing numerous works in Latin and Greek that showcased their intellectual brilliance. Their collaborations and individual writings had a profound impact on the development of English literature and culture.

As King Henry VIII (1491-1547) grew older, his desire for a male successor became an all-consuming obsession. In an era where dynasties relied on male heirs to secure their legacy, Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon, failed to produce a son, leading Henry to seek a divorce. However, the Pope refused to grant him an annulment, citing the validity of their marriage. This denial sparked a chain reaction of events that would change the course of English history. Thomas More, a devout Catholic and close advisor to Henry, opposed the King’s desire to divorce, defending the Pope’s decision. However, Henry, influenced by the ideas of Protestant reformer Martin Luther, saw an opportunity to break free from Papal authority. He sought to establish the Church of England, with himself as its head, thereby gaining control over religious matters and securing his desired divorce.

In 1529, Parliament convened and passed the Act of Supremacy, declaring the English monarch the Supreme Head of the Church of England. This bold move rejected Papal Supremacy and placed the church under royal authority. Thomas More, unable to reconcile his faith with the King’s actions, continued to object, ultimately leading to his tragic demise. Henry, now unfettered by Papal authority, ordered More’s execution in 1535, a stark reminder of the King’s unyielding desire for power and control.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about King Henry’s wives and what happened to them at Sir Thomas More was portrayed by Charlton Heston in the movie, A Man for all Seasons, in 1988. You can watch the trailer for this movie here. |

In 1531, King Henry VIII solidified his power by becoming the supreme head of both the Church of England and the English state. He appointed Thomas Cromwell as his chief advisor, tasked with enforcing the King’s authority and eliminating opposition. After Henry’s death in 1547, his son Edward VI ascended to the throne at just nine years old. However, Edward’s reign was short-lived, as he died at 15. A bitter succession crisis ensued, with supporters of his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth vying for power. Mary, a devout Catholic, ultimately claimed the throne and was crowned queen in 1553. Her reign was marked by a brutal persecution of Protestants, earning her the infamous nickname “Bloody Mary.” Notably, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a pivotal figure in the English Reformation and author of the first English Book of Common Prayer, was executed by burning at the stake during her reign

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Excerpts from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs John Foxe published his 3000-page book in 1563. In this book, Foxe tells the history of the Christian Church from the death of Christ to the accession of Queen Elizabeth I. This work of propaganda aimed to show the Catholic Church was evil and corrupt. Special emphasis was placed on the murders of English Protestants during the reign of Queen Mary. This book was widely read in the 16th century and played a significant role in promoting anti-Catholic prejudice and bigotry in the English-speaking world for centuries. The following passage comes from the end of the introduction to his book: I see no reason why the martyrs of our time deserve any less commendation than those of the primitive Church. They are assuredly not inferior to them in any point of praise whether we view the number of them that suffered, or greatness of the torments, or the constancy in dying. Consider the fruit that they brought to posterity and the increase of the Gospel. They watered the Truth with their blood. They taught us by their death to overcome such tyranny. Ought we not learn from their example, we who are now the posterity and the children of these martyrs, and being admonished by their examples? Read more about the book and the complete text of Foxe’s Introduction. |

|

Upon Mary’s death in 1558, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) ascended to the throne, determined to heal the religious divisions plaguing England. In 1559, she implemented the “Elizabethan Settlement” which established the Church of England as a via media (middle way) between Protestantism and Catholicism. This compromise allowed for diverse beliefs and practices within the Church, accommodating both Protestants and Catholics. While the majority of English people welcomed this compromise, a minority of Catholics and Protestants refused to conform. Notably, this nonconformist group gave rise to the Puritans and Pilgrims, who later settled the New England colonies in North America. The simmering religious tensions, however, ultimately contributed to the English Civil Wars of the 17th century.

During the latter part of Elizabeth’s reign, foreign trade emerged as a significant aspect of the English economy, and the late 16th century saw a surge in overseas expansion. The infamous English privateer Sir Francis Drake embarked on a groundbreaking voyage in 1577, navigating the Strait of Magellan and entering the Pacific. Drake’s exploits, including raiding Spanish ships and cities in Chile and Peru, made him a folk hero in England. The published accounts of his journey sparked widespread interest in exploration, laying the groundwork for English colonization in the Americas during the late 16th and 17th centuries.

The reign of Elizabeth I offers valuable lessons in perspective taking. Elizabeth’s ability to navigate the treacherous waters of religious conflict and find a middle ground, albeit imperfect, demonstrates the importance of considering multiple viewpoints. Her willingness to listen to and accommodate diverse perspectives helped maintain relative peace and stability in a tumultuous era. This approach also allowed her to harness the energy and expertise of various groups, fostering innovation and progress.

Sir Francis Drake in Buckland Abbey 16th century, oil on canvas, by Marcus Gheeraerts the Young (Source: Wikimedia)

IRELAND

When Henry VIII severed ties with the Roman Catholic Church in England, he also sought to assert his authority over the Irish Church. In 1536, the Irish Parliament recognized Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church of Ireland, marking the beginning of the English Reformation in Ireland. As a result, Henry confiscated lands from monasteries and churches, granting them to Irish chieftains who pledged allegiance to the English crown. This led to the decline of the traditional clan system and the emergence of a new nobility loyal to Henry. In 1541, Ireland was declared a kingdom, with Henry VIII as its king, solidifying English rule over the island.

Despite these changes, the Irish people remained devoted to Catholicism, which would later become a unifying force in their struggle for independence. Irish rebels, such as Red Hugh O’Donnell and Hugh O’Neill, continued to resist English rule, leading to ongoing conflicts and ultimately contributing to the Nine Years’ War (1594-1603). This period of rebellion marked a significant turning point in Irish history, as it paved the way for future struggles for Irish autonomy and self-governance.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch this short video produced by Lagan College in Ireland explaining the contentious relationship between England and Ireland in the 16th century. |

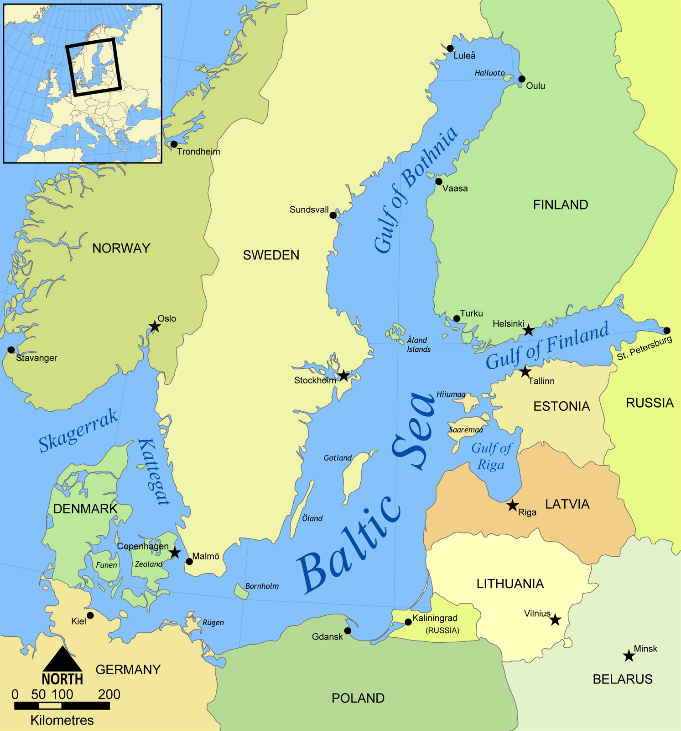

SCANDINAVIA and OVERSEAS SCANDINAVIAN CENTERS

During the 16th century, the Baltic region and the Gulf of Finland were largely dominated by the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Initially, these nations were united under a single monarch, as stipulated by the Union of Kalmar (1397-1523), with King John (1481-1513) ruling over the collective territory. Finland was considered a Swedish territory, and the entire region was subject to the Swedish crown. However, as the century progressed, the Scandinavian countries began to develop distinct identities and gradually drifted apart, eventually emerging as separate nations.

Notably, Scandinavia was still relatively sparsely populated, with a low population density of approximately 1.5 inhabitants per square kilometer, compared to the more densely populated Netherlands, which had around 40 inhabitants per square kilometer. This demographic difference had significant implications for the economic, social, and political development of the region. As the Scandinavian countries continued to evolve and assert their independence, they laid the groundwork for the modern nations of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland.

A Map of the Countries surrounding the Baltic Sea (Source: Wikimedia)

The “Little Ice Age” had a profound impact on the Norwegian settlement in Iceland during the 16th century. The expansion of Atlantic ice sheets, which extended unusually far south, severely disrupted shipping routes and devastated the Icelandic agricultural economy. The harsh weather conditions made it impossible for Icelanders to grow wheat, leading to widespread crop failures and famine. The effects were catastrophic, with the population experiencing an unprecedented 37 years of famine between 1500 and 1600. This prolonged period of food scarcity made life extremely challenging for the Icelanders, threatening their very survival. The “Little Ice Age” had far-reaching consequences for the Icelandic community, exacerbating social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities that would take centuries to recover from.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Read more about the history of Iceland by visiting this History World web page. To see amazing pictures of Iceland, visit this Guide to Iceland web page.

|

SWEDEN

In 1523, Gustav Vasa, later known as Gustav I (1496-1560), ascended to the Swedish throne, earning the title “Father of Sweden” for his transformative reign. Gustav’s leadership marked a significant turning point in Swedish history, as he implemented policies that stimulated economic growth and strengthened the country’s position in the region. During his reign, Sweden expanded its iron and copper mining operations, capitalizing on the country’s rich natural resources. This led to increased trade with neighboring countries, such as Denmark and Norway, and brought unprecedented prosperity to the Swedish people.

As the mining industry flourished, even peasants became involved in iron production, utilizing waterpower during the spring months to operate furnaces. However, despite this progress, Sweden’s vast territories remained largely unsettled, with scattered, isolated communities dotting the landscape. The country’s population was still relatively small, with many areas remaining unexplored and undeveloped. Nonetheless, Gustav’s reign laid the foundation for Sweden’s emergence as a major European power, setting the stage for its future growth and development.

POLAND

During the reigns of Kings Sigismund I (1506–1548) and Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572), Poland flourished culturally and politically. Sigismund I played a key role in consolidating the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and was known for his efforts to strengthen the state and manage internal and external challenges. His son, Sigismund II Augustus, continued these efforts and is remembered for his contributions to the Commonwealth’s growth. During this period, Poland became known for its relatively high level of religious tolerance compared to many other European states. The Warsaw Confederation of 1573, established under Sigismund II Augustus, was a significant milestone in guaranteeing religious freedoms, including protections for Greek Orthodox Christians and Jews.

Despite minor conflicts with neighboring nations over Baltic control, Poland flourished as a major European power. The lesser nobility’s influence grew, and their efforts to limit royal authority led to the passage of the Nihili Novi Act in 1505. This legislation transferred legislative powers from the king to the Diet, a representative assembly comprising all nobles. The Diet became the governing body of Poland, marking the country’s gradual transformation into a republic.

The Union of Lublin in 1569 formally united Lithuania and Poland, creating the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This period saw Poland’s greatest territorial expansion, artistic and intellectual advancements, and economic prosperity. The country’s strategic location allowed for the rapid spread of Lutheranism and Calvinism, leading to the National Diet’s declaration of religious freedom in 1552. However, the Catholic Church countered with the introduction of Jesuit priests in 1564, who successfully promoted Catholicism through education. In 1596, the Orthodox bishops of Ukraine and Lithuania actively chose to unite with Rome, while retaining their Orthodox rituals, through the Union of Brest, which created the Greek Catholic Church, allowing for a unique blend of Orthodox and Catholic practices.

RUSSIA

Throughout the 16th century, Russia’s pursuit of a Baltic port was a pressing imperative, driven by the need to access European markets and counterbalance the influence of rival powers. A Baltic port would enable Russia to tap into the Hanseatic League, a powerful mercantile alliance that dominated maritime trade in the region, thereby enhancing its economic prospects and strategic security. Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible, ascended to the Russian throne in 1533 with an expansionist agenda, seeking to augment Russia’s borders and trade opportunities. His conquest of Kazan in 1552 was a pivotal moment, granting Russia control over the Kama and Volga rivers, which connected Russia to the Caspian Sea and facilitated trade with Persia and Central Asia. Ivan’s subsequent annexation of the Astrakhan Khanate in 1556 further solidified Russia’s dominance in the region, paving the way for future trade and cultural exchanges.

A 18th-century portrait of Ivan IV. Images of Ivan IV often display a prominent brow and a frowning mouth. (Source: Creative Commons

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about Ivan the Terrible by watching this short video.

|

During the 16th century, a significant influx of immigrants from Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and England arrived in Russia, bringing with them new skills, technologies, and economic practices. The introduction of German coins and ingots led to the establishment of a regular currency system, albeit on a limited scale. Meanwhile, the Russian nobility faced challenges in maintaining control over the lower classes, particularly the peasants. In an effort to assert authority, the Moscow government mandated the registration of all peasants in 1592, followed by a decree in 1597 that allowed for the forced return of deserting peasants to their original landlords. This marked the beginning of a gradual erosion of peasant freedom, ultimately leading to the widespread institution of serfdom, which would come to define the lives of the majority of Russia’s population.

For Russian peasants, serf life was characterized by significant hardship and exploitation. Both men and women were subjected to rigorous labor and oppressive conditions. Serf women, in particular, faced an arduous existence, managing household duties, raising children, and working alongside their husbands in the fields. They were bound by patriarchal norms that reinforced their subordinate status and curtailed their autonomy. Serf men also endured grueling work for their landlords, often laboring long hours for minimal sustenance and inadequate living conditions.

Religion played a multifaceted role in the lives of serfs. The Orthodox Church provided a crucial sense of community and spiritual comfort, with many serfs drawing strength from religious practices and rituals. However, the Church also played a part in maintaining the social hierarchy, as landlords had substantial influence over the religious and spiritual lives of their serfs. Despite the oppressive conditions, serfs engaged in subtle acts of resistance and subversion, preserving folk traditions and customs as a form of cultural resilience.