31 THE AMERICAS

CANADA AND ALASKA

In the 18th century, diverse and thriving Indigenous nations inhabited the vast territories that are now Canada and Alaska. In the eastern regions of Canada, the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe peoples maintained vibrant communities, relying on the bounty of the forests and lakes for sustenance. Their skilled hunters and gatherers harvested resources such as beaver, deer, and wild rice, while their farmers cultivated crops like corn, beans, and squash.

Along the Pacific coast of Canada, specifically in present-day British Columbia, the warm waters of the Kuroshio Current nurtured lush forests, abundant salmon, and thriving Indigenous cultures. The Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuxalk, Tlingit, and Tsimshian nations flourished in this rich marine environment, harvesting salmon, halibut, and sea mammals in the waters off Vancouver Island, the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii), and the coastal regions of Alaska. These skilled fishermen and whalers developed advanced woodworking techniques, crafting magnificent totem poles, large lodges, and sea-gray canoes capable of holding up to fifty men. Their expert artisans also created intricate ceremonial regalia and ornate carvings. The social hierarchies of these coastal nations were complex, with hereditary leaders and a strong emphasis on kinship and clan ties. For centuries, these Indigenous communities maintained a deep connection to the land and sea, cultivating a rich cultural heritage that continues to thrive along Canada’s western coast.

A map showing the ancestral territory of the Tlingit peoples (Source: Wikimedia)

In the Arctic regions of Alaska, specifically the North Slope, Seward Peninsula, and Bristol Bay, the Inupiat and Yupik peoples developed unique cultures remarkably adapted to the harsh, icy environment. Their skilled whalers and seal hunters employed sophisticated technologies, such as kayaks, harpoons, and toggle-headed harpoons, to harvest the sea’s bounty, including bowhead whales, seals, and walruses. These nations were highly mobile, following the seasonal migrations of the animals they depended on, such as the annual whale migrations and the summer fishing runs. Their expertise in clothing design, using layers of animal hides, fur, and wool, and shelter construction, building igloos and sod houses, enabled them to thrive in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates. Through their traditional knowledge and resourcefulness, the Inupiat and Yupik peoples maintained a rich spiritual connection to the land, honoring the animals and natural forces that sustained them.

In the vast interior regions of Canada and Alaska during the 18th century, the Dene, Cree, and Athabaskan-speaking nations lived in close connection with the land, following seasonal migrations of animals like caribou while also hunting, fishing, and gathering. Their knowledge of the environment, passed down through generations, allowed them to skillfully sustain their communities. These nations practiced consensus-based governance, with elders and spiritual leaders playing important roles in decision-making. Cultural traditions such as storytelling, music, and dance were key to preserving their oral histories and passing down vital knowledge. Their deep understanding of the land and its resources fostered sustainable practices that ensured their long-term survival.

Despite their resilience and adaptability, indigenous peoples, known today as First Nations, in Canada and Alaska Native communities faced numerous challenges in the 18th century. Climate fluctuations, such as the Little Ice Age, along with natural disasters like droughts and famines, tested their resourcefulness. In some regions, inter-nation conflicts and rivalries over resources and territory also posed significant threats, often intensified by the growing fur trade. Additionally, diseases like smallpox, introduced by earlier European contacts, had already begun to weaken the populations of many Indigenous nations in Canada. However, in Alaska, such diseases would not become widespread until later European incursions. While some local environmental changes, such as overhunting and overfishing, emerged in response to shifting demands for trade, Indigenous nations largely maintained sustainable practices. Social and cultural changes, including shifts in leadership structures and spiritual movements, added further complexity to their lives. All of these challenges, though significant, were only a precursor to the profound disruptions caused by European colonization. In Canada, European settlers and traders had begun to alter Indigenous ways of life in the east, while in Alaska, the arrival of Russians later in the 18th century introduced new pressures that changed the lives and histories of Indigenous peoples in the region.

Alaska

The Russians “arrived” in 1728 when Russian explorer Vitus Bering launched a pivotal expedition from the Kamchatka Peninsula, navigating the waters now known as the Bering Strait. Although this journey did not immediately lead to Russian colonization, it sparked increased exploration and interest in the region. Bering’s voyage was part of a broader Russian effort to map Siberia and the North Pacific.

By 1745, Russian fur hunters had reached Attu Island in the Aleutian chain, seeking lucrative sea otter pelts prized in Chinese and European markets. However, their arrival sparked violent conflicts with the Indigenous Unangan (Aleut) people, who fiercely defended their homeland. The Russians used coercive methods, including forced labor and hostage-taking, to secure cooperation. The relationship between Russians and Unangan was marked by periodic violence and exploitation. Despite the Unangan’s expertise in hunting, they were treated as subordinates, forced to hunt sea otters and seals in exchange for survival. This system of coercion strained relations and undermined Indigenous autonomy.

In 1784, Gregory Shelikhov established a settlement on Kodiak Island, expanding Russian control. This marked the beginning of semi-permanent trading posts and strategic influence over the northern Pacific. The settlement relied heavily on Indigenous labor, entrenching Russian influence. The Russian-American Company, established in 1799, formalized Russia’s economic interests in Alaska. As a semi-governmental body, it controlled vast lands, enforced laws, and managed trade relations. However, its success depended on the coerced labor of Indigenous hunters, who were essential to profitability. This exploitative relationship persisted well into the 19th century.

Eastern Canada

In eastern Canada, French explorers, traders, and missionaries expanded their presence in the 18th century, focusing on the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River regions. Building on the foundations laid by Samuel de Champlain and Étienne Brûlé in the 17th century, the French sought to expand their territory, strengthen trade networks, and convert Native Americans to Christianity. Initially, many Indigenous communities, including the Huron-Wendat, Algonquin, and Mi’kmaq, viewed the French as valuable allies, gaining access to European goods and technology through the lucrative fur trade.

However, the French presence soon disrupted the balance of power among Native American nations. French alliances, particularly with the Huron-Wendat, antagonized the Iroquois Confederacy, sparking conflicts and displacement. European diseases like smallpox and influenza devastated Native American populations lacking immunity. Moreover, French missionaries imposed cultural and religious pressures, suppressing traditional practices and promoting European values. For example, Pierre-François Xavier de Charlevoix (1682-1761), a French Jesuit priest, worked to convert Indigenous peoples to Christianity in the early 18th century, primarily in the Illinois Country and the Great Lakes region, particularly around present-day Detroit and Montreal. He documented his experiences and interactions with Native American peoples, including members of the Illiniwek, Ottawa, and Huron-Wendat Nations, in his writings. These writings reveal the complexity of French interactions with Native peoples, highlighting both the violent displacement and cultural exchange that characterized colonial encounters.

The French colonial system transformed the economies of Indigenous communities, making the fur trade the dominant economic force. While some communities prospered, many became dependent on European goods, undermining their self-sufficiency. For instance, members of the Ottawa Nation, skilled hunters and traders, began to focus on providing beaver pelts to French merchants, leading to overhunting and depletion of their traditional food sources. The French diplomatic system created imbalances, eroding Native American autonomy. As French settlements expanded, Indigenous peoples faced growing pressure to adapt to European governance, religion, and culture, gradually eroding their sovereignty and traditional ways of life.

During the 18th century, the French government under Louis XV limited large-scale immigration to Canada, focusing on fortifying its North American territories. Between 1713 and 1743, France invested heavily in military infrastructure, including Fort Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island and strategic forts near Lake Champlain and Niagara Falls. The War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-1748) merged with the War of the Austrian Succession, resulting in French and Native American raids on New England, while British-allied Iroquois Nations attacked French Canada. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) brought a temporary peace, though hostilities remained. The mid-18th century also saw conflict in Nova Scotia, where English settlers clashed with local French inhabitants known as Acadians. Following the English victory, the Acadians were expelled, and many fled to French-controlled Louisiana, where they formed the cultural group now known as Cajuns.

The French and Indian War (1755-1763), part of the larger global Seven Years’ War, marked a decisive shift in North American history. Also known as the French and Indian War, it profoundly impacted North America, exemplifying the far-reaching effect of European conflicts on Indigenous populations and colonial settlements. Britain’s decisive victories, including the conquest of Quebec in 1759 and Montreal in 1760, led to France’s relinquishment of its Canadian territories. The Treaty of Paris (1763) formally solidified British control, marking a significant shift in the region’s political landscape. This transfer of power had lasting implications for the cultural, economic, and social dynamics of Canada. Ultimately, British rule reshaped the nation’s identity and trajectory.

In 1791, the British Parliament enacted the Canada Act, dividing the region into Upper and Lower Canada, a pivotal step in shaping the country’s administrative landscape. Concurrently, exploration of the Canadian Pacific coast gained momentum, with significant expeditions undertaken in the 1780s. Notably, Captain George Vancouver conducted a comprehensive survey of the region in 1792, mapping the coastline that would eventually bear his name. The following year, Alexander Mackenzie made history as the first European to traverse North America from coast to coast, accomplishing the feat via an overland route.

By the turn of the 19th century, trappers and traders had extensively explored the continent, crisscrossing the vast territory multiple times. However, tensions between Spain and Great Britain escalated into war, culminating in the Nootka Sound Incident in 1789. Spanish Captain Martinez seized four British ships, sparking a year-long dispute that was resolved through the Nootka Sound Convention in October 1790. This agreement recognized the rights of both nations to navigate, fish, and establish settlements in the Pacific, setting a precedent for future international cooperation.

THE UNITED STATES

Area of original 13 Colonies and Florida

At the start of the 18th century, the population of the British colonies in North America was around 250,000. By 1750, this number had grown to nearly one million, including 100,000 African slaves, making the colonies about one-third as populous as England. The growth continued, reaching 2.5 million by 1776. Early settlers mostly came from England, but as the century advanced, increasing numbers of Scotch, Welsh, Irish, German, and Dutch immigrants arrived. By 1763, the population was estimated to be 50% English, 18% Scotch and Scotch-Irish, 18% African, 6% German, and 3% Dutch. The colonies exported agricultural surplus like grain, meat, and butter to the Caribbean, which enabled colonists to purchase manufactured goods from England.

The British colonies in North America developed diverse economies, with tobacco becoming the leading export. By 1723, over 200 ships carried 3,000 kegs of tobacco annually to England, which re-exported it to northern Europe. Indigo and cotton also became important exports, with South Carolina shipping over a million pounds of indigo to England by the early 1770s. However, English restrictions on colonial currency, including bans on local minting and the export of English coins, hampered economic growth. Colonists relied on Spanish milled dollars, paper money, and bills of credit for transactions. Despite these challenges, industries like rum distillation using Caribbean molasses and Virginia’s iron production thrived.

By 1733, the 13 colonies had developed distinct systems of governance, currency, trade laws, and religious practices, operating mostly independently of one another. The Middle colonies (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) promoted religious and social tolerance, while the Southern colonies (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) were controlled by a plantation aristocracy. In contrast, the New England colonies (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut) were dominated by Puritan leaders. Cultural progress included the founding of colleges in Princeton, New York, and Philadelphia, and the 1704 launch of the first American newspaper in Boston. However, African slavery deeply shaped colonial society, and by 1720, enslaved people outnumbered white servants in all colonies south of Maryland. Resistance to slavery persisted, with numerous freedom struggles occurring throughout colonial history.

One notable example of these freedom struggles was the Stono Uprising (1739) in South Carolina. Led by a literate and charismatic enslaved African named Jemmy, approximately 100 enslaved individuals rose up against their enslavers, seeking liberty and escape from British rule. Marching towards Spanish Florida, they sought refuge and freedom. Although the uprising was ultimately suppressed, it highlighted the deep-seated desire for autonomy and self-determination within the enslaved community. The Stono Uprising remains a significant event in American history, demonstrating the ongoing pursuit of freedom and equality that would continue to shape the nation’s development.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the history of slave resistance in the Americas by exploring The Slave Rebellion website. |

European colonization sparked widespread conflict and violence across the Americas. As the 18th century began, tensions escalated. The War of the Spanish Succession, known in the colonies as Queen Anne’s War, sparked violence between English settlers in the Carolinas and their Chickasaw allies, and the Spanish and their Apalachee allies in Pensacola. In 1704, Governor James Moore led a military campaign into northern Florida, joined by 50 South Carolinian militiamen and allied Creek, Yamasee, and Apalachicola warriors. Moore’s forces and their allies killed over 1,300 Apalachee people and captured around 4,000 women and children in what became known as the Apalachee Massacre.

This brutal campaign was followed by further conflict in Carolina. The Tuscarora, an Iroquoian nation living in North Carolina’s Tidewater region, became increasingly alarmed by the growing alliance between European colonists and Algonquian Nations. In 1711, driven by concerns over land encroachment, unfair trade practices, and resource depletion, the Tuscarora launched an attack, which ignited a two-year conflict with both the colonists and their Algonquian allies. This war resulted in severe losses for the Tuscarora, with over 1,000 of their people being captured and sold into slavery.

The Yamasee War (1714-1717) proved even more devastating. Native American nations in the Carolinas, including the Muscogee, Cherokee, Catawba, and others, united to resist the escalating injustices perpetrated by white settlers. Key grievances included exploitative trade practices, which deprived Native Americans of valuable resources; slave trafficking, which saw the kidnapping and sale of Native individuals; and environmental damage from the expansion of rice plantations. These abuses led to a unified Native American resistance against colonial encroachment.

The war had disastrous consequences for both sides. Approximately 400 colonists, or 6% of the white population in the region, were either killed or displaced. For the Yamasee, the toll was even harsher: a quarter of their population was killed, enslaved, or forced to flee, causing significant disruption to their community. This conflict revealed the strained and often violent relationships between European colonizers and Native American nations and highlighted the destructive impacts of colonial expansion, including displacement, enslavement, and cultural upheaval. In the aftermath, many Native American groups were compelled to reorganize and relocate, forever changing the regional dynamics and leaving a lasting legacy of the harsh realities of the colonial period.

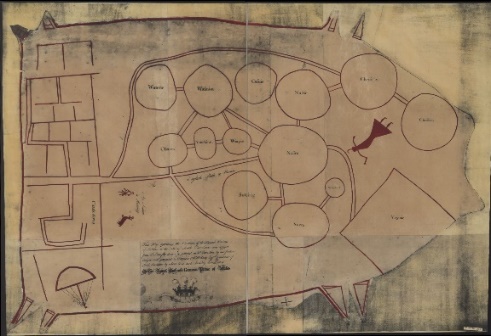

A 1724 deerskin Catawba map of the Nations between Charleston (left) and Virginia (right) following the Yamasee War (Source: Wikimedia)

Following the Yamasee War, the Creeks and Cherokees emerged as the two dominant Native American nations bordering South Carolina. For the Cherokee people in the 18th century, life revolved around traditional practices and communal living. They resided in small villages, typically consisting of extended family members, with homes made of log cabins or wooden frames covered with clay and thatch. Daily life began before dawn, with women tending to gardens, gathering firewood, and preparing meals, while men hunted and fished to supplement their diet. The Cherokee were skilled farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, and harvesting wild rice and berries. They also maintained vibrant spiritual practices, with rituals and ceremonies centered around the changing seasons and important life events. Family and clan ties were paramount, with children learning essential skills and stories from elders. Despite the increasing presence of European traders and colonizers, many Cherokee continued to live in harmony with the land, adhering to their ancestral ways. However, the encroaching forces of colonization and disease began to disrupt this balance, foreshadowing significant changes to come.

Similarly, the Creek people, living in what is now southern Georgia and eastern Alabama, maintained a rich cultural heritage in the 18th century. Creek villages, often consisting of several hundred people, were typically organized around a central square with ceremonial and communal spaces. Their economy thrived on agriculture, hunting, and trade, with women playing a crucial role in farming and food production. The Creeks were skilled craftsmen, renowned for their intricate pottery, woven baskets, and expertly crafted tools. Social organization was matrilineal, with property and social status passing through the female line. The Creeks also maintained complex spiritual practices, with rituals honoring the spirits of the land, animals, and ancestors. However, the Creek Nation faced significant challenges, including internal conflicts, European diseases, and encroaching colonization, which ultimately led to the formation of the Seminole Nation and the displacement of many Creek people.

As both the Cherokee and Creek nations navigated these complex challenges, European colonizers, including well-intentioned individuals like Christian Gottlieb Priber, sought to impose their cultural and religious values. Unlike many colonizers who exploited Native Americans for personal gain, Priber, a German scholar and lawyer, genuinely sought to understand and learn from Cherokee culture. He mastered their language and attempted to teach them about European customs, but his efforts ultimately conflicted with the interests of British colonizers who were exploiting Native Americans through deceitful trade practices. Priber’s attempts to reveal the traders’ fraudulent scales, weights, and measures threatened to expose these injustices, resulting in his imprisonment by local colonists.

Meanwhile, in the early 18th century, Georgia was established as the last of the southern colonies in 1733. Initially, the colony’s white population grew slowly under trustee rule, but by the eve of the American Revolution, Georgia had more than 18,000 free whites and a comparable number of enslaved individuals. Despite its original design to prohibit alcohol, outlaw African slavery, and limit landholdings, the colony continued to exploit Native American slaves. By 1750, the trustees reversed their stance and legalized all forms of slavery.

During the early 18th century, English Protestants intensified their missionary efforts, aiming to convert Native Americans to Christianity. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), established in 1701, spearheaded this initiative, boasting members such as colonial governors, commissaries, and influential laymen from both England and America. This organization’s close ties to English imperialism blurred the lines between spreading Christianity and expanding British dominance. As a result, the SPG’s missionary work became inextricably linked to colonial expansion. Despite establishing schools, including one affiliated with William and Mary College, attendance remained low, and overall progress was limited.

Throughout the 18th century, tens of thousands of Native Americans, including many women and children, were forcibly enslaved. European colonial customs, such as the practice of branding enslaved individuals, played a significant role in this tragedy. Branding was a method used to mark and control enslaved people, reinforcing their status as property. This brutal practice became a standard procedure, making it easier for enslavers to manage and exploit their captives. In 1716, commissioners managing the Carolina Indian trade exacerbated the issue by sending branding irons to agents in the backcountry, facilitating the marking of both deerskins and human captives.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about European enslavement of native peoples in the article, “America’s Other Original Sin.” |

The arrival of European settlers had severe repercussions for Native American populations in the 18th century, leading to widespread enslavement, violence, and displacement. Settlers often targeted Native American food supplies, deliberately destroying crops like corn to undermine their communities and facilitate land acquisition. As a result, many Native Americans were forced to abandon their ancestral lands and fled to the wilderness, where survival was challenging, and starvation was common. Even prominent leaders, such as Cherokee Chief James Vann (1760-1809), were displaced from their villages during the American Revolution and had to rely on scavenging for food. Despite these hardships, Native Americans had established advanced agricultural practices, with the “Three Sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—serving as staple crops. They prepared various dishes such as cornbread, hominy, and sofkee, a traditional soup made by boiling corn with oak and hickory ashes. By the late 18th century, sweet potatoes also became a widely cultivated crop.

Native American interactions with Europeans were multifaceted and dynamic. Each nation sought to exploit their relationships with Europeans to advance their own interests. This led to selective cooperation, as seen in 1742 when Creek, Yamacraw, and Cherokee peoples allied with Oglethorpe to repel Spanish attacks on St. Simon’s Island in Georgia. Conversely, Native Americans fiercely resisted colonists who threatened their way of life. Moreover, cultural and physical intermingling occurred, particularly as enslaved Africans who escaped integrated into tribal communities. Africans and Native Americans intermarried, learned each other’s languages, and occasionally collaborated against European colonizers.

Tribal identities evolved in response to European diseases, which decimated Native American populations, and land loss due to conquest. The Creek Nation, for instance, became a racially diverse entity in the 18th century. As Lower and Upper Creeks migrated to Florida, they merged with remnants of the Yamasee War and isolated groups to form the Seminole Nation. Similarly, North Carolina’s Lumbee Nation emerged as a melting pot of disparate remnant indigenous peoples, enslaved people who had escaped their bondage, and disillusioned white settlers, becoming one of the largest and most diverse Native Nations in the United States.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the Lumbee Nation (its history and culture) by visiting the official Lumbee website. |

The Mississippi Region and the Midwest

In the early 18th century, French explorers and traders dominated the upper Mississippi watershed, with Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founding Detroit in 1701 to control access to Lakes Huron and Erie. Native American nations, including the Shawnees, inhabited the eastern Midwest. By 1725, many southern Shawnee bands had rejoined their kin in Pennsylvania, but pressures from the expanding white frontier and Iroquois military activities pushed them westward. The Shawnees established new villages in the Wyoming and Susquehanna valleys, and some migrated south to seek refuge among the Upper Creeks in Alabama, while others settled along the Scioto River in central Ohio, surrounded by various nations such as the Potawatomi, Delaware, Wyandot, and Seneca.

The Midwest was rich in wildlife, including large buffalo herds in Illinois, which numbered up to 500 as late as 1792. However, by the early 19th century, hunting and farming activities drove these herds across the Mississippi River. In Minnesota, the Chippewa and Sioux experienced conflicts over wild rice resources in the northern lakes during the 1750s. The Sioux, whose oral traditions and cultural narratives hold that horses have always been an integral part of their history, adapted to a nomadic lifestyle that embraced their longstanding connection with horses.

For the Sioux people in the 18th century, life revolved around the rhythms of the Great Plains. The Sioux Nation comprised three main divisions: the Santee (Dakota), Yankton (Nakota), and Teton (Lakota), each consisting of various bands with distinct traditions and territories. Their traditional territory spanned the vast grasslands and river valleys of present-day North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Minnesota. The Sioux were skilled hunters, tracking buffalo herds and harvesting their meat, hides, and bones for tools and shelter. Women played a crucial role in processing and preserving food, as well as crafting beautiful quillwork and beadwork. The Sioux were also skilled farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash in the fertile river valleys. Their social organization was based on kinship ties, with seven council fires representing the seven original Sioux Nations. Spiritual practices centered around the Sun Dance, a sacred ceremony honoring the divine and ensuring the well-being of the people. Sioux warriors were renowned for their bravery and skill, defending their territory and protecting their families. As the seasons changed, the Sioux migrated to follow the buffalo, setting up temporary villages of hide-covered tipis and living in harmony with the land.

As the 18th century unfolded, the Sioux encountered increasing numbers of European explorers, traders, and missionaries. French explorers established early trade relationships with the Sioux, exchanging guns, ammunition, and cloth for furs and buffalo hides. However, these interactions also brought disease, displacement, and cultural disruption. Smallpox epidemics swept through Sioux communities, decimating populations and destabilizing traditional social structures. The Sioux also found themselves caught in the midst of European rivalries, particularly between the French and British, who competed for Native American alliances and control of the fur trade. By the late 18th century, the Sioux had begun to adapt to these new realities, forging strategic alliances with European powers and reconfiguring their traditional ways of life to accommodate the changing landscape.

The Sioux’s own experiences with European traders and explorers coincided with French colonization efforts in other regions, such as the Lower Mississippi Valley. A notable example was the establishment of Natchitoches, Louisiana’s oldest city, by French explorer Louis Juchereau de St. Denis in 1714. This strategic settlement was located near several small Native American states, including the Natchez Nation, which consisted of approximately 4,000 people living in seven villages along the Mississippi River. As one of the last remaining Mound-building cultures, the Natchez maintained their ancestral traditions and architectural skills, constructing elaborate earthen mounds for ceremonial and residential purposes. However, their resistance to European colonization was ultimately overcome by French military force. Outgunned and outnumbered, the Natchez lost their sovereignty and territorial control. The consequences were severe: up to 1,000 Natchez people were forcibly enslaved, marking the beginning of a prolonged period of displacement and cultural suppression.

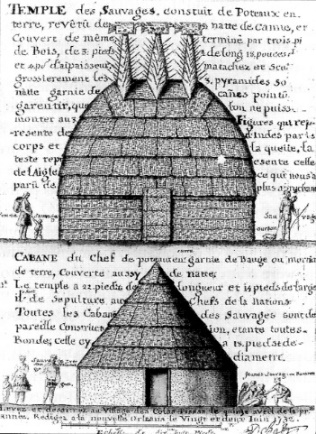

A drawing of the Natchez Great Temple on Mound C and the Sun Chiefs cabin by Alexandre de Batz in the 1730s (Source: Wikimedia)

The Upper Midwest, a vast territory surrounding the Great Lakes and bounded by the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, was home to various Native American nations. By 1750, the Shawnee Nation had fragmented into five semi-autonomous bands, each maintaining its own distinct identity within the tribal confederacy.

Within Shawnee communities, daily life revolved around the rhythms of nature. Families dwelled in wooden frame houses covered with bark and mats, often situated near rivers and fertile hunting grounds. Women tended to gardens filled with corn, beans, and squash, while men hunted deer, turkey, and buffalo to supplement their diet. Children learned essential skills from their elders, such as hunting, gathering, and craftsmanship. The Shawnee people placed great emphasis on kinship ties, with clans tracing their ancestry through maternal lines. Ceremonies and storytelling played vital roles in passing down cultural traditions and historical knowledge. As the seasons changed, the Shawnee would gather for festivals and celebrations, honoring the spirits that sustained their world.

Following the British takeover of the Great Lakes region in 1763, Ottawa leader Chief Pontiac (Obwandiyag) spearheaded a resistance movement, joined by members of the Wyandot, Potawatomi, and Ojibwa nations. They launched a siege on British-held Fort Detroit, which lasted from May to November. Emboldened by this success, the Shawnee pushed into eastern Ohio and West Virginia, targeting settlers who had encroached on Native American lands. They dispatched runners to Illinois, urging nations in the Wabash Valley to attack British forts and traders pouring into the region via the Cumberland Gap.

A map showing the Cumberland Gap in relation to the Wilderness route from Virginia to Kentucky (Source: Wikimedia)

Although Pontiac’s War (1763-1766) ultimately failed to expel the British from the Great Lakes region, it marked the beginning of a prolonged struggle against European-American expansion into Native American territories. This conflict foreshadowed the ongoing battles that shaped the region’s history. During the American Revolution (1775-1783), various Native American communities were drawn into the conflict as American colonists sought independence from British rule. Native Americans faced difficult decisions, including whether to take sides, risking land loss or navigating shifting alliances. Many groups, such as the Shawnee and Creek, allied with the British, hoping to resist American expansion. The British defeat and the subsequent Treaty of Paris (1783) resulted in the transfer of vast territories, including Native American lands, to the United States without their consent. This breach of trust fueled widespread disillusionment and continued resistance among these communities.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green explain the Revolutionary War and its impact on world history

|

Following the Revolutionary War, the newly independent United States faced significant challenges, including European skepticism and substantial war debt. In response, Congress proposed a new constitution, leading to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where delegates from 12 of the 13 original colonies drafted the framework for the new government. This pivotal moment set the stage for George Washington’s inauguration as the first President and John Adams as Vice-President.

The new federal government, under Washington and Adams, focused on securing the western borders and expanding territory. This expansion into the Ohio River Valley brought American settlers into conflict with the Shawnee, among other Native communities. U.S. attempts to assert sovereignty through treaties with the Shawnee in 1784, 1785, and 1786, which required the Shawnee to cede land claims east of the Miami River and acknowledge U.S. sovereignty, only intensified tensions. Despite promises of protection, trade agreements, and recognition of remaining lands, settlers repeatedly violated treaty terms. The Shawnee, supported by allies like the Miami, Potawatomi, and Delaware, resisted, leading to violent clashes. The situation escalated until 1794, when American forces under General Anthony Wayne defeated the Shawnee at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The Treaty of Greenville (1795) followed, resulting in the Shawnee and their allies ceding most of their ancestral homeland and being confined to northwest Ohio.

The Southwest and Pacific North West

The American Revolution had minimal direct impact on the sparse European and Native American populations west of the Mississippi River. This region was already shaped by complex trade networks, cultural exchanges, and conflicts. Spain claimed a vast territory encompassing present-day Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma, renaming it the Kingdom of New Mexico. White settlements primarily developed along the Rio Grande River, with Albuquerque established in 1706 and Taos founded soon after, near the Rio Grande del Norte. By 1750, Spanish settlers had reached Pueblo, Colorado. Extensive trade networks connected this region to Chihuahua, Mexico, over 600 miles away.

In the 18th century, diverse Native peoples inhabited the vast territories of the Southwest, including present-day California, Arizona, and New Mexico. The Ohlone, Miwok, and Modoc Nations thrived in California’s Central Valley and coastal regions, while the Tohono O’odham and Akimel O’odham inhabited southern Arizona. In the 18th century, the Diné (Navajo) and Apache peoples lived across the Four Corners region, which includes present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado. Both groups had deep cultural connections to this land, with the Diné known for their intricate weaving and the Apache for their varied subsistence practices. These nations developed complex societies, trading networks, and agricultural systems, often centered around rivers and oases.

Further north, the Pacific Northwest was home to numerous Native nations, including the Tlingit, Haida, and Salish. These coastal communities excelled at maritime trade, fishing, and whaling, with intricate social hierarchies and artistic traditions. The Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Umatilla communities inhabited the Columbia River Plateau, skilled in horse breeding and nomadic pastoralism. Despite their geographic and cultural differences, Native peoples shared a deep connection to their ancestral lands and resources, which would soon be disrupted by European colonization.

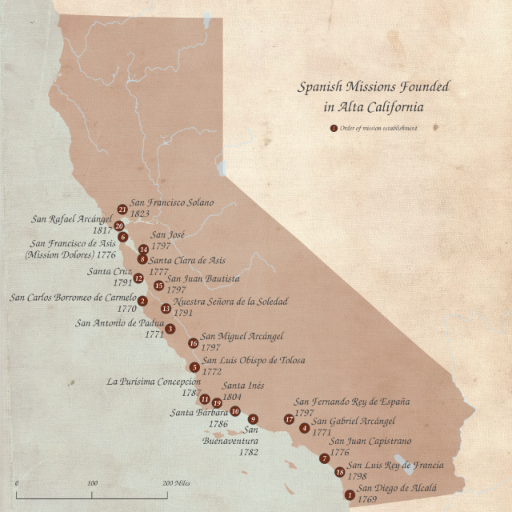

Throughout the 18th century, Spanish missionaries played a pivotal role in the colonization of the Southwest. Led by Franciscan friars, including Junípero Serra (1713-1784), missions were established in California, Arizona, and New Mexico to convert Native Americans to Christianity. These missions, such as Mission San Francisco (1776) and Mission San Juan Capistrano (1776), aimed to assimilate Native Americans into Spanish culture, often through coercive means. While some Native Americans adapted to mission life, many others resisted or fled, facing forced labor, disease, and violence. The missionary efforts ultimately disrupted Native American ways of life, leading to significant cultural, social, and economic changes.

In the 18th century, Spain expanded its control in the Pacific coastal regions through concurrent land and sea exploration. Father Eusebio Kino, a pioneering explorer, charted the territory between Mexico and California, venturing as far as San Diego in 1769 and establishing missions in the Baja Peninsula. However, Spanish authorities grew concerned in the 1750s upon hearing rumors of Russian interest in upper California, a region considered integral to New Spain. Despite the Russians’ true intention – harvesting sea otter pelts – King Charles of Spain responded decisively, ordering the construction of a fortified chain along the California coast.

Resistance to Spanish colonization occurred periodically across the southwestern region of North America. In the 1770s, Apache and Comanche forces, driven by grievances over land encroachments and abuses, united in a series of coordinated attacks against the Spanish, causing substantial losses and disrupting Spanish settlements. This period of conflict, marked by fierce resistance, demonstrated the resilience and strategic capabilities of Native American groups defending their territories. However, the response to Spanish expansion varied among different communities. For instance, the Akimel O’odham of what is now southern Arizona chose a different path. Rather than resisting, they maintained amicable relations with the Spanish, leveraging their interactions to secure favorable trade agreements and support. The Akimel O’odham, numbering around 2,500, thrived as sedentary farmers with a rich agricultural tradition. They cultivated essential crops like corn, squash, and cotton, utilizing sophisticated irrigation techniques that allowed them to flourish in the arid environment. Their advanced irrigation systems, including canal networks and terracing, were crucial for sustaining their agriculture and supporting their vibrant communities. The diverse responses of Native American groups to Spanish colonization highlight the complexity of the region’s history and the varied strategies employed by indigenous peoples in navigating colonial pressures

The intricate relationships among Native American communities, Spanish colonizers, and the land defined the history of the Kingdom of New Mexico. As Spanish control expanded, Native American groups responded in diverse ways, with some resisting and others cooperating or remaining neutral. The legacy of Spanish colonization continues to influence the cultural and economic landscape of the region, providing essential context for understanding its modern-day dynamics.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the irrigation system used by the Akimel O’odham peoples who had inherited the system from their Hohokam ancestors in this article published by Popular Archaeology.

|

MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA, AND THE CARIBBEAN

Spanish rule continued in this region with the goal of enriching the Spanish Crown and spreading Catholicism, often with little regard for the impact on the local population. King Felipe V of Spain introduced reforms in the 18th century, which helped boost the economy in some areas, though the effects were not the same everywhere. By the end of the century, the population was growing again, partly because people had developed some immunity to European diseases, but also due to more stable farming and urban growth.

A wealthier class began to emerge, especially among Creoles (criollos), leading to cultural and intellectual changes, especially in cities like Mexico City. However, this group was still part of a strict caste system, and colonial society remained deeply divided by race and class. By the late 1700s, Mexico City had over 100,000 people, making it larger than most cities in Europe, except for Paris and London. Mexico’s population was also larger than that of the thirteen British colonies in North America. The northern silver mines allowed Mexico to trade extensively with Europe, though a corn shortage in 1785–86 led to a famine in the mining areas, forcing many workers to flee south to cities like Mexico City.

Guatemala City was rebuilt in 1776 after an earthquake destroyed the old capital. In Central America, British influence grew, especially in areas like the Gulf of Honduras, the Miskito Coast, and Panama. The British used these regions as a source of enslaved Indigenous people and began establishing control over territories like Belize, though full colonial rule there came later in the 19th century.

In the Caribbean, coffee production began on Martinique in 1723, and by the end of the century, the Caribbean islands were supplying 90% of the world’s coffee. Sugar remained the primary crop in Jamaica, while Saint Domingue (modern-day Haiti) rivaled Jamaica’s production. By the 1780s, Saint Domingue was one of the richest colonies in the world, producing huge amounts of sugar and coffee on large plantations run by enslaved workers.

The French Revolution had a major impact on Saint Domingue (later renamed Haiti), where tensions between social groups were high. The colony’s population included about 500,000 enslaved people, 40,000 Europeans, and 30,000 free people of color, many of whom were mixed race. Despite their wealth, the free people of color faced discrimination. The harsh conditions on sugar plantations and the unequal society led to unrest, which eventually contributed to the Haitian Revolution—the first successful slave revolt in history, resulting in the creation of an independent Haiti.

When news of the French Revolution reached Saint-Domingue, the wealthy white elite initially supported it, seeing an opportunity to escape the heavy taxes imposed by the French crown. As revolutionary ideas began to circulate on the island, both free people of color and enslaved people embraced them, though for different reasons. To the free people of color, the Declaration of the Rights of Man, passed by the French National Assembly on August 26, 1789, seemed to promise equal treatment for all free individuals. For enslaved people, the implications were even more profound. If, as the Declaration stated, “men are born free and equal in rights,” then slavery itself was clearly unjust and immoral.

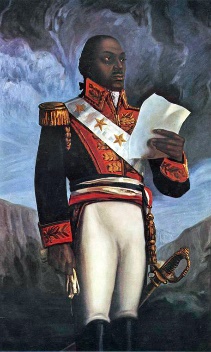

In 1791, a rumor spread that the King had declared all enslaved people in the French Empire free. The rumor ignited a powerful uprising, as enslaved people rose up to seize their freedom. They set fire to over a thousand plantations and overcame those who tried to stand in their way. The result was social chaos, as freed blacks, enslaved people, and white colonists fought for control and their own visions of liberty. Amid this turmoil, power began to shift toward the enslaved population, led by Toussaint Louverture, a former slave who became the leader of the revolution. Louverture, and later his successors, managed to overcome both internal opposition and external threats, including negotiations with Napoleon Bonaparte. This ultimately led to the establishment of Haiti as an independent nation, named after the Indigenous word for “mountainous land.”

A 19th century painting of Louverture in military uniform (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch as John Green explains the Haitian Revolution – its history and its significance in world history – in Crash Course in World History #30. |

On July 7, 1801, Haiti’s Constitution solidified Toussaint Louverture’s lifetime governorship and formally abolished slavery. The Haitian Revolution, renowned as the world’s sole successful large-scale slave revolt, culminated in Haiti’s declaration of full independence on January 1, 1804, under Jean-Jacques Dessalines. This pivotal event had far-reaching repercussions across the Atlantic world. For Indigenous peoples in South America and enslaved individuals in the Caribbean, Haiti’s revolution embodied hope and resistance against oppression.

The Power of Perspective: How Toussaint Louverture’s Story Challenges Our Assumptions on Race, Power, and Freedom

Toussaint Louverture, the former slave-turned-revolutionary leader, embodies the complexities of human experience and the power of perspective. Born into bondage in 1743, Louverture’s life was shaped by the brutal realities of slavery and the French colonial system. Yet, he rose to lead the Haitian Revolution, liberating his people and challenging the very foundations of colonialism. Through his lens, we see the inherent contradictions of Enlightenment ideals and the hypocrisy of European powers preaching liberty while enslaving millions. Louverture’s story humanizes the enslaved, revealing their capacity for strategic leadership, military genius, and unwavering dedication to freedom. As we consider his legacy, we are compelled to confront our own biases and assumptions about race, power, and humanity. The enduring legacy of Toussaint Louverture reminds us that the fight for justice and equality remains urgent, compelling us to challenge entrenched power structures and promote human rights.

The revolution’s impact was immediate and profound. Enslaved people in Jamaica composed songs celebrating the 1791 uprising, while slaveholders reported a surge in defiance among enslaved populations inspired by Haiti’s bravery. The name “Haiti” became synonymous with resistance to slavery’s cruelty, influencing acts of resistance, such as the 1811 Louisiana slave revolt. Abolitionist movements in the United States and Great Britain also drew inspiration from Haiti’s struggle.

However, the Haitian Revolution sparked fear and hostility among white elites worldwide. In response, enslaved peoples in the Caribbean, Brazil, and the United States faced harsher treatment. The United States, under President Thomas Jefferson, refused to acknowledge Haiti’s independence and imposed a crippling economic embargo. France further strained Haiti’s economy by demanding an “independence debt” of 150 million francs in 1825, severely hindering Haiti’s development for years to come.

WESTERN AND NORTHERN COASTS OF SOUTH AMERICA

In Spanish-controlled South America, a stark contrast existed between the powerful European colonists and the exploited and marginalized Indigenous population, who harbored deep-seated grievances against their colonial rulers. This tension culminated in significant uprisings, most notably the rebellion led by Túpac Amaru II in Peru from 1780 to 1781. Túpac Amaru II claimed royal Inca descent and aimed to overthrow Spanish colonial rule, abolish the oppressive mita (forced labor) system, and reduce taxes. His movement initially garnered widespread support, but Spanish forces brutally suppressed the revolt, resulting in thousands of Indigenous deaths and further repression. This brutal suppression highlighted the deep-seated dissatisfaction with colonial rule.

Meanwhile, European powers continued to vie for control over strategic South American ports. The British attack on the Spanish fortress at Cartagena, Colombia, in 1741, led by Admiral Edward Vernon, was a notable conflict. Despite initial confidence, the British forces were repelled by the Spanish, aided by devastating outbreaks of malaria and yellow fever. This defeat underscored the resilience of Spanish colonial rule, but also demonstrated the ongoing interest of European powers in the region. The struggle for control would continue to shape the region’s history, influencing the complex web of alliances and rivalries.

In Venezuela, economic development was uneven. The Caracas Company established cocoa plantations in 1728, driving growth in the region. However, the southern areas remained largely undeveloped, with native peoples, mestizos (people of mixed ancestry), and creoles engaging in subsistence farming and managing extensive herds of sheep. In contrast, the notorious Potosi mining camp in Bolivia continued to operate under harsh conditions, leaving miners in poverty while merchants reaped significant profits. This disparity highlighted the need for economic reform and greater equality. The uneven development also contributed to growing discontent among South Americans, fostering an environment in which revolutionary ideas could take root.

Toward the latter part of the 18th century, Spain introduced economic reforms aimed at revitalizing its colonies. Under King Charles III’s enlightened rule, these reforms included the liberalization of trade within Spanish America, allowing colonies to exchange goods and ideas more freely. This facilitated the spread of Enlightenment philosophies, sparking discussions about self-government and laying the groundwork for future independence movements. Although the French Revolution temporarily delayed these movements, the seeds of change had been sown. The gradual shifts in Spain’s colonial policies, combined with growing discontent, ultimately paved the way for the region’s struggles for independence in the early 19th century.

EASTERN COAST AND CENTRAL SOUTH AMERICA

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) forged an alliance between Portugal and England, prompting French attacks on Brazilian ports, including the devastating sacking of Rio de Janeiro in 1711. Meanwhile, tensions between Portuguese colonizers and Indigenous peoples persisted, marked by open warfare that pushed the Portuguese frontier deeper into the jungle. The conflict between Native Brazilians and Portuguese settlers in Recife (1710-1711) ultimately resulted in Portuguese control, leading to Recife’s status as capital until 1763, when Rio de Janeiro became the capital due to nearby gold discoveries. Brazil’s gold production peaked between 1750 and 1755, with over 15 tons extracted annually. The country also exported sugar, coffee, cacao, rice, and cotton to Europe, relying heavily on enslaved African labor. By 1775, over 5.5 million enslaved Africans had been forcibly brought to the Americas, with Brazil’s death rate being particularly alarming, as four out of five enslaved individuals died within eight years of arrival.

In the 18th century, the Araucanian Indians, also known as the Mapuche peoples, continued to resist Spanish colonization, maintaining their independence through strategic alliances and adaptability. Some had evaded Spanish control in the 16th century by fleeing to the eastern slopes of the Andes with stolen Spanish horses. From this refuge, they periodically launched invasions into the pampas, even threatening Buenos Aires. Argentina capitalized on this instability by selling thousands of mules annually to Peru and Brazil, where they facilitated the transportation of goods, including silver and gold. Up to two million mules were utilized in Central and South America during this period, primarily for transportation. European oxen, well-suited for pulling carts in the pampas, became integral to the region’s agriculture, while gauchos honed their expertise in riding the region’s renowned horses.

A painting shows the Araucanian Indians subduing horses (Source: Wikimedia)

By the late 18th century, Brazil and Argentina’s economies had become deeply entrenched in the global market, fueled by the exploitation of African and Indigenous labor. European livestock and agricultural practices transformed the pampas’ landscape, while the transatlantic slave trade had catastrophic consequences for millions of enslaved individuals. The region’s social and economic dynamics were shaped by colonialism’s harsh realities and vast inequalities. This complex web of exploitation and resistance forged the foundation of modern Brazilian and Argentine societies.

The convergence of colonialism, slavery, and economic expansion had far-reaching consequences for the region’s Indigenous populations and enslaved Africans. As European powers vied for control, the native populations faced displacement, violence, and cultural erasure. The brutal realities of the transatlantic slave trade and colonial exploitation continue to reverberate through the region’s history, underscoring the need for a nuanced understanding of the complex forces that shaped the Americas.