11 MAKING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN EVENTS: The Columbian Exchange and Slavery

Although we commonly use these terms, it is incorrect to refer to Europe as the “Old World” and the Americas as the “New World” since both South and North America were only “new” to the Europeans who “discovered” them. In fact, people had been living there for thousands of years. Instead, it is useful to think of the period around Columbus’ voyage to the Americas as one in which the people of western Eurasia (Europeans) began to mix more frequently with those of eastern Eurasia, Africa, and the Americas. For the people of Europe, who before this period had little knowledge of such vastly different cultures, this did create a “New World

The Columbian Exchange and Slavery

As we have already learned, the phrase Columbian Exchange refers to the large-scale transfer of people, plants, animals, and diseases between Eurasia and the Americas, which had previously existed as separate ecosystems. Products from the Americas became very popular in Europe. New foods like potatoes, corn, and tomatoes were introduced into the European diet. In later centuries, potatoes were widely cultivated because they were a cheap crop; when potato blight struck in the late 1840s, for instance, the crop was so widely in use that it caused a catastrophe across Europe, especially in Ireland, where more than one million people perished. More exotic foods like chocolate, another mainstay of the present European diet, were imported from the Americas. In present day Canada, a seemingly limitless supply of fish and furs drew the French, and to a lesser extent the Dutch, to establish settlements and trade with Native Americans.

Nautical map of Africa and the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) by Lazaro Luis, 1563. (Source: Wikimedia)

European exploitation of the Americas also gave license to produce large quantities of products that Europeans already found desirable. The plantation economy was a widespread model for early colonial enterprises. The Spanish, Dutch, and French all set up large sugar plantations in the Americas, while in Virginia, British entrepreneurs undertook the widespread cultivation of tobacco. Later, cotton plantations in the Americas would become an integral part of transatlantic trade.

|

Click and Explore |

|

For an overview of the animals and plants that were part of the Columbian Exchange, visit the “The Columbian Exchange at a Glance” webpage at Lumen Learning. |

The Spanish discovery of gold in the Americas was one of the chief inspirations for other colonial settlements. Few of the other European nations were as successful in their search for gold. The Portuguese eventually found gold in Brazil in the late 1690s, but the gold rushes in North America did not occur until after the colonial period had ended. To the extent that the other European countries capitalized on the mineral wealth of the Americas, it was at the expense of the Spanish; Spanish galleons transporting Mexican silver back to Europe were a tempting target for Dutch and English pirates.

The exploitation of the Americas required massive amounts of labor, whether to cultivate tobacco fields in Virginia or to work silver mines in Mexico. Europeans turned to various sorts of exploitative labor. In Virginia, plantation owners relied on a mix of indentured workers and slaves, and even in New England some farmers owned slaves, though slavery was outlawed there late in the eighteenth century. Most slaves, however, went to sugar plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil. The job of bringing the slaves from Africa fell mostly to the Portuguese, who brought millions of slaves across the Atlantic over four centuries, mostly from their central ports in Guinea and Angola.

Guns and Germs

While Europeans benefited greatly from the Columbian Exchange, the peoples of the Americas were not so fortunate; rather, they suffered greatly as a result of contact with Europeans. Europeans decimated Native American societies in war, and the introduction of guns gave native peoples an easier means to make deadly war among themselves. The introduction of European diseases also decimated indigenous populations.

Contact between Europeans and the peoples of the Americas was congenial at first. When Columbus first landed in the Bahamas, he found the people there to be generous. Later colonizers had similar first impressions. In many cases, the locals welcomed the Europeans onto their land, gave them gifts, and taught them to survive. A relationship of rough equality even persisted throughout much of the existence of the French colony in New France, brought on by the harsh climate and mutual dependence in the fur trade.

In most cases, however, the initial relationship of equality degraded into conflict and often warfare. Native peoples were not always passive victims; in many instances they raided European settlements, and occasionally they massacred Europeans. The Europeans, however, with weaponry far more advanced than that used by native peoples, were almost always the victors throughout centuries of settlement.

Warfare was a constant for the colonizers, not only with the local populations, but also among themselves. Europeans exported their conflicts wherever they went. For instance, the Dutch massacred English traders in Indonesia in the 1600s and destroyed the English colony at Ferryland, Newfoundland in the 1670s. The French colony of Acadia was destroyed by Basque raiders in the 1630s, moved, and was then conquered by the English, who controlled it from 1654 to 1667, when the French got it back. The English then took it again in 1713, at the end of the War of Spanish Succession, and in 1755 all of Acadia’s inhabitants were deported because of their sympathy for the French. European conflict again came to North America in the 1750s with the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, in which France and England were again on opposite sides. In 1759, the British successfully besieged the French stronghold at Quebec, and when the war ended, they received all of France’s territories in North America.

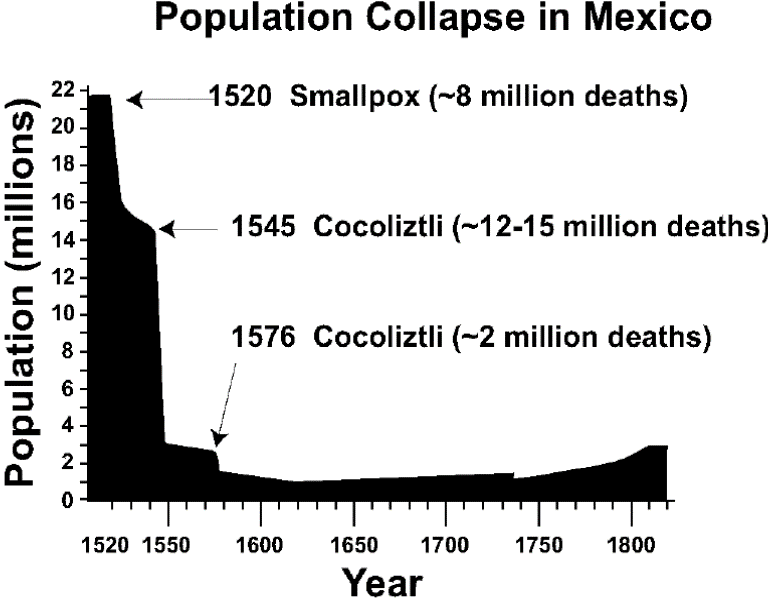

A graph showing the population collapse in Mexico after European exploration. (Source: Wikimedia)

Conflicts between the British and French in North America also involved the Native Americans. The settlers of New England and New France allied with the Iroquois and the Huron respectively, and both sides became involved in European conflicts. The English alliance with the Iroquois was one of the factors in the near extinction of the Huron. The English had little compunction about giving guns to the Iroquois, while the French only gave guns to those who had converted to Christianity. In a critical battle in 1649, the Iroquois’ superior firepower helped them to break through the Huron defenses and scatter the tribe. Native American tribes also fought on both sides in the Anglo-French struggle over Quebec in the Seven Years’ War from 1756-1763.

Germs, however, were perhaps the most destructive legacy of European settlement. When the European colonizers brought products, resources, and people across the Atlantic, they also brought numerous diseases with them. While Europeans had all developed partial immunity to diseases like smallpox, chicken pox, tuberculosis, and measles, the inhabitants of the Americas had not. These diseases decimated Native American populations throughout North and South America.

Settlement

European exploration opened up new opportunities for the adventurous, and nowhere was this more the case than in the Americas. Opportunistic Europeans, almost exclusively men, seized the chance to make a better life for themselves, usually in the hope of getting rich quick. These men were often the first colonists to advance inland. Once the Spanish had found fabulous mineral wealth in Mexico, the search for gold and silver was a common feature in the Americas until 1900. In Brazil, for instance, bands of gold hunters roamed the inland regions, becoming the first Europeans to do so. The French, Dutch, and Swedish built colonies in the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes regions to take advantage of the fur trade. Other sources of wealth abounded: Europeans viewed the land as theirs to colonize, and they used it to make money. Tobacco and, especially, sugar plantations became popular ways to make money from land. The Puritan colony in New England, meanwhile, based its prosperity upon the family farm.

Initially, most colonists in the Americas were men (the exception was New England, where families were more likely to settle as a unit). This gender imbalance had two main effects: first, in some colonies, such as New France, the population grew very slowly until a concerted government effort brought over more women. Second, in all cases, European men had children with Native women, creating sizeable mixed-race communities. Such mixed-ancestry children were often treated as inferior. The Métis of New France, for instance, often became outcasts from both European and Native American communities. Spanish colonial authorities also attempted to impose racial hierarchies that placed Spaniards at the top of a three-tiered society, with castas or mestizos (mixed-race) in the middle and native peoples and black Africans at the bottom.

The Spanish were the first European empire to colonize the Americas, which is one reason they had the largest, richest, and most populous empire. The Dutch who like the Spanish and the French ran sugar plantations in the Caribbean had the smallest presence. Their colony called New Netherland included parts of modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New England and only consisted of a few hundred settlers. English and Portuguese colonies were both prosperous, and they quickly outgrew their original boundaries. The French claimed the next largest landmass behind the Spanish, but it was almost exclusively focused on the fur trade, and it was thinly settled.

Religion and Philosophy

Religion was an integral part of the new settlements. This is perhaps to be expected, as many of the early settlements were established during the Reformation. The battle for souls that was raging in Europe extended to Africa, Asia, and the Americas as well.

The Spanish and Portuguese, who were the great naval powers of the fifteenth and 16th centuries, brought Catholic priests with them on many of their exploring, trading, and colonizing missions. Five major orders (the Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians, Mercedarians, and Jesuits) accompanied the Spanish colonizers. They attempted to convert as many native peoples as possible, and they were noted for the zeal of their efforts. The clergy could often be quite brutal, but some became noted for their willingness to stand up for native peoples, who they believed were being mistreated. The most famous example is Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican friar who wrote a stinging rebuke of Spanish colonization.

Like the Spanish and Portuguese, the French also brought priests and missionaries with them when they settled. The Recollet, Capuchin, and Jesuit orders of Catholic priests all sent missionaries to the new French colony in North America. The missionaries believed that the Native Americans needed to convert to Christianity and change their lifestyle. The priests quickly came to believe that the Native American’s nomadic lifestyle was uncivilized, and they proceeded to try to correct it. The Jesuits focused their efforts on the Huron, an ally of the French whose seminomadic ways seemed the most civilized out of all the tribes. While living amongst them, however, they also found aspects of Huron culture they appreciated. The Huron were sober (alcohol arrived with the Europeans), they lived healthily, respected different religions, and were generally open towards others. In the end, the French missionaries had mixed success in their attempts to convert the Native Americans to Christianity.

A painting of a Catholic priest, Father Jacques Marquette, preaching to Native Americans in present day upper Michigan (Source: Wikimedia)

In general, Native Americans considered the new religion carefully, and several tribes incorporated aspects of Christianity into their own religions. Others were converted entirely. Many, however, faked their conversion because the French only gave guns to Christian converts, and the Huron in particular were at war with another tribe, the Iroquois. Still others rejected Christianity entirely. Christian notions of heaven, hell, and sin often did not resonate with Native Americans. Moreover, the priests often brought European diseases like smallpox with them. When these decimated the local population, the priests became people of ill repute.

Female religious orders also accompanied the French. While nuns in Europe were expected to live in a cloister, in New France nuns could often live a more active religious lifestyle in the settlement. Female religious women played a major role in education in the colony, both of Native Americans and French immigrants. A few nuns also converted Native American girls.

Religion was also at the core of the Puritan settlement in New England. While the colony was said to be established in the name of religious freedom, in fact it was established so that the Puritans could practice freely; they were banned in England. All members of the community were expected to attend church, and dissenters were threatened with banishment. As generations passed, however, the Puritan’s religious fervor diminished somewhat, whereas the Catholic Church remained a strong presence in French and Spanish colonies. The English colonies made no sustained efforts to convert the Native Americans.

While bringing Christianity to the people they considered to be “heathen” was a major driving force of initial European colonization and exploration, the act of meeting other cultures also brought Europeans into contact with new ideas. For the most part, this contact occurred between the clergy and the peoples of Asia, Africa, and the Americas. While traders and settlers would also have been in contact with these cultures, they either did not take the pains to learn about them or did not keep records of their encounters. The clergy, however, spent a lot of time with different peoples in the attempt to convert them.