46 WORLD WAR I

|

Before you Begin to Read — Watch and Learn |

|

For an introduction to the changing world of the early 20th century, watch both of the following videos: Crash Course in European History, #30 Crash Course in European History #31

|

Causes of the First World War

The war plans of the European powers are often seen as one of the causes of the First World War. This is not simply because they existed; war plans tend to be contingent – they are made in case of a war, not out of a desire to start one. Nonetheless, the war plans of the European powers assumed startling influence in the months before and after the outbreak of the war. European leaders allowed their decisions to be dictated, to a certain degree, by their war plans. Moreover, the way the French and Germans wrote their plans showed that they believed that any war would be quick and decisive and won by offensive action. In this, they epitomized a widespread belief in Europe that it was possible to win an offensive war in a short period of time; British soldiers leaving for the front in August 1914, for instance, fully believed that they would return by Christmas. None of the European powers anticipated the trench-war stalemate that quickly developed in the first weeks of the war; no one realized that each side’s defensive capabilities were stronger than any offensive.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the causes of World War I and its significance for world history by watching Crash Course in World History #36. |

New Weapons of War

Both the Allies and the Central Powers entered the First World War with the strong, perhaps counterintuitive, belief that any war would be won using offensive tactics – in other words, a dashing attack. It became clear early in the war, however, that an offensive charge across no-man’s-land to enemy territory was ineffective, though, alarmingly, commanders proved willing to use this tactic even later in the war. In a charge, most soldiers were mowed down by enemy fire long before they reached the other trench. The trench war that developed on the Western front, however, showed both sides that they needed new tactics – and new technologies – to fit the situation.

A photograph of English soldiers assembled in a trench near Beaumont Hamel, Somme, in 1916 (Source: Wikimedia)

In many cases, existing technology was adapted to meet the new conditions. In other cases, new technologies were developed; the best example of this was the tank, which was developed specifically as an armored vehicle to move troops through no-man’s land. Armies sometimes proved slow to abandon old technologies. The bayonet, for instance, was the most widely issued weapon of the war, though soldiers used it mostly as a can opener or for toasting bread (by skewering it and holding it over the fire). It only proved useful in close combat. Armies that adopted new technologies sometimes proved remarkably successful as a result.

As armies on both sides eventually abandoned the headlong charge as a tactic, they established a better one: the creeping barrage. According to this system, the infantry would creep across no-man’s-land with protection from artillery, which would bombard the other side so that they could not fire back. Poison gas was used to incapacitate the enemy, and the resulting period of disorientation was used to storm the trenches. The tank helped to break the deadlock in the war by providing a useful solution to how to get across to the other trench. Finally, though airplanes were not as critical as they were in the Second World War, they were used to provide cover for an assault, or to attack enemy planes.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Arthur Empey was an American who served in the trenches during World War I. After the war, he published his recollections which included the following account of a poison gas attack: We had a new man at the periscope, on this afternoon in question; I was sitting on the fire step, cleaning my rifle, when he called out to me: ‘There’s a sort of greenish, yellow cloud rolling along the ground out in front, it’s coming — But I waited for no more, grabbing my bayonet, which was detached from the rifle, I gave the alarm by banging an empty shell case, which was hanging near the periscope… Gas travels quietly, so you must not lose any time; you generally have about eighteen or twenty seconds in which to adjust your gas helmet. A gas helmet is made of cloth, treated with chemicals. There are two windows, or glass eyes, in it, through which you can see. Inside there is a rubber-covered tube, which goes in the mouth. You breathe through your nose; the gas, passing through the cloth helmet, is neutralized by the action of the chemicals. The foul air is exhaled through the tube in the mouth, this tube being so constructed that it prevents the inhaling of the outside air or gas. One helmet is good for five hours of the strongest gas… German gas is heavier than air and soon fills the trenches and dugouts, where it has been known to lurk for two or three days, until the air is purified by means of large chemical sprayers. We had to work quickly, as Fritz (the Germans) generally follows the gas with an infantry attack. A company man on our right was too slow in getting on his helmet; he sank to the ground, clutching at his throat, and after a few spasmodic twistings, went West (died). It was horrible to see him die, but we were powerless to help him. In the corner of a traverse, a little, muddy cur dog, one of the company’s pets, was lying dead, with his two paws over his nose. You can read a longer excerpt of his account here. |

|

|

Click and Explore |

|

Soldiers in World War 1 were the first to be diagnosed with PTSD (called “shell shock” at the time). Read more about shell shock in a special report produced by the Smithsonian Magazine entitled, The Shock of War.

|

Effects of the First World War

To those who lived through it, the First World War was known as The Great War. It touched every life in those countries that fought. Many people had a relative who fought in the war; some, of course, had to deal with the death or maiming of loved ones. Europe was a shattered continent after the war ended; its economies were heavily in debt, large parts of northern France and Belgium were a ruined wasteland, and many people were imbued with a horror of modern conflict. This reality shadowed much of what happened in interwar Europe.

The legacy of the war also included numerous social changes. In particular, the multinational empires of eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East – the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and German Empires – were dissolved. Independent nation-states (and imperial mandates) stood in their place. As these new countries tried to survive on their own, they faced numerous growing pains. In particular, they sought to deal with the legacy of multiculturalism that the dissolved empires left behind. How could one create a strong Poland, for instance, when one-third of the new country’s population was not Polish?

Social Trauma

In many ways, the First World War was a collective trauma for European society. A whole generation of men was decimated; an estimated 16 million civilian personnel and soldiers died, and another 20 million were wounded. Many returned from war with psychological wounds that took years to heal. Some soldiers never recovered from the terrible experience of the war. Many soldiers returned home with varying degrees of shell shock, or what we know now as post-traumatic stress disorder. With only a rudimentary system of assistance available to these men, they were for the most part left to their own devices or to the care of their families.

For many people, the experience of war shattered any prewar illusions that war was glorious. Those soldiers who had lived in the muddy, rat-infested trenches often came to believe that war was to be avoided at all costs. This sentiment was expressed in many ways. On a societal and political level, the people of France and Britain in particular were eager to avoid another world war in the late 1930s, when German aggression made war seem more likely.

Many artists and writers also expressed their experiences of war in a variety of moving ways. All Quiet on the Western Front, by the German writer Erich Maria Remarque, perhaps best depicts the terrible conditions of the war and the arbitrariness of death for those who fought in it. Others felt motivated by their abhorrence for war to join pacifist societies or international organizations like the League of Nations that worked for peace.

Many who survived the war questioned the values that plunged the world into it. Patriotism seemed like an outdated notion, and many postwar artists questioned its value. This contrasted sharply with prewar modernism, which often embraced the purifying and strengthening qualities of violence and war. German painter Otto Dix was one of many to depict the horrors of war; Dix’s The Skat Players, for instance, shows three men playing cards while sporting a number of grotesque artificial limbs.

Stormtroopers Advancing Under Gas, etching and aquatint by Otto Dix, 1924 (Source: Wikimedia)

The trauma of the First World War on society is still remembered today in many countries. In France and Belgium, the two countries that endured the most destruction as a result of the war, November 11 is a holiday to commemorate those who suffered or died during the war. In the countries of the British Commonwealth, November 11 is commemorated with ceremonies at 11:00 a.m., the precise time when the armistice began in 1918. In the days leading up to this day of remembrance, many people wear a poppy in honor of those who have died in war – all wars, but particularly the First World War. Throughout the world, the sacrifices of those who gave their lives in the First World War is commemorated in many ways – on countless statues, in monuments in prominent places, in churches and schools, and of course, in myriad graveyards in France and Belgium. Since the end of the war, these commemorative events and monuments have been of great importance to those affected by the Great War.

Minorities

The legacy of the First World War was positive for many countries, especially those in eastern Europe that gained their independence as a result of the fall of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, German, and Ottoman Empires. In general, however, the countries of eastern and central Europe reflected the mixing of peoples throughout history in those regions. As massive multinational empires gave way to nation-states, those new states had to deal with high proportions of minorities. In Poland in 1919, for instance, an estimated one-third of the population was not Polish. Rather, that remainder comprised a mix of Ukrainian, Jewish, German, Lithuanian, and Czech nationals scattered across the country. The situation was much the same across eastern Europe.

At the Paris Peace Conference, the British, French, and Americans forced Minorities Treaties on the countries of eastern Europe. They also ensured that there was a mechanism for complaints about the treatment of minorities at the League of Nations. By doing this, they hoped to avoid situations like that in prewar Romania, which at its creation in 1879 assured democratic Britain and France that it would care for its Jewish minority. Instead, Romanian Jews were harassed and intimidated for decades while the Great Powers did nothing.

The existence of the Minorities Treaties may have satisfied the British, French, and Americans, but the treaties did little to improve the plight of minorities in the interwar period. The treaties themselves had started the process off badly, as the countries of eastern Europe were offended that these treaties were imposed upon them.

Discrimination against minorities took a slightly different form in each country. In Hungary, for instance, the people wanted revenge for the territory taken from them in the Treaty of Trianon. Many radical Hungarians decided that Jews were the reason for Hungary’s shame, so they took action against them. They harassed, intimidated, and isolated the Jews, enacting numerus clausus regulations, or quotas, on Jewish admittance to professional schools, including medical and law schools. The Polish government also enacted numerus clausus laws to limit Jewish attendance at universities, where many believed the Jews were usurping places from Polish students. The Polish government also carried out a heavy-handed policing effort against Ukrainians in the east. Ukraine, which had existed for more than a year after the war until Russia conquered it, had fought a bitter war against Poland during its short life. Ukrainians in eastern Poland continued the struggle in the late 1920s.

Of all the countries of eastern and central Europe, however, it was Germany that most often used the Minorities Treaties and the League of Nations to its advantage. After Germany was admitted to the league in 1926, it took great care in representing the interests of German nationals in other countries. This advocacy continued into the late 1930s, when the Nazis developed a great interest in the fate of the two million Germans living in Czechoslovakia. Once the Nazis had conquered all of Czechoslovakia, they began to wage an international propaganda campaign to raise awareness of the “plight” of German citizens living in Polish-controlled Danzig. Hitler hoped that the campaign would help him annex the region without provoking war with Britain and France, who had agreed to come to Poland’s defense in the Treaty of Versailles. Eventually, Hitler abandoned his diplomatic efforts and invaded Poland.

Women’s Suffrage

The women’s suffrage movement began before the First World War, but many of its successes can be traced to wartime promises and the debt that European states owed to their soldiers and soldiers’ families. It was also because of political calculations. Belgium was one of several countries where the first women who were permitted the vote were war widows. While symbolically this is a nice gesture to those who lost their husbands in the service of their country, governments also calculated that war widows were more likely to vote for them – presuming, sometimes incorrectly, that the women agreed with the war in which their husbands had fought.

Many of the new countries of Europe also introduced voting for women after the war, including Czechoslovakia and newly democratic Austria and Germany. In Poland, women were allowed to vote and stand for office; eight women were elected to parliament in the country’s first postwar election, in 1919.

Some European countries had introduced female suffrage at various points in their history. In eighteenth-century Sweden and Poland, some women were permitted to vote. In France, suffragettes were among the revolutionaries in the 1790s, though they were generally ignored. Women were allowed to vote in France during the brief Paris Commune of 1870–71, but when the Commune fell, the privilege was not reinstated. French women did not regain the right to vote until 1944.

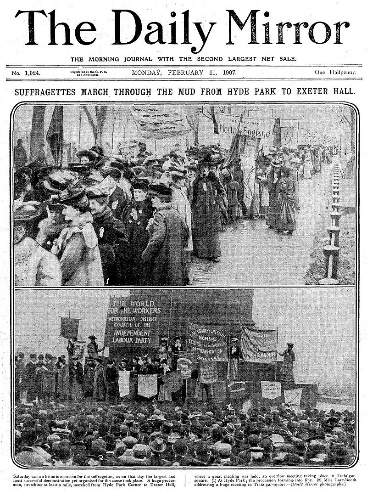

In Great Britain, the struggle for women’s suffrage gained increasing attention after the turn of the twentieth century. In 1907, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies held a march in London in favor of suffrage; 3000 women attended what was dubbed the “Mud March” because of the conditions. Shortly thereafter, some women split from the NUWSS and continued the quest for suffrage in more radical ways. In 1908, suffragettes attempted to storm the House of Commons, and in 1909 they set fire to the country home of prominent cabinet minister (and later prime minister) David Lloyd George, even though he favored women’s suffrage.

The front page of the Daily Mirror on February 11, 1907 shows pictures from the Mud March (Source: Wikimedia)

The campaign ceased during the war, however. In 1918, Prime Minister Lloyd George oversaw the passage of the Representation of the People Act, which granted the vote and the right to stand for office to qualifying women. Those who were permitted to vote were women who were over the age of 30 and had owned property for six months, or who were married to someone who met those property qualifications. This comprised about eight million women and made women more than 40% of the electorate. (The Representation of the People Act also gave the vote to all men 21 years of age and older. Before this, a man had to own property in order to vote, but it was considered unjust to deny the vote to those who had risked their lives for democracy in the war but were not property owners.) In 1928, Parliament passed a law granting women the same voting rights as men.