19 EUROPE

In the early 17th century, Europeans experienced a complex web of alliances, rivalries, and power struggles involving various nations, including the Spanish Empire, France, the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic, and England, among others, as they vied for dominance in politics, trade, and religion. Meanwhile, despite the powerful states’ focus on controlling various regions, smaller areas in southern Italy, Scandinavia, Scotland, and Auvergne continued to resist their influence, maintaining a degree of autonomy. However, these struggles came at a cost, draining resources and exacerbating the impact of food shortages that affected the entire continent. Furthermore, by 1648, Europe’s population had grown to an estimated 100-110 million, putting additional pressure on resources. This combination of population growth, war, and famine ultimately led to political instability, sparking rebellions and protests against heavy taxes and trade restrictions that further destabilized the region.

Europe enjoyed advantages over other regions, particularly in food production, with Europeans consuming large amounts of meat. Watermills played a crucial role in grinding grain and providing energy, while Europeans primarily depended on burning wood and charcoal for energy. Most buildings, machines, and tools, such as winepresses, plows, and pumps, were made of wood with few metal parts. Fortunately, Europe’s abundant forests supplied the necessary wood, although iron remained relatively scarce. Additionally, 17th-century Europe saw the rise of fashion trends, including wigs and later powdered wigs, which became popular despite initial resistance from the church.

By the late 17th century, some regions began moving towards more representative forms of government, though this change was gradual and not widespread. Trade routes shifted as connections between England and central European regions like Saxony, Bohemia, and Silesia became more significant. However, Europe’s population faced a decline due to ongoing wars, famines, and plagues, dropping to around 102 million by the early 18th century. This period was marked by significant changes in European politics, economy, and society.

The last quarter of the 17th century saw the establishment of responsible parliamentary government in some regions. By 1700, the north-south trade axis had swung almost 90 degrees and ran east-west from England to Saxony, Bohemia, and Silesia. Population growth at the end of the century was slowed by war, famine, and plague, leading to a decline in Europe’s population to around 102 million shortly after the turn of the century

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the effects of the Plague in 17th century Europe by reading the scholarly article, Plague in seventeenth-century Europe, by Guido Alfani. |

GREECE AND THE BALKANS

In the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire maintained its grip on Greece and most of the Balkans, a region in southeastern Europe encompassing countries like Bulgaria, Serbia, and Croatia. Despite Ottoman rule, Christian communities, led by the Greek and Serbian Orthodox churches, enjoyed a degree of autonomy. However, the region’s complex web of alliances and rivalries was evident in the many men from western Christian Balkans who fought as mercenaries for either Venice or the Ottomans.

As the Ottoman Empire’s diverse territories brought together Islamic, Christian, and Jewish communities, tensions often simmered beneath the surface. Meanwhile, commercial agriculture emerged as a vital sector, focusing on high-demand crops like cotton, tobacco, wheat, and corn. This shift sparked the growth of trade centers and markets, integrating the Balkans into the global economy. However, the abolition of the Janissary system in 1638 disrupted this fragile balance. By ending the recruitment of Christian boys, the Ottomans closed off a key pathway for social mobility and integration. This change exacerbated rural tensions, as landlords sought to consolidate power and control over land and resources. As the century drew to a close, the Balkans teetered on the brink of upheaval, with rising ethnic, religious, and economic tensions foreshadowing future conflicts.

ITALY

In 17th-century Italy, a power struggle unfolded as Italian princes and foreign European powers, like Spain and France, competed for control of the region. The devastating Plague of 1629-1631, which killed hundreds of thousands in northern Italy, further weakened the already fragile city-states. Many powerful families were decimated, leaving gaps in leadership. In Genoa, the number of nobles drastically declined, while in Venice, only a few patricians held influence.

Despite these challenges, Venice remained a thriving port city, with its strategic location boosting trade and foreign shipping. On the other hand, Genoa faced economic decline, losing Corsica and suffering from a collapse in credit. Florence, once a powerful city-state, became a shadow of its former self, with control concentrated in the hands of the Medici Grand Dukes.

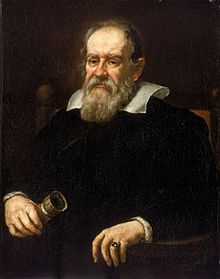

During these turbulent times, Italy still made important contributions to the Scientific Revolution. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), a renowned figure in astronomy, physics, and mathematics, was Italian. Another Italian, Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), made groundbreaking discoveries in anatomy, such as describing capillaries and other microscopic structures. His 25 years of work at the University of Bologna helped establish Italy as a center of intellectual progress.

A portrait of Galileo by Justus Sustermans, 1636 (Source: Wikimedia)

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Galileo’s Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of Tuscany, 1615 In 1615, Galileo sent a letter to Christina, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, in which he explains his scientific discoveries and argues that they do not contradict the teachings of the Bible or the Church. In the excerpts below, Galileo explains his understanding of the correct relationship between science and religion. Some years ago, as Your Serene Highness well knows, I discovered in the heavens many things that had not been seen before our own age. The novelty of these things, as well as some consequences which followed from them in contradiction to the physical notions commonly held among academic philosophers, stirred up against me no small number of professors-as if I had placed these things in the sky with my own hands in order to upset nature and overturn the sciences. They seemed to forget that the increase of known truths stimulates the investigation, establishment, and growth of the arts; not their diminution or destruction. … I think in the first place that it is very pious to say and prudent to affirm that the holy Bible can never speak untruth – whenever its true meaning is understood. But I believe nobody will deny that it is often very abstruse, and may say things which are quite different from what its bare words signify. Hence in expounding the Bible if one were always to confine oneself to the unadorned grammatical meaning, one might fall into error. Not only contradictions and propositions far from true might thus be made to appear in the Bible, but even grave heresies and follies. Thus it would be necessary to assign to God feet, hands and eyes, as well as corporeal and human affections, such as anger, repentance, hatred, and sometimes even the forgetting of` things past and ignorance of those to come. … It is necessary for the Bible, in order to be accommodated to the understanding of every man, to speak many things which appear to differ from the absolute truth so far as the bare meaning of the words is concerned. But Nature, on the other hand, is inexorable and immutable; she never transgresses the laws imposed upon her, or cares a whit whether her abstruse reasons and methods of operation are understandable to men. For that reason it appears that nothing physical which sense experience sets before our eyes, or which necessary demonstrations prove to us, ought to be called in question (much less condemned) upon the testimony of biblical passages which may have some different meaning beneath their words. For the Bible is not chained in every expression to conditions as strict as those which govern all physical effects; nor is God any less excellently revealed in Nature’s actions than in the sacred statements of the Bible. … From this I do not mean to infer that we need not have an extraordinary esteem for the passages of holy Scripture. On the contrary, having arrived at any certainties in physics, we ought to utilize these as the most appropriate aids in the true exposition of the Bible and in the investigation of those meanings which are necessarily contained therein, for these must be concordant with demonstrated truths. I should judge that the authority of the Bible was designed to persuade men of those articles and propositions which, surpassing all human reasoning could not be made credible by science, or by any other means than through the very mouth of the Holy Spirit. … You can read the full letter in the Modern History Sourcebook from which this excerpt was taken. |

|

CENTRAL EUROPE

The Holy Roman Empire, a loose confederation of seven German states, was still dominant in central Europe. Each state was governed by an elector and nominally subject to the Habsburg emperor, who was elected by the electors. This complex system created a delicate balance of power, with the Habsburgs seeking to maintain control over the various political units in Germany. The Habsburg Empire’s core consisted of the Archduchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Bohemia-Moravia, Silesia, the Kingdom of Hungary, and other Balkan territories seized from the Ottomans. Additionally, the Habsburgs claimed the Spanish throne and its European possessions.

The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) ravaged central Europe, causing widespread destruction and chaos. This brutal conflict involved guerrilla warfare, plunder, rape, and indiscriminate killing, with civilians often suffering more than soldiers. The war was fueled by a complex mix of religious, political, and dynastic motivations, including the Calvinists’ fight for recognition alongside Lutherans and Catholics. Mercenary generals also played a significant role, fighting for fame, power, and booty. The war became a series of bloody campaigns that engulfed much of Europe.

The war’s conclusion left the Habsburg Empire intact but severely impoverished. The territorial Lords emerged victorious, with Prussia rising as a strong state and Bavaria gaining territory. Most German cities lay in ruins, but Hamburg prospered due to its strategic location and trade connections. France and Sweden reaped significant benefits, with France gaining valuable cities and territories in Alsace, providing a strategic bridgehead into Germany. Sweden secured western Pomerania, Stettin, and key harbors, solidifying its control over northern Germany.

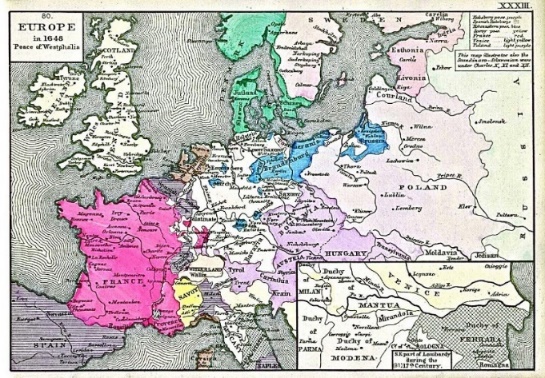

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) marked a significant turning point in European history, as the Habsburgs shifted their focus towards consolidating their power in the emerging Austro-Hungarian Empire. This led to a gradual separation between the destinies of Germany and Austria, with Germany embarking on its own distinct path of development. The treaty recognized the independence of Switzerland and the Netherlands, and established the principle of sovereignty, which would shape European politics for centuries to come. The legacy of the Thirty Years War continued to shape European politics, diplomacy, and culture for generations to come. The treaty’s impact was felt across Europe, setting the stage for the rise of new powers and the decline of old ones.

This map shows the boundaries of Europe in 1648 after the Treaty of Westphalia. (Source: Wikimedia)

GERMANY

In 17th-century Germany, there were early signs of economic and social change, but peasants largely remained under the control of local lords, with significant political and economic freedom only gradually emerging later. This slow process of emancipation did lay some groundwork for later developments, but the industrial revolution in Germany did not begin until the 19th century. As freedom of movement slowly increased, some peasants began relocating to urban areas, contributing to the labor pool for future industrial growth. The introduction of the potato in the 18th century, particularly in eastern Germany, significantly boosted food production, providing a more stable food supply that supported population growth and, eventually, industrialization.

Germany played a key role in the Scientific Revolution, with contributions from notable philosophers and scientists. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), a prominent philosopher, published work on infinitesimal calculus in 1684, shortly before Newton’s similar findings. Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) made important contributions to early scientific thought, although his use of the microscope and ideas about disease were more speculative and aligned with the pre-modern understanding of science. The establishment of the University of Halle in 1694 by Frederick III of Prussia further established Germany as a center of intellectual and cultural growth.

However, this period of progress was also marked by persecution, particularly of Jewish communities. The treatment of Jews in 17th-century Germany was harsh and often brutal, with violent expulsions, forced conversions, and severe restrictions on their rights. On August 22-23, 1614, over a thousand Jews were forcibly expelled from Frankfort, a stark reminder of the dangers and hardships faced by Jewish communities. Jews were often confined to ghettos, had limited economic opportunities, and faced forced conversions, making their existence precarious and fraught with danger.

AUSTRIA

In the 17th century, Austria was a central European power with a predominantly Catholic population, where the Jesuit order played a dominant role in shaping policy and education. At the heart of this empire was the Hofburg palace in Vienna, the seat of power for Emperor Leopold I (1640-1705). Leopold’s policy was rooted in the belief that the Habsburg rulers had been divinely appointed to the throne, with their authority stemming from God. However, the true source of his power lay in the military prowess of Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy, commander of the Imperial Army of Hungary. Under Prince Eugene’s leadership, Leopold’s forces achieved a decisive victory over the Ottomans in the Battle of Zenta in September 1697.

The Treaty of Carlowitz, signed in 1699, marked a significant milestone in the empire’s expansion. According to its terms, Hungary, with the exception of Croatia, was ceded to the Habsburg Empire, significantly bolstering its territorial holdings. This victory further solidified the Habsburgs’ dominance over the region, cementing their position as a major power in Europe. Prince Eugene’s military genius and Leopold’s strategic leadership had paid off, paving the way for further expansion and consolidation of the empire. The treaty also marked a turning point in the Ottoman-Habsburg conflict, as the Ottomans began to retreat from their European territories, leaving the Habsburgs as the dominant force in the region.

SPAIN

The Habsburgs, who ruled over a vast territory including Austria and Spain, played a crucial role in Spanish history. They ruled Spain from 1516 to 1700 through their Spanish line, with notable monarchs like Charles I (1500-1558) and Philip II (1527-1598), leaving a lasting legacy in Spanish politics, culture, and empire-building. The Habsburgs had a significant impact on Spanish politics, culture, and empire-building.

In 17th century Spain, social classes were fixed, and opportunities for advancement were limited. The Catholic Church exerted significant influence over daily life, providing spiritual guidance and comfort during important events. However, individuals who did not conform to Catholicism, including Jews and Muslims, faced persecution. Although the Inquisition’s power had begun to decline, its presence still impacted Spanish society. Women faced significant restrictions on their access to education and economic opportunities. Men from wealthy families held considerable power, while peasants and laborers struggled to make ends meet, engaging in subsistence farming, manual labor, and small-scale crafts. Meanwhile, a growing middle class of merchants and artisans began to emerge, laying the groundwork for future economic and social change.

During this period, the Spanish monarchy pursued ambitious policies, including involvement in the Eighty Years’ War against the Dutch and conflicts with England, driven by the interests of the ruling Habsburg dynasty and the Catholic Church. These efforts often led to costly military campaigns that drained Spanish resources. The Dutch West India Company’s blockades of Spanish shipping in the 1620s and 1630s further strained Spain’s economy by disrupting the flow of American silver and facilitating French and English settlements in the Caribbean.

The decline in Spain’s wool industry, coupled with broader economic troubles, contributed to Spain’s weakening position. By 1630, Spain faced increasing internal violence and revolt, compounded by devastating plagues between 1647 and 1654. The combination of economic mismanagement, military defeats, and inadequate governance led to a significant decline in Spanish power by the end of the century. The once-dominant empire struggled to maintain control over its vast territories, creating a power vacuum that allowed other European nations to rise and shape the complex geopolitical landscape of the 18th century.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

To learn more about the Spanish Empire’s rise and fall in the 16th and 17th centuries, watch Crash Course in World History #25. |

FRANCE

In the 17th century, France emerged as the dominant economic and military power in Europe, largely due to its population advantage. With twenty million people, France surpassed Spain, England, and Italy, which had significantly smaller populations. The Holy Roman Empire, despite having a comparable population, had been weakened by the Thirty Years War. France’s population growth enabled it to support a strong military and foster a thriving cultural scene.

This period, known as the Golden Age of France, saw significant contributions to the arts and sciences. Famous figures like Jean-Baptiste Moliere (1622-1673), artists, and scientists flourished, reflecting the era’s emphasis on intellectual and cultural pursuits. However, despite this focus on refinement and elegance, personal hygiene was surprisingly neglected. In fact, public baths became less popular due to fears of disease, and even at the king’s court, baths were taken only rarely, in cases of sickness. This contrast between cultural sophistication and personal neglect highlights the complexities of life in 17th century France. Meanwhile, the medical field advanced with the work of Charles-Francois Félix, who successfully operated on King Louis XIV (1638-1715), demonstrating the era’s capacity for innovation and progress.

The king’s support for the arts and sciences helped establish France as a center of culture and learning. Meanwhile, the French monarchy, particularly under Louis XIV, consolidated power and exemplified absolutism, a political theory developed from the belief that a centralized sovereign individual (i.e., the King) holds unlimited, complete power with no checks or balances from any other part of the nation or government. Louis XIV, the embodiment of absolutism, wielded unparalleled power, maintaining a massive standing army and transforming the Palace of Versailles into a royal palace. He expanded his authority by weakening the nobility’s influence in government, ensuring that the monarch held complete control. The French monarchy’s dominance during this period was unchallenged, with Louis XIV’s reign serving as a testament to the effectiveness of absolutism in concentrating power and fostering cultural and economic growth.

A painting of the Palace at Versailles by Pierre Patel, 1668 (Source: Wikimedia)

In May 1682, Versailles officially became the seat of government, marking a significant shift in French politics. Originally constructed as a hunting lodge and private retreat for King Louis XIII, Louis XIV transformed it into an opulent complex, showcasing his absolute power. The palace boasted 3000 mica-paned windows, 270 rooms, and 1500 jets of water from octagonal lakes, creating a breathtaking display of royal grandeur. Each year, approximately 4 million tulip bulbs were imported from the Netherlands, adding to the palace’s splendor. The Hall of Mirrors, with its stunning architecture, remains the most famous room in the palace, symbolizing the king’s authority and dominance.

Louis XIV’s relationship with the Protestant Huguenots, a minority group in France who followed Calvinism, was marked by shifting policies of tolerance and persecution. In 1681, Louis began intensifying efforts to pressure and persecute the Huguenots, but it was the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 that marked a major turning point. The Edict of Nantes, established in 1598, had granted the Huguenots significant rights and protections. By revoking this edict, Louis XIV effectively removed these protections, leading to widespread persecution of Huguenots. Many Huguenots were forced to feign conversion to Catholicism to avoid harsh consequences, while those who refused faced severe punishments, including torture. Thousands fled France, abandoning their homes and properties in search of refuge. Among the countries that offered sanctuary was Brandenburg, where the Elector Frederick William welcomed Huguenot refugees for economic and political reasons. Their arrival contributed significantly to the growth and development of Berlin.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green talk about King Louis XIV and his importance in 17th century Europe

|

THE NETHERLANDS AND BELGIUM

In 1648, Spain recognized the independence of the Dutch Republic, comprising seven provinces, including Holland, after a long struggle (1568-1648) tied to the Eighty Years’ War and the Thirty Years’ War. The Republic’s government, the States-General, represented each province, while an oligarchy of businessmen and the House of Orange controlled the army, leading to occasional clashes between the two ruling classes. Despite this, the country experienced remarkable prosperity and progress. The Dutch Republic’s strategic location and entrepreneurial spirit enabled it to thrive, becoming a major commercial power. Its independence marked the beginning of a golden age for the Netherlands.

Amsterdam emerged as the global financial and trade hub in the 17th century, surpassing Lisbon as the primary port for East Indies trade. The Dutch East India Company established control over key ports, including Batavia (1619), Ceylon (1638), the Cape of Good Hope (1652), and Sumatra (1667). By 1665, Dutch vessels dominated European maritime commerce, with 15,000 out of 20,000 ships flying the Dutch flag. The Dutch East India trade, particularly in pepper from the Spice Islands, fueled Amsterdam’s growth into the wealthiest city in the world. The city’s port became the busiest in Europe, with a vast array of industries, factories, and warehouses.

The Netherlands’ population reached two million in the second half of the century, supporting a large army and navy. The country’s fertile land and efficient agriculture enabled one farmer to feed two non-farmers, promoting commerce, industry, and shipping. The Dutch merchant fleet consisted of over 4,000 ships, and Amsterdam’s naval yards featured advanced machinery like mechanical saws and hydraulic wheels. The city’s Exchange Bank (established in 1609) facilitated trade, commerce, and finance, with a stock exchange and commodities market dealing in government stocks, company shares, and futures in goods like herring and wheat.

The tulip bulb became a highly sought-after commodity in the early 17th century, symbolizing status and wealth. Carolus Clusius introduced the flower from Turkey, and rare varieties sparked a speculative trade, with prices skyrocketing to 2,500 florins per bulb. Although the tulip mania eventually subsided, the flower remained significant in Dutch culture. The tulip trade exemplified the Dutch entrepreneurial spirit and the country’s emergence as a major economic power. Regulations and laws governing the trade demonstrated the need for structure in the face of speculative fervor.

|

Read about Tulip Mania in 17th Century Europe and its cautionary tale to modern investors and businesses. |

In the 17th century, the Netherlands offered a rare haven for Jews fleeing persecution in other parts of Europe. Sephardic Jews, who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal, found refuge in Amsterdam, where they established a thriving community. The Dutch Republic’s tolerant attitude and economic opportunities allowed Jews to practice their faith openly and engage in trade, commerce, and industry. Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel (1604-1657) and philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) were two prominent Jewish figures who contributed to the cultural and intellectual life of the Netherlands. By the mid-17th century, Amsterdam’s Jewish population had grown to around 10,000, making it one of the largest and most influential Jewish communities in Europe. Despite occasional tensions and restrictions, Jews in the Netherlands enjoyed relative freedom and prosperity, making the country a beacon of hope for Jewish communities elsewhere.

A painting of the interior of a Portuguese Jewish Synagogue by Emanuel de Witte, 1680. (Source: Wikimedia)

During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as Europe’s intellectual hub. René Descartes (1596-1650), a French philosopher and mathematician, flourished in Amsterdam, publishing his groundbreaking Discourse on Method in 1637. This work showcased his laws of refraction, philosophical ideas, and mathematical concepts. Meanwhile, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) pioneered the use of microscopes to study single-celled organisms. The country was also home to renowned artists like Rembrandt, Hals, Vermeer, and Ruisdael. Baruch Spinoza, a philosopher of Jewish-Spanish descent, was born in Amsterdam and made significant contributions to Western philosophy. Christian Huygens (1629-1695), a prominent scientist, developed the wave theory of light and invented the pendulum clock, earning him recognition as one of the greatest scientists of the era, second only to Newton. The Netherlands also boasted exceptional medical minds, including Franciscus Sylvius and Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738), who taught at Leiden University. The country’s cities were hotbeds of literary activity, with numerous publishers and bookshops. In fact, Amsterdam alone had over 400 bookstores, offering works in Latin, Greek, German, English, French, Hebrew, and Dutch.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Excerpts from Descartes’ Discourse on Method: In this book, Descartes advances his radical theory that the path to truth lies not in acceptance of what authorities teach but rather in the use of reason, as explained in the autobiographical excerpt below: Here the best lesson that I learned was not to believe too firmly anything of which I had learnt merely by example and custom; and thus I gradually extricated myself from the many errors powerful enough to darken our natural intelligence and diminish our ability to listen to reason. Finally, I resolved one day to make myself an object of study, and to employ all the powers of my mind in choosing the paths I ought to follow. … I observed that, while I was thus resolved to feign that everything was false, that it was absolutely that I, who thus thought, must necessarily exist. I observed that this truth I think, therefore I am was so firm and so assured that all the most extravagant suppositions of the skeptics were unable to shake it, I judged that I could unhesitatingly accept it as the first principle of the philosophy I was seeking. … Read a fuller excerpt of Descartes’ Discourse (from which the two paragraphs above were taken). |

|

The Art of Persuasion: How René Descartes Used Personal Doubts and Clarity to Convince His Audience

René Descartes used his method of systematic doubt to persuade others of his revolutionary ideas. In his influential book, Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes framed his philosophical exploration as a personal journey, inviting readers to follow his reasoning and have their own insights. By openly sharing his doubts and uncertainties, Descartes created a connection with his audience, making his conclusions feel more relatable and persuasive. His clear and straightforward language, combined with a focus on reason and personal observation, helped convince readers of the strength of his arguments. This approach teaches us that effective persuasion involves creating empathy, presenting ideas as a shared journey, and using clarity to engage and convince an audience.

GREAT BRITAIN

In the 17th century, the Kingdom of England underwent a significant transformation from an isolated island kingdom to a prominent European power. This shift was marked by a struggle between the English monarchy and Parliament, with monarchs seeking to extend their power by limiting Parliament’s authority. The English Parliament consisted of two houses: the Commons and the Lords. This struggle intensified during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth I, culminating in the death of James I in 1625. In response, Parliament issued the “Petition of Right” in 1628, citing the Magna Carta and establishing limitations on the king’s power.

The conflict escalated into a long Civil War, often referred to as the English Revolution of 1640-1688. Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) emerged as a key military leader, using religion as a rallying cry. His Puritan followers, known as “Round-heads,” opposed the king’s supporters, the “Cavaliers.” After executing Charles I, Cromwell established the Commonwealth of England in 1649. This period saw war with Spain and the destruction of the Spanish fleet.

A painting of Oliver Cromwell by Robert Walker, 1649 (Source: Wikimedia)

Following Cromwell’s death in 1658, the English experiment in republicanism ended, and Charles II (1630-1685) was restored to the throne. Under Charles II, military and naval power declined, and the Dutch navy regained supremacy. The accession of James II, a devout Catholic, in 1685 reignited the “King versus Parliament” tension. Parliament deposed James, and William III, a Protestant and ally of the Netherlands, assumed the throne with his wife Mary’s claim. During William’s reign (1688-1702), political battles raged between landowning Tories and merchant-class Whigs. Conflicts also arose between the English and Scots and between William’s supporters and those seeking to restore James to the throne. In 1692, an invasion fleet was destroyed by the British navy, securing William’s position. Despite an expanding economy, William’s reign was marked by constant political turmoil.

A painting of William of Orange by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1680s. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green discuss the English Civil War in Crash Course

|

In 17th century England, religion played a dominant role in shaping the lives of its people. The Church of England, established by Henry VIII, was the official state church, but its teachings were challenged by various Protestant denominations, such as the Puritans, who sought to purify the church of Catholic remnants. Many English people, influenced by Calvinist teachings, believed in predestination, fearing eternal damnation and seeking salvation through righteous living. Others, like the Quakers, emphasized personal spiritual experience and rejected formal rituals. The religious landscape was further complicated by the presence of Catholics, who faced persecution and struggled to maintain their faith.

During the 17th century, England became a hub for groundbreaking scientific discoveries, with several pioneers contributing to the Scientific Revolution. Key figures included Robert Boyle (1627-1691), a chemistry trailblazer; Robert Hooke (1635-1703), who refined the microscope; Edmond Halley (1656-1742), a renowned astronomer; Christopher Wren (1632-1723), a polymath excelling in geometry, astronomy, and architecture; and William Harvey (1578-1657), who first described the human circulatory system. Other notable scientists included Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689), who recognized the complexity of diseases, and Thomas Willis (1621-1675), who authored a comprehensive study of the nervous system, with his name still associated with a circle of arteries and a cranial nerve.

However, Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) stands out as the most influential English scientist. Building upon Galileo’s and Kepler’s work, Newton formulated the laws of gravity, developed calculus and the binomial theorem, and made significant strides in physics and astronomy. His impact was profound, leading to the Royal Society of London receiving a charter in 1662 to advance scientific knowledge. Many of the aforementioned scientists, along with literary luminaries like John Milton, John Dryden, and Edmund Waller, were members of this esteemed organization.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch Neil de Grasse Tyson explain why Sir Isaac Newton is the greatest physicist of all time.

|

Life in 17th-century England was grueling and monotonous for the average person. The country’s roads were often impassable due to mud, flooding, and lack of maintenance, making traveling a slow and arduous process. Carts crawled along at about two miles per hour, frequently delayed by adverse conditions. This isolation between regions ironically made inns crucial hubs of commerce. For instance, in 1686, the small town of Salisbury, Wiltshire, accommodated over 500 travelers and 800 horses in its inns. In London, transportation was mainly by boat on the Thames, as the narrow, filthy streets made carriage rides hazardous.

The city of London faced numerous challenges, including a devastating plague in 1665 that claimed an estimated 70,000 lives. The following year, a three-day fire ravaged most of London north of the Thames, leaving an estimated 200,000 people homeless. In response, the Corporation of London established a fire department, installed fireplugs, widened and straightened streets, and improved sanitation. However, as the plague subsided, typhus fever continued to be a significant health concern, and a severe measles epidemic struck in 1674.

IRELAND

Under James I (r. 1603–1625) and Charles I (r. 1625–1649), the English monarchy pursued policies that oppressed Irish Catholics, leading to a century of repression. James I promoted Protestant colonization in Ireland, and Charles I continued these policies, which intensified tensions. Charles I’s execution in 1649 by Oliver Cromwell marked a significant turning point. Cromwell, who sought to crush Catholic resistance and enforce British Protestant rule, launched a brutal campaign against the Irish from 1649 to 1652. This campaign involved severe violence and led to substantial loss of life and suffering among the Irish population.

Cromwell’s campaign was marked by extreme violence, resulting in significant loss of life and displacement, with estimates suggesting over 30,000 Irish fled to Europe. The war and subsequent policies led to a devastating decline in Ireland’s population, with estimates ranging from 20% to 30% loss. In the aftermath, the property and rights of Irish Catholics were largely appropriated by wealthy Protestant English and Irish nobles, leading to a profound shift in power dynamics and relegating Irish Catholics to secondary status. By the end of the century, the once-dominant Catholic population had been largely dispossessed, paving the way for centuries of sectarian tensions and conflict.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

On September 11, 1649, Cromwell and his army attacked the town of Drogheda. This was the first major military engagement of Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. The town of Drogheda was one of the best fortified towns. Cromwell, in attacking it, was determined to show the Irish that resisting the English army was futile. The end result of the attack was the defeat of the Irish. Over 2000 people were killed by the English army. In the following letter to John Bradshaw written on September 16, 1649, Cromwell discusses the battle and claims that it is sign of God’s blessing the English: It hath pleased God to bless our endeavours. After battery, we stormed it. The Enemy were about 3,000 strong in the Town. They made a stout resistance; and near 1,000 of our men being entered, the Enemy forced them out again. But God giving a new courage to our men, they attempted again, and entered; beating the Enemy from their defences. … Being thus entered, we refused them quarter; having, the day before, summoned the Town. I believe we put to the sword the whole number of the defendants. I do not think Thirty of the whole number escaped with their lives. … This hath been a marvellous great mercy. … I wish that all honest hearts may give the glory of this to God alone, to whom indeed the praise of this mercy belongs. Read the full text of Cromwell’s letter and other correspondence from the Irish campaign. |

|

DENMARK and NORWAY

In 17th-century Denmark, the nobility held significant power, living lavishly while many peasants had become dependent on them and struggled to survive. The country’s infrastructure suffered, with poor roads and heather overgrowth in fields. However, under King Christian IV (1588-1648), Copenhagen experienced growth, doubling in size and becoming a major hub with the construction of Europe’s largest naval arsenal and a new Stock Exchange. Christian IV’s reign saw continued conflict with Sweden and significant development efforts.

Denmark’s control over Norway, established in the 14th century, was reinforced by its larger population, more productive land, and strategic location. Unlike Norway, with only 5% cultivable land, Denmark had more arable land, allowing for greater economic growth. The Renaissance impacted Denmark, but its influence barely reached Norway, leaving it impoverished and thinly populated. Denmark imposed Protestantism on Norway, introduced Danish language Bibles and hymnals, and implemented initiatives like mining, new laws, and trading companies. In 1624, Christian IV founded the city of Oslo and renamed it “Christiana” after himself, a testament to his desire for legacy and control over the region. This renaming reflected the city’s new status as a Danish stronghold and a center of Protestantism in Norway.

SWEDEN

Sweden’s vast territory, stretching 1,000 miles north from its southern tip, is dotted with an astonishing 96,000 lakes. Despite its expansive geography, the country was sparsely populated in the 17th century, with around 1.1-1.2 million inhabitants. The Swedish economy relied heavily on the export of natural resources, with iron being the primary commodity, followed by silver and copper. The introduction of Flemish techniques in blast furnace construction and metal casting in the 1620s significantly contributed to Sweden’s iron industry growth, enabling the production of high-quality iron guns. This innovation swiftly propelled Sweden to dominance in the international cannon market, with the country becoming a major player in the global arms trade.

The catalyst for this transformation was Louis de Geer, a prominent entrepreneur and industrialist, who in 1620 brought Walloon iron workers to Sweden, importing expertise that would propel the country’s iron industry forward. The financing for the blast furnaces came from various sources, including the Swedish crown, Dutch investors, and English investors. The combination of natural resources, technological innovation, and strategic investment transformed Sweden’s economy and paved the way for its future prosperity. This period marked a significant turning point in Swedish history, as the country transitioned from a relatively insignificant player to a major force in European affairs.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green talk about developments in Central Europe and the Baltic region in the 17th century in Crash Course in European History #16 |

EASTERN EUROPEAN BORDERLANDS

The 17th century was marked by the continuation of the great struggle for the Baltic region (a geographic region located in Northern Europe, bordered by the Baltic Sea), begun in the 16th century, as Sweden, Russia, Poland, Brandenburg, and Denmark vied for political control. Poland, despite its vast size and population of around 8 million, was the weakest and most vulnerable of these states. Poland’s weakness was rooted in its diverse population, comprising different ethnic and religious groups, including Catholic Poles, Orthodox Lithuanians, Russians, Jews, and Germans, which hindered the formation of a cohesive identity and a united front against external threats. Additionally, the Cossacks, a fierce and semi-autonomous warrior caste present in both the Polish and the Ukrainian steppes, often challenged Polish authority and further destabilized the region.

In 1600, Sigismund III was recognized as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania by the Polish nobility, following the death of his father, Stephen Báthory. Seeking to take advantage of Russia’s weakness after the death of Tsar Boris Godunov, who had ruled Russia since 1598, Sigismund III invaded Russia in 1605. He captured Smolensk and briefly occupied Moscow before retreating. This invasion resulted in Polish possession of Smolensk and a significant influx of Polish culture into Russian life. However, Sigismund’s reign was marked by a series of disastrous wars, including a costly conflict with the Ottomans. Upon his death in 1632, his son Ladislaus IV succeeded him, bringing a measure of stability and tolerance.

This brief period of stability ended abruptly in 1648, when escalating tensions between the Polish government and the Cossacks culminated in a violent uprising. Led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Cossacks waged an armed insurrection, seeking increased autonomy and self-rule. To bolster their position against Polish dominance, the Cossacks turned to Orthodox Russia for support. Khmelnytsky pursued negotiations with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, aiming to secure military aid and greater autonomy. The resulting Treaty of Pereyaslav, signed in 1654, forged an alliance between the Cossacks and Russia, effectively placing Ukrainian Cossack territories under Russian control. In exchange for allegiance, Russia pledged military assistance, significantly altering the regional balance of power.

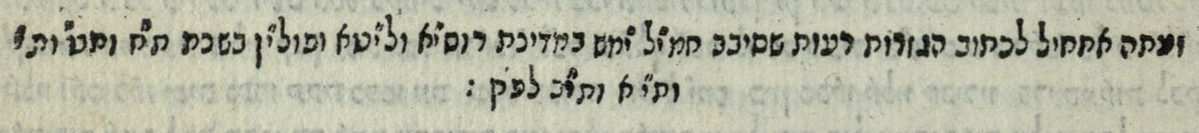

As a horrific echo of a dark European tradition, the Cossack uprising of 1648 unleashed devastating violence against Jewish communities, scapegoating them amidst the chaos. This tragic episode was part of a grim historical pattern, where Jews were habitually blamed and brutalized during times of turmoil. In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s Cossack forces targeted Jewish populations, slaughtering an estimated 35,000 Jews in Poland, Lithuania, and Russia, with thousands more taken captive or forced to flee their homes. The brutality was compounded by pogroms – state-sanctioned or tolerated riots and massacres – which razed Jewish communities, leaving destruction, trauma, and death in their wake. The Khmielnicki massacres, as they came to be known, had a lasting impact, eroding Jewish economic and cultural influence in the region, and forcing survivors to rebuild their lives elsewhere in Europe.

First edition of the Jewish account of the massacres by Yeven Mezulah (1653). The line in the picture reads, “I write of the Evil Decrees of Khmel(nytsky), may his name be obliterated…” (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch the short film, European Antisemitism from its Origins to the Holocaust, to learn more about the history of Antisemitism in Europe. |

RUSSIA

Russia in the early 17th century was a land of turmoil, plagued by power struggles, social unrest, and economic hardship. Amidst this chaos, Boris Godunov’s (1551-1605) ascension to the throne was marked by instability. As a non-royal, he faced opposition from aristocratic families like the Golitsyns, Shuiskys, and Romanovs. Compounding his struggles, crop failures between 1601 and 1603 led to devastating famines, and rumors swirled about his involvement in the assassination of the rightful heir, Dimitri. In 1604, a diverse army of Polish mercenaries, Cossacks, and discontented peasants marched on Moscow, challenging his rule. Following Boris’s death amidst this uprising, his son Feodore succeeded him, but violence from political, social, and religious factions persisted.

It wasn’t until 1613, when the National Assembly elected Michael Romanov as Tsar, that peace was finally restored, marking the beginning of a new dynasty. Under Michael’s leadership, Russia secured peace with Sweden through the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1618. The early Romanov rulers sought to minimize foreign influence, restricting foreigners to specific roles like drillmasters, armament makers, and fur traders, while confining them to segregated areas in Moscow and viewing them with suspicion. A new legal code was also formulated, codifying existing laws based on medieval absolutism and Orthodox Christianity.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the history of the Romanov Dynasty in the 17th century by watching this documentary produced by Maksim Bespalyi. |

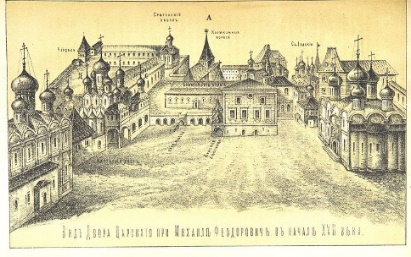

In the 17th century, Moscow was a vibrant and majestic city, renowned for its stunning architecture and rich cultural heritage. The city’s skyline was dominated by hundreds of gold-domed churches, with over sixteen hundred places of worship, including the iconic St. Basil’s Cathedral, which stood proudly in Red Square. This historic square was a bustling hub of activity, serving as a sprawling open-air marketplace where merchants and traders sold everything from fresh produce to exotic spices. Perched atop a hill, 125 feet above the Moscow River, the Kremlin fortress stood as a formidable stronghold, its walls ranging from twelve to sixteen feet thick and rising sixty-five feet above the surrounding rivers and moat. Within its sixty-nine-acre complex, the Kremlin housed the seat of Russian power, including the grand palaces, cathedrals, and government buildings that symbolized the country’s wealth and prestige.

A 19th century illustration of the Kremlin as it would have appeared in the 17th century. (Source: Wikimedia)

During the third quarter of the 17th century, Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich (1645-1676) carefully crafted an image of himself as a “holy ruler,” seeking to bolster his authority and legitimacy. As he neared the end of his reign, Russia’s population approached eight million, with the vast majority living in rural villages, forest clearings, or along rivers, rather than in larger towns. The most significant development of Alexis’ rule was the Great Schism of 1666, a profound religious rift that divided the Russian Orthodox Church. Patriarch Nikon’s attempts to reform the liturgy and rituals, aiming to restore what he believed were the authentic Orthodox practices, were fiercely opposed by traditionalists led by Archpriest Avvakum, who became the figurehead of the “Old Believers” movement. The brutal persecution of Old Believers, including Avvakum’s imprisonment, torture, and eventual execution by burning at the stake, sparked a wave of tragic events, as over 20,000 followers chose to immolate themselves in protest between 1684 and 1690.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

In this excerpt from Avvakum’s Autobiography, he describes his arrest and the treatment he received: Boris Neledinskij and his musketeers seized me during a vigil; about sixty people were taken with me. They were led off to a dungeon but me they put in the Patriarch’s Court for the night, in chains. When the sun had risen on the Sabbath, they put me in a cart and stretched out my arms and drove me from the Patriarch’s Court to the Andronikov Monastery, and there they tossed me in chains into a dark cell dug into the earth. I was locked up three days, and neither ate nor drank. Locked there in darkness I bowed down in my chains, maybe to the east, maybe to the west. No one came to me, only the mice and the cockroaches; the crickets chirped and there were fleas to spare. … In the morning the Archimandrite came with brethren and led me out; they scolded me: “Why don’t you submit to the Patriarch?” But I blasted and barked at him from Holy Writ. They took off the big chain and put on a small one, turned me over to a monk for a guard, and ordered me hauled into the church. By the church the they dragged at my hair and drummed on my sides; they jerked at my chain and spit in my eyes. God will forgive them in this age and that to come. It wasn’t their doing but cunning Satan’s. I was locked up there four weeks. Read a longer excerpt of the Autobiography (from which these examples were taken). |

|

Tsar Alexis’s untimely death at 47, likely due to a respiratory illness, led to a succession crisis. His ailing son Theodore took the throne, but his own demise six years later sparked further uncertainty. Theodore’s brother Ivan was next in line, but his physical disabilities rendered him unfit to rule. As a result, Alexis’s 10-year-old son Peter was crowned Tsar, with his mother Natalia serving as regent until he came of age.

However, Peter’s boyar supporters soon overthrew Natalia’s sister Sophia, who had taken on the regency role, and banished her to a convent when Peter turned 17. Peter’s reign officially began in 1694, at the age of 22. Eager to assert his authority and modernize Russia, Peter embarked on ” The Grand Embassy” – a diplomatic tour of western Europe. Disguising himself despite his towering height of 6’7″, Peter aimed to forge alliances against the Ottoman Empire, recognizing Russia’s limitations in confronting them alone. Additionally, he sought to educate himself about naval warfare, a crucial aspect of his vision for Russia’s future. Although his true identity was not entirely concealed, Peter’s incognito travels allowed him to observe and learn from European powers without being hindered by protocol.

A painting of Peter the Great studying the theory of shipbuilding in Amsterdam by an unknown artist. (Source: Russiapedia)

The Grand Embassy’s first prolonged stop was in the Netherlands, where Peter immersed himself in the shipbuilding industry, working and studying in the renowned yards of Zaandam and Amsterdam. During his time in the Netherlands, Peter met William of Orange, who was both King William III of England and Stadholder of the Netherlands. This encounter led to an invitation for Peter and a small entourage to visit England for four months, further broadening his exposure to Western culture and politics. Meanwhile, the remaining members of the embassy in the Netherlands successfully recruited over six hundred Dutch experts, including a Rear-Admiral, navy officers, seamen, engineers, and physicians, along with ten shiploads of equipment, to join them on their return to Russia. This influx of expertise and resources would prove instrumental in Peter’s subsequent modernization efforts.

Upon his return to Russia, Peter was resolute in his determination to transform the country into a modern, European-style state. He initiated a series of sweeping reforms, beginning with the abolition of traditional Russian attire, including the mandatory cutting off of beards and the adoption of Western clothing. Women were now required to wear petticoats, skirts, bonnets, and Western shoes, marking a significant departure from their customary dress. Additionally, Peter introduced the Julian calendar, replacing the old Russian calendar and aligning Russia with European timekeeping. He also founded St. Petersburg, a new capital city built on the Baltic Sea, which would serve as a symbol of Russia’s newfound connection to Europe and a hub for cultural and economic exchange. Furthermore, Peter reformed the Russian coinage system and introduced the “Order of St. Andrew,” a prestigious award bestowed upon individuals for their service to the state.

Peter’s reforms had far-reaching consequences, shaping the course of Russian history and leaving a lasting impact on the country’s culture and identity. While his efforts to modernize and Westernize Russia were ambitious and influential, they also came at a significant cost, displacing traditional ways of life and creating tension among those who felt their heritage was being erased. The construction of St. Petersburg and other projects relied heavily on the use of slave labor, with thousands of serfs and slaves toiling under brutal conditions to fuel Russia’s rapid expansion. As Peter continued to implement his reforms, he faced opposition from various factions, including the Orthodox Church and the old nobility, who saw his changes as a threat to their power and status. Peter’s legacy in Russian history remains complicated, marked by both visionary achievements and profound human costs.

Peter the Great: A Critical Examination of Intercultural Competency

Peter’s reign presents a complex example of intercultural competency. On one hand, he demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt to and adopt Western customs, technologies, and ideas, which enabled him to modernize Russia and integrate it into the European cultural and political sphere. He immersed himself in Western culture during his Grand Embassy, learned from European experts, and implemented reforms that transformed Russia’s architecture, art, and literature. However, his approach to intercultural exchange was also marked by a paternalistic and assimilationist attitude towards non-Russian cultures, including the forced adoption of Western customs and dress among the Russian nobility. Furthermore, his expansionist policies and use of slave labor to construct St. Petersburg and other projects raise questions about the ethics of cultural exchange and the exploitation of marginalized groups. Thus, Peter’s example highlights the importance of approaching intercultural exchange with sensitivity, respect, and a critical awareness of power dynamics.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about Peter the Great and other important European rulers of the 17th century in Crash Course in European History #17

|