36 AFRICA

The 19th century was a crucial time in African history, marked by significant changes in politics, economies, and cultures across the continent. African societies continued to evolve, building on their rich traditions while addressing internal challenges and engaging with external influences like the transatlantic slave trade and Islamic reform movements. Powerful kingdoms such as the Ashanti and Dahomey in West Africa, and ancient empires like Ethiopia and Egypt, navigated their own paths, through resistance, adaptation, or alliances with other powers. Internal developments, such as the rise of Islamic movements in West Africa and the expansion of the Zulu Kingdom in Southern Africa, played a key role in shaping the continent’s future. By the end of the century, African societies were laying the foundation for movements of cultural revitalization, self-determination, and anti-colonial resistance that would shape the 20th century.

NORTHEAST AFRICA

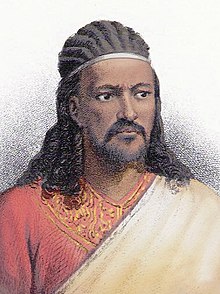

Ethiopia, the only state in Northeast Africa with a predominantly Christian population, faced significant internal and external challenges throughout the 19th century. Provincial warlords vied for power, undermining the emperor’s authority, while frequent conflicts with the Oromo people in the south posed a persistent threat. Amidst this turmoil, Emperor Tewodros II ascended to the throne in 1855, determined to unify and modernize Ethiopia. His initial efforts focused on centralizing authority, quelling regional rebellions, and establishing a professional standing army. Notably, Tewodros implemented key reforms, including tax code revisions and the founding of a national library, aimed at strengthening Ethiopia’s internal structure and bolstering its defenses against foreign encroachment.

A painting of Emperor Tewodros II who reigned from 1855-1868 (Source: Wikimedia)

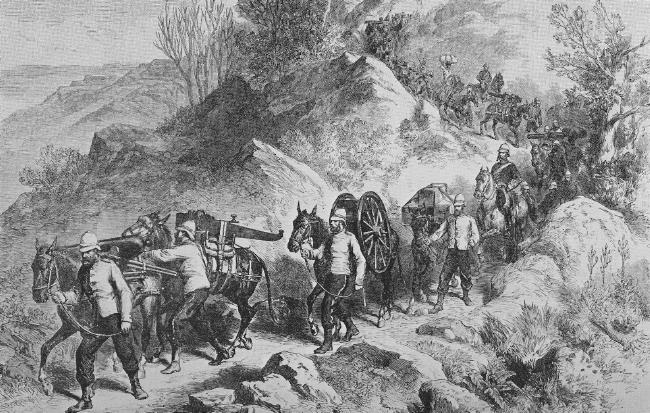

However, Tewodros’ ambitious agenda was hindered by ongoing Oromo conflicts and his struggles to secure international support. In 1862, he sought British military assistance, but when his appeals were rebuffed, he detained several British citizens in Ethiopia, prompting a British military intervention. The conflict culminated in the 1868 Battle of Magdala, where Tewodros suffered defeat and took his own life to avoid capture. His demise spawned a power vacuum, plunging Ethiopia into political instability.

An illustration from the Illustrated London News (1868) shows a victorious British army leaving Magdala (Source: Wikimedia)

Ultimately, Menelik II seized power in 1889, heralding a transformative era of modernization. Under his leadership, Ethiopia witnessed significant advancements, including railway construction, the establishment of Addis Ababa as the capital, and the expansion of educational institutions. Menelik’s visionary policies laid the groundwork for Ethiopia’s continued resilience and growth, cementing his legacy as a unifying force in Ethiopian history.

For ordinary Ethiopians in the 19th century, daily life was shaped by traditional social structures and economic realities. Women played vital roles in agriculture, trade, and domestic management, while men dominated the military, politics, and clergy. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church wielded significant influence, with many Ethiopians adhering to its teachings and participating in vibrant religious festivals. Occupations ranged from farming and herding to craftsmanship and commerce, with the majority of the population engaged in subsistence agriculture. Merchants and traders connected Ethiopia to regional markets, exchanging goods like coffee, textiles, and ivory. Rural communities remained largely self-sufficient, while urban centers like Gondar and Addis Ababa began to grow, driven by imperial patronage and trade.

The emergence of the Sultanates of Wadai and Darfur, which began to take shape in the early 19th century (around 1800), added complexity to the regional political landscape southeast of Egypt’s western border, between Lake Chad and the Nile River. To Egypt’s south, the Funj Sultanate of Sennar thrived along the Nile’s banks, asserting control over its territories since its establishment in the late 15th century (circa 1504) and lasting until its decline in the mid-19th century (around 1821). These Sultanates actively participated in trans-Saharan trade, exchanging goods like slaves, leather, and kola nuts for weapons, horses, and Islamic texts with merchants from North Africa, including Egypt. Strategically located along the Nile, the Funj Sultanate of Sennar maintained connections with Egypt, facilitating cultural and economic exchange. Egypt’s proximity to these Sultanates allowed for dynamic interactions, influencing regional politics, commerce, and Islamic scholarship. Through trade and diplomacy, Egypt’s rulers kept a watchful eye on these neighboring powers, recognizing their impact on regional stability.

After the decline of the Funj Sultanate of Sennar (present-day Sudan and southern Egypt) in the mid-19th century, the region experienced significant changes. The Funj Sultanate was eventually absorbed by the Egyptian Empire around 1821. This marked the beginning of Egyptian domination in the area, which continued throughout much of the 19th century. Egypt’s significant influence over the Horn of Africa, which includes countries like Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti, was largely due to Muhammad Ali, a visionary leader who transformed Egypt into a modern nation. After Napoleon Bonaparte’s brief invasion in 1798, Muhammad Ali seized power and became the Pasha of Egypt, consolidating control over Lower and Upper Egypt, Sudan, and parts of Arabia and the Levant.

Muhammad Ali implemented sweeping reforms to modernize Egypt’s military, economy, and culture. He promoted industrialization by cultivating cash crops like cotton and tobacco for export. The construction of Egypt’s first railway in 1854 marked the beginning of a transportation revolution, with over 1,000 miles of railroads by 1875. To establish a European-style military, Muhammad Ali sent promising citizens to study abroad and translated military manuals into Arabic. Muhammad Ali’s reforms also extended to education, governance, and infrastructure. He established factories to produce local materials and reduce reliance on imports, modernized Al-Azhar University, and built schools, canals, and irrigation systems. Additionally, he introduced democratic principles and convened an advisory council to guide his decision-making.

Muhammad Ali: A Model of Intercultural Competency in 19th-Century Egypt

Muhammad Ali, the 19th-century ruler of Egypt, exemplifies exceptional intercultural competency. He skillfully navigated the complex web of Ottoman, European, and African influences, blending Islamic traditions with Western practices to modernize Egypt. By sending Egyptians to study in Europe and inviting European experts to advise on reforms, Muhammad Ali fostered cross-cultural exchange and adaptation. His strategic alliances with British, French, and Ottoman leaders demonstrated an acute understanding of diverse cultural perspectives and interests. Through his visionary leadership, Muhammad Ali harmonized Egypt’s unique cultural heritage with international best practices, laying the groundwork for Egypt’s emergence as a modern nation. His ability to balance tradition with innovation, and local identity with global connectivity, makes him a compelling example of effective intercultural competency.

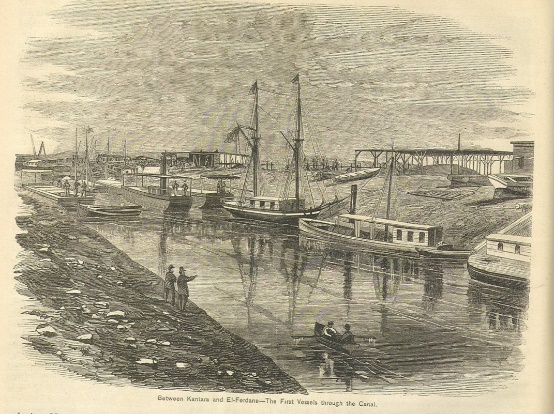

Muhammad Ali’s death in 1849 left a lasting legacy in Egypt, including a strong government, efficient army, and growing economy. His descendants ruled for another 150 years, during which time the country underwent significant transformations. The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 provided a vital maritime route, but European interests, particularly British and French, primarily operated it, despite being under Egyptian sovereignty. This led to tensions between Egypt and European powers, culminating in the British intervention in 1881-82, when Egyptians, led by Orabi Pasha, sought control over the canal. The British established dominance over Egypt, turning it into a protectorate, which marked the beginning of British rule in Egypt. By the end of the 19th century, Britain’s influence in Egypt had solidified, with British troops stationed in cities and towns, and British control over the Egyptian army, railways, and communications. This period, known as the “veiled protectorate,” lasted until 1914, when Britain declared a formal protectorate over Egypt, deposing the Khedive and replacing him with a Sultan of Egypt.

A pencil drawing of the Suez Canal in 1869 (Source: Wikimedia)

The British establishment of a protectorate over Egypt in the late 19th century significantly impacted ordinary Egyptians, leading to widespread economic exploitation and cultural displacement. As British control over the Egyptian economy intensified, peasants and workers faced increased taxation, forced labor, and displacement from their land. The British prioritized cotton production for export, leading to food shortages and economic hardship for many Egyptians. Urban centers like Cairo and Alexandria saw an influx of British expatriates, who dominated the economy and enjoyed privileges unavailable to Egyptians. Ordinary Egyptians faced restrictions on their movement, assembly, and expression, as the British imposed strict laws to maintain control. Additionally, the British undermined traditional Egyptian institutions, such as Islamic courts and schools, and promoted Western-style education and values. This led to cultural dislocation and erosion of Egyptian identity, as many Egyptians felt their customs and traditions were being suppressed. Overall, the British protectorate perpetuated inequality, poverty, and cultural disempowerment among ordinary Egyptians.

NORTH CENTRAL AND NORTHWEST AFRICA

In the 19th century, significant social, political, and economic developments occurred in North Central and Northwest Africa.. This region was characterized by powerful sultanates and empires, such as the Alawite dynasty in Morocco, which managed extensive trade networks and engaged in diplomatic relations with neighboring states. The large Berber population played a crucial role in these societies, contributing to trade, culture, and the resistance against external pressures. Local leaders also emerged to unify diverse ethnic groups under Islamic law, promoting trade and scholarship. Additionally, pastoralist communities maintained their traditional lifestyles, adapting to changing environmental conditions and inter-communal relationships. These dynamic societies laid the groundwork for the challenges and transformations that would arise as external forces began to encroach upon their territories.

This map shows the location of Algeria in Africa (Source: Wikimedia)

As the century progressed, the North African coast became increasingly divided between France and Britain. As Britain solidified its control over Egypt, France focused its imperial efforts on the western regions, particularly Algeria and Tunisia. Beginning in 1830, hundreds of thousands of southern Europeans, including many from France and Italy, settled in North Africa, dominating trade, industry, and finance. This influx generated significant resentment among North Africans, particularly in Algeria, where residents contested French claims to fishing rights. The French invasion of Algeria in 1830 marked the beginning of one of the largest and most destructive military campaigns in the narrative of European imperialism in Africa.

The French employed a combination of military might, political manipulation, and economic control in their imperial pursuits in North Africa. Initially, they launched large-scale military campaigns to conquer territories, often using overwhelming force to suppress local resistance. In Algeria, the French began with a brutal invasion in 1830, leading to significant urban warfare and the capture of key cities. Following military victories, they implemented policies of annexation, treating conquered areas as part of the French state. The French military also established a network of fortified outposts and garrisons to maintain control over newly acquired territories and quell any potential uprisings.

Simultaneously, the French sought to undermine local authority by exploiting existing rivalries among tribal and ethnic groups. They often co-opted local leaders or replaced them with pro-French officials, creating a structure that prioritized French interests. Economic control was also crucial; the French introduced land reforms that favored European settlers, leading to the displacement of local populations and their relegation to lower economic statuses. This displacement disrupted traditional ways of life, forcing many families into poverty and creating a sense of resentment toward the colonial authorities. Ordinary people often found themselves struggling to access basic resources and opportunities, as the settlers dominated trade and agriculture, particularly in cash crops like cotton and tobacco, which were exported to Europe. The combination of military conquest, political manipulation, and economic domination facilitated the French effort to establish and expand their colonial presence in North Africa, setting the stage for widespread resistance.

Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine (1808-1883) emerged as a key leader in the resistance against the French colonial invasion, successfully declaring independence for Algeria in 1837. An Islamic scholar and Sufi, he unexpectedly found himself leading a military campaign, rallying Algerian tribes to resist one of the most advanced armies in Europe. His commitment to what would now be called human rights, particularly towards his Christian adversaries, earned him widespread admiration, culminating in international honors for his efforts to protect the Christian community of Damascus during the 1860 massacre. However, after ten years of leadership, he was ultimately defeated by the French in 1847.

The Bridge Builder: Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine’s Legacy of Perspective Taking

Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine, an Algerian Islamic scholar and resistance leader, exemplifies remarkable perspective-taking in the face of colonialism and conflict. During the French conquest of Algeria in the 19th century, Abdelkader navigated complex cultural and religious divides to forge alliances and advocate for peaceful coexistence. Despite leading the resistance against French occupation, he demonstrated empathy and understanding towards European perspectives, recognizing the humanity shared by both sides. Abdelkader’s leadership was marked by tolerance, compassion, and openness, as evidenced by his protection of Christian captives and advocacy for interfaith dialogue. His willingness to engage with French intellectuals and politicians, while maintaining his commitment to Algerian independence, showcases his capacity for nuanced perspective-taking. Abdelkader’s legacy serves as a powerful model for cross-cultural understanding, encouraging us to consider multiple viewpoints and prioritize shared humanity in the face of conflict and division.

By the early 1850s, over 100,000 European settlers resided in Algeria, and the French had firmly established control. The catastrophic drought of 1867-68, compounded by locust infestations and cholera outbreaks, resulted in the deaths of over 300,000 people from a population of about 2.5 million. France also occupied Tunisia in 1881, provoking large-scale uprisings and sporadic warfare in the south. Morocco managed to resist European encroachment until the mid-19th century when France waged a successful military campaign, significantly increasing its influence in the region.

The Ottomans maintained control over Tripoli, Fezzan, and Cyrenica by 1835, positioning themselves as a significant imperial presence in North Africa amid the rising tide of European colonialism. During this time, Muhammad ibn Ali as-Sanussi (1787-1859) emerged as a mystical Muslim leader, successfully defending his people against Italian incursions and helping to preserve their independence. His resistance was emblematic of a broader struggle against encroaching imperial powers, highlighting the tension between local autonomy and foreign domination. Sanussi founded a spiritual movement that continued after his death in 1859 under the leadership of his son, Muhammed ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi. Additionally, missionaries from Libya played a significant role in spreading Islam throughout Northern Africa during this period, reinforcing local identities in the face of external threats and contributing to the complex interplay of religious and political dynamics in the region.

WESTERN AFRICA

In the 19th century, West Africa experienced significant political, social, and economic transformations driven largely by local dynamics. The Sokoto Caliphate, founded in 1804 by the Islamic scholar Usman dan Fodio, became one of the largest and most powerful states in the region, uniting diverse ethnic groups under Islamic law and promoting education and trade across its vast territory. Meanwhile, the Asante Empire in present-day Ghana reached its peak, controlling lucrative trade routes for gold and kola nuts. Farther west, the Fulani and Mandinka peoples also established influential states, with leaders like Samori Touré creating a vast empire in what is now Guinea, known for its resistance to external threats. These West African societies, rich in trade and cultural exchange, set the stage for both internal reforms and resistance as external pressures began to increase later in the century.

In the Niger River bend, the great African empires of previous centuries gave way to numerous smaller city-states, with Segu, Kaarta, and Masina emerging as significant centers of power and culture. These city-states played crucial roles in trade and the spread of Islam, fostering vibrant communities that engaged in commerce and scholarship. To the east, the Fulani, led by Usman dan Fodio, launched a series of military campaigns across Hausaland, which included the Kingdom of Bornu near Lake Chad. The Fulani possessed a formidable cavalry and, through their conquests, established the Bornu Empire under the Kanemi Dynasty. By the mid-19th century, this empire became the most extensive political structure in West Africa, encompassing approximately 150,000 square miles across twenty provinces, and facilitating the peaceful spread of Islam into central Africa.

The Ashanti Kingdom, which flourished from the 17th to the 20th century, was a powerful and influential empire that dominated much of modern-day Ghana in the 19th century. By 1850, it spanned approximately 125,000 square miles and housed around five million people. At its heart was the majestic capital, Kumasi, renowned for its opulent royal court. The Ashanti Empire’s unique succession system allowed the Queen Mother, such as Yaa Kyaa, who played a significant role in the mid-19th century, aided by senior chiefs, to select each new ruler, ensuring a seamless transfer of power.

However, the empire’s prosperity was tainted by its significant role in the transatlantic slave trade. Many Africans did not always view enslaved people as members of their own communities but rather as outsiders captured during wars or raids. This perspective was often influenced by the social structure of African societies, which were frequently organized around kinship ties; outsiders, including captives from rival groups, were seen as potential threats. By the early 1800s, the Ashanti Kingdom had become a major exporter of enslaved people, driven by the soaring demand in the Americas for labor. This trade was complex, with local dynamics influencing the capture and sale of individuals, often leading to significant social and political ramifications within their own societies. This lucrative trade brought luxury items and manufactured goods, including firearms, into the empire. Yet, it came at a devastating cost, fueling perpetual warfare from 1790 to 1896 as the Ashanti Empire expanded and defended its territories. The empire’s constant battles weakened its stance against the British, who eventually became its primary adversary. The Ashanti resisted British encroachment from 1823 to 1873, but ultimately, British forces invaded and briefly captured Kumasi in 1874. The Ashanti rebelled against British rule, only to be conquered again in 1896. Following another uprising in 1900, the British annexed the empire into their Gold Coast colony in 1902.

In the 19th century, Nigeria underwent significant transformations influenced by internal dynamics and external pressures. The region was home to powerful states, including the Oyo Empire and the Kingdom of Benin, which engaged in trade and warfare. The Fulani Jihad, led by Usman dan Fodio in the early 1800s, resulted in the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate, which unified various Hausa city-states under Islamic governance and promoted trade and education. As the demand for palm oil and other resources grew, European powers, particularly the British, intensified their interest in the region. They established trading posts and colonies, including Lagos in 1865, which became a crucial port for British trade. By the 1870s, the British had introduced fourteen steamers on the Niger River, facilitating trade and military operations. The British also expanded their influence by occupying Sierra Leone and gaining control over the Niger basin, establishing a strategic foothold in the region.

In the 1820s, a remarkable event shaped Western Africa’s future. Nearly 2,500 formerly enslaved individuals from the United States established Liberia, a nation founded by the American Colonization Society. The ACS believed African Americans would thrive in Africa, free from US oppression. Liberia declared independence on July 26, 1847. Between 1822 and the American Civil War, over 15,000 African Americans and 3,000 Afro-Caribbeans relocated to Liberia, bringing their culture and traditions. They modeled Liberia’s constitution and flag after the US. Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a wealthy free-born African American from Virginia, became Liberia’s first president on January 3, 1848.

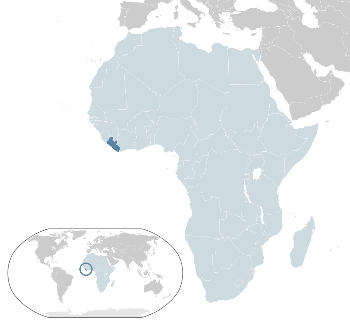

This map shows the location of Liberia in western Africa in dark blue (Source: Wikimedia)

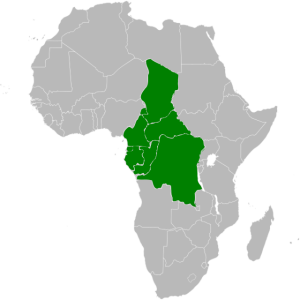

CENTRAL AFRICA

In the early 19th century, Central Africa flourished with diverse societies and cultures. Powerful kingdoms like the Kingdom of Kongo thrived, boasting extensive trade networks across the Atlantic and inland. These societies engaged in various economic activities, including agriculture, metallurgy, and trade in goods like ivory and palm oil. The Bantu-speaking peoples created vibrant communities with complex political structures and social systems based on kinship and trade. Islamic influence also spread in the late 18th century, fostering cultural exchanges and introducing new agricultural practices. Local leaders wielded considerable authority, navigating relationships with neighboring groups through diplomacy and warfare. This dynamic landscape of Central Africa, characterized by rich cultural heritage and social organization, would soon face significant disruption as European powers began their imperial pursuits.

In the mid-19th century, European powers began to penetrate central Africa with increasing intensity. One of the most notable explorers, Sir Henry Morton Stanley, navigated the Congo River for King Leopold II of Belgium, claiming vast territories for Belgium along the southern bank. His explorations led to the establishment of the Congo Free State, where Leopold exercised personal control, often with brutal consequences for the local populations.

Concurrently, France signed treaties with the Anziku Kingdom to secure the northern bank of the Congo, expanding its colonial ambitions in the region. These actions reflected a broader pattern of European imperialism, as various nations vied for control over African territories rich in resources. This competition for land intensified as European nations sought to expand their empires and exploit the continent’s wealth.

The scramble for Africa reached a critical turning point in November 1884 when Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian leader, organized the Berlin Conference. Fourteen European nations participated in this pivotal gathering, where they formalized their claims to African territories and effectively “divided” the continent among themselves. This conference marked the beginning of a more aggressive phase of colonial expansion, characterized by the establishment of artificial borders that disregarded existing ethnic and cultural boundaries. The decisions made at the Berlin Conference ushered in an era of intensified colonial activity, which systematically undermined African autonomy and self-governance. As a result, many indigenous communities faced displacement and disruption, leading to profound social and political changes across the continent. This colonial legacy continues to impact African nations to this day.

The onset of European imperialism in Central Africa in the 19th century had devastating consequences for the indigenous population. As European powers scrambled for control, local communities were forcibly displaced, enslaved, and subjected to brutal treatment. Additionally, European powers imposed artificial borders, disrupting traditional trade networks and cultural exchange, and imposed foreign systems of governance, education, and culture that eroded indigenous identities. The trauma and disruption inflicted upon Central African communities during this period continue to have lasting social, economic, and cultural impacts, perpetuating inequality and undermining development to this day.

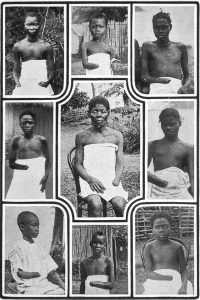

Belgium’s brutal colonial rule in the Congo exemplifies the devastating impact of European imperialism on Central Africa. Under the direct control of King Leopold II, it was infamous for its brutality and exploitation. Leopold’s regime, characterized by the ruthless extraction of natural resources like rubber and ivory, relied heavily on forced labor and terror tactics to maximize profits. The Congo Free State, established in 1885 as Leopold’s personal colony, operated outside of Belgian government oversight, allowing him to wield unchecked power. The Congolese were subjected to severe abuses, including forced labor, floggings, mutilations (such as the cutting off of hands), and mass killings for failing to meet rubber collection quotas or resisting colonial authority. Villages were destroyed, communities were enslaved, and displacement was widespread. Under the guise of “casual labor,” Congolese workers received little to no compensation, with violent repercussions for any form of dissent. The humanitarian crisis caused by Leopold’s exploitation resulted in an estimated 10 million deaths, primarily from violence, forced labor conditions, and disease. The horrors of Leopold’s rule left deep and lasting scars on the Congo, its people, and its post-colonial history.

EAST AFRICA AND THE GREAT LAKES AREA

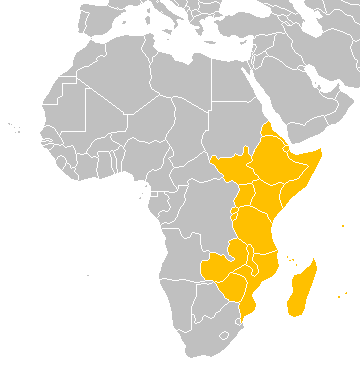

The 19th century was a transformative period for East Africa and the Great Lakes region. This vast and diverse territory was home to powerful kingdoms, such as Bunyoro, Buganda, Ankole, Karagwe, Rwanda, and Burundi, each with unique cultures, political structures, and economies. These kingdoms developed complex systems of governance and trade, engaging in alliances and conflicts that shaped the region’s history. For instance, Buganda’s influential king, Mutesa I (r. 1856-1884), maintained extensive trade networks with neighboring kingdoms and European explorers. Similarly, Rwabugiri of Rwanda (r. 1860-1895) expanded his kingdom’s borders through military conquests, solidifying his authority.

To the east, the Maasai people of central Kenya and Tanzania thrived as skilled pastoralists, raising cattle and adapting to the region’s arid landscape. Their expertise in cattle herding allowed them to sustain a strong economic presence, trading livestock and dairy products with neighboring communities. The Maasai developed a distinct culture characterized by iconic traditional attire, intricate beadwork, and rich oral traditions. Despite facing external pressures, they maintained their independence and cultural identity throughout the 19th century, although this way of life would soon be disrupted by European colonization and foreign administrative systems.

Meanwhile, the East African coast emerged as a hub of commercial activity, dominated by Arab traders who established themselves in key ports like Zanzibar and Mombasa. These traders profited from the ivory trade, which fueled economic growth but also led to widespread elephant poaching and habitat destruction. Additionally, Arab traders played a significant role in the slave trade, forcibly transporting many Africans to the Middle East and beyond. The arrival of European explorers, such as David Livingstone (1850s) and Henry Morton Stanley (1871), further paved the way for colonial expansion.

This map shows the region of East Africa in highlighted yellow (Source: Wikimedia)

As the 19th century drew to a close, East Africa and the Great Lakes region stood at the brink of significant change. European powers, particularly Britain, Germany, and Belgium, began asserting control over the area, dividing it into colonies and spheres of influence. This marked the beginning of a new era of colonialism, profoundly impacting the social, economic, and cultural fabric of the region. The legacy of 19th-century East Africa continues to shape the region’s identity and its relationships with the global community today, serving as a reminder of its rich cultural heritage and resilience in the face of external pressures.

SAVANNAH SOUTH OF THE CONGO BASIN

In the region that is now Zimbabwe, the Zulu wars led to significant upheaval, causing the displacement of many inhabitants and creating a power vacuum that the Ndebele people filled by the mid-1830s. The Ndebele, who migrated from the southern Zulu region, brought their own culture and traditions to the area, establishing a new socio-political structure. Meanwhile, on the western coast of Africa, the Portuguese had established settlements in what is now Angola. Following the abolition of the slave trade in the 1830s, these colonies began to decline, and the European population in Angola dwindled significantly. By 1850, only a few hundred Europeans remained. This marked the beginning of a more intense phase of European colonization across Africa.

As European powers partitioned Africa, local resistance grew increasingly fierce, especially after 1895. African communities faced direct taxation, forced labor systems, and land expropriation imposed by colonial governments. These oppressive measures led to prolonged and devastating conflicts. The consequences of colonialism disrupted traditional ways of life and caused widespread displacement. Many African leaders resisted European colonization, but few matched the success of Queen Manthatisi.

Queen Manthatisi ruled from 1815 to 1824 in what is now KwaZulu-Natal (modern-day South Africa). As regent for her young son, she exhibited remarkable military and political skill, earning her a reputation as one of the most formidable women leaders of the early 19th century. Her legacy extends beyond her military achievements, symbolizing the resilience and determination of African communities in the face of colonialism. Manthatisi’s impact on African history serves as a powerful reminder of the continent’s rich cultural heritage and the enduring spirit of its people.

.

The section in red shows the location of the region of KwaZulu-Natal in southeast Africa (Source: Wikimedia)

THE CAPE AREA

Southern Africa, particularly the region surrounding the Cape of Good Hope, was a culturally rich and diverse territory in the 19th century. Before European colonization, various indigenous groups had inhabited this land for centuries, developing complex societies and traditions. The Khoikhoi and San peoples, the original inhabitants of the area, lived off the land as pastoralists and hunter-gatherers. In addition to these groups, Bantu-speaking peoples, including the Sotho, Tswana, Swazi, Zulu, Pondo, Tembu, and Xhosa, migrated from central Africa, bringing with them distinct languages, customs, and social structures. These African communities established their own systems of governance, agriculture, and trade, forging a vibrant cultural landscape that would soon face disruption from European colonization.

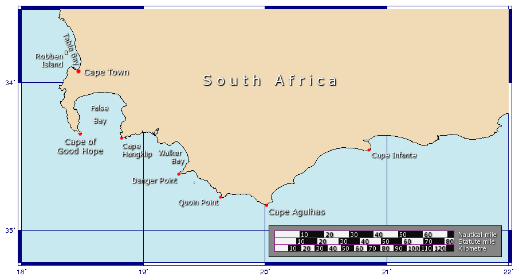

A map of South Africa showing the location of Cape Town and the Cape of Good Hope (Source: Wikimedia)

As the late 1700s approached, both the Dutch and British began establishing settlements near the Cape of Good Hope. With the dawn of the 19th century, the previously described migration of Bantu-speaking tribes, such as the Swazi, Zulu, Pondo, Tembu, Xhosa, Sotho, and Tswana, southward from central Africa sparked conflicts with the Dutch, particularly over cattle raiding along the Fish River. These hostilities led to prolonged tensions throughout the century. In 1814, the British gained control of Cape Colony through a treaty with the Dutch Republic, seeking to solidify their influence in the region. To further this aim, they built settler communities along the Fish River, prompting over 5,000 British emigrants to relocate to South Africa between 1820 and 1821. Consequently, English gradually supplanted Dutch as the official language, while the judicial system and currency underwent Anglicization. This marked the beginning of British dominance in the region, fundamentally shaping the trajectory of South African history.

Tensions escalated between the Dutch and English as Dutch settlers, known as Boers, steadfastly maintained their cultural identity and institutions. Seeking autonomy, the Boers embarked on the “Great Trek” in 1835, a mass migration of approximately 5,000 settlers who traveled up to 1,000 miles inland from the Cape to escape British control. As they traversed the region, conflicts arose with indigenous African populations whose land they crossed, particularly the Zulu, who fiercely defended their territory under the leadership of King Dingane. The Boers’ establishment of independent republics, such as the Natalia Republic and later the Orange Free State and Transvaal, further deepened tensions with both African kingdoms and the British. These rivalries set the stage for protracted conflicts, including the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and the subsequent Anglo-Boer Wars, which would shape the region’s political landscape for decades.

A photograph of a traveling Boer family from the late 19th century (Source: Wikimedia)

The discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa in the 19th century had far-reaching consequences for the region’s history. In 1867, diamonds were unearthed in an old volcano chimney along the Vaal River and near present-day Kimberley, straddling English and Boer territories. Within a decade, $100 million worth of diamonds had been extracted, drawing entrepreneurs and speculators to the area. The British swiftly annexed the Kimberley region into the English Cape Colony in 1870. Two Englishmen, Cecil John Rhodes and Barney Barnato, dominated the diamond trade, accumulating vast fortunes. The subsequent discovery of gold in 1886 sparked a massive influx of prospectors, with over 100,000 men seeking fortune by 1900. By 1911, Johannesburg, initially a humble mining camp, had swelled to a city of 237,000 inhabitants.

The diamond and gold rush set the stage for conflict between the Dutch and English. The Boer Wars, also known as the Wars for Independence, erupted in 1899, pitting the British against the Dutch. Although leaders on both sides framed the conflict as a “white man’s war,” Africans played a crucial role, suffering greatly in the process. Initially employed in non-combatant roles, Africans were eventually enlisted into the British Army, numbering nearly 30,000 by war’s end. The British victory had lasting repercussions, devastating the Boers economically and psychologically. In response, they forged a distinct identity as white Africans, or Afrikaners, driven by aggressive nationalism and a desire for self-determination.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about Nationalism in the 19th century by watching Crash Course in World History #34.

|

The impact of European imperialism on 19th-century Black South Africans was both devastating and long-lasting. Africans faced widespread displacement from their ancestral lands as European settlers, particularly the British and Boers, claimed vast territories for themselves. The treaties and agreements forged between these colonial powers, such as the peace established between Great Britain and the Boers, disregarded African rights and autonomy, leaving them marginalized in their own land. As Africans were forced into labor systems controlled by Europeans, many were subjected to harsh working conditions, particularly in the mining and agricultural sectors. Poverty and urbanization increased dramatically, as displaced Africans moved to cities in search of work, often finding themselves in overcrowded, impoverished conditions. The erosion of traditional African social structures and the loss of land set the stage for decades of economic exploitation and racial inequality under the emerging colonial regime.