20 THE AMERICAS

In the early 17th century, northern Europeans, already experienced in smuggling and raiding Spanish-American shipping, began to establish permanent colonies of their own in America. The north Europeans’ advantages included their access to the sources of shipbuilding material (particularly around the Baltic), fewer political commitments, diversified interests, and finally a more sophisticated device for obtaining capital and spreading risks – the chartered joint-stock company.

CANADA AND THE FAR NORTH

At the death of Champlain in 1635, Canada was the property of a joint-stock company, the Hundred Associates. Settlement advanced very slowly, however, and, by 1643, a year after a stronghold had been built at Montreal, there were less than 300 Frenchmen in all New France, exclusive of Nova Scotia. Even by 1665, Quebec contained only 70 houses and 550 people. The French fur traders, however, soon carried their commerce 2,000 miles inland. In 1685, the governor of Canada wrote to Louis XIV complaining that the colonial French had not civilized the Indians, but, on the contrary, the Frenchmen who lived among those he considered to be savages themselves became “savages.”

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Excerpts from Champlain’s Chronicles: Champlain chronicled his explorations and observations of New France in several volumes. In the following passage, he describes a battle between the native peoples with whom he was allied and the Iroquois. Notice that he calls the Algonquian and Hurons “our Indians.” As soon as we landed, our Indians began to run some two hundred yards towards their enemies, who stood firm and had not yet noticed my white companions who went off into the woods with some Indians. Our Indians began to call to me with loud cries; and to make way for me they divided into two groups, and put me ahead some twenty yards, and I marched on until I was within some thirty yards of the enemy, who as soon as they caught sight of me halted and gazed at me and I at them. When I saw them make a move to draw their bows upon us, I took aim with my arquebus and shot straight at one of the three chiefs, and with this shot two fell to the ground and one of their companions was wounded who died thereof a little later. I had put four bullets into my arquebus. As soon as our people saw this shot so favorable for them, they began to shout so loudly that one could not have heard it thunder, and meanwhile the arrows flew thick on both sides. The Iroquois were much astonished that two men should have been killed so quickly, although they were provided with shields made of cotton thread woven together and wood, which were proof against their arrows. This frightened them greatly. As I was reloading my arquebus, one of my companions fired a shot from within the woods, which astonished them again so much that, seeing their chiefs dead, they lost courage and took to flight, abandoning the field and their fort, and fleeing into the depth of the forest, whither I pursued them and laid low still more of them. Our Indians also killed several and took ten or twelve prisoners. The remainder fled with the wounded. Of our Indians fifteen or six-teen were wounded with arrows, but these were quickly healed. Read the full account of the battle (from which these examples were taken). |

|

Throughout the entire first two-thirds of the 17th century, New France continued to fight the Five Nations of the Iroquois League. In 1665, the Marquis Alexandre de Tracy arrived with 800 soldiers to wage a total war campaign against the Iroquois, killing and burning their fields and villages. The new military regime was absolute, with severe laws stringently enforced by torture, when necessary.

The first commercial venture into the Hudson Bay area was in 1668 when Fort Charles was built by Scottish entrepreneurs. Two years later, the Hudson Bay Company was chartered with title to nearly one and a half million square miles of territory. The French and English fought minor skirmishes in this region over control of the land and its furs for the next hundred years.

The French reliance on the fur trade with native peoples is of special importance. In 17th century world history, furs joined silver, silk, and spices as major items of global commerce. Of course, furs had long been used by people living in cold climates as a way of keeping warm, but the discovery of the Americas by Europeans and its integration into the larger political and economic world increased their significance. Several factors contributed to the rising importance of furs from the Americas. First, the Little Ice age caused a drop in temperatures resulting in harsh (and long) winters. Secondly, the dramatic increase in population in 16th century Europe required more acreage to be converted to farmland. This in turn decreased the habitat of fur-bearing animals (such as beaver, rabbits, sable, marten, and deer), thus reducing their population. Finally, the fashion world of the 17th century made prominent use of fur as a distinguishing mark of wealth and status – especially beaver fur hats for men. These factors created a growing demand for fur which pushed prices higher. Rising prices incentivized European traders to invest time and energy in the fur trade.

The French were the first to tap into this market. But they were followed quickly by both the English and the Dutch. All three relied on native peoples to bring the furs and skins to them. European merchants paid for the furs and skins with a variety of items, including guns, blankets, metal tools and cookware, and alcohol. This exchange had dramatic consequences. The environmental price was high. By the beginning of the 19th century, the beaver had been trapped almost to extinction. Since beavers played a critical role in maintaining a balanced ecosystem, their growing absence resulted in the loss and/or degradation of many wetland habitats. Native Americans were impacted by the trade as well. As they adapted to the use of European metal instruments, many of the skills used in the production of stone tools and cookware were lost. Native peoples, who did not possess knowledge of how to make metal tools and weapons, thus became increasingly dependent on European goods. As the number of beavers fell, tribes which had lived in peace began to compete against each other for access to an increasingly scarce resource. Armed now with rifles, the competition frequently erupted into violent clashes. Native Americans also found themselves increasingly drawn into conflicts between Europeans who were competing with each other for control of the trade. Finally, and most significantly from the standpoint of native peoples, by being drawn into extensive trading relations with Europeans they were increasingly exposed to diseases for which they had no immunity. The tragic story begun in the 16th century was thus continued in the 17th as hundreds of thousands of indigenous peoples died.

THE UNITED STATES

A large number of indigenous people groups lived in what is now the northeast United States and southeast Canada, including the Mi’kmaq, Wabanaki, Innu, Abenaki, Massachusett, Penobscot, Wampanoag, and the Delaware. The original name for the Delawares was “Lenape” and there is some evidence that they may have had limited contact with the Dutch as early as 1609. Squeezed between the New York state Iroquois League, the Susquehannock, and the more southern Powhatan Confederacy, a number of Lenape moved west but some stayed where they were increasingly forced to become dependent on and adapt to the cultural demands of European settlers. Native peoples living in this region of North America used little cylinders cut from blue or violet seashells threaded on a string as money called “wampum.” The early history of the Shawnee is not known with certainty, but they considered the Delaware people their “grandfathers.” By 1650, they were living in what is now southern Ohio and northern Kentucky. The Potowatami, Menominee, Cree, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Arapaho, Blackfoot, and Cheyenne peoples lived in what is now the upper Midwest.

Early Spanish, French, and English colonists in southeastern United States encountered a fifty-settlement confederation of the Creek Indian Confederacy in an area now consisting of Alabama and Georgia. The confederacy included various peoples with several languages, including Chickasaw and Choctaw. To the north of the Creek also lived the Cherokees where approximately sixty thousand lived in a hundred well-established settlements. The Natchez lived on the lower Mississippi. Many of the coastal Indians relied heavily on the sea, eating mollusks, and catching fish with spears. Native peoples had also perfected crafts such as basket-making, carpentry, woodworking, pipe-making, weaving, pottery, tanning, and even certain kinds of metal work. Tobacco cultivation created a demand for pipes, some finely wrought from clay and decorated.

ENGLISH SETTLEMENTS IN NEW ENGLAND

The area called “New England” included the colonies of New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. By 1700, there were 130,000 English settlers in this geographical area, with 7,000 in Boston and 2,600 in Newport. The first Englishman to explore the New England area was Bartholomew Gosnold, who sailed from the Azores in 1602 along the coast from Maine to Cape Cod. He built a house on Cuttyhunk, traded with native peoples, and introduced smallpox to the continent. By 1617, an epidemic of this disease reduced the indigenous population by as many as ten thousand.

Some Puritan separatists, who had first fled to the Netherlands to escape persecution, came to the Americas under the leadership of William Brewster and accompanied by William Bradford. They founded a colony in Plymouth in 1620. They set up their own self-government under the Mayflower Compact. In their first winter, over fifty percent of the settlers died of scurvy or general debility. After the first few seasons, William Bradford became their governor.

More English Puritans followed in the 1630s. The group was led by John Winthrop. They first sailed in March 1630 with 500 men, women, and children. After arriving, they raised cattle, Indian corn, and vegetables and soon developed both a fur trade and cod fishing. This colony was at once a theocracy and an oligarchy, yet it adopted trial by jury, freedom from self-incrimination, and levied no taxes on those who could not vote. However, there was no religious tolerance for those who practiced a form of religion different than that followed by the Puritans. Baptists and Quakers were considered to be the Devil’s agents. By the penal law of the colony, any Catholic priest, who reappeared there after having once been driven out, was subject to death. The Puritan migrations continued until 1637 when the English Puritans decided to stay and contest their fate in England, itself, as its Civil War started.

In 1634, Massachusetts joined with her neighboring Puritan colonies to form the New England Confederation. This was a loose union formed to settle boundary disputes and give mutual protection from Indians and both French and Dutch settlers. Free public education was soon established, a printing press appeared in Cambridge in 1639, and Harvard University was established in the same city in 1650.

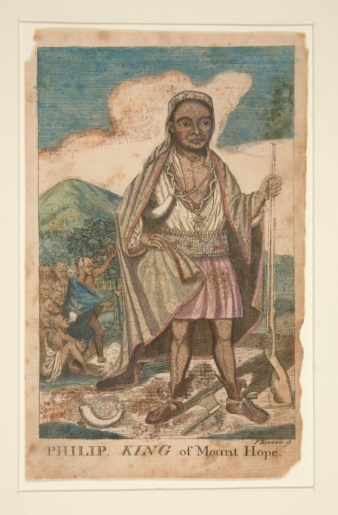

In 1675, conflict between English settlers and native peoples erupted in the so-called King Philip’s War. Metacom, chief of the Wampanoag who was called King Philip by the English, was one of the original friends of the early settlers. As, however, the relationship between native peoples and the Puritans soured, war broke out with Philip’s Wampanoag and their allies, the Nipmuck, opposing the English settlers. The Indians were not organized and had only hit and run tactics. The Narragansett tribe on the Bay sheltered some of the Indian refugees, giving Winslow the excuse to attack them with 1,000 men and finally winning in the most violent battle ever fought on New England soil. Philip was killed in August 1676 and most of his tribe were captured. The women and children were used as house servants and the men were shipped to the West Indies as enslaved people.

A line engraving of King Philip (Metacom), hand colored, by Paul Revere. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Click and Explore |

|

Read more about the history of King Philip’s War at the Pilgrim Hall Museum website. To learn more about the grievances of the native peoples against the English, read Metacom (King Philip’s) explanation at the History Matters website.

|

ENGLISH SETTLEMENTS IN THE MIDDLE COLONIES

This region included present-day New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, along with the small area of Delaware. By 1700, there were approximately 65,000 English settlers living in these colonies. By 1629, the Dutch had settled New Amsterdam. In 1644, as a byproduct of a Dutch-English War, the Duke of York claimed the area and renamed it New York. The Duke of York originally gave New Jersey as a gift to two friends, George Carteret and Lord John Berkeley. Philip Carteret, cousin of Sir George, emigrated from England to take possession in 1665. William Penn received a charter for Pennsylvania from King Charles II in 1681 and brought over Quaker dissidents from England, Wales, the Netherlands, and France. Penn established the city of Philadelphia in 1682, where some Swedes and Finns were already settled. Germans of the Mennonite sect soon also arrived and settled, so that by 1700, Philadelphia had outstripped New York City and soon rivalled Boston as an important English cultural center.

The Birth of Pennsylvania was painted by Jean Ferris in the 19th century. William Penn, holding the charter for Pennsylvania, stands and faces King Charles II, in the King’s breakfast chamber. (Source: Wikimedia)

ENGLISH SETTLEMENTS IN VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND

The first English settlement in the United States was established at Jamestown (Virginia) in 1607. Of the initial group, consisting of 104 men and boys, 51 died of disease and starvation within 6 months. Help from Indians and the arrival of a supply ship saved the rest. That ship also brought two women and five Poles, who had been recruited to begin the production of pitch, tar, and turpentine. Between the years 1616 and 1624, Virginia evolved from a trading post to a more financially prosperous permanent community. The planting and harvesting of tobacco was the key reason. As early as 1618, Virginia was exporting fifty-thousand pounds and more. In 1624, Virginia was designated a crown colony with a royal governor and operating council appointed by the king.

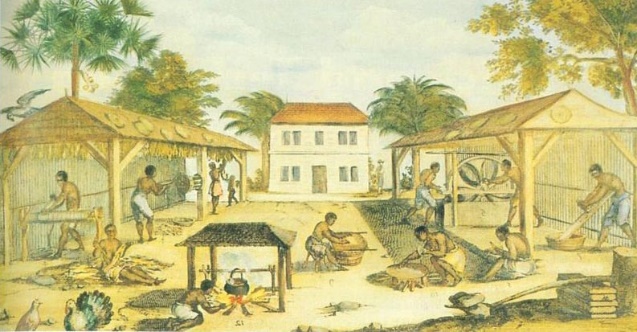

The first enslaved people from Africa were brought to Virginia in 1619 by the Portuguese. Although initially they worked side by side with white indentured servants, by the end of the 17th century, enslaved Africans had become the dominant labor force in Virginia. By 1700, it is estimated that there were over 16,000 enslaved people working on Virginia plantations.

In this 1670 painting, an unknown artist shows enslaved people working on a tobacco plantation. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the transition from Indentured Servitude to Slavery in 17th century Virginia at the PBS website, Africans in America.

|

Maryland was a part of Virginia until 1632 when King Charles I gave a slice of that original colony to his friend, Lord Baltimore. It was basically a Catholic colony and, although named Maryland ostensibly after Queen Henrietta Marie, it was in reality named in honor of the Virgin Mary. Tobacco was the one great cash crop. Servants might be of any class, from poor gentlemen working off the cost of transport, to convicted felons. Many of the English sovereigns transported Scottish and Irish prisoners from the civil wars to Virginia and Maryland, as well as to the West Indies. Africans were also imported, and, in 1664, the Maryland assembly passed a “black code” which declared Africans to be enslaved people for life.

SPANISH SETTLEMENTS IN THE SOUTHEAST

Spain began establishing her second great mission system in the province of Apalachee (the Panhandle area of present-day Florida) around 1630. By the 1670s, 20 smaller missions radiated from the principal one at San Luis (present day Tallahassee, Florida) and a road connected that province with the Spanish city of St. Augustine. Still Spain’s grasp on the area was weak and the garrisons averaged only 300 to 400 men. Because of the fear of the French in Louisiana, Spain established a mission on the Neches River in 1690 and later a garrison at Pensacola, Florida. Even so, Florida remained sparsely populated.

FRENCH SETTLEMENTS IN THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER REGION AND LOUISIANA

The French explorer Jean Nicolet, who had lived among the Hurons since Champlain’s expedition of 1618, explored the Lake Michigan and Wisconsin regions in 1634. In 1675, Jacques Marquette explored the region around Chicago and a few years later, with Father Louis Jolliet, went down the Mississippi to the Arkansas tributary. Rene-Robert La Salle left Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Ontario) in the fall of 1678 and arrived at the Miamis River in November 1681. He and his party reached the Mississippi in February 1682. They reached the Gulf of Mexico on April 7, 1682, and formally took possession in the name of the French king, Louis XIV.

SPANISH SETTLEMENTS IN THE SOUTHWEST

Governor Don Juan de Onate set up the first Spanish government in the southwest at Santa Fe, ten years before the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts. For the next 200 years, Spanish outposts in present day Arizona, Texas, California, and New Mexico slowly developed an economy. The Spanish introduced both the horse and the cow to the southwest. By 1630, there were 1,000 Spaniards in Santa Fe and the immediate area, including 250 garrisoned soldiers. There were fifty priests distributed in ninety villages, each with their own church. By 1680, the population in the area had increased to 2,800 and there were towns at Pecos, Taos, Santa Cruz, and San Marco, but all were evacuated when the Zuni, Hopi, Taino, and Keres peoples, under the leadership of El Pope, revolted. Pope’ made himself governor, but a long drought led to political disarray, allowing the Spaniards to recapture the area of present-day New Mexico and western Texas in 1692.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

A Indigenous perspective on the Pueblo Revolt in 1680: The New Mexico Pueblo people resisted Spanish conversion efforts and forced labor demands. Their sporadic resistance became a concerted rebellion in 1680 under the leadership of the charismatic El Pope. The revolt was the most successful of Native American efforts to turn back European colonists, and for over a decade the Pueblos were free from intrusion. But in 1690 the Pueblos were weakened by drought and Apache and Comanche raiders from the north. Spain retook territory and interrogated and punished the rebels in their “reconquest” of the Pueblo. A Keresan Pueblo man called Pedro Naranjo offered his view of the rebellion and its causes when interviewed by Spanish authorities. What follows is an excerpt of the official report: Asked for what reason they so blindly burned the images, temples, crosses, and other things of divine worship, he stated that the said Indian, Popé, came down in person, and with him El Saca and El Chato from the pueblo of Los Taos, and other captains and leaders and many people who were in his train, and he ordered in all the pueblos through which he passed that they instantly break up and burn the images of the holy Christ, the Virgin Mary and the other saints, the crosses, and everything pertaining to Christianity, and that they burn the temples, break up the bells, and separate from the wives whom God had given them in marriage and take those whom they desired. In order to take away their baptismal names, the water, and the holy oils, they were to plunge into the rivers and wash themselves with amole, which is a root native to the country, washing even their clothing, with the understanding that there would thus be taken from them the character of the holy sacraments. They did this, and also many other things which he does not recall, given to understand that this mandate had come from the Caydi and the other two who emitted fire from their extremities in the said estufa of Taos, and that they thereby returned to the state of their antiquity, as when they came from the lake of Copala; that this was the better life and the one they desired, because the God of the Spaniards was worth nothing and theirs was very strong, the Spaniard’s God being rotten wood. Read the complete account of Pedro’s report (from which these examples were taken). |

|

MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA, AND THE CARIBBEAN

New Spain (modern day Mexico and Central America) was divided into several classes based chiefly on race and color. Indigenous peoples, whose numbers had been greatly reduced as a result of disease, were near the bottom of the social class structure. Above them were the Mestizos, a mixed-race population, born from relations between Spanish men and indigenous women. By the 17th century, private owners of great estates “employed” both native workers and others who belonged to the lower-class structure on their plantations (called haciendas in Spanish). With low wages, high taxes, and massive debts to the landowners, the people who worked on these estates had little control over their live or their livelihood. The highest level of society were the male Spanish settlers, who were politically and economic dominant.

Every European major power was interested in the “sugar islands” of the Caribbean and there were many possessions and trading of island territories between Spain, France, England, and the Netherlands. The Dutch brought sugar cane to the Caribbean from Brazil when they were expelled in 1654, and it soon reached Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dutch Curaçao, Jamaica, and Santo Domingo. After 1685, production increased as planters increasingly relied on an enslaved labor force, supported by the massive importation of enslaved people from Africa. More than 340,000 black enslaved people were brought from Africa in the 17th century to the Caribbean. England established a colony in Jamaica in 1655. By 1690, over 40,000 enslaved people were working on the sugar estates on the island. Continuous revolts and desertions resulted in almost continuous military action throughout the last decades of the 17th century. By the 17th century, the Caribbean Taino Indians were completely exterminated by the diseases brought by Europeans. Settlement in the West Indies was for a long time more extensive than on the American mainland, and, by 1700, there were 121,000 Europeans were living in the area.

NORTHERN AND WESTERN SOUTH AMERICA

As the 17th century began, the Spanish continued their futile search for “El Dorado,” the Land of Gold. The entire west coast of the continent had been explored, however, and the foundations had been laid for every one of the 20 republics of Central and South America, with the exception of Argentina. In one generation, the Spaniards had acquired more territory than ancient Rome conquered in five centuries. By 1650, Potosí (Bolivia) was the largest city in South America, with 160,000 people. Native peoples were forced to work in the great silver mines under extreme hardship conditions. To their numbers were added at least 300,000 Africans who were forcibly brought to Peru in the 17th century.

EASTERN AND CENTRAL SOUTH AMERICA

In Portuguese Brazil, economic and political power was concentrated in the hands of great plantation owners. By 1623, there were 350 sugar plantations. Gold was found in 1690 in the central region of Minas Geraisl. A few years later, diamonds were also found in the same region. In central South America, east of the Andes, and in the more temperate southern zone were wide open lands suitable for sheep and cattle breeders. Since there were few indigenous animals who had been domesticated in what later became Argentina, the empty countryside was filled with European horses and cattle.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the history of cows and horses at the PBS site: “Guns, Germs, and Steel.”

|