30 EUROPE

The 18th century was a transformative period in European history, marked by significant economic, military, and intellectual shifts. Even before the Industrial Revolution’s onset, Europe was undergoing profound change. Spain and Italy were in decline, while England, France, and Sweden were rapidly developing, fueled by the exploitation of mineral resources. Constant warfare characterized this era, with conflicts simmering in various regions simultaneously. Military innovations emerged, including mobile field artillery, accurate mapping, and reorganized army divisions (self-contained units of 12,000 men). Improved road infrastructure facilitated communication and commerce.

Concurrently, European merchants experienced unprecedented prosperity. The Enlightenment’s intellectual ferment stirred, as thinkers reevaluated humanity’s place in the world. Novel philosophical perspectives emphasized reason, progress, and individual rights. This century’s complex interplay of economic, military, and intellectual developments laid the groundwork for the modern European state.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green discuss the key figures and ideas of Enlightenment in Crash Course

|

The 18th century was thus marked by political intrigue and corruption, along with notable paradoxes. Despite significant advancements in physics and chemistry, the practice of medicine lagged far behind. Treatments such as bleeding, cupping, and purging remained common, and an estimated 60 million Europeans died from smallpox during the century. Early in the century, widespread famine occurred due to frost, affecting crops as far south as the Mediterranean coast, with the winter of 1709 being particularly severe, causing many northern rivers and even coastal waters to freeze. Typhus fever took a heavy toll, with a severe epidemic in Sweden and the deaths of approximately 30,000 people in France mid-century. Yellow fever claimed around 10,000 lives in Cadiz, Spain. The majority of the population was illiterate, which hindered access to information and education. Europe burned about 200 million tons of wood annually until around 1790, when coal began to come into more common use.

A significant development in commerce was the concentration of trade profits in warehouses and storage depots. Raw cotton from Central America was stored in Cadiz, Brazilian cotton in Lisbon, Indian cotton pooled in London, and cotton from the Levant in Marseilles. Mainz and Lille became major wine depots. By the end of the century, the fairs of the 17th century were evolving into the warehouse-driven commerce of the 18th century.

GREECE

Throughout the 18th century, Greece remained under Ottoman rule, but Greek seafarers and traders found ways to prosper through secretive trade. They skillfully evaded authorities as blockade runners to make profitable exchanges. A key factor in their success was the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), which allowed Russian ships to enter the Black Sea. Although Russia did not have a strong naval presence there, the treaty enabled Greek sailors to fly the Russian flag, giving them cover for their activities. This arrangement allowed Greek merchants to expand their trade networks, taking advantage of Russia’s growing influence in the region.

As a result, Greek shipowners and traders built wealth and gained valuable experience, setting the stage for Greece’s future economic growth and eventual fight for independence. By seizing these opportunities, Greek seafarers played an important role in connecting Eastern and Western Europe, fostering cultural exchange and trade across the Mediterranean.

UPPER BALKANS

The Balkans in the 18th century were a contested region, caught between the expanding Ottoman Empire and European powers seeking influence. In 1711, Peter the Great’s failed invasion marked a significant moment in the region’s history. The Russian tsar’s vow to free the Balkans from “the enemies of Christ” sparked hopes of liberation, but it ultimately ended in defeat. The Ottoman Empire, which had dominated the region since the 14th century, assembled a massive army of approximately 200,000 soldiers to repel Peter’s forces. This decisive Ottoman victory ensured continued control over the Balkans, with Moldavia and Wallachia remaining vassal states. This setback delayed the region’s emancipation from Ottoman rule, perpetuating a complex web of alliances and power struggles.

A Map of the Balkans (Source: Wikimedia)

Throughout the 18th century, the Balkans remained volatile, with European powers attempting to challenge Ottoman dominance. The Treaty of Passarowitz (1718) and the Treaty of Belgrade (1739) made temporary adjustments to borders, but the Ottoman Empire maintained its grip on the region. The Balkans’ strategic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia ensured its continued significance in international politics, setting the stage for future conflicts and nationalist movements. As the century drew to a close, the seeds of Balkan nationalism began to take root, laying the groundwork for the region’s tumultuous 19th century. The legacy of Ottoman rule, combined with emerging national identities, would shape the Balkans’ complex history for years to come.

ITALY

In 18th-century Italy, a patchwork of independent states and foreign powers competed for control. The once-powerful noble families of Florence and Venice had lost influence, often selling noble titles to the highest bidder. The Habsburgs took over Tuscany in 1737, expanding their power over northern Italy. By the late 1700s, they controlled most of the region, except for Venetia, Genoa, and Savoy. This fragmentation weakened Italy’s ability to resist foreign invasions, turning it into a battleground for European powers.

The Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies managed to maintain some independence, while the Genoese Republic faced threats from neighboring countries. Genoa’s strategic position on the Mediterranean made it a tempting target for expansionist nations. Meanwhile, in France, political changes were underway. The rise of leaders like Napoleon Bonaparte would soon challenge the established order in Europe and have significant repercussions for Italy.

In 1796, Napoleon’s military campaigns began to extend French influence throughout Europe, including Italy. His forces invaded the Italian peninsula, quickly conquering much of the northern region. This marked the start of French dominance over Italy.

Napoleon’s invasion drastically changed Italy’s political landscape. The 1797 Treaty of Campo Formio divided the peninsula into several republics, with Austria gaining control of Venice. Naples, Italy’s largest city, became the capital of the Parthenopean Republic, while the Cisalpine Republic, with Milan as its capital, emerged as another key state. This reshaping of Italy’s map reflected the interests of European powers rather than Italian nationalism, marking a crucial shift in the country’s history.

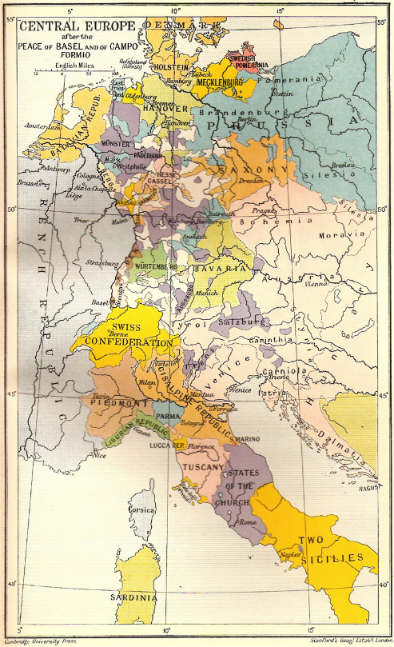

A map showing the division of Central Europe after the Treaty of Camp Formio (Source: Wikimedia)

Southern Italy operated under a feudal system, where powerful barons held significant influence. Food shortages were common, with Florence experiencing famine in more than a quarter of the years between 1591 and 1791. However, the introduction of corn helped ease these shortages, as its high yield made it an appealing crop for Italian farmers. As a result, corn became a staple in the Italian diet, particularly among the peasantry, significantly impacting Italy’s agricultural economy.

Despite these challenges, Italy remained a center for scientific innovation. Italian scholars made significant contributions, such as Luigi Galvani’s work in electrophysiology and Alessandro Volta’s invention of the battery. Giovanni Morgagni’s pioneering research in pathological anatomy earned him recognition as a founder of the field, and his work at Padua’s medical school advanced the understanding of human diseases, inspiring future scientists.

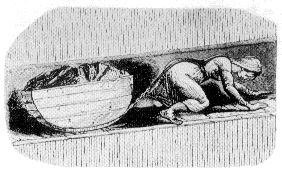

Allessandro Volta used an Electrophorus (shown in this image) to generate electricity. (Source: Wikimedia)

Daily life for ordinary people in 18th-century Italy was marked by hardship and uncertainty. Most Italians lived in rural areas, working as farmers, laborers, or artisans. Their lives were heavily influenced by the seasons, with agricultural cycles dictating the rhythm of daily life. Urban centers, such as Naples and Milan, offered limited opportunities for social mobility, but poverty and disease were rampant. The Catholic Church played a central role in Italian life, with religious festivals, traditions, and rituals providing comfort and community. Women’s roles were largely confined to domestic duties, while education was a privilege reserved for the wealthy. Despite these challenges, Italian culture flourished, with folk traditions, regional cuisine, and family ties providing solace and identity.

Italy’s 18th-century history was marked by foreign domination, internal divisions, and intellectual achievements. This complex mix shaped the nation’s development and set the stage for future growth. The legacy of foreign rule and regional fragmentation continued to influence Italian politics, while Italian scholars and scientists played vital roles in shaping European thought. The 18th century laid the groundwork for Italy’s transformation in the 19th century, a period filled with challenges as the country moved toward unification and nationhood.

GERMAN SPEAKING TERRITORIES

In the 18th century, the region that comprises modern-day Germany was fragmented into numerous small states, bishoprics, and free cities, with the Holy Roman Empire providing a nominal framework for governance, while regional powers like Prussia, Bavaria, and Austria competed for dominance. the Prussian Hohenzollerns and the Austrian Habsburgs, dominated the power structure. The Hohenzollerns were led by notable figures such as Frederick I, Frederick William I, and Frederick II, while the Habsburgs were represented by Emperor Leopold I. This complex web of power also involved Catherine II of Russia and, to a lesser extent, the rulers of England. Approximately 20 million people lived in the region, divided into over 300 independent states, each with its own sovereign prince, but all loosely subject to the Holy Roman Emperor.

The daily life of average German speaking people was marked by hardship and servitude. In 1750, many villages were still “servile,” with serfs owing heavy services and payments to their masters. In fact, serfs weren’t allowed to leave their estates in most German-speaking areas until 1788. Overland transport carried five times more goods than waterways, reflecting Germany’s underdeveloped infrastructure. The population was deeply divided along religious lines, with Catholics predominantly residing in southern and western regions, while Protestants, primarily Lutherans and Calvinists, dominated the north and east. The Thirty Years’ War had left lasting scars, and tensions between Catholics and Protestants persisted. Despite this, religion played a vital role in daily life, with church attendance, festivals, and traditions providing comfort and community. However, religious dissent and intolerance were common, and non-conformists, such as Jews and Anabaptists, faced persecution.

PRUSSIA

The rulers of Prussia stood out for their effective management and quick adoption of improved agricultural techniques. Frederick III, crowned King Frederick I of Prussia in 1701, was a strong supporter of education and the arts. Unfortunately, his reign was marred by tragedy, including a plague that claimed 300,000 lives in 1709. His successor, Frederick Wilhelm I, prioritized developing the Prussian military, which became the fourth-largest army in Europe by the end of his reign. Wilhelm I also focused on improving education, healthcare, and governance in Prussia.

Frederick II, who ascended to the throne in 1740, continued his predecessors’ legacies. He invaded Silesia, starting the War of the Austrian Succession, and eventually secured most of the region through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. This marked the beginning of Prussia’s rise as a major European power and sparked a long-standing rivalry with Austria for leadership in Germany. The competition between these two powers would shape German history for centuries to come.

A portrait of Frederick the Great by Anton Graff, 1781. (Source: Wikimedia)

Frederick II (1712-1786), known as Frederick the Great, stands out as one of the most significant figures in the history of Prussia and its influence in Europe. Renowned as a capable military leader, he transformed the Prussian Army into a model for other European forces. Under his leadership, policies and laws aimed to reflect the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and the common good, positioning Frederick as a forward-thinking monarch in an era of profound change.

The Power of Persuasion: Frederick the Great’s Rise to Prominence

Frederick the Great, the 18th-century King of Prussia, exemplifies the power of persuasion in leadership. Through his exceptional diplomatic skills, strategic communication, and calculated charm, Frederick effectively influenced European politics, expanded Prussia’s territories, and established himself as a major force on the continent. Notably, he persuaded Austria to cede Silesia through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, securing a vital region for Prussia without resorting to further conflict. Frederick’s ability to build alliances, negotiate favorable terms, and manipulate public opinion demonstrates his expertise in persuasion. His memoirs and writings reveal a thoughtful strategist who understood the importance of presenting compelling arguments, adapting to his audience, and leveraging cultural and intellectual connections to achieve his goals.

In the 18th century, Frederick the Great and other rulers like Catherine the Great embraced enlightened absolutism — a political ideal that stated rulers should prioritize the welfare of their subjects over personal or noble interests. Frederick’s reign exemplified the principles of this political philosophy. Leaders like Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia adopted reforms aimed at modernizing their states, improving education, and promoting economic development. The core tenets of enlightened absolutism included the ruler’s responsibility to prioritize the state’s interests, religious tolerance that promoted freedom of worship and coexistence among different faiths, merit-based appointments that chose officials based on ability rather than birthright, and judicial reform that aimd to ensure fairness and equality through updated legal systems. Together, these principles emphasized a commitment to maintain absolute power while governing in way that benefited the state and its citizens. However, these rulers often faced the challenge of reconciling their authority with the aspirations of their subjects, highlighting the complexities of governance during a time when ideas of liberty and equality began to reshape the political landscape of Europe.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

As a leading proponent of “Enlightened Deposition,” Frederick the Great expresses his political aims in the following paragraphs (extracted from his Political Testimony, 1752). Note he emphasizes both the absolute power of the monarch and the necessity of exercising that power in the best interest of the state and its peoples: In a State such as this it is necessary for the sovereign to conduct his business himself, because he will, if he is wise, pursue only the public interest, which is his own, while a Minister’s view is always slanted on matters that affect his own interests, so that instead of promoting deserving persons he will fill the places with his own creatures, and will try to strengthen his own position by the number of persons whom he makes dependent on his fortunes; whereas the sovereign will support the nobility, confine the clergy within due limits, not allow the Princes of the blood to indulge in intrigues and cabals, and will reward merit without those considerations of interest which Ministers secretly entertain in all their doings … The sovereign is the first servant of the State. He is well-paid, so that he can support the dignity of his quality; but it is required of him that he shall work effectively for the good of the State and direct at least the chief affairs with attention. He needs, of course, help: he cannot enter into all details, but he should listen to all complaints and procure prompt justice for those threatened by oppression. |

|

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green explain the theory of Absolute Monarchy and its importance in 18th century Europe in Crash Course in European History #19 |

Beyond their military prowess, Prussian rulers demonstrated a profound commitment to cultural advancement. Frederick William I’s visionary policy made primary education compulsory in 1717, yielding 1,700 new schools and esteemed universities within two decades. This surge in education fueled the growth of science, philosophy, and secularism, gradually diminishing religion’s influence on German society. The arts flourished, with music reigning supreme, as exemplified by the genius of Johann Sebastian Bach, widely regarded as the greatest musical poet in history.

Germany’s cultural renaissance gained momentum toward the century’s end, as literary giants Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich von Schiller published their iconic works. Goethe’s writings sparked a national literary revival, while Schiller’s dramatic masterpieces continue to captivate audiences. Meanwhile, polymath Gottfried Leibniz founded the prestigious Academy of Sciences, further solidifying Prussia’s reputation as a hub of intellectual and artistic excellence.

|

Listen |

|

Listen to the music of Bach played on 18th century instruments.

|

Austria and Hungary

In the 18th century, Austria-Hungary was governed by the influential Habsburg dynasty from their Vienna capital. The Habsburgs faced significant challenges in the early 18th century, including a devastating plague that claimed 300,000 lives in 1711 and the looming threat of the Ottoman Empire’s military might. Prince Eugene of Savoy, a brilliant military strategist, played a crucial role in repelling the Ottoman forces, leveraging the impressive Austrian cavalry and their prized Arabian horses ¹. This victory was a testament to the Habsburgs’ military prowess. Following the premature death of Emperor Joseph I, Charles VI ascended to the throne, bringing with him a deep appreciation for Spanish culture, having been raised to become the King of Spain. This cultural influence is still evident today in institutions like the renowned Spanische Hofreitschule (Spanish Riding Academy).

Charles VI’s passing in 1740 marked the end of the Habsburg male line, but it paved the way for a golden era under his daughter, Empress Maria Theresa. During her reign, spanning 40 years, the Austro-Hungarian Empire expanded to encompass vast territories, including present-day Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Transylvania, Croatia, Slavonia, Dalmatia, Istria, parts of southwestern Germany, Belgium, Lombardy, Tuscany, Sardinia, Piacenza, and Parma

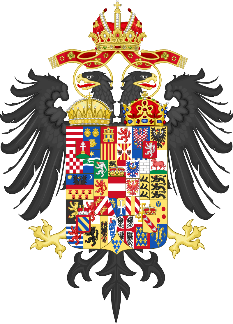

The Coat of Arms of Maria Theresa (Source: Wikimedia)

Austria, home to around six million people, was a prosperous region during the 18th century. Land was primarily owned by nobles and clergy, with serfs working the fields. Empress Maria Theresa played a crucial role in advancing industry by establishing a woolen manufactory in Linz, which employed a significant workforce by 1775. She was also a great patron of the arts and had a close relationship with the musician Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who performed for her at Schönbrunn Castle. The Dutch physician Gerhard van Swieten, a pupil of the botanist Boerhaave, was appointed by the empress as her personal physician. He opened a medical school in Vienna that attracted students from across Europe. In 1784, the Allgemeines Krankenhaus (General Hospital) was established to provide teaching and care for the underprivileged.

The Complexities of Perspective: Maria Theresa’s Reign

Maria Theresa’s reign showcases a complex and multifaceted example of perspective-taking, with both exemplary and troubling instances. She demonstrated cultural sensitivity and empathy in her relations with Hungary, recognizing grievances and acknowledging their unique heritage, but her treatment of Jews reveals a striking lack of perspective-taking. The 1744 decree expelling Jews from Prague and other Bohemian cities, fueled by anti-Semitic sentiment and economic resentment, resulted in widespread suffering. However, Maria Theresa’s later reforms, such as the 1754 Toleration Patent granting limited rights to Jews, suggest a partial recognition of her earlier mistakes. Her legacy highlights the challenges of perspective-taking, including the influence of societal attitudes and advisors. Despite inconsistencies, Maria Theresa’s record demonstrates the importance of growth, self-reflection, and empathy in leadership. Ultimately, her complex example serves as a valuable lesson in the nuances and imperatives of effective perspective-taking.

After 1765, Maria Theresa shared her power with her son Joseph II (1741-1790) until her death in 1780. Joseph was ahead of his time, implementing reforms that would not be seen again for 150 years, such as the abolition of serfdom and the banning of torture. He also decriminalized religious heresy as a political offense. Joseph II’s progressive policies laid important groundwork for future developments in social welfare in Austria.

BOHEMIA (the Czech Republic)

In the 18th century, Bohemia was controlled by the Habsburgs. Peasants in Bohemia and Moravia endured harsh conditions, facing limited social mobility and economic opportunities. Their struggles were worsened by the persecution of Jews, which intensified in 1744 when Empress Maria Theresa imposed stricter regulations on Jewish communities. These included increased taxes, restrictions on where Jews could live, and limitations on their economic activities. As a result, many Jews sought refuge in more tolerant regions, including some who fled to England. This period of repression had a profound impact on the social fabric of Bohemia, fostering widespread discontent and laying the groundwork for future unrest.

As the century drew to a close, a sense of national unity began to emerge among the Bohemians. Nationalist ideas, inspired by the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, started to influence the upper classes, fostering a growing awareness of a shared Bohemian identity. This rising sentiment created tensions with the Habsburg rulers. In response, Leopold II (1747-1792) tried to appease the Bohemians through targeted reforms. He was notably the last Austrian ruler to be crowned King of Bohemia, marking a symbolic end to traditional monarchical ties between the Habsburgs and Bohemia. As the century transitioned into a new era, the Bohemians’ developing national consciousness would continue to shape their relationship with the Habsburg Empire.

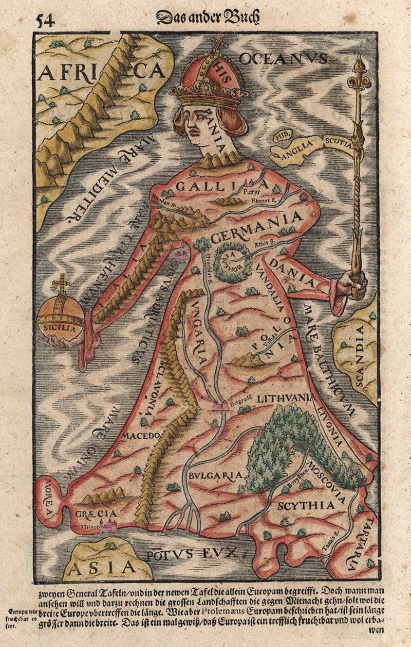

This 16th century map shows Bohemia as the heart of Europe (Source: Wikimedia)

SWITZERLAND

In the 18th century, the Swiss Federation consisted of thirteen cantons, a diverse entity comprising three distinct peoples, four languages, and two dominant faiths. This complex tapestry was characterized by significant political and social disparities. Most cantons operated as oligarchies, where power was concentrated in the hands of a few elite families, leaving limited political freedom for the lesser nobility and peasants. The canton of Bern, encompassing approximately one-third of Switzerland, held significant sway. However, the rival Christian faiths – Protestantism and Catholicism – frequently clashed, with some cantons prohibiting non-Catholic worship and others forbidding non-Protestant practices. This sectarian divide was exemplified by Geneva, a separate republic that adhered to Calvinist Protestantism and French language, which benefited economically from the influx of French Huguenot refugees.

The Swiss Federation’s fragile balance of power was disrupted in 1789 when Napoleon’s armies overran the region. Napoleon subsequently established the Helvetic Republic, a centralized entity closely aligned with France. This radical transformation aimed to unify Switzerland under a single, democratic government, abolishing the traditional cantonal system. Although the Helvetic Republic’s brief existence (1798-1803) was marked by instability and power struggles, it laid the groundwork for Switzerland’s future federal structure. Napoleon’s influence ultimately yielded a more unified Swiss state, paving the way for the country’s emergence as a modern nation. The legacy of this period continues to shape Switzerland’s identity as a multicultural, multilingual, and multi-faith society. Today, Switzerland’s linguistic diversity endures, with approximately 63% speaking German, 23% French, 8% Italian, and 4% Romansh. The French-speaking cantons, including Geneva, Vaud, and Neuchâtel, maintain strong cultural ties to France, while the German-speaking cantons, such as Zurich and Bern, retain strong connections to Germany and Austria. Italy’s influence is evident in the southern canton of Ticino, and Romansh persists in the southeastern canton of Grisons

WESTERN EUROPE

The 18th century was marked by incessant warfare in Western Europe, with Spain, France, and England being the primary belligerents. However, this period also witnessed significant transformations in living conditions across the continent. The emergence of luxury and industrialization led to a critical shift: the separation of living quarters from workshops and businesses. Previously, merchants’ and artisans’ homes were integrated with their shops, with the master’s dwelling above and apprentices’ quarters on the top floor.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about War in European in the 18th century in Crash Course in European History #20

|

Industrial activity permeated every town and city, with looms, forges, brickworks, tile factories, and sawmills operating on a widespread scale. Certain regions boasted massive concentrations of workers, such as Newcastle’s 30,000 coal miners, Languedoc’s 450,000 weavers, and 1.5 million textile workers in northern France’s five provinces. Conversely, commerce and wealth remained concentrated in the hands of a select few affluent families. The stark disparity between the rich and poor was exemplified in Lombardy, where the nobility comprised merely 1% of the population yet owned over 50% of all property.

SPAIN

During the 18th century, Spain engaged in several conflicts with European nations, including the War of the Polish Succession, the War of Jenkins’ Ear against England, the War of the Austrian Succession, and the Seven Years’ War. These wars, spanning from the 1730s to the late 1700s, profoundly affected the country’s development. Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain and grandson of Louis XIV, began his reign in 1700 and ruled until 1746. His successor, Ferdinand VI, ruled until 1759, when his half-brother, Charles III, took the throne.

Charles III’s reign, from 1759 to 1788, brought major reforms that transformed Spain. He advanced science, university research, and trade, while modernizing agriculture and reducing the Church’s influence. Charles III’s reforms made a lasting impact. He modernized agriculture, established the Royal Academy of History, and strengthened Spain’s army and navy. His visionary policies earned him recognition as one of Spain’s greatest Bourbon kings.

A portrait of Charles III by Anton Mengs, 1761 (Source: Wikimedia)

One of his key decisions was to promote the expansion of the textile industry. By 1787, Valencia had 5,000 looms producing Europe’s finest silk, and Catalonia’s cotton industry employed 80,000 workers, mostly women, in 100 factories by 1790. This industrial growth boosted urban development but left the poor struggling while wealth concentrated in the hands of the nobility and merchants.

Workers in the cotton industry endured arduous conditions. Laborers, predominantly women and children, worked exhaustive 12-hour shifts, six days a week, in cramped and poorly ventilated factories. Their meager wages barely covered essential expenses, forcing many to reside in company-owned housing, further solidifying their dependence on factory owners. Physically demanding tasks, such as operating spinning jennies and looms, took a toll on workers’ health. Cotton dust filled the air, causing respiratory issues, while machinery accidents were common. Women, who comprised most of the workforce, faced additional challenges, including harassment and limited social mobility.

Workers in the cotton industry endured arduous conditions. Laborers, predominantly women and children, worked exhaustive 12-hour shifts, six days a week, in cramped and poorly ventilated factories. Their meager wages barely covered essential expenses, forcing many to reside in company-owned housing, further solidifying their dependence on factory owners. Physically demanding tasks, such as operating spinning jennies and looms, took a toll on workers’ health. Cotton dust filled the air, causing respiratory issues, while machinery accidents were common. Women, who comprised most of the workforce, faced additional challenges, including harassment and limited social mobility. This bleak reality was not unique to Spain; across Europe, the emergence of factories and industries in the 18th century brought similar exploitative conditions, from the textile mills of England to the ironworks of Sweden. As industrialization transformed the continent, a striking pattern emerged: wealth concentrated in the hands of a few elite entrepreneurs and nobles, while the toiling masses remained mired in poverty, their labor fueling the growth of an economy that largely excluded them from its benefits.

PORTUGAL

By the 18th century, Portugal’s once-powerful presence in the Indian Ocean had significantly declined. Its empire had been reduced to a single colony, Goa, India, where it occasionally sent shipments of convicts. Weakened by internal corruption and external threats, Portugal forged an alliance with England, formalized by the Methuen Treaty of 1703. This treaty gave Portugal a favorable position in the wine trade and allowed English manufactured goods to enter Portugal tax-free. As a result, England dominated Portugal’s economy, leading some Europeans to refer to Portugal as an “English colony.” This relationship further eroded Portugal’s sovereignty and increased its dependence on its stronger ally.

In Lisbon, the consequences of Portugal’s decline were evident. As the city grew, wealth concentrated in the hands of a small elite, while the majority lived in poverty. Shantytowns emerged on the outskirts, replacing once-productive farmland. An estimated 10,000 homeless men, women, and children roamed the streets, reflecting the deep socioeconomic inequality of the period. While a few amassed great wealth, most struggled in harsh conditions, contributing to instability and impeding Portugal’s recovery as a major European power.

FRANCE

Like the previous century, the 18th century in Europe was heavily influenced by French culture and military power. One of the most difficult years for France was 1709, when an extreme winter caused rivers and even the Atlantic coastal waters to freeze. Crops such as winter wheat, vines, and fruit trees were destroyed, leading to widespread starvation. Public and private finances were in crisis, and children starved to death. By 1717, Paris had grown to a population of around 500,000, making it the third-largest city in Europe. However, the streets were narrow and crowded, filled with the deafening noise of daily life. The stench from human waste dumped from windows, manure piles, and slaughtered animal remains made the city unbearable for many. After midnight, when the streetlamps were extinguished, the streets became dangerous. This situation was common in most European towns of the 18th century, whether large or small. Bathrooms in homes were rare, and fleas, lice, and bedbugs plagued Paris, London, and other cities. An average of 20,000 people died in Paris every year, even after the 1780s. Hardly anyone took baths, and those who did bathed only once or twice a year.

In the countryside, peasants were extremely poor, and a series of failed harvests between 1773 and 1789 worsened their situation. There were at least sixteen major famines throughout the 18th century, along with many local food shortages. The last major plague outbreak in Western Europe occurred in Marseilles in 1720. Although glass windows were common in Paris, oiled paper was still used for windows in Lyons and other provinces. Despite these hardships, France set the fashion trends for all of Europe. French mannequin dolls, dressed in the latest styles, were sent across the continent for dressmakers to copy.

This painting of the Duchesse de Polignac illustrates the fashion of Paris in the 18th century. (Source: Wikimedia)

Louis XIV, the renowned Sun King of France, ruled with absolute power from 1643 until his death in 1715, marking the longest reign of any European monarch. During his final years, he intensified the persecution of Protestants, solidifying his legacy as a staunch defender of Catholicism. Upon his passing, his great-grandson, Louis XV, ascended to the throne at just five years old, with Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, serving as regent. However, Louis XV’s reign was marked by turmoil, including a violent workers’ strike in Abbeville in 1716 that required armed intervention. As Louis XV indulged in lavish pleasures, he remained detached from the growing discontent among his people, who struggled to make ends meet. This disconnect would ultimately sow the seeds of discontent that would boil over in the French Revolution. Louis XIV’s legacy continued to shape France under Louis XV, but the younger king’s apathy and self-interest would prove to be a far cry from the strong leadership and vision that had defined his predecessor’s rule.

One of Louis XV’s mistresses, Madame de Pompadour, emerged as one of the most notable women of the 18th century. Louis respected her intelligence, allowing her to act as an unofficial prime minister and advisor. Her influence extended beyond politics; she promoted scientific, economic, and philosophical advancements. Pompadour urged Louis to expel the Jesuits from France and supported his alliance with Austria, which ultimately led France into the Seven Years’ War. After suffering defeat in this conflict, France lost Canada and its territories in India to England.

A painting of Madame de Pompadour by Francis Boucher, 1758 (Source: Wikimedia)

Important Enlightenment philosophers emerged in 18th century France. Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that humans are naturally good but become corrupted by the class divisions in hierarchical societies. Voltaire, born François-Marie Arouet, gained fame as a playwright, poet, historian, and philosopher, becoming a confidant to kings and Catherine the Great of Russia. Notable painters of the time included François Boucher, Jean-Baptiste Chardin, and Quentin de La Tour. Charles Louis de Montesquieu made significant contributions to discussions of religion and government, while Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert published the influential Encyclopédie in 1750.

The Paradox of Enlightenment: Intercultural Competence and Its Limitations

The 18th-century French philosophers, known as the Enlightenment thinkers, embody a complex mix of intercultural competence and limitations. On the positive side, thinkers like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot demonstrated remarkable openness to diverse perspectives, engaging with ideas from ancient Greece, Rome, and China, as well as Islamic and Native American cultures. Their emphasis on reason, tolerance, and universal human rights helped lay the groundwork for modern democracy and human rights movements. However, their writings also reveal a paternalistic and Eurocentric worldview, often perpetuating stereotypes and biases against non-European cultures. Voltaire, for instance, made troubling statements about Africans, describing them as “beings” with “small brains” and questioning their full humanity. Similarly, Rousseau’s depiction of the “noble savage” reinforced simplistic and romanticized notions of indigenous peoples. This paradox highlights the complexities of intercultural competence, where even well-intentioned individuals struggle to transcend their cultural biases, underscoring the need for ongoing self-reflection and critical examination of one’s own cultural assumptions..

Jean Maritz (1711-1794), a pioneering Swiss-born French engineer, revolutionized France’s military capabilities. By casting cannons as a solid piece of metal and then boring out the barrel, Maritz created cannons with straight and uniform bores, significantly enhancing safety, accuracy, lightness, and reliability. These innovations allowed for a closer fit between cannonball and gun tube, reducing “windage” allowance and enabling the use of smaller powder charges to achieve greater velocity.

However, France’s financial struggles during Louis XVI’s reign (1754-1793) posed a significant threat to the country’s stability. With the king’s treasury depleted, he was forced to convene the Estates General, an ancient representative body, in 1789 to garner support for new taxes. The Estates General comprised nobles, clergy, and the middle class, known as the ” third estate,” each holding effectively one vote. Recognizing the nobles and clergy would dominate the assembly, the third estate broke away, formed the National Assembly, and vowed to establish a constitution and reform administration.

This pivotal moment in French history led to the creation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a document encapsulating Enlightenment ideals of human equality and freedom. It also endorsed representative government, setting in motion the events of the French Revolution. The National Assembly’s bold actions reflected the growing discontent among the French people, who were increasingly frustrated with the monarchy’s inability to address the country’s economic woes.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

The Declaration of the Rights of Man, approved by the National Assembly of France on August 26, 1879, expresses the fundamental Enlightenment concept of natural rights and its political implications in the following statements: 1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. 2. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. 3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation. 4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law. 5. Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law, and no one may be forced to do anything not provided for by law. 6. Law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has a right to participate personally, or through his representative, in its foundation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. |

|

The French Revolution transformed France into a limited monarchy between 1789 and 1791. King Louis XVI was effectively imprisoned in the Tuileries, and the reorganized National Assembly governed the country, implementing significant reforms. While they aimed to maintain relative peace, the period was also marked by rising tensions, especially after events like the Flight to Varennes in 1791, which heightened distrust in the king. The Assembly revamped the penal code, ended heresy persecutions, and opened military ranks to all citizens. This stability was crucial for establishing a new political framework, as the Assembly sought to create a more equitable society, addressing social inequality and economic hardship. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for the Revolution’s next phase.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the French Revolution in a series of videos produced by the Khan Academy: |

Both the French and American Revolutions were influenced by Enlightenment ideals, including liberty, equality, free trade, religious tolerance, republicanism, and human rationality. Leaders in both countries believed that human action could improve societal arrangements. Thinkers like Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu had a profound impact on the revolutionary movements. However, key differences distinguished the two revolutions: the American Revolution was a colonial revolt against imperial power, while the French Revolution was an internal conflict aimed at restructuring society.

In America, colonists sought freedom from British rule, whereas French revolutionaries aimed to create a new social order by dismantling the monarchy and its institutions. The French perceived their revolution as a fresh start, declaring 1792 “Year 1” of a new era. This radical vision led to volatility and violence, with various factions vying for power. The storming of the Bastille symbolized the Revolution’s rejection of absolute monarchy. Peasants attacked lordly castles, burning documents that recorded their feudal obligations. The execution of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in 1793 marked the end of the monarchy and the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

Under Maximilien Robespierre’s leadership, the Committee of Public Safety executed thousands deemed enemies of the state. Robespierre and his supporters aimed to equalize property and abolish class distinctions. The Reign of Terror, lasting from 1793 to 1794, was marked by brutal violence and repression. The Committee’s actions sparked widespread fear and opposition, ultimately leading to Robespierre’s downfall. In July 1794, Robespierre was arrested and executed, ending the Reign of Terror. The subsequent Thermidorian Reaction (named after the month in which the coup took place) aimed to stabilize France and establish a more moderate government.

Women played a pivotal role in the French Revolution, actively participating in protests, demonstrations, and political debates. Despite their contributions, women’s rights were largely overlooked in the Revolution’s early stages. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) failed to address women’s equality, sparking discontent among female revolutionaries. Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793), a prominent feminist writer and activist, responded with her influential Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1791). This document challenged the patriarchal norms of the time, advocating for women’s education, property rights, and equal participation in government. De Gouges’ bold stance came at a great personal cost; she was eventually arrested and executed by guillotine on November 3, 1793. Other notable female revolutionaries, such as Charlotte Corday and Pauline Léon, also fought for women’s rights and social justice. The Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, founded in 1793, pushed for women’s involvement in politics and social reform. Although the Revolution’s male leaders largely ignored women’s demands for equality, the movement laid groundwork for future feminist movements in France.

Perspective Taking and Social Justice: The Enduring Impact of Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges’ life and writings exemplify the power of perspective taking. Born into poverty and illiteracy, de Gouges (1748-1793) defied societal norms by educating herself and becoming a prominent writer and activist. Her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (1791) demonstrates her ability to take the perspective of marginalized women, challenging the patriarchal norms that silenced and oppressed them. De Gouges’ advocacy for women’s rights, abolition of slavery, and social justice reveals her capacity to consider multiple viewpoints and empathize with diverse experiences. By putting herself in others’ shoes, de Gouges humanized the struggles of women and slaves, amplifying their voices and sparking critical conversations. Her execution by guillotine in 1793 underscores the risks she took by challenging dominant perspectives. De Gouges’ legacy serves as a testament to the transformative potential of perspective taking, encouraging us to question our assumptions, listen to diverse voices, and strive for empathy and understanding.

Following the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, France entered a period of relative stability. The Committee of Public Safety’s powers were curtailed, and many of its members were arrested or executed. In 1795, a new constitution established the Directory, a five-member executive council that governed France. The French Revolution’s impact reverberated across Europe, fueled by the French people’s euphoria over abolishing their nobility. Emboldened, they formed armies to spread revolutionary ideals throughout the continent, establishing republican governments in Brussels, Holland, Savoy, Switzerland, and southern Germany. This bold expansionism led to a declaration of war against England, drawing the European powers into a broader conflict. The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte marked a turning point in France’s military fortunes. Under his leadership, the Republican Army achieved stunning victories against the forces of Savoy and Austria in 1796, conquering much of northern Italy. As Napoleon’s power grew, so did his vision for a reorganized Europe, paving the way for his eventual ascent to emperor and the reshaping of the continent.

In 1798, Napoleon led his army into Egypt, aiming to disrupt British trade routes and expand French influence. Although the expedition ultimately failed, Napoleon’s military prowess and strategic thinking remained unmatched. Returning to France in 1799, Napoleon found the Directory, France’s ruling council, mired in corruption and inefficiency. Seizing the moment, Napoleon joined forces with Paul Barras and other influential politicians to orchestrate the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799), overthrowing the Directory and establishing the Consulate, with Napoleon as its leader, marking the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic Empire.

A painting of a 23-year old Napoleon by Felix Philippoteaux (Source: Wikimedia)

The French Revolution’s transformative power extended far beyond politics, sparking a cultural and intellectual renaissance that reshaped French society and resonated throughout Europe. One significant outcome was the elevated status of women, who, although denied full political rights, gained momentum in their pursuit of educational opportunities and political empowerment. This sparked a broader international movement for women’s rights, as females increasingly demanded recognition and equality. On a practical level, the Revolution eradicated remnants of the monarchy, renaming streets, destroying royal monuments, and abolishing noble titles. The Roman Catholic Church, having aligned itself with the monarchy, suffered a significant loss of political influence and popular support.

This spirit of innovation and progress also characterized the scientific advancements of the late 18th century. René Laennec (1781-1826), Pierre Simon Laplace (1749-1827), Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794), Theophile de Bordeu (1722-1776), and Pierre Fauchard (1678-1761) were pioneers who embodied the Revolution’s emphasis on reason, curiosity, and human potential. Their groundbreaking discoveries – from the stethoscope to modern chemistry and dentistry – reflected the same desire for progress and improvement that drove the Revolution’s social and political reforms. As France shed its feudal past, these scientists helped forge a new future, harnessing human ingenuity to improve lives and expand knowledge.

THE NETHERLANDS

The 18th century witnessed the Netherlands’ prominence as a maritime and financial hub. The country’s shipyards supplied vessels to all of Europe, while its capital, Amsterdam, boasted a staggering population of over 600,000 by 1717, making it Europe’s second-largest city. The iconic Amsterdam Exchange Building, completed in the 17th century, was the epicenter of commercial activity. Thousands converged daily at noon, transforming the exchange into a bustling hub. As the center of European finance, Amsterdam, alongside London, Paris, and Geneva, formed a formidable banking axis.

However, the Netherlands’ small population and limited natural resources ultimately hindered its sustainability as a great power. By 1784, a three-way struggle for dominance emerged among the middle class, patrician families controlling the Estates General, and the influential governor, known as the Stadtholder. Prussian intervention in 1787 further consolidated the Stadtholder’s power. Yet, in 1795, French revolutionaries seized control of Amsterdam, capturing the Dutch fleet as it lay frozen in harbor ice. This marked the end of Dutch dominance, as the French Revolution’s ripple effects reshaped European politics.

Medicine emerged as a shining intellectual achievement in 18th-century Holland. The renowned medical school at the city of Leiden boasted illustrious faculty, including botanist Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) and anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770). Their students went on to lead the medical profession across Europe. Boerhaave’s emphasis on clinical practice and Albinus’s meticulous anatomical illustrations raised the standards of medical education. Leiden’s influence extended beyond national borders, cementing the Netherlands’ reputation as a hub of medical innovation.

A portrait of Herman Boerhaave by J. Chapman, 1798. (Source: Wikimedia)

BELGIUM

The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) brought an end to the War of the Spanish Succession, conclusively resolving the prolonged conflict between Spain and France over control of Belgium. As a result, Belgium was absorbed into the Holy Roman Empire, falling under the dominion of the Hapsburgs. For nearly eight decades, Belgian territories remained subject to Hapsburg rule. However, in 1787, a nascent independence movement emerged in southern Belgium, driven by a desire for self-governance. Inspired by the American Revolution, the movement’s leaders boldly declared the establishment of “The Republic of the United Belgian States.” This audacious bid for independence, though well-intentioned, ultimately fizzled.

The Belgian independence movement’s failure paved the way for France’s annexation of the region in 1795. Under French rule, Belgium underwent significant administrative and cultural transformations. The French Revolution’s emphasis on liberty, equality, and fraternity resonated with many Belgians, who saw the annexation as an opportunity for modernization. However, others resisted French domination, leading to simmering tensions. The French occupation lasted until 1815, when the Congress of Vienna redrew Europe’s map, and Belgium became part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. This marked the beginning of a new era for Belgium, one that would eventually culminate in full independence in the 19th century.

ENGLAND AND WALES

By the end of the 18th century, the population of England and Wales had grown to over nine million people. This increase followed a trend that saw the population rise from around 2 million in the 11th century to 4 million by the 1600s and 5.5 million by the end of the 17th century. The 18th century brought significant political and cultural changes. After King William died in 1702, Queen Anne ruled until 1714, during which time the Augustan Age of English literature thrived with notable figures like Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. England’s victory in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) allowed it to gain control of Gibraltar, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland. Parliament firmly established itself as the supreme power in the country. When Anne died, George I of Hanover (1714–1727) took the throne. His refusal to learn English and frequent absences from the country caused discontent. Despite these issues, Sir Robert Walpole became the first prime minister and strengthened the British economy. Political power continued to shift toward Parliament, especially the House of Commons, while England expanded its influence in North America and India.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Read about the development of the Novel in 18th century England in an

|

Prior to 1715, rural life in England remained largely unchanged for centuries. However, the advent of the factory system revolutionized agriculture, farming, and transportation, transforming England into the world’s premier industrial hub. A pivotal innovation was James Watt’s steam engine, patented in 1769, which significantly enhanced industrial productivity. As England’s forests dwindled – only four of the original sixty-nine great forests remained by century’s end – the need for alternative fuels grew. Abraham Darby’s discovery of coke, a sulfur-infused coal derivative, efficiently fueled the smelting process, catapulting England to global leadership in iron manufacturing by 1760.

The convergence of these technological advancements and transportation breakthroughs, including steamships and railways, propelled the Industrial Revolution forward. Coal became the primary fuel source, supplanting wood. The increased availability of iron enabled the construction of machinery, factories, and infrastructure. This transformative period saw England’s transition from manual labor to mechanization, laying the groundwork for unprecedented economic growth. As the Industrial Revolution gained momentum, England solidified its position as a global industrial powerhouse.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green discuss the Industrial Revolution in Crash Course in European History #24.

|

The Industrial Revolution in England had a huge impact, drastically increasing the nation’s industrial output—fifty times more in some areas—between 1750 and 1900. As this revolution spread to Europe and the United States, it improved the quality of life for many people. However, it came with serious environmental damage. Large-scale extraction of nonrenewable fuels ruined landscapes, while factories polluted rivers with waste. Coal-burning industries filled cities with thick smog, causing widespread health problems like respiratory illnesses.

The Revolution also caused major unrest among workers. Inventions like John Kay’s flying shuttle (1733) and James Hargreaves’ spinning jenny (1764) boosted production but led to job losses, sparking violent backlash. Kay’s house was attacked, forcing him to flee to France, where he died in poverty. Hargreaves faced similar opposition. These inventors’ stories show how technological progress often clashed with social stability.

A contemporary model of Hargreaves’ spinning jenny (Source: Wikimedia)

The impact of the Industrial Revolution in England was immense. Industrial output increased fifty-fold between 1750 and 1900. As the Revolution spread throughout Europe and to the United States, it improved the material life of humankind in many ways. But it also greatly damaged the environment. The massive extraction of nonrenewable fuels (coal, iron ore, petroleum, gas, and much more) to fuel the engines that formed the material basis for production altered the landscape in many ways. Raw sewage and industrial waste ran freely into rivers and streams, turning them into poisonous cesspools. Smoke from coal-burning industrial centers created smog that was sometimes so thick that it limited vision. This smoke also impacted the ability of people to breathe, sharply increasing the cases of respiratory illnesses.

The Industrial Revolution deeply impacted human lives, creating two disparate societies: the affluent country gentlemen and the urban poor. London, Europe’s largest city, exemplified this divide. Overcrowding, filth, and disease plagued its slums, where 64% of children died before age ten. The laboring classes faced monumental changes as industrialization drew them to cities. They endured unsanitary tenements, long hours, low wages, child labor, and hazardous working conditions.

As urbanization intensified, living conditions deteriorated. Fires threatened densely populated areas, and education remained inaccessible to most. In 1800, London lacked even a single public bathing establishment. The working poor struggled to survive amidst monotony and danger. Their plight underscored the Revolution’s human cost, highlighting the need for social reform.

An image of a young girl working in a coal mine from the 18th century (Source: Wikimedia)

At the same time, advancements in farming machinery and techniques, such as Jethro Tull’s seed drill (1701), crop rotation, and fallowing, significantly enhanced agricultural productivity. These improvements led to more diverse and nutritious diets, contributing to a notable population increase. The 18th century also saw a remarkable rise in consumerism, particularly in England. For example, tea consumption surged from eight million pounds in the 1770s to around two pounds per person per year by the century’s end.

The era also introduced exotic culinary delights, highlighting the impact of globalization on English cuisine. One notable example is the arrival of ketchup (or catsup), which originated in China and traveled to England via India and Southeast Asia. Its incorporation into English cuisine exemplifies the cultural exchange and cross-pollination that characterized the period.

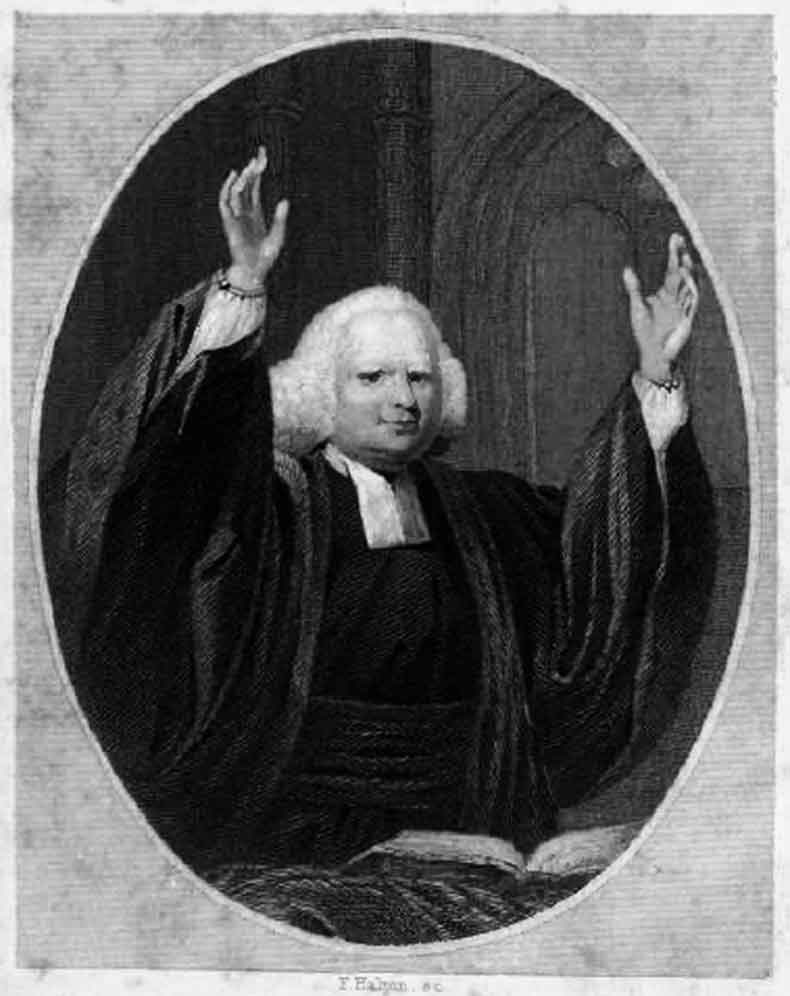

During the 18th century, a revitalized expression of Christianity in England. Methodism was founded by John and Charles Wesley, along with George Whitefield and a small group of Oxford students and teachers. Initially, this small group of devout Anglicans sought to practice Christianity with systematic rigor, earning them the label “Methodists.” John Wesley’s encounter with Moravian Brothers in Georgia significantly influenced his approach, adopting their fervor and principles. This exposure led to a transformative experience for Wesley, solidifying his commitment to evangelism and social reform. Methodism’s emphasis on personal piety, moral discipline, and community engagement resonated deeply with the working class and marginalized populations. As a result, the movement gained momentum, spreading throughout England and beyond.

Through impassioned preaching, John Wesley and George Whitefield, along with Charles Wesley’s poignant hymns, effectively captivated lower-class England and spread Methodism’s message. Their theology, which emphasized sin, repentance, and moral redemption, shared similarities with Puritan teachings but also introduced new ideas, such as the doctrine of Christian perfection. Methodism’s influence extended beyond spiritual renewal, addressing social ills such as poverty, illiteracy, and inequality. By the time of John Wesley’s death in 1791, Methodism had gained significant traction, with approximately 79,000 adherents in England and 40,000 in the United States.

George Whitefield is shown preaching in this 19th century engraving. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Near the end of his life in 1786, at the age of 83, John Wesley published a short pamphlet entitled, On Methodism. Speaking of himself in the 3rd person, he described the beginnings of Methodism in this way: In the year 1729 four young students in Oxford agreed to spend their evenings together. They were all zealous members of the Church of England, and had no peculiar opinions, but were distinguished only by their constant attendance on the church and sacrament. In 1735 they were increased to fifteen; when the chief of them embarked for America, intending to preach to the heathen Indians. Methodism then seemed to die away; but it revived again in the year 1738; especially after Mr. Wesley (not being allowed to preach in the churches) began to preach in the fields. One and another then coming to inquire what they must do to be saved, he desired them to meet him all together; which they did, and increased continually in number. In November, a large building, the Foundery, being offered him, he began preaching therein, morning and evening; at five in the morning, and seven in the evening, that the people’s labor might not be hindered. … From this short sketch of Methodism, (so called,) any man of understanding may easily discern, that it is only plain, scriptural religion, guarded by a few prudential regulations. The essence of it is holiness of heart and life; the circumstantials all point to this. And as long as they are joined together in the people called Methodists, no weapon formed against them shall prosper. Read the full pamphlet here. |

|

In addition to religious changes, writers and musicians in England made remarkable advancements in literature and music. Henry Fielding’s comic novel, Tom Jones (1749), delighted readers with its witty satire and engaging narrative. Other notable authors of the era included Thomas Gray, whose poignant “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751) remains a timeless classic. Samuel Johnson’s incisive writings and David Hume’s philosophical and historical works also left an indelible mark on English literature. Hume, a Scottish émigré, brought a unique perspective to his writings, influencing the development of Enlightenment thought.

In the realm of music, George Friedrich Handel, a German-born composer, dominated the London scene. His prolific output included operas, oratorios, anthems, and organ concertos, but it is his iconic oratorio, Messiah (1742), that continues to captivate audiences worldwide. This majestic choral work, featuring the celebrated “Hallelujah Chorus,” showcases Handel’s mastery of Baroque music and cemented his legacy as one of the greatest composers of all time.

|

Listen and Enjoy |

|

Listen to the Royal Choral Society sing the Alleluia chorus of Handel’s Messiah.

|

A drawing of James Lind superimposed over the title page of his book discussing scurvy (Source: Wikimedia)

Despite significant medical advancements, 18th-century England continued to grapple with infectious diseases. Typhus fever persisted in sporadic, mild epidemics, while scarlet fever surged in incidence, claiming one life out of every 30 infected individuals by 1750. Smallpox remained a pervasive and deadly scourge, with mortality rates ranging from 15% to 30%. London witnessed alarming smallpox-related deaths, exceeding 1,000 fatalities in all but nine years throughout the century, with a staggering 3,000 deaths reported in 1759. The physical scars of smallpox were a stark reality, with one-third of England’s inhabitants bearing pockmarks. Amidst this landscape, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu introduced the concept of inoculation using pus from smallpox lesions, adopted from Ottoman practices. Although inoculation offered some protection, it was not without risks. A breakthrough came in 1798 when Edward Jenner published his groundbreaking paper on cowpox vaccination. Jenner’s innovative approach harnessing cowpox to confer immunity against smallpox revolutionized disease prevention and paved the way for modern vaccination.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Mary Montagu (depicted in the picture below in Ottoman garb) wrote of her observations of the Ottoman use of vaccines in a letter to Mrs. S. C. in 1717:

There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated. People send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small-pox: they make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together) the old woman comes with a nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what veins you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lye upon the head of her needle, and after that binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell; and in this manner opens four or five veins… The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day, and are in perfect health to the eighth (day). Then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three. They have very rarely above twenty or thirty in their faces, which never mark; and in eight days’ time they are as well as before their illness. Read the full letter here. |

|

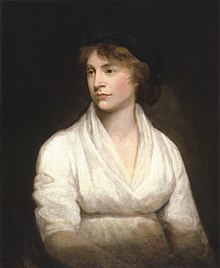

Mary Wollstonecraft emerged as a pioneering advocate for women’s rights during this era. She applied Enlightenment ideas to champion women’s education, challenging patriarchal assumptions that had gone untested. Although Enlightenment philosophers challenged traditional political societies, they largely accepted patriarchal norms. Wollstonecraft’s radical pamphlet, “A Vindication of the Rights of Man” (1790), asserted women’s rights as human beings, emphasizing education and intellectual well-being. Wollstonecraft argued that women possess the same rational faculties as men and deserve equal rights. She advocated for education, believing society should prioritize women’s intellectual well-being. However, it is essential to note that Wollstonecraft’s views fell short of modern feminist standards. She did not advocate for women’s suffrage or equal political rights, focusing instead on education and intellectual equality. Her arguments were groundbreaking for her time but did not fully encompass the scope of feminist ideals that would emerge in the 19th century. Wollstonecraft’s work paved the way for future feminist movements, despite its limitations. Her emphasis on women’s rational capabilities and natural rights influenced subsequent generations of feminist thinkers.

A painting of Mary Wollstonecraft by John Ople in 1797 (Source: Wikimedia)

Politically, the 18th century was a transformative period for England, marked by significant events that shaped the nation’s history. The War of American Independence, sparked by the poor policies of ministers like Grenville and Charles Townshend, as well as King George III’s support for these harsh policies, was a pivotal moment. The American defeat of British General Burgoyne in 1777 at Saratoga convinced France to join the Revolution, leading to the decisive British defeat at Yorktown in 1781. This victory not only secured American independence but also prompted calls for constitutional reform in England. However, it also had an unexpected consequence: England shifted its focus to expanding its overseas empire, acquiring territories in Canada, the Caribbean, Africa, and India.

SCOTLAND

The death of King William III, who was widowed and childless, left the crowns of both England and Scotland to his sister-in-law, Anne. Under pressure from restrictive trade policies imposed on Scotland, a treaty was negotiated that resulted in the formal union of the two countries in 1707, creating a single parliament. However, tensions remained. A Scottish proposal to build roads into the Highlands to exploit timber resources was rejected by the English, who preferred to import wood from their North American colonies. Furthermore, English coal could be exported duty-free to Ireland but not to Scotland. Poverty remained widespread, though the cultivation of the potato after 1739 and an increase in the breeding of black cattle provided some hope for economic recovery. In the Highlands, a warrior society persisted, with a tribal structure at the lower levels and a feudal-like hierarchy at the top. The Gaelic language remained widely spoken in these regions.

The Act of Union in 1707, which officially joined England and Scotland, did not extinguish Scottish national pride or prevent efforts to restore the Stuart monarchy. In 1745, Charles Edward Stuart, known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” the Catholic son of James Francis Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender), led the Jacobite Rebellion by invading England with an army of approximately 10,000 men. Despite early successes, the rebellion ultimately failed, culminating in the defeat of the Highlanders at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The aftermath was brutal: the English forces killed the wounded, executed fugitives, and burned homes in the Highlands. Following the defeat, the Highland clan system was dismantled, the playing of bagpipes in battle was banned, and wearing kilts was outlawed as part of the suppression of Gaelic culture. As a result of these repressive measures, many Celtic Scots, particularly those from the Highlands, emigrated to Nova Scotia (meaning “New Scotland”) and other parts of the British Empire. This marked the beginning of a significant Scottish diaspora, as many sought new opportunities and freedom from the hardships and persecution they faced at home.

A scene depicting Jacobites fighting against British regulars in the Battle of Culloden painted by David Morier, 1746 (Source: Wikimedia)

During the 18th century, Scotland experienced a remarkable transformation in education and intellectual pursuits. Every parish made efforts to establish a school for its children, significantly increasing access to education across the country. This commitment to learning was bolstered by the presence of four esteemed universities, which provided some of the finest education in the British Isles. The University of Edinburgh, in particular, thrived under the leadership of Alexander Monro, a student of the renowned Dutch botanist Hermann Boerhaave. Monro’s contributions helped establish Edinburgh as a leading center for medical instruction in the English-speaking world.

This period of intellectual flourishing is known as the “Scottish Enlightenment.” A distinguished group of thinkers emerged, profoundly influencing the fields of philosophy, history, economics, and literature. Philosophers David Hume and Thomas Reid laid the groundwork for empirical thought and philosophical inquiry, while historian William Robertson and political economist Adam Smith, author of “The Wealth of Nations,” made significant strides in their respective disciplines. Meanwhile, literary giants like Sir Walter Scott and the celebrated poet Robert Burns left an indelible mark on Scottish culture. Their works continue to resonate with audiences worldwide, reflecting Scotland’s rich heritage and distinct identity.

The Scottish Enlightenment fostered a spirit of inquiry and innovation that extended beyond academia, influencing social and political thought. This era not only shaped Scotland’s intellectual landscape but also contributed to broader discussions on governance, morality, and human rights, setting the stage for future movements in both Scotland and beyond. The legacy of this transformative period remains evident in contemporary scholarship and cultural expressions, highlighting Scotland’s pivotal role in the evolution of modern thought.

IRELAND

In 18th-century Ireland, the legacy of centuries-long English colonization and conflict had created a deeply divided society. The Irish population, predominantly Catholic, faced severe restrictions under the Penal Laws, enacted by the English Crown following the Williamite War (1689-1691) and reinforced after the Jacobite Rising of 1745. These laws prohibited Catholics from holding public office, restricted their access to education and professions, and limited their land ownership rights. Meanwhile, the Anglo-Irish Protestant ascendancy, comprising mostly English transplants, controlled vast estates and wielded significant political power. The Established (Anglican) Church in Ireland, representing only about one-seventh of the population, received state support through mandatory taxes levied on the peasantry, exacerbating sectarian tensions.

Socially, Ireland resembled eastern Europe and the southern American colonies, with a small elite class of wealthy landowners controlling vast tracts of land worked by a large number of poor, landless laborers. This oppressive environment, coupled with periodic famines and economic hardship, prompted many Irish to flee their homeland for the Americas. Between 1750 and 1800, an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the United States, with approximately 8,000 emigrating annually in the 1780s. Tensions boiled over in 1798 when the United Irishmen, inspired by the American and French Revolutions, launched a rebellion against British rule. Despite assistance from the French, the revolt was ultimately suppressed by Lord Cornwallis, marking a turning point in Anglo-Irish relations

A painting of Charles Carroll who was the only Irish Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence. He was the American-born son of Irish immigrants in the 1730s. (Source: Wikimedia)

In response to ongoing unrest and the threat of French invasion, English leaders sought to consolidate power and maintain control over Ireland through legislative union. The Act of Union, passed in 1800, formally united England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This move aimed to eliminate Irish parliamentary autonomy and ensure British dominance. However, the union failed to address underlying sectarian tensions and economic disparities, setting the stage for future conflicts, including Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation movement and the Irish Rebellion of 1803. As the 19th century unfolded, Ireland’s complex history would continue to shape its troubled relationship with Britain.

NORWAY

In the 18th century, Norway remained under Danish rule, yet it experienced significant developments that laid the groundwork for its future. The country rapidly expanded its shipping industry, becoming a key player in maritime trade, particularly with England. This growth was fueled by Norway’s rich natural resources, including timber and fish, which were in high demand across Europe. During this time, Ludvig Holberg emerged as Norway’s most notable literary figure, contributing to the cultural landscape with his comedies. Holberg’s works were performed in Denmark’s first theater, showcasing a blend of Norwegian and Danish influences and highlighting the evolving artistic expressions of the era. The burgeoning shipping industry and the flourishing of literature reflected Norway’s dynamic response to the complexities of its political situation and its aspirations for cultural identity during a century marked by change. This period set the stage for Norway’s eventual pursuit of greater autonomy and independence in the following centuries.

SWEDEN

After the conclusion of the Great Northern War (1700-1721), Sweden experienced a significant shift in political power toward the lower nobility and affluent merchants, who thrived in trade and industry. This newfound influence led to the parliament becoming the central hub of political life; however, as corruption among its leaders grew, public trust diminished. In response to this decline, Gustavus III (1746-1792) rose to power, reinstating an absolute monarchy during what became known as a golden age of intellectualism and the arts. This era saw a flourishing of cultural and scientific achievements, with notable figures such as Charles Linnaeus, who established the modern binomial system for naming plants and animals, and Anders Celsius, an astronomer at the University of Uppsala, who created the centigrade scale for temperature measurement. The work of these intellectuals not only advanced scientific understanding but also contributed to Sweden’s reputation as a center for enlightenment thought. As a result, the 18th century in Sweden became marked by a rich interplay of political change, cultural revival, and scientific progress, laying the foundation for future developments in both governance and society.

DENMARK

In 1699, Frederick IV (1671-1730) ascended to the throne of Denmark at the age of 28, marking the beginning of a reign that would significantly influence the country’s intellectual and industrial landscape. Frederick was a patron of the arts and learning, fostering an environment where intellectual life could thrive. His support extended to various industries, notably the establishment of the renowned Royal Copenhagen Porcelain factory, which became a symbol of Danish craftsmanship and artistry. After Frederick IV’s death in 1728, Denmark faced a tragedy when a devastating fire swept through Copenhagen during the reign of his successor, Christian VI (1730-1746). Christian VI continued the efforts to rebuild and improve the country but was also noted for his pious and somewhat austere rule.

Following Christian VI, Frederick V (1723-1766) took the throne and furthered Denmark’s connections with Britain by marrying the daughter of George II. After Frederick V’s death, Christian VII (1749-1808) ascended the throne, marrying Caroline Matilda, sister of George III of England. This period was characterized by increasing complexity in governance, as Christian VII struggled with mental health issues, leading to significant influence from his court. After 1784, his son, Frederick VI (1768-1839), implemented extensive reforms that transformed Danish society. These reforms included the liberation of peasants from serfdom, which facilitated the redistribution of land and the modernization of agricultural practices. In a groundbreaking move for the time, Denmark became the first European country to prohibit the slave trade in 1792, demonstrating a progressive shift in societal values and an emerging commitment to human rights that would influence future policies.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about Denmark’s involvement in the slave trade in the West Indies and its decision to abolish the trade in the article, “A Brief History of the Danish West Indies” |

FINLAND