32 PACIFIC OCEANIA

The Pacific Islands were home to thriving societies with complex systems of governance, agriculture, and trade. On Easter Island, the Rapa Nui people created a distinct culture, notable for their construction of over 1,000 monumental statues called moai. They also developed a tradition of craftsmanship, using totora reeds for building houses, boats, and furniture. The Rapa Nui’s rich tradition, including their monumental moai statues, reflects their complex social structure and cultural heritage. Similarly, the Māori had developed intricate social systems and agricultural practices in New Zealand. Pacific Islanders engaged in extensive trade and cultural exchanges across the region, fostering a diverse and interconnected cultural landscape.

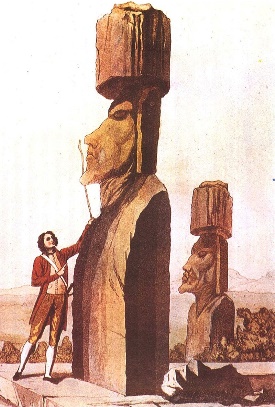

In this 18th century drawing, an explorer examines one of the moai on Easter Island (Source: Wikimedia)

In the 18th century, Pacific Islanders continued to explore and settle new lands. In New Zealand, the Māori population was estimated to be around 250,000. Both societies had developed unique cultures, with sophisticated systems of governance, agriculture, and spirituality. For thousands of years, Australia’s indigenous peoples, comprising over 250 distinct languages and more than 600 different clans and language groups, thrived on the continent. They had a deep connection to the land, with a rich cultural heritage and spiritual practices. Their societies were complex, with their own systems of governance, trade, and agriculture. However, with the arrival of the British in 1787, the lives of Australia’s indigenous peoples were forever changed. The British settlement at Sydney Cove marked the beginning of a long and complex history of colonization, displacement, and marginalization.

The British government’s decision to establish a penal colony in Australia brought significant disruption to the native populations. An estimated 700 convicts, mostly from urban areas of England, Ireland, and Scotland, were sent to Australia, forced to work in harsh conditions, clearing land and building infrastructure. While some convicts rebuilt their lives, others struggled. The legacy of British colonization and the convict era continues to impact Australia’s indigenous peoples, with ongoing struggles for land rights, cultural recognition, and social justice. Acknowledging and understanding this complex history is essential for reconciliation and a more equitable future for all Australians.

European explorers, including Jacob Roggeveen and Captain James Cook, arrived in the Pacific Islands during the mid-18th century. Their encounters with Pacific Island societies led to the establishment of trade and colonial relationships. However, this period also brought significant disruption to traditional ways of life, including the introduction of new diseases, technologies, and social structures that had lasting impacts on the islands’ cultures. The 18th century was marked by both the resilience of Pacific Island societies and the transformative effects of European exploration and colonization. Understanding the complex histories and cultures of Pacific Islanders provides a deeper appreciation of the region’s rich heritage and the ongoing legacies of colonialism.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn about the life and strange death of Captain Cook by watching Crash Course in History #27.

|