8 THE AMERICAS

The 16th century marked a significant turning point in the history of the Americas, as European explorers’ arrival brought far-reaching consequences for indigenous populations. However, it’s essential to acknowledge that European presence wasn’t the only significant factor in shaping the Americas during this period. Vibrant Native American, Maya, Aztec, and Inca cultures and civilizations thrived for centuries before Europeans arrived. In what is now the United States, diverse Native American communities like the Iroquois, Cherokee, and Navajo developed complex societies with their own systems of governance, agriculture, and trade. In Canada, indigenous peoples like the Cree, Ojibwe, and Mi’kmaq established thriving communities with rich traditions of storytelling, art, and spirituality. These societies developed sophisticated agricultural systems, architecture, art, and trade networks, and made significant advances in astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. The Maya developed a precise calendar system, while the Aztecs built a vast capital city, Tenochtitlán. The Inca constructed extensive road networks and terracing systems in the Andes. By the time Europeans arrived, these civilizations were already experiencing internal conflicts, migrations, and changes.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Caribbean initiated a wave of European exploration, but it was not a “discovery,” as the lands were already inhabited by diverse populations. By the early 1500s, European fishermen were fishing in Nova Scotia, and soon, they established trade relationships with indigenous peoples for furs and other valuable resources. The Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real arrived in Newfoundland, while French explorers Giovanni de Verrazano and Jacques Cartier mapped the eastern coast of North America, including the region now known as Canada. Other explorers, such as the Spanish conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, soon followed, leading to the colonization and devastation of many Native American communities.

NORTH AMERICA

At the beginning of the 16th century, North America was home to a staggering 40 million indigenous peoples, representing over 500 distinct languages and more than 2,000 separate nations. To put this number into perspective, the total population of Europe at that time was approximately 80-100 million people. This highlights the significant presence and diversity of indigenous cultures in North America, which would soon face unprecedented challenges with the arrival of European explorers and colonizers. These diverse populations exhibited remarkable variability in their social structures, systems of governance, economic practices, religious beliefs, technological innovations, historical experiences, and cultural traditions. Their economic activities were carefully adapted to the local environments, showcasing remarkable resourcefulness and ingenuity. Many engaged in skilled hunting and fishing practices, while others developed sophisticated agricultural systems, including irrigation techniques, to cultivate crops such as maize, beans, and squash. Some nations, like the Mississippian culture, built large, urban centers with complex earthen mounds, while others, like the Inuit, maintained small, kinship-based communities. Additionally, various groups employed nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles, migrating seasonally to optimize resource utilization. This incredible richness and diversity of indigenous cultures would soon face unprecedented challenges with the arrival of European explorers and colonizers.

This map shows the cultural regions of North America in the 16th century (Source: Wikimedia)

Extensive trading networks spanned North America, connecting diverse indigenous communities through roads and waterways. Major routes followed rivers like the Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Columbia, as well as coastal paths. One notable route ran along the Pacific Coast from northern Alaska to northwestern Mexico, with a branch traversing the Sonoran Desert to the Colorado Plateau. East of the Mississippi, roads linked towns in present-day Georgia and Alabama, with a significant route passing through Cherokee lands and the Cumberland Gap to the Ohio and Scioto Rivers. This network enabled travel from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas.

The complex road network fostered a shared cultural landscape, despite regional diversity. Common beliefs and values emphasized kinship, community, and consensus-based decision-making. Indigenous peoples identified themselves through family, community, and village ties, prioritizing collective interests over individual desires. This consensus-based system allowed for equal interactions among self-governing communities.

Most indigenous peoples in North America lived west of the Mississippi, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, where abundant resources supported thriving communities. The potlach ceremony, a gift-giving feast in which property was distributed to members of the community, emphasized reciprocity as a fundamental value. Skilled woodworkers, these communities created intricate totem poles and ceremonial masks. Notable nations included the Tinglit (Alaska) and salmon-fishing communities like the Salish, Makah, Hoopa, Pomo, Karok, and Yurok, who inhabited the coastal regions of present-day British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch this PBS Special to learn more about the wood-working traditions of the native peoples of the American Northwest.

|

At the beginning of the 16th century, the region now known as California boasted the highest Native American population density north of Mexico, with approximately one-third of all Native Americans in North America residing there. The region’s temperate climate and abundant food sources supported this large population. Notable nations in California included the Ohlone, Miwok, Modoc, Maidu, and Chumash, among others.

In the American Southwest, the Hohokam people built a sophisticated irrigation system, completed in the 15th century, which spanned over 800 miles of trunk lines and numerous branches serving local communities. This impressive network allowed for extensive agriculture, making the region a hub in a vast trade network stretching from Mexico to Utah and California to New Mexico.

On the Great Plains, Native American communities thrived, with some relying on agriculture and others on bison hunting. Notable nations included the Cree in Canada, the Lakota and Dakota Sioux in the Dakotas, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho to the west and south.

In the Southeast, indigenous peoples cultivated one of the world’s most fertile agricultural regions, relying on the “three sisters” – corn, squash, and beans – as their primary food source. They supplemented their diet with hunting and gathering, exploiting resources like deer and bears for food, skins, and oil. The region was home to many diverse tribes, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Apalachee, Caddo, Catawba, Chitimacha, Houma, Keyauwee, Koasati, Miccosukee, Natchez, Pamunkey, Powhatan Confederacy, Santee, Sewee, Shawnee, Timucua, Tuskegee, Tutelo, Waccamaw, and Yamasee. In present-day Virginia and the Carolinas, Algonquian-speaking peoples, including the Powhatan Confederacy and the Pamlico and Machapunga tribes, inhabited the region.

In the Northeast, the powerful Iroquois Confederacy (the Haudenosaunee). united various nations in present-day New York and the lower Great Lakes region. Their villages, often fortified and built away from waterways, featured corn, beans, and squash cultivation, as well as pottery for cooking and storing tobacco.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Visit this PBS website to learn more about how the Iroquois Confederacy may have

|

In general, life for Native American communities in the early decades of the 16th century was deeply rooted in their connection to the land and their spiritual beliefs. Many tribes believed in a complex spiritual system, which might include a single creator spirit, ancestral spirits, or spirits associated with natural elements and animals. Religious leaders, often shamans or spiritual leaders, played important roles in guiding communities and interpreting spiritual signs. Gender roles varied among tribes, but often women played significant roles, such as in the Iroquois Confederacy, where women controlled agriculture, food distribution, and diplomacy. Communities were often matrilineal, like the Huron-Wendat Nation, where property and social status passed through maternal lines. Native American life was rich with seasonal ceremonies, storytelling, and communal gatherings that reinforced social bonds and spiritual connections, reflecting the deep integration of cultural practices and communal life.

However, Native American communities experienced a profound shift in their way of life with the arrival of European explorers in the 16th century. For centuries, these communities had thrived, developing complex societies, cultivating the land, and honing their spiritual practices. Over time, the increasing presence of outsiders brought unprecedented challenges, disruptions, and transformations, including the introduction of new technologies, diseases, and ideas that would forever alter the course of Native American history. As European exploration and settlement expanded, Native American communities faced significant changes to their lands, cultures, and ways of life, leading to a period of significant upheaval and transformation. This process unfolded differently across various regions and communities, with some experiencing early and intense impacts, while others faced later and more gradual changes, shaped by factors like geography, tribal politics, and the specific interests of European powers. However, despite the diverse experiences and timelines of European contact, all Native Americans in the Americas shared a common fate: the loss of land, cultural suppression, and the erasure of their identities. The cumulative effects of colonization, forced relocation, and violence resulted in significant population decline, cultural disruption, and intergenerational trauma.

The colonization of North America, which would ultimately lead to such devastating consequences, began with the arrival of Spanish explorers in the early 16th century. Spain was the first European nation to colonize North America, with an expedition led by Juan Ponce de León landing in Florida in 1513. Ponce de León, a veteran of Christopher Columbus’ second voyage, claimed the region for Spain, marking the beginning of European colonization. Throughout the 16th century, numerous European ships wrecked along the southern coast of North America, scattering silver coins and jewelry that Native Americans repurposed into pendants, necklaces, and beads. As a result, coastal Native American communities acquired knowledge about Europeans and their material culture before direct contact, giving them a unique perspective on the newcomers.

A 17th century engraving of Ponce de León (Source: Wikimedia)

In 1539, Hernando de Soto’s arrival in present-day Tampa Bay, Florida, marked the beginning of a catastrophic encounter between European explorers and Native American societies. De Soto’s expedition, comprising 600 men and over 200 horses, traversed the peninsula, culminating in an encounter with the formidable Queen of Cofitachequi in present-day South Carolina. Despite her kingdom’s impressive grandeur, showcased by the queen’s court adorned in elaborate pearl necklaces and her warriors’ arsenal of copper-tipped weapons and thousands of bows and arrows, De Soto’s presence unleashed a devastating and insidious threat: diseases from Europe, such as smallpox, measles, and influenza, which would ravage the indigenous population and irreparably dismantle the economic and political structures of Mississippian society, exposing the limitations of even the Queen’s considerable wealth and power. De Soto’s journey continued westward, ultimately ending in his death and burial in Arkansas.

Concurrently, Vasquez de Coronado commissioned Friar Fray Marcos to explore present-day New Mexico in 1539. The following year, Coronado led an expedition in search of the mythical “Seven Cities of Gold,” reaching the vicinity of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and then venturing into the Texas Panhandle, Kansas, and the Nebraska border. On his return journey, Coronado launched a brutal attack on the Acoma Indian city, killing 600 people and enslaving many more over the course of three days. Later, in 1596, Juan de Onate led an expedition from Mexico City to El Paso, Santa Fe, and Quivera (Kansas), followed by the arrival of over 400 Spanish settlers and their livestock in New Mexico in 1598.

A view of the Acoma Pueblo mesa from the northwest The Acoma pueblo, originally built by Kersan Indians on top of this mesa, had buildings that were 3 stories high. It may be the oldest inhabited site in the United States. (Source: Creative Commons)

MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA, AND THE CARIBBEAN

In the early 16th century, the Aztec Empire in modern-day Mexico was experiencing a surge in political and military power, while the Inca Empire in present-day Peru had reached its peak, boasting a sophisticated and affluent society. The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, was a thriving metropolis with over 60,000 households, and the empire’s total population is estimated to have exceeded 30 million people. Similarly, the Inca Empire was densely populated, with a strong focus on agriculture. The indigenous American crops of corn (maize) and potatoes proved to be highly caloric, surpassing the nutritional value of most Eurasian crops, except for rice. This allowed for a remarkable population density, with some areas reaching levels comparable to those found in the East Asian rice-paddy regions. In fact, the Aztec and Inca Empires were among the most populous and complex societies in the Ancient Americas, with sophisticated systems of governance, architecture, and engineering.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Take a stroll around an Aztec Zoo in 16th century Tenochtitlan.

|

Columbus and those who followed started a great exchange of foods. Wheat, chick-peas, sugarcane, pigs, cows, and sheep were brought from Europe to the Americas. Europeans took corn, potatoes, chocolate, peanuts, vanilla, tomatoes, pineapples, lima beans, peppers (both red and green), tapioca, and the turkey back to Europe. This exchange of foods is part of what historians have called “The Columbian Exchange.”

European exploration of the Americas connected four continents (Africa, North America, South America, and Europe) in a network of communication, migration, trade, disease, and the transfer of both animals and plants. The long-term effects of this network benefited Europeans to the detriment of both Africans and Native Americans. The indigenous peoples of Africa and the Americas suffered intensely as slavery, disease, and death on an almost unimaginable scale destroyed their societies while Europeans reaped the rewards of this exchange. Europeans were enriched by the abundance of natural resources taken from the Americas. Precious metals (especially silver), new food crops, financial profits, and new markets provided the necessary foundation for the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century.

The impact of this exchange reached far beyond goods. As new information about peoples and places that had previously been unknown circulated through European societies, people began to question what they had been taught. People asked new questions and discovered new ways of thinking. These new thoughts and patterns expressed themselves in the 17th century in what is called the “Enlightenment.” The Columbian Exchange, therefore, contributed to a shift in global power leading to the emergence of Europe as a dominant player in the world (militarily and economically).

The Columbian Exchange was a significant event in history that had both positive and negative effects. To understand it fully, we need to engage in perspective-taking, considering the different viewpoints of the people involved, including European explorers, African slaves, and Native American communities. By doing so, we can gain a more complete understanding of what happened and why. Perspective-taking helps us move beyond a simple “good” or “bad” judgment and instead see the complexity of historical events, acknowledging the diverse experiences and motivations that shaped this pivotal moment in world history. By doing so, we can unravel the complex web of motivations, causes, and consequences that shaped this event. Through this nuanced approach, we can move beyond binary narratives and instead embrace the multifaceted nature of historical events, acknowledging both the accomplishments and the atrocities that have shaped our shared human experience.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

To learn more about the Columbian Exchange, watch Crash Course in World History #23.

|

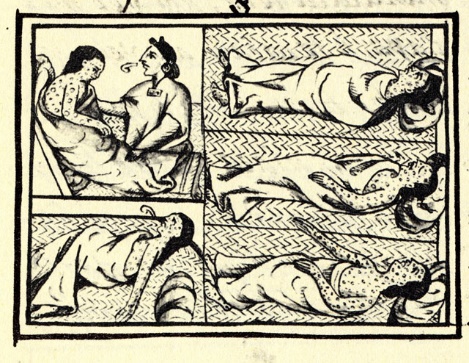

In 1521, the Aztec Empire, led by King Montezuma II, was devastated by the arrival of Hernando Cortéz and his small contingent of Spanish conquistadors. However, it was not solely the Spanish military might that led to the downfall of the Aztecs. The introduction of European diseases, such as smallpox and measles, to which the native population had no immunity, proved to be a far more destructive force. These diseases spread rapidly, killing an estimated 90% of the population, leading to a demographic catastrophe that eclipsed the impact of military conquest. This tragic event was part of a broader pattern of European contact with native populations, where disease and displacement led to widespread devastation

A drawing accompanying text in Book XII of the 16th-century Florentine Codex (compiled 1555–1576), showing native peoples afflicted with smallpox (Source: Creative Commons)

Within two decades of their arrival in Mexico, the Spanish explored the Americas from coast to coast and established a vast empire. They imposed their own civilization, introducing European customs, language, and religion. Alongside the Portuguese, they also brought slavery to the Americas. By the mid-16th century, thousands of African slaves had been brought to Mexico and South America. The Spanish discovered rich silver deposits in Mexico and South America, with the Bolivian mines producing nearly 85% of the world’s silver in the 16th century. This silver wealth financed the Spanish Empire, accounting for approximately one-fifth of their budget. Without it, the Spanish would not have maintained their maritime empire or strengthened their position among European nations.

In the Caribbean, Spanish settlers in Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) exploited African slaves and native peoples on plantations. They also kidnapped Arawak Indians from the Bahamas for slave labor and transported thousands of Native Americans from the United States to the West Indies. However, as smallpox decimated indigenous populations in 1519, the Spanish shifted their reliance from native slaves to African slaves. The high mortality rate among Native American slaves led to a growing dependence on African labor. This had the devastating consequence of introducing new diseases that affected native populations. By the end of the century, African slaves and Europeans had largely replaced the indigenous population in the Caribbean.

This map shows the 16th century Spanish conquests in the Caribbean and Latin America. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

To learn more about the Spanish Empire’s colonization of the Americas, watch Crash Course in World History #25. |

SOUTH AMERICA

In 1501, the Spanish arrived in South America, making landfall on the coasts of what is now Colombia, specifically in the areas around the Bay of Santa Marta and the Gulf of Cartagena. This marked the beginning of their encounters with the indigenous Tairona people, who lived in the region. The Spanish interactions with the Tairona were often characterized by violence and conflict. Spanish accounts describe the Tairona as inhabiting a 90-mile coastal strip at elevations below 3,300 feet, where they practiced advanced gold metallurgy. Despite these encounters, the Spanish never fully subdued the Tairona region. The Tairona people retreated to the mountains to escape Spanish advances. Over time, their presence diminished from historical records, likely due to the impacts of disease, hunger, and displacement caused by the Spanish incursions. Archaeological excavations have revealed remnants of Tairona settlements, including impressive stone structures, roads, paved stairways (some up to 60 feet wide), and stone block bridges. These sites also feature rock carvings, agricultural terraces, and artificial mounds used for ceremonial purposes, showcasing the advanced nature of Tairona society.

Tairona figure pendants in gold (Source: Wikimedia)

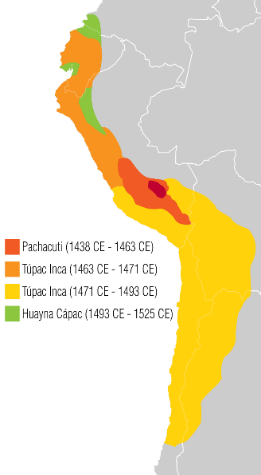

At the time of European arrival, parts of South America, like Mexico, were densely populated. The Inca Empire, situated in the Andean mountains, was home to approximately 12-18 million people. Their diet was primarily vegetarian, consisting of crops like maize, potatoes, squash, beans, and manioc. They also raised guinea pigs and ducks, and occasionally hunted game like deer and llamas. Fish was a rare addition to their diet.

Tragically, the smallpox virus introduced by the Spaniards spread rapidly, decimating the Inca population and causing widespread death and destruction. The Inca leader, Huayna Capac, died of the disease in 1527, triggering a devastating civil war between his two sons, Atahualpa and Huascar. Amidst this chaos, Francisco Pizarro arrived in 1531 with his soldiers and horses, leading to a rapid deterioration in relations between the Spanish and Inca. By 1533, the situation had become unbearable for the Inca, marking the beginning of the end of their empire.

In the 1530s, Spanish conquistadores, driven by the lure of gold, ventured into the northern region of South America. Sebastian de Belalcázar, a seasoned explorer and founder of Quito, Ecuador, heard tales of a king who covered himself in gold dust before bathing in a sacred lake. This legend spawned the myth of “El Dorado – the Golden Man,” fueling the Spanish obsession with gold. In 1536, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada led an expedition from Colombia’s northern coast, but only 200 of his 900 men survived the treacherous journey, ravaged by disease, malaria, and native resistance. Although he didn’t find gold, Quesada founded the city of Santa Fe de Bogotá, now Colombia’s capital.

Other explorers, including German Nikolaus Federmann, Spanish conquistadors Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orellana, and English adventurer Sir Walter Raleigh, also scoured the region for gold. Orellana’s 1542 expedition led him to discover the Amazon River, where he encountered a tribe with skilled female archers, reminiscent of the ancient Greek legend of the Amazons. As the century drew to a close, the quest for gold shifted to Guiana and Trinidad, where Spanish and English explorers, including Sir Walter Raleigh, converged in pursuit of the precious metal.

This map shows the extension of the Inca Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries. (Source: Creative Commons)

The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, an agreement between Spain and Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside of Europe. A line was drawn on the map, running north-south through the Atlantic Ocean, allocating the lands west of the line to Spain and the lands east of the line to Portugal. This treaty shaped the colonization of the Americas and the global empires of Spain and Portugal.

As a result, Spain gained most of the Americas, while the eastern part of present-day Brazil, extending into the Atlantic, fell under Portuguese control. In 1500-1502, Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral charted Brazil’s coasts, naming the land after the valuable pau-brasil wood. This wood was highly prized for its deep red dye, used to color luxurious fabrics, making it a sought-after commodity in Europe. The Portuguese named the new land “Brazil” after this valuable resource.

Colonization began in 1534 when King João III divided the coastline into fifteen sections, granting them to donatários (landowners) who could establish cities, distribute land, and collect taxes. These donatários were responsible for colonizing and developing their allocated lands, but the system ultimately proved flawed, as some owners never arrived, and others lacked capital. By the 1540s, only two sections had succeeded, prompting royal takeover. The first governor-general arrived in Bahia (now Salvador) in 1549, and the capital remained there until 1763.

Alongside the governor, colonists and Jesuit missionaries arrived. Most immigrants were young, single men who had worked as artisans or laborers. Few families came initially, causing a significant gender imbalance until the 18th century. Jesuits, led by prominent priests like Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta, ventured inland to convert Native Americans to Christianity. However, they clashed with Portuguese settlers, explorers, and adventurers, known as bandeirantes, who were searching for gold and silver. The bandeirantes‘ brutal treatment of Native Americans and their focus on exploiting resources conflicted with the Jesuits’ mission to protect and convert the indigenous population. This led to tensions and conflicts between the two groups, with the Jesuits advocating for Native American rights and the bandeirantes prioritizing their own economic interests

As Portuguese explorers and settlers ventured further inland, they expanded Brazil’s original borders, established by the Treaty of Tordesillas. By the late 1600s, they had occupied the entire Amazon River basin, reaching the Andes Mountains, and moved south to the Rio de la Plata, now the border between Argentina and Uruguay. This led to a century of border disputes between the Spanish and Portuguese.

Portuguese colonization was accompanied by widespread missionary work, aiming to convert Native Americans to Christianity. Three main Catholic orders – the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Jesuits – joined the colonizers. One notable example is José de Anchieta (1534-1597), a Portuguese Jesuit priest who advocated for Native American rights and worked to protect them from exploitation. He also played a key role in establishing missions and converting Native Americans to Christianity.

While José de Anchieta’s efforts in Brazil represented a more benevolent aspect of missionary work, the harsh realities of colonialism were not unique to the Portuguese colonies. Across the Spanish Americas, similar patterns of exploitation and violence were unfolding. One voice that emerged to condemn these atrocities was that of Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), a Spanish priest who witnessed firsthand the devastating impact of colonialism on Native American populations. De las Casas’ writings, such as “A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies” (1542), offer a powerful indictment of colonialism and a call to action for reform.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

In the following passage, Bartolomé de Las Casas describes some of the abuses carried out by Spanish soldiers against native peoples: This was the first land in the New World to be destroyed and depopulated by the Christians, and here they began their subjection of the women and children, taking them away from the Indians to use them and ill use them, eating the food they provided with their sweat and toil. And they committed other acts of force and violence and oppression which made the Indians realize that these men had not come from Heaven. And some of the Indians concealed their foods while others concealed their wives and children and still others fled to the mountains to avoid the terrible transactions of the Christians. And the Christians attacked them with buffets and beatings, until finally they laid hands on the nobles of the villages. Then they behaved with such temerity and shamelessness that the most powerful ruler of the islands had to see his own wife raped by a Christian officer. And the Christians, with their horses and swords and pikes began to carry out massacres and strange cruelties against them. They attacked the towns and spared neither the children nor the aged nor pregnant women nor women in childbed, not only stabbing them and dismembering them but cutting them to pieces as if dealing with sheep in the slaughter house. They laid bets as to who, with one stroke of the sword, could split a man in two or could cut off his head or spill out his entrails with a single stroke of the pike. They took infants from their mothers’ breasts, snatching them by the legs and pitching them headfirst against the crags or snatched them by the arms and threw them into the rivers, roaring with laughter and saying as the babies fell into the water, ‘Boil there, you offspring of the devil!’ Read a longer excerpt of de Las Casas’ writings (from which this passage was taken).

A Portrait of Bartolomé de Las Casa by an unknown artist (Source: Wikimedia) |

|

Sugar cane was introduced to Brazil in the early 16th century, and by 1550, sugar mills were operational, marking the beginning of the sugar plantation system. This system revolutionized the Brazilian economy, making it a major player in the global sugar market. Between 1575 and 1600, coastal Brazil emerged as a leading sugar producer, with sugar production driving economic growth. The sugar industry’s growth had a ripple effect, leading to the expansion of commercial activities. Shops began to appear on the streets of São Paulo, and Portuguese merchants established themselves as shopkeepers and peddlers throughout Spanish America after 1580. This influx of merchants helped to establish a thriving commercial network, further solidifying Brazil’s position as a major economic power.

However, the sugar plantation system’s success came at a devastating cost. At first, the Portuguese attempted to enslave native peoples, but their efforts were met with resistance and evasion. Native peoples in Brazil had a deep understanding of the land, allowing them to evade capture and resist enslavement by European colonizers. Their knowledge of the terrain and ability to navigate the dense forests and rugged terrain made it challenging for colonizers to track and subdue them. As a result, European colonizers turned to the transatlantic slave trade, forcibly bringing millions of enslaved Africans to Brazil on Spanish and Portuguese slave ships, who were then forced to work on sugar plantations and other agricultural endeavors. By the late 16th century, the transatlantic slave trade had significantly altered the demographic landscape of Brazil, with tens of thousands of enslaved Africans being brought to the region. This influx of enslaved Africans was driven by the expansion of sugar plantations and the need for labor. The transatlantic slave trade played a crucial role in shaping Brazil’s demographic and social structure, with African slaves becoming a major component of the labor force and contributing to the country’s cultural and social development

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the sugar industry in 16th century Brazil by visiting this web-page.

|

For thousands of years, various indigenous groups inhabited the region that is now Argentina, including the Guarani, Quechua, and Tehuelche peoples, each with their own distinct cultures and traditions. These native populations developed complex societies, harnessed the region’s natural resources, and built thriving communities long before the arrival of European explorers.

Present-day Argentina was first encountered by Europeans in 1516, when the Spanish explorer Juan Diaz de Solis arrived on its shores. This initial contact was followed by further exploration of the coasts by Diego Garcia in 1526, marking the beginning of European interest in the region. The first attempt to establish a permanent settlement was made in 1534, when Pedro de Mendoza founded the city of Buenos Aires. However, this early village struggled to survive and eventually died out or was destroyed, leaving the region without a European presence for several decades.

It wasn’t until 1580 that the Portuguese rebuilt the city of Buenos Aires, establishing a thriving trade hub that would shape the region’s economy and culture. Portuguese ships arrived in Buenos Aires laden with a variety of goods, including rice, fabrics, black slaves, and occasionally gold. From there, they traveled up the Rio de la Plata, exchanging these goods for silver that was transported down the Pilcomayo River. This lucrative trade network brought significant prosperity to the region, cementing Buenos Aires’ position as a key commercial center in South America. The city’s strategic location and access to valuable resources made it an attractive destination for European colonizers, setting the stage for further growth and development in the centuries to come.