26 THE MIDDLE EAST

ARABIA AND JORDAN

In the 18th century, the Middle East was a rich mosaic of cultures, languages, and empires, all under the overarching influence of Ottoman rule. A common desire for greater autonomy united various Arab leaders and reformers, each envisioning a different future for the region. One significant figure was Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792), a scholar from the Najd region of Arabia who promoted a strict, literalist interpretation of Islam. Wahhab condemned Shia and Sufi practices as deviations from orthodox Islam, targeting rituals such as the veneration of saints and the celebration of Ashura, which he viewed as idolatrous. His teachings emphasized the oneness of God (tawhid) and rejected practices he deemed as contrary to his vision of Islamic purity. Wahhab’s ideology laid the groundwork for a conservative Islamic state, though its history would later involve conflict and controversies, particularly in its treatment of Shia and Sufi communities.

Intercultural Competency and the Legacy of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792) exemplifies how rigid and intolerant interpretations of religion can lead to significant sectarianism and conflict. His strict, literalist approach to Islam led him to reject Shia and Sufi practices, viewing them as idolatrous and contrary to his interpretation of Islamic orthodoxy. This rejection of diverse Islamic traditions and cultural expressions contributed to sectarian divisions and tensions. Wahhab’s teachings, while rooted in his own understanding of Islamic purity, had profound and often controversial impacts, including acts of violence and coercion against minority groups. His legacy highlights the complexities and potential consequences of religious and cultural intolerance, serving as a reminder of the importance of fostering empathy, understanding, and inclusive dialogue, particularly in diverse and intercultural contexts. While Wahhab’s approach was shaped by his historical and theological context, his example underscores the need for sensitivity and respect for differing perspectives within any cultural or religious discourse.

In 1740, Muhammad ibn Saud, a local ruler from the Al Saud family, allied with Wahhab, leading to the expansion of their control over central Arabia. This alliance established a state rooted in Wahhabi principles, which would later influence the formation of modern Saudi Arabia. By the end of the 18th century, the foundations were set for a state that would evolve into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The legacy of Wahhab and Ibn Saud continues to impact Islamic thought and politics, contributing to ongoing discussions about extremism, sectarianism, and human rights, especially in relation to minority groups within the region.

A map showing the geographical growth of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 18th century. (Source: Wikimedia)

PERSIA (IRAN)

In the 18th century, Persia faced significant political challenges due to aggressive neighbors: the Afghans to the east, the Ottomans to the west, and the Russians to the north. Despite these difficulties, Persia maintained a robust trade network. A 1708 document indicates that camels transported large loads, up to 1,500 pounds, between Tabriz in northwestern Persia and Istanbul, highlighting the significance of trade in the region.

Persia’s political instability was marked by the Afghan leader Mahmud (1722-1725), who defeated the central Persian army in 1722 and briefly ruled Persia. Mahmud’s reign was characterized by the harsh treatment of Persian leaders, including the massacre of nobles and princes. The Russians and Ottomans sought to exploit Persia’s weakness, but Nadir Shah (1688-1747) played a crucial role in defending the country. With temporary Russian support, Nadir Shah defeated the Afghans and the Ottomans and declared himself Shah in 1736, initiating a period of relative stability under his rule. This pattern of seeking and receiving Russian support against regional rivals like the Afghans and Ottomans would recur throughout Persian history, as Persia often found itself aligned with Russia to counterbalance external threats.

A portrait of Agha Mohammad 1 (Source: Wikimedia)

For ordinary people in 18th century Persia, life was marked by economic struggle, religious devotion, and traditional family structures. Many lived in rural areas, working as farmers or herders, while others resided in cities like Tabriz and Isfahan, engaging in trade and commerce. The economy was largely agrarian, with most people living off the land. Religious life was deeply influenced by Shia Islam, with daily prayers, fasting during Ramadan, and pilgrimages to holy sites like Mashhad. Family life was patriarchal, with men holding authority over women and children. Women’s roles were largely confined to the home, where they managed household chores and raised children. Gender segregation was prevalent, with women wearing veils and living in separate quarters. Despite these social constraints, women played important roles in family decision-making and religious observance. Overall, life for ordinary people in 18th century Persia was shaped by a complex interplay of economic, religious, and social factors.

The late 18th century saw the rise of the Qajar Dynasty, founded by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar (1742-1797). Agha Mohammad Khan’s reign was marked by significant achievements, including the reassertion of central authority and the relocation of the capital to Tehran, which laid the foundation for the modern state of Iran. However, his methods were often severe. His rule involved harsh measures to consolidate power, including military campaigns and the suppression of opposition. Notably, his actions in Georgia were marked by severe measures, with the massacre of many inhabitants and the forced relocation of around 15,000 people.

Despite his harsh tactics, Agha Mohammad Khan’s leadership was instrumental in stabilizing Persia after a long period of fragmentation and turmoil. His reign saw the reestablishment of a centralized administration, which helped to restore order and strengthen the state. His assassination in 1797 ended a tumultuous era, but his efforts left a lasting impact on the region’s political landscape. At the century’s close, a treaty with the British East India Company was signed, pledging British support against potential threats from Afghanistan or France, setting the stage for future geopolitical maneuvering in the region. This recurring pattern of aligning with external powers for protection against regional rivals underscores the complex and often precarious nature of Persia’s geopolitical strategy.

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

The Ottoman Empire’s military prowess was prominently displayed in November 1710 when it declared war on Russia and marched north from Adrianople (modern-day Edirne), an important Ottoman city in present-day Turkey. The Ottoman army, bolstered by Tatar cavalry, swelled to 200,000 men under the command of Grand Vizier Damad Ibrahim Pasha (c. 1660-1730), which forced Peter the Great (1672-1725) to negotiate the Treaty of the Pruth (1711). This conflict underscored the Ottoman Empire’s central role in the Islamic world, with its heartland in Anatolia (Turkey) exerting influence over much of the Arab world, Egypt, North Africa, and the Christian populations in the Balkans.

However, the 18th century also brought significant challenges for the Ottoman Empire, including conflicts with Persia and Russia. The Ottomans faced defeats in various conflicts, notably with Russia under Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796). By the end of the century, Russia had secured substantial territorial concessions around the Black Sea and in the eastern Balkans. The Ottomans progressively lost control of regions such as Hungary, the Banat, Transylvania, Bukovina, and eventually the Crimea, which was ceded to Russia in 1783 following the Treaty of Jassy. As their military power declined, the Ottomans increasingly relied on diplomacy to preserve their prestige.

Despite these challenges, the Ottoman Empire remained a complex and multifaceted society. At its core was the Sultan, such as Ahmed I (1590-1617), who held the title of caliph, claiming succession from the Prophet Muhammad and regarded as the leader and defender of Muslims. The empire’s administrative and military systems were highly developed, featuring a sophisticated network of officials, soldiers, and spies. However, this complexity also led to opportunities for corruption and abuse of power.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Review the history of the Ottoman Empire by watching Part 3 of the PBS special, Islam: Empire of Faith.

|

For ordinary people living in the Ottoman Empire, life was shaped by a complex interplay of economic, religious, and social factors. Muslims, the majority population, followed Islamic traditions and practices, with daily prayers, fasting during Ramadan, and pilgrimages to holy sites like Mecca. The empire’s Muslims included Turks, Arabs, Persians, and others, each with their own cultural and linguistic identities. Alongside Muslims, thousands of non-Muslims, including Christians, Jews, and others, lived in the empire, with varying degrees of autonomy and protection. Christians and Jews, classified as dhimmi (protected peoples), faced certain restrictions and taxes, but were also granted freedom to practice their faiths and manage their community affairs. Many non-Muslims thrived in trade and commerce, and some even rose to prominent positions in government and society. In vibrant cities like Istanbul, Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others lived together, with mosques, churches, and synagogues standing alongside bustling markets and bazaars, reflecting the empire’s rich cultural diversity.

As the Ottoman Empire declined, new groups emerged with increased influence, including the Phanariots, a Greek Orthodox elite who lived in the Phanar district of Istanbul (formerly known as Constantinople). The Phanariots, largely comprised of Greek Christian families, gained significant power in the Ottoman administrative structure, serving in high-ranking positions such as dragomans (interpreters) and provincial governorships. Their influence was partly due to their role in the administration of the empire and their connections with the Ottoman court.

The Phanariots played a significant role in the administration of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Constantinople. During this period, the Patriarchate increased its influence over the Orthodox Christian communities in the Ottoman Empire, including those in Serbia and Bulgaria. However, this influence was complex and not merely an extension of jurisdiction; it involved negotiations and accommodations within the broader framework of Ottoman rule. The Serbian and Bulgarian Orthodox churches had their own local hierarchies and administrative structures, and their relationship with the Patriarchate of Constantinople was mediated through various political and religious negotiations. Overall, the Phanariot families contributed to the changing power dynamics within the Ottoman Empire, reflecting the empire’s increasingly complex internal structure as it faced external pressures and internal challenges.

ARMENIA

In 18th-century Armenia, the majority of the population was Christian, with the Armenian Apostolic Church playing a central role in religious and cultural life. Their adherence to Miaphysitism, a doctrine that holds Christ has one united nature that is both divine and human, set them apart from the Chalcedonian orthodoxy of Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism, which defines Christ as having two distinct natures, one divine and one human. This theological distinction, combined with their geographical location surrounded by Muslim nations, further exacerbated their separation from the broader Christian world. Despite facing restrictions and persecution under Ottoman rule, Armenian Christians maintained their distinct identity and traditions. The church served as a vital institution, providing spiritual guidance, education, and community support. Armenian clergy and monks played important roles in preserving and promoting Armenian culture, including literature, art, and architecture.

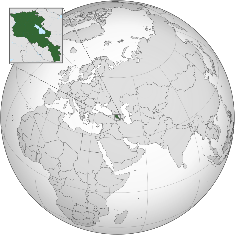

Armenia Location (Source: Wikimedia)

Armenian merchants and financiers were also prominent figures in the Ottoman economy, traveling extensively throughout the empire and beyond. Some Armenian merchants engaged in trade as far away as the Chinese frontier, while others established trade routes with cities in India. In Istanbul and other Ottoman cities, Armenian businessmen were respected for their expertise and networks, facilitating commerce and finance across the empire. Despite facing challenges and discrimination, the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire maintained a strong sense of identity and culture, with their religious traditions and practices serving as a vital connection to their heritage.