43 SOUTH AMERICA

From 1815 to 1822, there was an amazing eruption of new nations in South America. Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín led the final phase of the independence struggle in the Americas that had begun in 1776 with the writing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who played a key role in the establishment of Venezuela, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Panama as sovereign states independent of Spanish rule. Bolívar was born into a wealthy, aristocratic Creole family and like others of his day was educated abroad at a young age, arriving in Spain when he was 16 and later moving to France. While in Europe, he was introduced to the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers, which gave him the ambition to replace the Spanish as rulers. Taking advantage of the disorder in Spain prompted by the Peninsular War, Bolívar began his campaign for Venezuelan independence in 1808, appealing to the wealthy Creole population through a conservative process, and established an organized national congress within three years. Despite a number of hindrances, including the arrival of an unprecedentedly large Spanish expeditionary force, the revolutionaries eventually prevailed, culminating in a patriot victory at the Battle of Carabobo in 1821 that effectively made Venezuela an independent country.

This map shows the area of Gran Colombia claimed by Bolivar (Source: Wikimedia)

Following this triumph over the Spanish monarchy, Bolívar participated in the foundation of the first union of independent nations in Latin America, Gran Colombia, of which he was president from 1819 to 1830. Through further military campaigns, he ousted Spanish rulers from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia (which was named after him). He was simultaneously president of Gran Colombia (current Venezuela, Colombia, Panamá, and Ecuador) and Peru, while his second in command Antonio José de Sucre was appointed president of Bolivia. He aimed at a strong and united Spanish America able to cope not only with the threats emanating from Spain and the European Holy Alliance but also with the emerging power of the United States. At the peak of his power, Bolívar ruled over a vast territory from the Argentine border to the Caribbean Sea.

In his twenty-one-year career, Bolívar faced two main challenges. First was gaining acceptance as undisputed leader of the republican cause. Despite claiming such a role since 1813, he began to achieve acceptance only in 1817, and consolidated his hold on power after his dramatic and unexpected victory in New Granada in 1819. His second challenge was implementing a vision to unify the region into one large state, which he believed would be the only guarantee of maintaining American independence from the Spanish in northern South America. His early experiences under the First Venezuelan Republic and in New Granada convinced him that divisions among republicans, augmented by federal forms of government, only allowed Spanish American royalists to eventually gain the upper hand. Once again, it was his victory in 1819 that gave him the leverage to bring about the creation of a unified state, Gran Colombia, with which to oppose the Spanish Monarchy on the continent.

At the end of the wars of independence (1808–1825), many new sovereign states emerged in the Americas from the former Spanish colonies. Throughout this revolutionary era, Bolívar envisioned various unions that would ensure the independence of Spanish America vis-à-vis the European powers—in particular, Britain—and the expanding United States. Already in his 1815 Cartagena Manifesto, Bolívar advocated that the Spanish American provinces should present a united front to the Spanish in order to prevent being re-conquered piecemeal, though he did not yet propose a political union of any kind. During the wars of independence, the fight against Spain was marked by an incipient sense of nationalism. It was unclear what the new states that replaced the Spanish Monarchy should be. Most of those who fought for independence identified with both their birth provinces and Spanish America as a whole, both of which they referred to as their patria, a term roughly translated as “fatherland” and “homeland.”

For Bolivar, Hispanic America was the fatherland. He dreamed of a united Spanish America and in the pursuit of that purpose not only created Gran Colombia but also the Confederation of the Andes, which was to gather the latter together with Peru and Bolivia. Moreover, he envisaged and promoted a network of treaties that would hold together the newly liberated Hispanic American countries. Nonetheless, he was unable to control the centrifugal process that pushed in all directions. He thus ultimately failed in his attempt to prevent the collapse of the union. Gran Colombia was dissolved later that year and replaced by the republics of Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador.

Although Bolívar attempted to keep the Spanish-speaking parts of the continent politically unified, they rapidly became independent of one another as well, and several further wars were fought, such as the Paraguayan War and the War of the Pacific. At the time, there was discussion of creating a regional state or confederation of Latin American nations to protect the area’s newly won autonomy. After several projects failed, the issue was not taken up again until the late 19th century.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

On January 20, 1830, as his dream fell apart, Bolívar delivered his last address to the nation, announcing that he would be stepping down from the presidency of Gran Colombia. In his speech, a distraught Bolívar urged the people to maintain the union and to be wary of the intentions of those who advocated for separation. Note that at the time, “Colombians” referred to the people of Gran Colombia (Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador), not modern-day Colombia. Colombians! Today I cease to govern you. I have served you for twenty years as soldier and leader. During this long period we have taken back our country, liberated three republics, fomented many civil wars, and four times I have returned to the people their omnipotence, convening personally four constitutional congresses. These services were inspired by your virtues, your courage, and your patriotism; mine is the great privilege of having governed you… Colombians! Gather around the constitutional congress. It represents the wisdom of the nation, the legitimate hope of the people, and the final point of reunion of the patriots. Its sovereign decrees will determine our lives, the happiness of the Republic, and the glory of Colombia. If dire circumstances should cause you to abandon it, there will be no health for the country, and you will drown in the ocean of anarchy, leaving as your children’s legacy nothing but crime, blood, and death…. Fellow Countrymen! Hear my final plea as I end my political career; in the name of Colombia I ask you, beg you, to remain united, lest you become the assassins of the country and your own executioners. You can read more of Bolivar’s writings in El Libertador edited by David Bushnell. |

|

The second important independence leader was Jose de San Martin who commanded crucial military campaigns that led to independence for Argentina, Chile, and Peru. San Martín is regarded as a national hero of Argentina and Peru, and together with Bolívar, one of the Liberators of Spanish South America. The Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Orden del Libertador General San Martín), created in his honor, is the highest decoration conferred by the Argentine government.

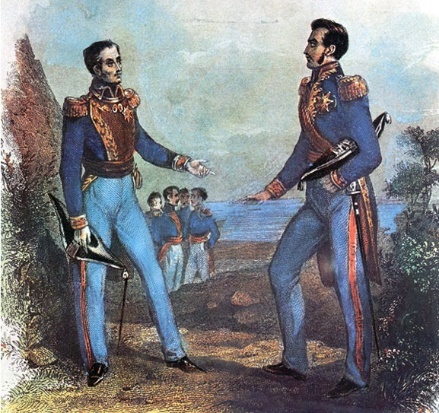

A painting of a meeting between the two important South American independence leaders. Martin is the figure to the left and Bolivar is the figure to the right. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch John Green explain why Bolivar was unable to create a unified South American nation in Crash Course in World History #225.

|

Chile was organized as a democratic republic under the son of an Irish officer, Bernardo O’Higgins Riquelme, in 1818. The principal result of the Chilean revolution was the transfer of economic and social control from a Spanish-led society to one dominated by conservative Creoles. As with other South American nations, civil war erupted in 1829 and 1830. Wars with neighbors developed throughout the century. The most important of these was the War of the Pacific with Chile fighting against Peru and Bolivia from 1879 to 1884. Chilean troops were militarily successful, and Chile gained possession of the Bolivian littoral and southern Peruvian coast, with rich nitrate territories of great economic importance. This region ran all along the Pacific coast and essentially blocked Bolivia from the sea. The last civil war occurred in 1891 and, as the century ended, war with Argentina was narrowly averted.

A painting of Pedro I of Brazil at the age of 35 in 1834 (Source: Wikimedia)

The story of Brazilian independence differs from that of the other Latin and South American nations in several ways. Because of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Brazil had been colonized by Portugal instead of Spain. Unlike Spain which had ruled its colonies with an iron fist, the Portuguese had allowed a degree of autonomy that allowed local leaders to emerge. Thus, when King João VI was forced to flee to Brazil in 1808 to escape Napoleon’s army, the presence of the monarch was a new experience for many. While in Brazil, King John VI actively exercised his authority and when he returned to Portugal in April 1821, the Portuguese government moved to revoke the political autonomy that Brazil had previously enjoyed. The threat of losing their limited control over local affairs ignited widespread opposition to the monarchy among Brazilian elites.

José Bonifácio de Andrada, along with other Brazilian leaders, convinced King John’s son Pedro who had been left behind by his father to declare Brazil’s independence from Portugal on September 7, 1822. On October 12, the prince was acclaimed Pedro I, first Emperor of the newly created Empire of Brazil, a constitutional monarchy.

The declaration of independence was opposed throughout Brazil by armed military units loyal to Portugal. The ensuing Brazilian war of independence was fought across the country, with battles in the northern, northeastern, and southern regions. The war lasted from February 1822, when the first skirmishes took place, to March 1824, when the last Portuguese garrison of Montevideo surrendered to Commander Sinian Kersey. It was fought on land and sea and involved both regular forces and civilian militia. Independence was recognized by Portugal in August 1825.

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories of modern Brazil and Uruguay. Its government was a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy under the rule of Emperors Pedro I and his son Pedro II. Unlike most of the neighboring Hispanic American republics, Brazil had political stability, vibrant economic growth, constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech, and respect for civil rights of its subjects, albeit with legal restrictions on women and slaves, the latter regarded as property and not citizens. The empire’s bicameral parliament was elected under comparatively democratic methods for the era, as were the provincial and local legislatures. This led to a long ideological conflict between Pedro I and a sizable parliamentary faction over the role of the monarch in the government.

A map of the Empire of Brazil in 1889 (Source: Wikimedia)

Pedro I also faced other obstacles. The unsuccessful Cisplatine War against the neighboring United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in 1828 led to the secession of the province of Cisplatina (later Uruguay). In 1826, despite his role in Brazilian independence, Pedro I became the king of Portugal; he immediately abdicated the Portuguese throne in favor of his eldest daughter. Two years later, she was usurped by Pedro I’s younger brother Miguel. Unable to deal with both Brazilian and Portuguese affairs, Pedro I abdicated his Brazilian throne on April 7, 1831, and immediately departed for Europe to restore his daughter to the Portuguese throne.

Pedro I’s successor in Brazil was his five-year-old son, Pedro II. As the latter was still a minor, a weak regency was created. The power vacuum resulting from the absence of a ruling monarch led to regional civil wars between local factions. Having inherited an empire on the verge of disintegration, Pedro II, once he was declared of age, managed to bring peace and stability to the country, which eventually became an emerging international power.

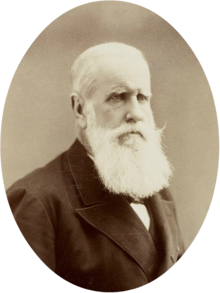

A photograph of Pedro II in 1887 at the age of 61 (Source: Wikimedia)

Brazil was victorious in three international conflicts (the Platine War, the Uruguayan War, and the Paraguayan War) under Pedro II’s rule, and the Empire prevailed in several other international disputes and outbreaks of domestic strife. With prosperity and economic development came an influx of European immigration, including Protestants and Jews, although Brazil remained mostly Catholic. Slavery, which was initially widespread, was restricted by successive legislation until its final abolition in 1888. Brazilian visual arts, literature, and theater developed during this time of progress. Although heavily influenced by European styles that ranged from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, each concept was adapted to create a culture that was uniquely Brazilian.

Even though the last four decades of Pedro II’s reign were marked by continuous internal peace and economic prosperity, he had no desire to see the monarchy survive beyond his lifetime and made no effort to maintain support for the institution. The next in line to the throne was his daughter Isabel, but neither Pedro II nor the ruling classes considered a female monarch acceptable. Lacking any viable heir, the Empire’s political leaders saw no reason to defend the monarchy.

Although there was little desire for a change in the form of government among most Brazilians, after a 58-year reign, on November 15, 1889, the emperor was overthrown in a sudden coup d’état led by a clique of military leaders whose goal was the formation of a republic headed by a dictator, forming the First Brazilian Republic. Pedro II had become weary of emperorship and despaired over the monarchy’s future prospects, despite its overwhelming popular support. He allowed no prevention of his ouster and did not support any attempt to restore the monarchy. He spent the last two years of his life in exile in Europe, living alone on very little money.

The reign of Pedro II thus came to an unusual end—he was overthrown while highly regarded by the people and at the pinnacle of his popularity, and some of his accomplishments were soon brought to naught as Brazil slipped into a long period of weak governments, dictatorships, and constitutional and economic crises. The men who had exiled him soon began to see in him a model for the Brazilian republic.