52 POST-COLONIAL AFRICA

Even as the United States and the Soviet Union struggled for power and influence in the Cold War, much of the world was engaged in a different kind of contest. This was especially true in Africa, where peoples who have been controlled by Europeans for over a century worked to realize the dream of independence. In 1900, Africa was under the domination of European powers; by the end of the 20th century, African nation-states had triumphed in their struggle for freedom. The first stage of decolonization began in Asia and the Middle East in the late 1940s as the Philippines, India, Pakistan, Myanmar (Burma), Indonesia, Syria, Iraq, and Jordan achieved independence. The decades from the 1950s to the 1970s were the age of African freedom as more than 50 nations threw off the yoke of European dominance and earned their freedom.

As these newly emerging nations struggled to establish themselves, imperialism cast a long shadow over Africa. Divisions within African societies had been exploited by Europeans as they utilized a “divide and conquer” approach to governing. The anger and resentment caused by this exploitation erupted in many places after independence. The presence of many Europeans who had immigrated to Africa in the early 19th century and who considered themselves to be “white Africans” also raised significant political questions that many found difficult to answer. Since many of these “white Africans” owned both land and industries questions of economic justice were also at the forefront in the aftermath of World War II.

Thus, the movement towards independence by African countries was uneven. In places like the Belgian Congo, independence was achieved within a few years. In other places, like Egypt, the struggle lasted for decades. In many places, like French West Africa, the freedom movement relied on peaceful political pressure – demonstrations, strikes, mass mobilization, and negotiations – to achieve independence. But in other areas, such as French Algeria, armed resistance was required. Finally, the struggle in South Africa was unique in that was not waged against a foreign power but against a white minority representing less than 20% of the population who had systematically oppressed non-whites in the racially repressive system known as Apartheid.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

For an overview of the process of decolonization in Asia and Africa, watch Crash Course in World History, #40. |

French West Africa

As the French pursued their part in the “scramble for Africa” in the 1880s and 1890s, they conquered large inland areas in north-west Africa. These conquered areas were usually governed by French Army officers and dubbed “Military Territories.” The French colonial empire began to disintegrate during the Second World War, when various parts were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the USA and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia).

This map shows French West Africa in green. French Algeria is shown in black and other French territories are represented in grey. (Source: Wikimedia)

By the close of the Second World War, the colonized peoples of French West Africa were expressing their dissatisfaction with the colonial system. West Africans had participated in both World Wars to varying degrees and their experiences in them, along with a growing opposition to direct rule and its exploitative nature, resulted in a movement which would ultimately lead to independence for the territories. In response to this growing demand, the French government began extending limited political rights in its colonies. Reforms which included African representation in the French National Assembly and the increase of local councils in West Africa where Africans could participate in local governance were proposed and slowly accepted by the French. The rise of political parties and nationalist programs in French West Africa grew steadily. Parties such as Felix Houphouet-Boigny’s RDA in the Ivory Coast (Rassemblement Democratique Africain) and Leopold Senghor’s Convention Africaine in Senegal gained support. In 1956, the French passed the “enabling law,” which allowed local government for individual territories in French West Africa. By 1960, all of the territories of French West Africa had achieved independence.

Leopold Senghor, shown in this photograph, was the first elected President of Senegal (Source: Wikipedia)

The Algerian War of Independence

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian War of Independence or the Algerian Revolution, was a war between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front from 1954 to 1962 and led to Algerian independence from France. An important decolonization war, this complex conflict was characterized by guerrilla warfare and the use of torture by both sides.

By the end of the 1950s, the lack of French support for the war and the pressure of international outrage at the human rights abuses committed by the French convinced President Charles De Gaulle to negotiate with the National Liberation Front. On February 20, 1962, a peace accord was reached for granting independence to all of Algeria. The Évian Accords which officially ended the War were signed on March 1962. These Accords also codified the process of independence for Algeria. De Gaulle formally pronounced Algeria an independent country on July 3, 1962.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch a 1956 newsreel that discusses the War in Algeria from a decidedly pro-French perspective.

|

Moroccan Independence

As Europe industrialized in the 19th century, North Africa was increasingly prized for its potential for colonization. France showed a strong interest in Morocco as early as 1830, not only to protect the border of its Algerian territory but also because of the strategic position of Morocco on two oceans. In 1860, a dispute over Spain’s Ceuta enclave led Spain to declare war. Victorious Spain won a further enclave and an enlarged Ceuta in the settlement. In 1884, Spain created a protectorate in the coastal areas of Morocco. The 1912 Treaty of Fez made Morocco a protectorate of France. After the Treaty, tens of thousands of French colonists entered Morocco. Some bought large amounts of rich agricultural land, while others organized the exploitation and modernization of mines and harbors.

During World War II, Moroccans began to hope for political change in the post-war era. In January 1944, the Istiqlal Party, which subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement, released a manifesto demanding full independence, national reunification, and a democratic constitution. The French authority in Morocco adamantly refused to even consider independence. Official intransigence contributed to increased animosity between the nationalists and the colonists. The most notable violence occurred in Oujda where Moroccans attacked French and other European residents in the streets. Believing Sultan Mohammed V (the son of Sultan Yusef) to be responsible, France removed him from power and replaced him with Mohammed Ben Aarafa who proved to be extremely unpopular. The actions of the French increased opposition to the French protectorate both from nationalists and those who saw the sultan as a religious leader. Two years later, faced with a united Moroccan demand for the sultan’s return and rising violence in Morocco, as well as a deteriorating situation in Algeria, the French government brought Mohammed V back to Morocco, and the following year began the negotiations that led to Moroccan independence. In March 1956, the French protectorate was ended, and Morocco regained its independence from France as the “Kingdom of Morocco.” In the months that followed independence, King Mohammed V proceeded to build a modern government structure under a constitutional monarchy. He acted cautiously, with no intention of permitting more radical elements in the nationalist movement to overthrow the established order.

A photograph of Sultan Mohammed V with his family in 1956 (Source: Wikimedia)

Libya

The Italo-Turkish War was fought between the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and the Kingdom of Italy from September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet province and turned it into a colony. From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, approximately 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.

This map shows the location of Libya in green (Source: Wikimedia)

In June 1940, after Italy entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers, Libya became the setting for the hard-fought North African Campaign that ultimately ended in defeat for Italy and its German ally in 1943. From 1943 to 1951, Libya was under Allied occupation. The British military administered the two former Italian Libyan provinces of Tripolitana and Cyrenaïca, while the French administered the province of Fezzan. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya. On November 21, 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris, Libya’s only monarch.

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world’s poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government’s finances, resentment among some factions began to build over the increased concentration of the nation’s wealth in the hands of King Idris. On September 1, 1969, a small group of military officers led by 27-year-old army officer Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris, launching the Libyan Revolution. Gaddafi was referred to as the “Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution” in government statements and the official Libyan press. On the birthday of Muhammad in 1973, Gaddafi delivered a “Five-Point Address.” He announced the suspension of all existing laws and the implementation of Sharia. He said that the country would be purged of the “politically sick.” A “people’s militia” would “protect the revolution.” There would be an administrative revolution and a cultural revolution. Gaddafi set up an extensive surveillance system: 10 to 20 percent of Libyans worked in surveillance for the Revolutionary committees, which monitored place in government, factories, and the education sector. Gaddafi executed dissidents publicly and the executions were often rebroadcast on state television channels. He employed his network of diplomats and recruits to assassinate dozens of critical refugees around the world. Gaddafi was ruler of Libya until the 2011 Libyan Civil War, when he was deposed with the backing of NATO. Since then, Libya has experienced instability.

A photograph of Muammar Gaddafi in the 1970s (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the struggle for independence in Libya and the unique post-independence history of this nation by reading “The Muammar Gaddafi Story.”

|

Egypt

Egypt was controlled by Great Britain through the early decades of the 20th century. On September 23, 1945, after the end of World War II, Egyptians demanded an end to British military presence and political control. Great Britain agreed to withdraw its troops in the Anglo–Egyptian Agreement of 1954. The British withdrawal was completed in June 1956. This is the date when Egypt gained full independence.

Wholesale agrarian reform and huge industrialization programs were initiated in the first 15 years of the newly formed independent Egypt, leading to an unprecedented period of infrastructure building and urbanization. The early successes of the independence movement in Egypt encouraged numerous other nationalist movements in other Arab and African countries, such as Algeria and Kenya, where there were anti-colonial rebellions against European empires. It also inspired the toppling of existing pro-Western monarchies and governments in the region and continent.

General Gamal Abdel Nasser ruled Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. He was followed by President Anwar Sadat. Sadat’s presidency saw many changes in Egypt’s direction, reversing some of the economic and political principles of Nasserism by breaking with Soviet Union to make Egypt an ally of the United States, initiating the peace process with Israel, reinstituting the multi-party system, and abandoning socialism by launching the Infitah economic policy.

Nasser is cheered by crowds after announcing the withdrawal of British troops in 1954 (Source: Wikimedia)

In foreign relations Sadat instigated momentous change, shifting Egypt from a policy of confrontation with Israel to one of peaceful accommodation through negotiations. Following the Sinai Disengagement Agreements of 1974 and 1975, Sadat created a fresh opening for progress by his dramatic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977. This led to an invitation from President Jimmy Carter of the United States to President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin to enter trilateral negotiations at Camp David. The outcome was the historic Camp David accords, signed by Egypt and Israel and witnessed by the U.S. on September 17, 1978. The accords led to the March 26, 1979, signing of the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty, by which Egypt regained control of the Sinai in May 1982. Throughout this period, U.S.–Egyptian relations steadily improved, and Egypt became one of America’s largest recipients of foreign aid. Sadat’s willingness to break ranks by making peace with Israel earned him the enmity of most other Arab states, however.

Sadat’s liberalization also included the reinstitution of due process and the legal banning of torture. He dismantled much of the existing political machine and brought to trial a number of former government officials accused of criminal excesses during the Nasser era. Sadat tried to expand participation in the political process in the mid-1970s. In the last years of his life, Egypt was wracked by violence arising from discontent with Sadat’s rule and sectarian tensions and experienced a renewed measure of repression including extra judicial arrests.

A photograph shows President Jimmy Carter with Sadat (to his left) and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin after the signing of the Camp David Accords (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch a newsreel from 1972 discussing the changes brought to Egypt by President Anwar Sadat.

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo / Zaire

An African nationalist movement developed that aimed to liberate the Congo from Belgian rule during the 1950s among the urbanized elite of the country. Major riots broke out in Léopoldville, the Congolese capital, on January 4, 1959, after a political demonstration turned violent. The colonial army, the Force Publique, used force against the rioters—at least 49 people were killed, and total casualties may have been as high as 500. As the news of the attack circulated, the nationalist movement expanded outside the major cities for the first time. Nationalist demonstrations and riots became a regular occurrence over the next year, bringing large numbers of black people from outside the elite class into the independence movement. Many black Africans began to test the boundaries of the colonial system by refusing to pay taxes or abide by minor colonial regulations.

This map shows the location of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in dark green (Source: Wikimedia)

The proclamation of the independent Republic of the Congo and the end of colonial rule occurred on June 30, 1960. Disputes between the leaders of the nationalist movement reputed. A violent struggle resulted in the ascension of Joseph-Desire Mobutu to sole power. Under the auspices of a regime d’exception (the equivalent of a state of emergency), Mobutu assumed sweeping—almost absolute—powers for five years. In his first speech upon taking power, Mobutu told a large crowd at Léopoldville’s main stadium that since politicians had brought the country to ruin in five years, “for five years, there will be no more political party activity in the country.” Parliament was reduced to a rubber-stamp before being abolished altogether. The number of provinces was reduced and their autonomy curtailed, resulting in a highly centralized state. Although relative peace and stability were achieved, Mobutu’s government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality, and corruption. A constitutional referendum after Mobutu’s coup of 1965 resulted in the country’s official name being changed to the “Democratic Republic of the Congo.” In 1971, Mobutu changed the name again, this time to “Republic of Zaire.”

A photograph of Joseph-Desire Mobutu in 1960 (Source: Wikimedia)

Authenticité, sometimes Zairianisation in English, was an official state ideology of the Mobutu regime that originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The authenticity campaign was an effort to rid the country of the lingering vestiges of colonialism and the continuing influence of Western culture and create a more centralized and singular national identity. The policy, as implemented, included numerous changes to the state and to private life, including the renaming of the Congo (to Zaire) and its cities (Leopoldville became Kinshasa, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Stanleyville became Kisangani), as well as an eventual mandate that Zairians were to abandon their Christian names for more “authentic” ones. In addition, Western-style attire was banned and replaced with the Mao-style tunic labeled the “abacost” and its female equivalent.

In 1972, Mobutu renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (“The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake”), Mobutu Sese Seko for short. Mobutu ruled until 1997, when rebel forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila expelled him from the country. Already suffering from advanced prostate cancer, he died three months later in Morocco.

This photograph shows Mobutu wearing an abacost on a trip to Washington D.C. in 1983 (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the struggle for freedom in the Congo and Rwanda by watching Crash Course in World History #221

|

Rhodesia / Zimbabwe

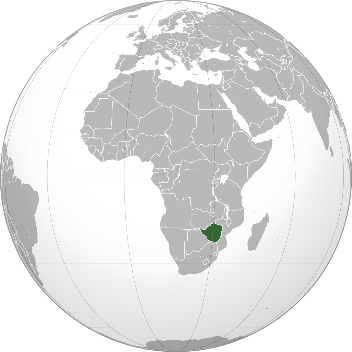

In 1965, the conservative white minority government in Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from Great Britain in a statement called the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI). Most white Rhodesians felt that they were due independence following four decades of self-government. However, because the UDI was issued by a government composed of representatives of the white population of Rhodesia (which was only 5% of the total population), both Britain and the UN opposed it under the political principle of “no independence before majority rule.” Amidst this backdrop, black nationalists advocated armed struggle to bring about independence in Rhodesia under black majority rule. Resistance also stemmed from the wide economic inequality between blacks and whites. In Rhodesia, whites owned most of the fertile land while blacks were crowded on barren land following forced evictions or clearances by the colonial authorities.

This map shows the location of Rhodesia (later renamed Zimbabwe) in green (Source: Wikimedia)

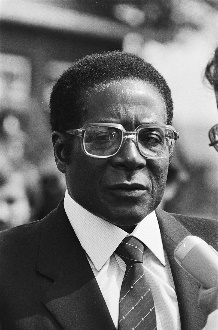

Robert Mugabe rose to prominence in the 1960s as the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) during the war against the conservative white-minority government of Rhodesia. At the end of the sustained conflict in 1979, Mugabe emerged as a hero in the minds of many Africans. He won the general elections of 1980 after calling for reconciliation between the former belligerents, including white Zimbabweans and rival political parties, and thereby became Prime Minister upon Zimbabwe’s independence in April 1980. Soon after independence, Mugabe set about creating a one-party state and establishing a North Korean-trained security force, the Fifth Brigade, in August 1981, to deal with internal dissidents. Between 1982 and 1985, at least 20,000 people died in ethnic cleansing and were buried in mass graves. Mugabe consolidated his power in December 1987, when he was declared executive president by parliament, combining the roles of head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the armed forces with powers to dissolve parliament and declare martial law.

Since 1998, Mugabe’s policies have elicited domestic and international denunciation. Mugabe’s critics accuse him of conducting a “reign of terror” and being an “extremely poor role model” for the continent, saying his “transgressions are unpardonable.” According to human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, the government of Zimbabwe violates the rights to shelter, food, freedom of movement and residence, freedom of assembly, and the protection of the law. There have been alleged assaults on the media, the political opposition, civil society activists, and human rights defenders. By 2000, the living standards in Zimbabwe had declined from 1980. Life expectancy was reduced, average wages were lower, and unemployment had tripled.

A photograph of Robert Mugabe in 1982 (Source: Wikimedia)

South Africa

Much of South Africa’s history, particularly of the colonial and post-colonial eras, is characterized by clashes of culture, violent territorial disputes between European settlers and indigenous people, dispossession and repression, and other racial and political tensions. Following the defeat of the Boers in the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the Union of South Africa was created as a dominion of the British Empire, which unified into one entity the four previously separate British colonies: Cape Colony, Natal Colony, Transvaal Colony, and Orange River Colony.

This map shows the location of provinces of the Union of South Africa (Source: Wikimedia)

During the immediate post-Boer war years, the British focused their attention on rebuilding the country, especially the mining industry. By 1907, the mines of the Witwatersrand produced almost one-third of the world’s annual gold production. But the peace brought by the treaty remained fragile and challenged on all sides. Afrikaners found themselves in the difficult position of poor farmers in a country where big mining ventures and foreign capital rendered them irrelevant. Britain’s unsuccessful attempts to anglicize them and impose English as the official language in schools and the workplace particularly angered them.

Blacks remained marginalized in society. The British High Commissioner Lord Alfred Milner introduced “segregation,” later known as apartheid. The authorities imposed harsh taxes and reduced wages while the British caretaker administrator encouraged the immigration of thousands of Chinese to undercut any resistance. Among other harsh segregationist laws, including denial of voting rights to blacks, the Union parliament enacted the 1913 Natives’ Land Act, which earmarked only eight percent of South Africa’s available land for black occupancy. White people, who constituted 20 percent of the population, held 90 percent of the land. The Land Act formed the cornerstone of legalized racial discrimination for the next nine decades.

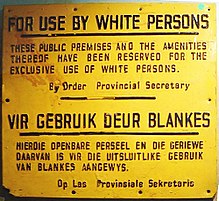

An apartheid sign demonstrating that apartheid legislation impacted all areas of life (Source: Wikimedia)

Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination in South Africa instituted in 1948 that lasted until its repeal in 1991. The first piece of apartheid legislation was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act in 1949, which was followed closely by the Immorality Act of 1950, making it illegal for South African citizens to marry or pursue sexual relationships across racial lines. The Population Registration Act, 1950, classified all South Africans into one of four racial groups based on appearance, known ancestry, socioeconomic status, and cultural lifestyle. NP leaders argued that South Africa did not comprise a single nation but was made up of four distinct racial groups: White, Black, Colored, and Indian. The Colored group included people regarded as of mixed descent, including of Bantu, Khoisan, European, and Malay ancestry. Such groups were split into 13 nations or racial federations. White people encompassed the English and Afrikaans language groups; the black populace was divided into ten such groups.

Places of residence were determined by racial classification under the Group Areas Act of 1950. From 1960 to 1983, 3.5 million nonwhite South Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighborhoods in one of the largest mass removals in modern history. These removals included people relocated due to slum clearance programs, labor tenants on white-owned farms, the inhabitants of the so-called “black spots” (black-owned land surrounded by white farms), the families of workers living in townships close to the homelands, and “surplus people” from urban areas, including thousands of people from the Western Cape.

The NP also passed a string of legislation that became known as petty apartheid. Acts passed under petty apartheid were meant to separate nonwhites from daily life. Blacks were not allowed to run businesses or professional practices in areas designated as “white South Africa” unless they had a permit. Transport and civil facilities were segregated. Black buses stopped at black bus stops and white buses at white ones. Trains, hospitals, and ambulances were segregated. Because there were fewer white patients and white doctors preferred to work in white hospitals, conditions in white hospitals were much better than those in often overcrowded and understaffed black hospitals.

Apartheid sparked significant international and domestic opposition, resulting in some of the most influential global social movements of the twentieth century. It was the target of frequent condemnation in the United Nations and brought about an extensive arms and trade embargo on South Africa. During the 1970s and 1980s, internal resistance to apartheid became increasingly militant, prompting brutal crackdowns by the National Party administration and protracted sectarian violence that left thousands dead or in detention. Some reforms of the apartheid system were undertaken, including allowing for Indian and Colored political representation in parliament, but these measures failed to appease most activist groups.

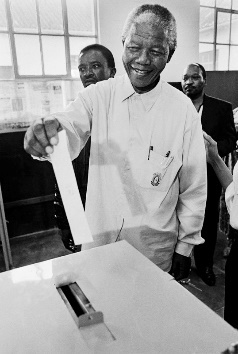

Between 1987 and 1993, the National Party entered into bilateral negotiations with the African National Congress, the leading anti-apartheid political movement, to end segregation and introduce majority rule. In 1990, prominent ANC leaders such as Nelson Mandela were released from detention. Apartheid legislation was abolished in mid-1991, pending multiracial elections set for April 1994. Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black President in 1994.

A photograph of Nelson Mandela voting in South Africa’s first free election in which all South Africans could vote (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the life of Nelson Mandela and his leadership in South Africa by watching the short video: Nelson Mandela: Civil Rights Activist and President of South Africa

|

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

In 1995, Nelson Mandela published his autobiography entitled, Long Walk to Freedom. In the excerpt below, he discusses how he came to love freedom as a political prisoner of the Apartheid Government: It was during those long and lonely years that my hunger for the freedom of my own people became a hunger for the freedom of all people, white and black. I knew as well as I knew anything that the oppressor must be liberated just as surely as the oppressed. A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred, he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. I am not truly free if I am taking away someone else’s freedom, just as surely as I am not free when my freedom is taken from me. The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity. When I walked out of prison, that was my mission, to liberate the oppressed and the oppressor both. Some say that has now been achieved. But I know that that is not the case. The truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. The true test of our devotion to freedom is just beginning. I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can rest only for a moment, for with freedom comes responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended. You can read a longer excerpt of his autobiography here. |

|