14 AFRICA

NORTHEAST AFRICA

In the early 17th century, Ethiopian emperors aimed to reassert their authority and establish a stable royal capital at Gondar after a period of decline and instability. The Ethiopian Empire had faced significant challenges, including internal power struggles, external threats from neighboring Muslim states, and the influence of European missionaries. Emperor Fasilides, who ruled from 1632 to 1667, was instrumental in this resurgence. He expelled the Jesuits, who had been attempting to convert Ethiopians to Catholicism, by 1633 and worked to suppress the Muslim state of Adal. Fasilides also implemented a policy of isolationism, closing the country’s borders to foreigners and limiting external influence. This approach helped preserve Ethiopia’s unique cultural identity and Orthodox Christian heritage.

Despite Emperor Fasilides’ consolidation of power, local conflicts persisted. Wars with neighboring Muslim states and the Galla people, who were farmers in central and southern Ethiopia, continued intermittently. The Galla, who had been migrating into Ethiopian territories, began to intermarry with Arabs and embraced Islam, contributing to the growth of Islamic influence in the region.

Meanwhile, in Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, having conquered the region in 1517, continued to exert its control. The Ottomans’ presence had a profound impact on the political and cultural landscape of North Africa and the Middle East, shaping the course of Islamic history in the region.

NORTH CENTRAL AND NORTHWEST AFRICA

The Maghreb region of North Africa underwent significant transformations in the 17th century. The Ottoman Empire, which had established its presence in the region during the previous century, continued to exert its influence, particularly in Algeria and Tunisia. Local dynasties, such as the Muradid dynasty in Tunisia, founded by Murad Bey in 1613, began to assert their autonomy, leading to a complex web of alliances and rivalries among local rulers, Ottoman authorities, and European powers. This led to a delicate balance of power, with each faction vying for control. In Morocco, the Saadian dynasty faced internal and external pressures, ultimately paving the way for the rise of the Alaouite dynasty towards the end of the century.

The trans-Saharan trade routes remained a vital lifeline for the region, connecting North Africa to West Africa and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. Cities like Timbuktu, Gao, and Kano emerged as important centers of commerce, learning, and cultural exchange, attracting scholars, merchants, and travelers from across the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa. However, the Barbary pirates, operating from ports like Algiers and Salé, posed a significant threat to maritime commerce, disrupting European shipping and trade routes. The shifting power dynamics in Morocco and the ongoing influence of the Ottoman Empire in other parts of the Maghreb shaped the political and economic landscape of the region during this period, creating opportunities and challenges for local populations.

For ordinary people in the Maghreb, the 17th century was marked by hardship and uncertainty. Most lived in rural areas, working as farmers, herders, or artisans, and struggled to make a living from the often harsh and arid environment. Cities like Fez, Marrakech, and Tunis offered more opportunities, but also exposed residents to disease, poverty, and exploitation. Slavery was a harsh reality, particularly along the Barbary Coast, where pirates captured people from sub-Saharan Africa and Europe to be sold into bondage. Despite these challenges, people found comfort and hope in their cultural traditions, engaged in vibrant community life, and maintained strong social bonds, demonstrating remarkable resilience and adaptability in the face of frequent droughts, famines, and political upheavals.

SUBSAHARAN AFRICA

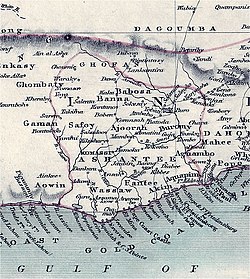

In the 17th century, the Ashanti Kingdom emerged in what is now modern-day Ghana, rapidly expanding to absorb around 30 independent neighboring kingdoms. The Ashanti people were skilled traders who leveraged their strategic location to establish lucrative trade relationships with European powers, particularly in the African slave trade. Under the leadership of powerful rulers like Osei Tutu (c. 1695-1717), who founded the Ashanti Empire, and Opoku Ware I (c. 1720-1750), who expanded its borders and solidified its power, the Ashanti Kingdom became a dominant force in the region, known for its military prowess, administrative efficiency, and rich cultural heritage. The Ashanti’s involvement in the slave trade, however, had devastating consequences for the people of West Africa, as millions were forcibly captured and sold into bondage. Meanwhile, other powerful states like Dahomey and Oyo emerged in the region, earning the entire area the notorious nickname “the Slave Coast.” These kingdoms played significant roles in shaping the complex and often brutal history of the transatlantic slave trade.

A map of the Ashanti Kingdom (Source: Wikimedia)

The trans-Saharan trade routes remained a vital lifeline for the region, connecting North Africa to West Africa and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. Cities like Timbuktu, Gao, and Kano emerged as important centers of commerce, learning, and cultural exchange, attracting scholars, merchants, and travelers from across the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa. However, the Barbary pirates, operating from ports like Algiers and Salé, posed a significant threat to maritime commerce, disrupting European shipping and trade routes. The shifting power dynamics in Morocco and the ongoing influence of the Ottoman Empire in other parts of the Maghreb shaped the political and economic landscape of the region during this period, creating opportunities and challenges for local populations.

For ordinary people in the Maghreb, the 17th century was marked by hardship and uncertainty. Most lived in rural areas, working as farmers, herders, or artisans, and struggled to make a living from the often harsh and arid environment. Cities like Fez, Marrakech, and Tunis offered more opportunities, but also exposed residents to disease, poverty, and exploitation. Slavery was a harsh reality, particularly along the Barbary Coast, where Barbary pirates captured people from sub-Saharan Africa and Europe to be sold into bondage. Despite these challenges, people found comfort and hope in their cultural traditions, engaged in vibrant community life, and maintained strong social bonds, demonstrating remarkable resilience and adaptability in the face of frequent droughts, famines, and political upheavals.

The Kingdom of Kongo’s decline in West Africa was influenced by a combination of environmental degradation, internal strife, and the impact of the transatlantic slave trade. The destabilization contributed to the rise of influential neighboring kingdoms such as the Kuba, Luba, and Lunda. These multi-ethnic states developed advanced political systems and rich cultural traditions. The Kuba Kingdom, located on the southern edge of the rainforest, unified various chiefdoms and achieved a relatively high standard of living, partly due to the introduction of new crops and agricultural techniques from the Americas, brought by the Portuguese.

The Luba kingdom, though geographically more isolated, engaged in regional trade networks and expanded its influence. The Lunda kingdom actively pursued trade, establishing routes to the coast and controlling commerce in goods from the East African coast and the southern interior, extending its reach into the African Copperbelt and toward Lake Tanganyika.

A notable figure of the 17th century was Queen Nzinga of modern-day Angola. After a civil war, she inherited the throne of the Ndongo kingdom in 1624. Nzinga, who had previously negotiated with the Portuguese, initially sought alliances with them but found herself in conflict when Portugal reneged on agreements. Her efforts to resist Portuguese control included seeking support from the Kongo kingdom and Dutch traders. Despite these alliances, Nzinga ultimately signed a peace treaty with Portugal in 1656, bringing an end to hostilities.

One notable event in the 17th century was the rise of Queen Nzinga in modern-day Angola. Following a devastating civil war, Nzinga inherited the throne of the Ndongo kingdom in 1624. She had previously served as an emissary to the Portuguese and negotiated a treaty allowing them to engage in the slave trade within Ndongo territory. However, Portugal reneged on the agreement, leading Nzinga to encourage enslaved people to escape and sparking a war in 1626. Nzinga found allies in the Kongo kingdom and Dutch slave traders, but ultimately concluded a peace treaty with Portugal in 1656, ending hostilities.

The Art of Persuasion: Queen Nzinga’s Diplomatic Triumph

Queen Nzinga’s diplomatic efforts exemplify the power of persuasion in the face of overwhelming odds. When the Portuguese demanded that she surrender her territory and people, Nzinga skillfully negotiated a treaty that allowed her to maintain control while appeasing Portuguese interests. She leveraged her charm, intelligence, and strategic thinking to persuade the Portuguese governor to accept her terms, even going so far as to feign conversion to Christianity to further her goals. Through her persuasive efforts, Nzinga successfully protected her kingdom and people from the ravages of the slave trade, demonstrating the impact that effective communication, empathy, and creative problem-solving can have on achieving desired outcomes, even in the most challenging circumstances. From Queen Nzinga’s example, we can learn that persuasion is not just about achieving a desired outcome, but also about maintaining integrity, dignity, and autonomy in the face of adversity.

Queen Nzinga’s remarkable story embodies several key themes in early modern African history. Firstly, she exemplifies the significant leadership roles African women played in their communities, despite facing challenges to her legitimacy due to her gender. Nzinga demonstrated exceptional military strategy and diplomatic skills in resisting Portuguese threats, ultimately establishing the powerful kingdom of Matamba. By the time of her death in 1663, Matamba had become a major trading power, dealing with the Portuguese on equal terms.

Secondly, Queen Nzinga’s experiences highlight the complex struggles African leaders faced in maintaining their communities’ freedom and dignity in the face of European colonization and the transatlantic slave trade. The European demand for labor drove African involvement in the slave trade, with many states like Matamba participating by providing enslaved people. However, it’s essential to note that African societies had long practiced forms of human servitude, differing significantly from the chattel slavery that developed in the Americas. Traditional African servitude allowed enslaved individuals to possess some rights, work towards freedom, and did not perpetuate slavery to their children.

The transatlantic slave trade, initially dominated by the Portuguese, eventually involved British, Dutch, and French traders, resulting in the forced migration of over ten million enslaved people to the Americas over 450 years. This devastating trade was fueled by the demand for labor on sugar, cotton, and tobacco plantations, forever altering the course of African and world history.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

|

Learn more about African involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade by reading “Willful Amnesia” at the Public Radio International (PRI) website.

|

|

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Not all African peoples participated in the European slave trade. The following letter, written by King Nzinga Mbemba (also known as King Alfonso) of the Kongo Kingdom, to the King of Portugal illustrates the unease many Africans felt about working with Europeans in the enslavement of people: We cannot reckon how great the damage is, since the mentioned merchants are taking every day our natives, sons of the land and the sons of our noblemen and vassals and our relatives, because the thieves and men of bad conscience grab them wishing to have the things and wares of this Kingdom which they are ambitious of; they grab them and get them to be sold; and so great, Sir, is the corruption and licentiousness that our country is being depopulated … Read a longer excerpt of King Nzinga’s letter. |

|

By the end of the 17th century, the Bunyoro Kingdom in present-day Uganda had become one of the most influential powers in East Africa among the Bantu-speaking kingdoms. The Bantu people were known for their craftsmanship, creating intricate wooden sculptures and building palaces, shrines, and houses with great skill. In some Bantu communities, large drums, sometimes as wide as 12 feet, were used in spiritual practices to communicate with ancestors and connect with the spiritual world. These drums were often decorated with symbolic carvings and were considered sacred, used in ceremonies to promote fertility, prosperity, and protection. Additionally, Bantu artisans were known for their colorful textiles, with vibrant patterns featured in their clothing and fabrics.

Meanwhile, in southern Africa, the San people, also known as Bushmen, developed a distinct cultural heritage centered around rock paintings and engravings. The Drakensberg Mountains are home to some of the most impressive examples of San rock art, where animals are depicted in vivid detail. These ancient artworks offer a glimpse into the lives and beliefs of the San people, highlighting their deep connection to nature and their spiritual traditions. The rock art also shows their detailed understanding of animal behavior and migration patterns, reflecting their respect for the land and its creatures. Unfortunately, much of this rock art is at risk due to erosion, vandalism, and neglect, emphasizing the need for efforts to preserve this important cultural heritage.

San rock painting in the Drakensberg Mountains. (Source: Wikimedia