25 AFRICA

NORTHEAST AFRICA

During the 18th century, Northeast Africa underwent significant upheaval and external intervention. In Ethiopia, persistent local conflicts undermined the central government’s authority, allowing various regional groups, including Galla tribesmen, to conduct raids on rural communities. Egypt, a strategically and economically important region, remained under Ottoman control until the late 18th century. However, Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 was a crucial turning point. French forces briefly occupied Egypt with the aim of expanding European influence, disrupting British trade routes, and gaining access to the Middle East and India.

For ordinary people in 18th-century Northeast Africa, life was marked by hardship, uncertainty, and resilience. In rural Ethiopia, farmers and herders struggled to cultivate the land and protect their livestock from raids by Galla tribesmen and other rival groups. In Egyptian villages, peasants worked tirelessly to irrigate and harvest the Nile’s fertile soils, often under the watchful eye of Ottoman tax collectors. Townspeople, meanwhile, navigated crowded markets and narrow streets, seeking livelihoods as artisans, merchants, or traders. Women played vital roles in household management, agriculture, and craft production, but often faced limited social mobility and patriarchal constraints. Amidst these daily challenges, people found solace in traditional practices, such as Islamic Sufism and Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, which provided spiritual comfort and community cohesion. Despite the region’s rich cultural heritage, ordinary people’s lives were shaped by the constant threat of conflict, disease, and environmental hardship.

As the century drew to a close, Northeast Africa faced the convergence of European rivalries, Ottoman decline, and rising colonial ambitions. These dynamics set the stage for significant transformations in the region’s politics, economy, and cultural identity, as new powers began to assert their influence and shape the future of the area.

NORTH CENTRAL AND NORTHWEST AFRICA

In North Central Africa, new dynasties emerged and control shifted during the 18th century. In 1705, Al-Husayn I ibn Ali established the Husainid Dynasty in Tunis, breaking Ottoman dominance and ushering in a period of relative autonomy for the region. Similarly, Ahmed Karamanli took power in Tripoli in 1711 and founded the Karamanli Dynasty, which lasted for over a century. The Karamanlis were known for their diplomatic and military skills, with Yusuf ibn Ali Karamanli, who ruled from 1795 to 1832, being a notable leader. His reign was marked by conflicts with European powers, including the United States. In 1801, the First Barbary War began when the U.S. demanded tribute payments. The war ended in 1805 with a treaty that secured American rights and reduced the tribute payments demanded by the Barbary states, but did not significantly alter the regional power dynamics.

In Northwest Africa, Morocco experienced significant reform and growth under Mohammed ben Abdallah, who ruled from 1757 to 1790. Ben Abdallah implemented a regime of law and order, promoting trade and commerce, and his reign is often considered a golden age in Moroccan history. He also worked to improve Morocco’s internal stability and economic prosperity. However, the region faced external pressures as Spain returned to control Oran in 1732 after having been expelled earlier. Despite these challenges, Morocco retained its independence, with Ben Abdallah skillfully managing the region’s geopolitical complexities to safeguard his country’s sovereignty. His influence continued to shape Moroccan history well beyond his reign.

A Leader’s Vision: Mohammed ben Abdallah’s Mastery of Perspective-Taking

Mohammed ben Abdallah’s success in 18th-century Morocco was significantly enhanced by his exceptional ability to engage in perspective-taking. He demonstrated a remarkable capacity to see things from the point of view of other nations and cultures, understanding their interests, concerns, and motivations. By putting himself in the shoes of European leaders, African kings, and Ottoman sultans, ben Abdallah was able to anticipate their actions and reactions and develop effective strategies to navigate the complex web of alliances and rivalries. This skill allowed him to forge strategic partnerships, avoid conflicts, and secure Morocco’s independence and sovereignty. Through perspective-taking, ben Abdallah was able to build bridges between cultures and nations, ultimately securing his legacy as one of Morocco’s most effective and enlightened leaders.

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

In West Africa during the 18th century, the Ghanaian state was plagued by local conflicts, creating a power vacuum that allowed the Ashanti Empire to rise to dominance. The Ashanti warriors, adorned in opulent regalia featuring locally sourced gold and imported silver, conquered Ghana and established themselves as the supreme power in the interior of sub-Saharan Africa. Under the leadership of their king and major chiefs, the Ashanti Empire flourished, leveraging their control of the gold trade to acquire European firearms and further solidify their position.

The Ashanti Empire, which emerged in the late 17th century, was a powerful and sophisticated state that reached its zenith in the 18th century. Under the leadership of skilled rulers like Osei Tutu and Opoku Ware, the Ashanti expanded their territory through military conquests and strategic alliances, creating a vast empire that stretched from the Ivory Coast to modern-day Ghana. The Ashanti were master craftsmen, renowned for their expertise in goldworking, woodcarving, and textiles, and their capital, Kumasi, became a center of trade and commerce. The empire’s military prowess, administrative efficiency, and cultural achievements solidified its position as a dominant force in West Africa, leaving a lasting legacy in African history and culture.

However, the West African coast remained a hub for the transatlantic slave trade, with the British exploiting their rights, granted by the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), a landmark agreement that ended the War of the Spanish Succession and redistributed colonial territories and trade rights among European powers, allowing them to forcibly enslave millions of Africans. The Ibo people of Guinea were disproportionately affected, with a greater number of slaves coming from this ethnic group than any other. The devastating impact of the slave trade on West African communities was further complicated by the arrival of European powers seeking to establish colonies..

In 1787, the British acquired Sierra Leone, a coastal territory in West Africa, with the intention of resettling freed slaves from the American Revolutionary War. This move marked the beginning of a new era in Sierra Leone’s history, as it was formally established as a separate British colony in 1799. The colony’s founding was motivated by a mix of humanitarian and economic interests, reflecting the complex and often contradictory nature of European involvement in West Africa during this period.

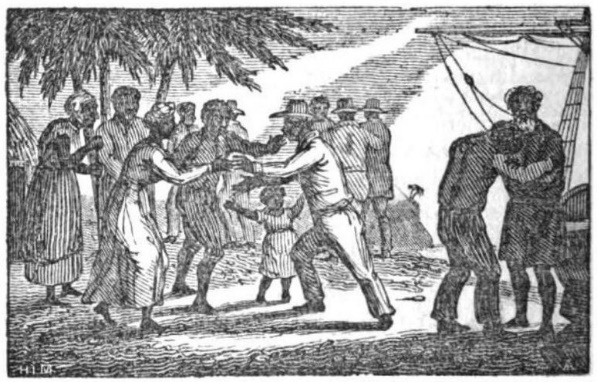

Freed slaves are welcomed to Sierra Leon in this 1835 illustration. (Source: Wikimedia)

In the late 18th century, West African leaders, such as Almamy Abdul Rahman of the Tukulor Empire, expanded their territories and consolidated power. The Tukulor Empire, a prominent force in the region, was known for its military strength and strategic alliances. Merchants built the empire’s prosperity through the active trade networks along the Niger River, which connected West Africa to the Sahara and beyond. Tukulor scholars made notable contributions to Islamic learning, while artisans developed distinctive architectural styles. Women played significant roles in Tukulor society, often serving as advisors and mediators. The empire’s influence extended from the Senegal River to the Niger Delta.

Meanwhile, leaders of the Hausa city-states, located in the region around Lake Chad, continued to assert their power. The Hausa city-states were recognized for their expertise in crafts, agriculture, and commerce. Their strategic position facilitated trade between North Africa, the Sahel, and the forest regions of West Africa. Hausa merchants traded goods such as cotton, leather, and salt, and their scholars developed a rich literary tradition. Women in Hausa society were influential in trade, agriculture, and spiritual leadership. The city-states’ impressive walls and fortifications reflected their engineering skills.

Farther east, the Buganda Kingdom in present-day Uganda developed strong trade relations with Arab and Swahili merchants. The Zande people built a vibrant society in the equatorial region, and Mangbetu craftsmen were known for their advanced metalwork skills. In the southern savannahs, Bakuba artists created detailed portrait statues to honor their king, showcasing their artistic talent. As European explorers and traders began to appear along the African coast, they sought to establish trade relationships and expand their influence. However, African leaders managed to maintain control over their territories, negotiating trade agreements and limiting European dominance.

In the 18th century, Southern Africa experienced significant changes in social, political, and economic dynamics. The rise of the Zulu Kingdom, which began to take shape under the leadership of Shaka Zulu (r. 1816-1828), marked a pivotal moment in the region’s history. Shaka’s leadership was not only characterized by his innovative military strategies, such as the use of the short stabbing spear and the creation of a highly disciplined army, but also by his efforts to consolidate power and unify various groups under a central authority. His administration fostered significant social and political reforms, including the centralization of power and the reorganization of traditional structures. Alongside these developments, European settlers and traders, including the Dutch and later the British, began to establish trade networks and colonial outposts, impacting the region’s economic and social fabric. Indigenous groups such as the Khoikhoi and San faced pressures from these new settler populations and expanding Bantu-speaking communities, leading to shifts in land use and increasing conflicts. These interactions between indigenous communities and Europeans set the stage for profound transformations in Southern Africa’s political and social landscape.

As European colonial ambitions grew, African leaders responded with a combination of resistance and diplomacy. Some, like the Ashanti Empire, formed alliances with European powers to secure trade advantages. Others, like the Tukulor Empire, resisted European encroachment, striving to protect their sovereignty and cultural heritage. Despite these challenges, African societies continued to innovate and thrive, producing remarkable art, literature, and architecture. The legacy of this period still influences African cultures and identities today, highlighting the resilience and creativity of African peoples in the face of colonialism and globalization.