40 EAST AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Unlike other regions of the world, some countries in Asia maintained their independence from direct European control in the 19th century. China, Japan, and Siam (now Thailand) were able to resist aggressive industrialized Western powers and thus avoid outright incorporation into European colonial empires. It was impossible, however, for them to remain isolated as they had in previous centuries. Increasingly, as the 19th century progressed, they became enmeshed in networks of trade that brought them into contact with Europeans. These contacts introduced them to the culture of modernity, with its emphasis on reason and the individual. Each country interacted in its own way with these influences as they engaged in cultural borrowing by adapting them to meet their own cultural traditions and local needs. Engagement with Western ideas impacted young people living in urban areas throughout Asia. They began to think of themselves and their countries in terms borrowed from Europeans even as they merged these ideas with traditional cultural elements. Some began to think of their countries as nations with the inherent right of self-determination and of themselves as citizens with individual rights and responsibilities.

CHINA

Qing China remained the dominate power in East Asia at the beginning of the 19th century. Even though Qing rulers clung tenaciously to their 2000-year-old institutions, it was evident to most that reform was needed. The Qing had squandered both money and prestige in opposing the rebellions of the 18th century. In addition, the two emperors who followed the Qianlong after his death in 1799 proved themselves to be incapable of ruling efficiently. In addition, China was confronted by the increased power and ambitions of Euro-Americans. The English, Dutch, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Americans established colonial empires in Asia in the 19th century. All desired to establish (and control) trade.

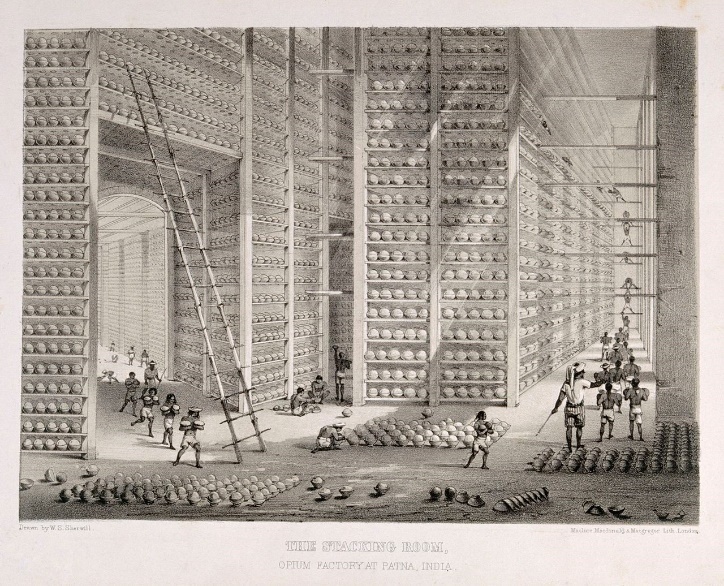

The English were the first to concentrate their colonizing efforts on China. They believed that by forcing the Qing to open their country to trade, a huge new market would be created for the products being produced in English factories. In searching for a product they could use to open the Chinese markets, they focused their efforts on opium. Opium had been developed by Arabs in the 8th century and was originally used as a medicinal remedy for dysentery. In the 19th century, opium was grown and produced in English-controlled India and then exported to China where large numbers of people became addicted. By the early 1830s, the English were selling over 3 million pounds of opium to the Chinese each year.

An artistic depiction of an Opium warehouse in India in 1850 (Source: Wikimedia)

The Chinese authorities, recognizing that opium was injurious to the health of its peoples, declared the opium trade to be illegal. As millions of its people became addicts, the Qing rulers decided to crack down on the illegal trade. Commissioner Lin Zexu led the campaign to eradicate opium from China. He sent his troops to the warehouses in Canton in which opium was stored. When they confiscated and destroyed the opium, the English responded by declaring the Chinese actions to be a violation of their rights. Forty-five naval vessels were sent to the Chinese southern coast where they waged war against the Chinese (called the First Opium War). The results were disastrous for the Qing who were forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842. This treaty (known in China as the first of the unequal treaties) imposed restrictions on Chinese sovereignty and opened five ports for European trade.

This treaty established a pattern that would repeat itself throughout the 19th century. Whenever the Qing tried to assert their right to control trade and to regulate commerce, Europeans threatened military action. A second Opium War was fought from 1856-58 and resulted in further humiliation for the Chinese as the Emperor’s Summer Palace was vandalized by English soldiers. The conclusion of this war resulted in more ports being opened for European traders and the opening of China to Christian missionaries. By the end of the 19th century, the Qing government was forced to allow Europeans to establish “zones of control” in Chinese cities as European nations together with Russia and Japan carved out spheres of influence within the country in which they established military based and from which they extracted natural resources.

An 1898 French political cartoon depicting China as a pie about to be carved up by Queen Victoria (Britain), Kaiser Wilhelm II (Germany), Tsar Nicholas II (Russia), Marianne (France) and a samurai (Japan), while the Chinese helplessly look on. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the Opium Wars by watching this video produced by the Khan Academy.

|

The failure of the Qing in their struggles to oppose European aggression was a major cause of growing domestic discontent. Many Chinese felt that they were second-class citizens in their own country. This was especially frustrating because for two thousand years, China had sustained a highly advanced culture. Regardless of various foreign invader-rulers, the majority of the Chinese lived on the land in self-sufficient villages. Their technology was well advanced with city walls, efficient irrigation systems, and grand palaces. Both rich and poor lived with dignity. However, rapid population growth in the 18th century combined with the inefficient leadership of early 19th century Qing emperors led to periodic food shortages, unemployment, misery, and starvation. By 1850, China’s population had grown from 100 million in 1685 to over 430 million. Corruption and indolence in government made things worse as the suffering of Chinese peasants intensified.

Anti-Qing secret societies became active as gangs of bandits roamed the countryside. The White Lotus Society rebellion, which had started in 1793, seriously disrupted northern China by 1804. This rebellion was a sign of things to come as charismatic leaders emerged to give voice to the grievances of the Chinese people. Increasingly, these leaders championed a message of opposition to the Qing dynasty declaring it to be non-Chinese (because of its Manchu origins).

In 1850, the most serious 19th century rebellion against Qing leadership erupted in southern China known as the Taiping Rebellion. Its leader, Hong Xiuquan (1814-1864), declared himself to be the younger brother of Jesus who had been sent to build the kingdom of God on earth. Calling for a complete reorganization of Chinese society in which private property was abolished and land was redistributed from the wealthy to the poor, Xiuquan’s forces took control of most of China south of the Yangzi and set up their capital in Nanjing. In the fourteen years of the Taiping Rebellion, in the struggle, hundreds of towns were destroyed, and more than 20 million people were killed. However, even though the Qing were able to put down the rebellion and re-establish their authority, rebellions against the dynasty continued. Muslim uprisings which depopulated large areas in Yunnan and an area just south of the Great Wall in the 1860s and 70s. Miao tribal uprisings in Guizhou opposed imperial authority in the 1870s. Violence also erupted in Guangdong resulting in the Punti-Hakka Clan Wars between 1855 and 1867. All in all, these 19th century rebellions were massive destructive resulting in massive casualties and the destruction of much property. They also deeply impacted the Qing dynasty as it found its power and prestige diminished.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

In these excerpts, unknown authors discuss the Taiping economic program. Although these ideas were not implemented, they do illustrate the publicly stated ideals and goals of the movement: The distribution of all land is to be based on the number of persons in each family, regardless of sex. A large family is entitled to more land, a small one to less… All the land in the country is to be cultivated by the whole population together… All people under Heaven are of one family belonging to the Heavenly Father. Nobody shall keep private property. All things should be presented to the Supreme Ruler, so that He will be enabled to make use of them and distribute them equally to all members of his great world-family. Thus all will be sufficiently fed and clothed. You can more excerpts of the Taiping program here. |

|

In the last half of the century, Qing leaders tried to respond to the economic and military incursions of the West with the so-called Self-Strengthening Movement which aimed to adapt western technology without disturbing traditional Chinese political and social order. Led by Li Hongzhang, one of the heroes of the defeat of the Taiping, , this movement emphasized the need to acquire foreign technology in order to defend China. The slogan of the movement, “Western form – Chinese essence,” expressed its plan to adopt western technology while retaining traditional Chinese cultural values. Initial efforts were successful as China updated its military (with special attention to the development of a modern navy), built its first universities, established diplomatic missions in foreign countries, and sent young Chinese men to Europe and the United States to study. In the 1880s, however, reactionary forces in the government regained control and began to shut down the movement’s attempt to modernize China.

A photograph of Sun Yat-sen in 1911 (Source: Wikimedia)

The failure of the Qing dynasty became even more clear in 1894-95, when it fought and lost a war with Japan over influence in Korea. After that humiliating defeat, a generation of revolutionary Chinese leaders, of whom Sun Yat-sen was the most prominent, assumed cultural leadership. In 1898, as a result of their urging, the young Emperor Huang Hsu issued a series of astonishing pro-Western decrees.

In 1898 a Chinese spontaneous, populist movement called the Boxers attempted to have all Europeans expelled from China. Elements in the Chinese government, including the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908), who exercised real power despite the presence of a series of young emperors officially on the throne, supported the Boxer Rebellion. However, the European powers eventually stepped in to end the rising. The peace settlement, which the European powers imposed, declared that the Chinese should pay an enormous sum in reparations to the Europeans. Much later the European powers rescinded their demands for payment, but the entire affair humiliated the Qing government at home and provided another impetus for the forces of change that soon threatened the dynasty.

|

Click and Explore |

|

In 2013, the historical story of the Boxer Rebellion was explored in two graphic novels. Learn more about these novels and the stories they tell by visiting the website, Using Graphic Novels in Education. |

JAPAN

Like China, Japan was forced to abandon isolationism and confront Imperialism in the 19th century. The intrusion began in 1853 when U.S. Commander Matthew Perry’s “black ships” appeared in Tokyo Bay. Although negotiations to open Japan to trade were unsuccessful at that time, when Perry returned eight months later in 1854 with nine ships, many Japanese, well aware of China’s recent defeat in the first Opium War, decided that they had to accept demands for western access to two Japanese ports in agreement, called the Convention of Kanagawa. Four years later, the Harris Treaty of 1858, expanded US rights within Japanese territory. To many Japanese, the capitulation of the aging Tokugawa Shogunate to the demands of the “foreign devils” was a sign that it was no longer capable of leading the nation. An internal power struggle followed. The result was a decisive turning point in modern Japanese history known as the Meijj Restoration.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about Commodore Perry and the opening of Japan by looking at visual images at the MIT Visualizing Cultures online exhibit: Black Ships and Samurai. |

In 1868, a group of young samurai from southern Japan seized the opportunity to force Tokugawa abdication in the name of reinstating direct imperial rule. The young Emperor (only 15-years old) took the name of Meiji which means “enlightened rule.” When the Meiji emperor was restored as head of Japan in 1868, the nation was a militarily weak country, was primarily agricultural, and had little technological development. When the Meiji period ended with the death of the emperor in 1912, Japan was a different country than it was when he came to power. The tone for the reforms was set early in his reign through the proclamation of the Charter Oath (sometimes called the Five-Article Oath). This Oath declared that the new government (in the name of the Emperor) would establish deliberative assemblies so that all members of society (“from the highest to the lowest”) would be involved in decision-making. It also stated the new government’s commitment to “abandon the superstition of the past” by seeking knowledge from “around the world” to strengthen Japan.

The Emperor and his supporters embraced the idea of saving Japan from the imperialistic designs of Euro-Americans. While some originally hoped simply to expel all intruders, they soon adopted the theory was that Japan must grow strong, expand overseas to establish a defense perimeter outside the sacred homeland, and only then expel the barbarians. They committed to an aggressive program of industrialization. The Meiji regime sent influential members of society to Western countries to try to understand their progress and duplicate it. The Iwakarua Embassy, as it became known, traveled both to the United States and Europe to gather knowledge about science, technology, and medicine in order to build a modern Japan that could stand on its own against the imperialistic designs of foreign nations.

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

|

As part of Japan’s outreach the world, the Emperor sent Iwakura Tomomi as an emissary to the United States with the following message for President Ullysses S. Grant: Mr. President: Whereas since our accession by the blessing of heaven to the sacred throne on which our ancestors reigned from time immemorial, we have not dispatched any embassy to the Courts and Governments of friendly countries. We have thought fit to select our trusted and honored minister, Iwakura Tomomi, the Junior Prime Minister (udaijin), as Ambassador Extraordinary … and invested [him] with full powers to proceed to the Government of the United States, as well as to other Governments, in order to declare our cordial friendship, and to place the peaceful relations between our respective nations on a firmer and broader basis. … We expect and intend to reform and improve the same so as to stand upon a similar footing with the most enlightened nations, and to attain the full development of public rights and interest. The civilization and institutions of Japan are so different from those of other countries that we cannot expect to reach the declared end at once. It is our purpose to select from the various institutions prevailing among enlightened nations such as are best suited to our present conditions, and adapt them in gradual reforms and improvements of our policy and customs so as to be upon an equality with them. With this object we desire to fully disclose to the United States Government the constitution of affairs in our Empire, and to consult upon the means of giving greater efficiency to our institutions at present and in the future, and as soon as the said Embassy returns home we will consider the revision of the treaties and accomplish what we have expected and intended.

|

|

Industrialization was a major goal of Japan’s Meiji government, and the state played a greater role in it than in most western countries in the nineteenth century. The Japanese government abolished feudalism and gave peasant farmers title to their land, freeing them to sell it and travel to cities for work in factories and shipyards if they wished. Those who remained on the land were helped to increase Japan’s food production by the government’s importation of fertilizers and farm equipment. The abolition of samurai status freed the warrior elite to use their skills as managers of factories. As the samurai built private wealth, they invested in economic sectors that received less government support. Textile production benefited greatly from this trend, as did brewing and the manufacture of glass and chemicals.

The Japanese improved their armies so that they were able to meet the Western powers on equal terms in battle. They cultivated a strong sense of nationalism and state Shintoism in the populace, believing that a coherent society would be strongest. They continually worked to build a strong, self-sustaining industrial economy. Finally, they overhauled their social and educational institutions to create the most productive possible society of skilled but also community-oriented society. Japan established a public school system in 1872. By 1900, attendance was nearly universal for boys, and girls were not far behind. The new system stressed the study of both science and the Confucian classics.

The goal of the Meiji Restoration was to make sure Japan was capable of competing with larger countries. Japan’s first expansion was north, to the nearby island of Hokkaido. The island was populated by the Ainu, a society of hunter-gatherers. The Japanese sought the land for farming, so they assimilated the Ainu and converted them into farmers. Next, in 1879, Japan annexed the Ryukyu Islands to the south. Tensions between Japan and Korea led the Japanese to invade in 1876. The Japanese annexed territory in some of Korea’s ports and declared that all Korean ports were open for trade with Japan. In the ensuing decades, the Japanese and Chinese battled for influence in Korea. Tensions exploded in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), which the Japanese won. The peace treaty gave the Japanese trading rights in China and forced the Chinese to pay reparations. Japanese influence in China and Korea increased in the early 1900s. The Japanese exacted some control over China’s Fujian Province, across from Taiwan, as well as an indemnity for helping to subdue the Boxer Rebellion. Meanwhile, Japan made Korea a protectorate in 1905 and formally annexed it in 1910. Japan also repelled Russian attempts to curtail its expansion in 1905. Within a short period of time, Japan had grown into a significant empire.

This map shows the full extent of the Japanese Empire in 1942 (Source: Wikimedia)

As Japan’s empire expanded rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not all Japanese citizens supported their country’s imperial ambitions. Some began to question the moral, social, and economic implications of their nation’s aggressive expansion. One notable critic was Kotoku Shusui (1871–1911), a pioneering Japanese socialist and anarchist. Initially, Kotoku supported Japan’s modernization efforts, which were seen as a path to strengthen the nation. However, as Japan’s foreign policy grew increasingly militaristic—leading to conflicts like the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905)—he became disillusioned. Kotoku argued that Japan’s expansionist policies served the interests of the wealthy elite, who profited from colonization and military conquests, while the working class suffered under exploitation and repression. He also warned that Japan’s growing empire threatened to erode democratic values and limit political freedoms.

Kotoku’s growing radicalism eventually led him to advocate for direct action against the Meiji government. His anti-imperial stance and calls for social revolution put him at odds with the authorities, who saw his ideas as a threat to Japan’s stability. He was particularly outspoken in his opposition to Japan’s imperial ventures in Korea and Manchuria, where the exploitation of resources and labor became central to Japan’s empire-building. In 1910, Kotoku was implicated in the High Treason Incident, a plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji. Though there was little evidence connecting him directly to the conspiracy, the government used the incident as an opportunity to silence dissent. Kotoku was convicted and executed by hanging in 1911, marking the end of one of Japan’s most vocal critics of imperialism. His execution became a symbol of the government’s suppression of left-wing ideologies during the Meiji era.

KOREA

Throughout most of the 19th century, traditionalist Korea, like late traditionalist Qing China, clung as much as possible to conservative ways and tried to isolate itself from outside pressures. Until the last 19th century, Korea’s contact with the wider world was limited and it was known in the West as the “Hermit Kingdom.” Koreans were not allowed to travel abroad. The size of boats was restricted so that none were large enough to travel to another country. Foreigners were strictly forbidden from visiting. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, isolation was no longer possible as Korea increasingly was drawn into the complex politics of modern imperialism. It found itself caught in the middle of a dispute between three empires: the declining Chinese, the expanding Russians, and the rising Japanese. Each sought to gain control of Korea. China wanted to maintain its traditional relationship with Korea by making it subordinate to Beijing. Russia, which was expanding its Asian footprint in the 19th century, was interested in its resources and warm water ports. Japan desired to open Korea to trade and thus to create a lucrative market for its manufactured goods.

A dispute between China and Japan over the right to control the Korean peninsula led to war in 1894. When King Kojong asked the Russians for help, a Russian-Korean Bank was formed, and timber and mining concessions were given to Russia. On June 9, 1896, Japan and Russia agreed to the Labanov-Yamagata Agreement under which the two countries jointly oversaw the military and economic affairs of Korea. Tensions between the two countries remained, however, setting the stage for the Russian-Japanese War in the early 20th century. When Japan emerged as victorious in this War in 1905, Korea was declared to be a protectorate of the Japanese. When its appeals for help to the United States and Europe were rejected, Korea found increasingly controlled by the Japanese. In 1910, it was officially annexed by the Japanese.

MYANMAR (BURMA)

Myanmar (also called Burma) having failed to invade Thailand (referred to as Siam in the 19th century) in the 18th century, turned its expansion policy toward the west and seized Manipur and Assam in northeastern India in 1822. This action brought the Myanmar King Bagyidaw into conflict with Great Britain who had established control over the Indian peninsula in the 18th century. Over the course of the next 62 years, there were three Wars with the British. The British won the first war of 1824-26 and seized the southern half of the kingdom. After the 2nd war in 1852, the British occupied the center of the kingdom. After the 3rd war in 1886, Britain completed its conquest and annexed the whole of Myanmar. Great Britain removed the King and established direct control over the nation’s economic and political affairs. The British put great emphasis on expanding agriculture in the Burmese delta. Workers from India and China were imported and the land was devoted to growing rice. By 1910, Myanmar had become the world’s largest exporter of rice.

THAILAND (SIAM) AND CAMBODIA

After the long conflict with Myanmar ended, Thailand secured part of Cambodia through a division of that state with Annam. In 1844, the whole of Cambodia passed under the protection of Thailand’s King Rama IV (1851-1868). Rama was a true polymath — a gifted leader, philosopher, and scientist who taught himself both English and Latin. He befriended Westerners who visited Thailand, read English newspapers, and made a thorough study of western governments. Unlike others throughout Asia who had resisted Western demands to open their societies, King Rama IV cooperated with both the French and the English by opening his kingdom to trade and permitting representatives of their governments to take up residence in his capital city of Bangkok. His astute insight into western politics had led him to conclude that by allowing both nations to have access to his kingdom, neither nation would permit the other to establish exclusive dominance and control.

This map shows the gradual progression of British and French imperialism in Southeast Asia in the 19th century. The flags show which European nation assumed control. (Source: Wikimedia)

Rama also understood that it was necessary for Thailand to appear “modern” to both the British and the French. He initiated reforms that were continued by his son, King Rama V Chulalongkorn (1868-1910). Under their leadership, the old feudal system was abolished, slavery was reduced, and there was administrative reform with new taxation and finance methods. European advisors were invited to help guide the reforms. In 1897 Rama V, who is known today as the Father of modern Thailand, paid an extended visit to the European capitals. Thus, through the remarkable leadership of Rama IV and Rama V, Thailand was the only country in Southeast Asia to resist European control and to remain independent in the 19th century.

VIETNAM (FRENCH INDOCHINA)

At the beginning of the 19th century, most of present-day Vietnam and Laos, at one time all together called French Indochina, was ruled by the Emperor of Annan and the region was predominantly Chinese in culture, with the empire acknowledging the authority of the Chinese emperor. After a long period of dynastic struggles, the three regions of Vietnam (Cochichina, Annan, Tonkin) were united by Nguyen Anh, who took the name Gia Long (1802-1820) when he established the Nyugen dynasty in 1802. Because Emperor Long had received the aid of the French missionary, Perre Pigneau de Behaine, French Catholics were allowed to actively work in Vietnam. It is estimated that by the time of Emperor Long’s death in 1820, more than three hundred thousand Vietnamese had converted to Catholicism.

In 1820, however, series of anti-Christian emperors came to power who resisted the Catholic attempts to convert the Vietnamese. In 1858, the emperor ordered all French missionaries to leave. In response, Napoleon III instructed the French to protect the missions and their Vietnamese converts. His actions forced the emperor to grant France control over the three southern provinces in which the Christians primarily lived. When the Vietnamese ruler proved unwilling to abide by the terms, troops returned in 1862, forcing him to concede yet more territory. By 1887, France had established protectorates over the remaining provinces of Vietnam and over Cambodia. Laos became part of French Indochina after a brief military conflict between Thailand (Siam) and France in 1893.

MALAYSIA

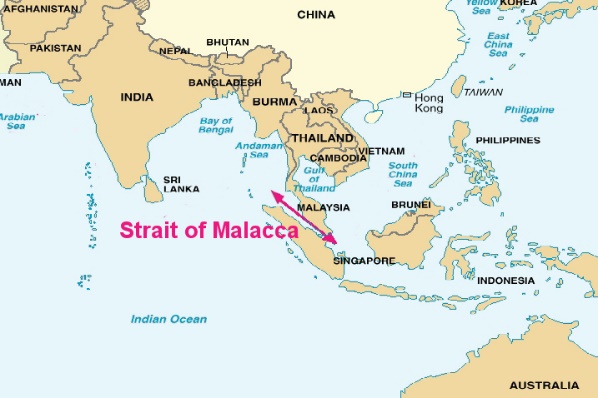

When Holland fell to French revolutionary troops in Europe, the British usurped Malacca and various southeastern Asian islands from the Dutch. British Lt. Governor Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles founded Singapore in 1819, and it was soon to become a strategic and commercial center of the region. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 drew a line through the straits of Malacca, with the English holding Singapore and Malacca, but giving up the Sumatra islands to the Dutch. There was a steady influx of Chinese laborers into the peninsula after 1850, with many working in the tin mines. By 1900, British Malaysia furnished nearly half the world’s supply. The rule of the British East India Company ended in 1867 and thereafter the Malayan Straits settlements had the status of a crown colony directly under the control of the British sovereign. Rubber was first grown there experimentally in 1894.

This map shows the Strait of Malacca in Southeast Asia (Source: Wikimedia)

INDONESIA AND ADJACENT ISLANDS

The British took Java from the Dutch in 1811, although it was restored to the Dutch by the terms of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. In 1825, the Javanese fought for independence from Dutch control under the leader, Diponagora. The war lasted for five years until the Dutch were able to exert control. Flush with their victory, the Dutch proceeded to push into the interior, forcing a new culture system, which involved government contracts, crop control, and fixed prices, on indigenous peoples. Cinchona plantations were established in Java in 1854, giving Europeans the first reliable source of the right kind of bark to supply quinine to protect them against malaria in their world-wide expansion. In 1886, the Dutch even sent medical teams to the Indonesian colonies to study the disease beriberi and they discovered the essence of the vitamin requirements, although the details were not actually clarified until after the turn of the century.

A map shows the location of Java in Southeast Asia (Source: Wikimedia)

The Philippines continued under Spanish control through most of the century, with the Spanish having great difficulty subjugating the freedom-loving Moro people. Although the growing of tobacco, sugar, and hemp had been promoted, Manila was not officially opened to foreign traders until 1834. Jesuit priests gained much power and property. In opposition to the abuses of the Catholic clergy, much sentiment arose for independence under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo. When the Spanish-American war broke out, the Americans took Manila while Aguinaldo led an insurrection against the Spanish. At the war’s end, to the Philippine leader’s great disappointment, the islands were claimed by the United States instead of being granted the right of self-government. Aguinaldo then led another freedom campaign against the United States in 1899. Forced to fight a guerilla war, the Filipinos waged a war for independence until they were subdued in 1902.