53 COMMUNIST CHINA

The history of China in the 20th century begins with the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. It was replaced by the Republic of China that existed from 1912 to 1949. It largely occupied the present-day territories of China, Taiwan, and, for some of its history, Mongolia. World War II effectively ended the Republic as China was plunged into Civil War. The result of this Civil War, which pitted Communists against Nationalists was the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the struggle between the Communists and Nationalists in China by watching Crash Course in World History #37 |

China in WWII

World War II began in Asia before it occurred in Europe, as Japan flexed its military might throughout the region. In 1931, Japan seized control of Manchuria (renaming it Manchukuo). Although this action was condemned by the Chinese, the United States, and the League of Nations, Japan refused to relinquish its hold. In 1937, Japan invaded China from the North, thus initiating a bitter conflict that would last eight years. China fought Japan with aid from the Soviet Union and the United States. This war between Japan and China, known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, was the largest Asian war in the 20th century. It accounted for the majority of civilian and military casualties in the Pacific War, with between ten and twenty-five million Chinese civilians and over four million Chinese and Japanese military personnel dying from war-related violence, famine, and other causes.

In the early years of the conflict, the Japanese scored major victories, capturing Beijing, Shanghai and the Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937, which resulted in the Nanjing Massacre (frequently called the “Rape of Naking”). After failing to stop the Japanese in the Battle of Wuhan, the Chinese Nationalist’s central government was relocated to Chongqing (Chungking) in the far west Chinese interior. By 1939, after Chinese victories in Changsha and Guangxi, and with Japan’s lines of communications stretched deep into the Chinese interior, the war reached a stalemate. The Japanese were unable to defeat the Chinese Communist forces in Shaanxi, which waged a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare against the invaders. While Japan ruled the large cities, they lacked sufficient manpower to control China’s vast countryside.

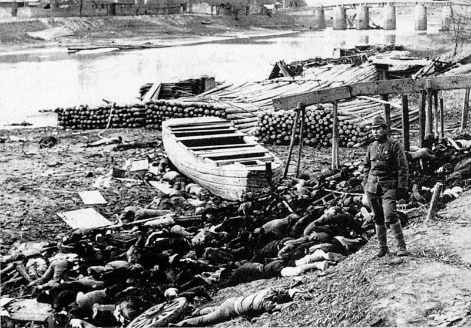

A photograph showing bodies of victims along Qinhuai River out of Nanjing’s west gate during the Nanjing Massacre (Source: Wikimedia)

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

The atrocities committed by the Japanese in Nanjing (also called Nanking) in 1937 are detailed in the following excerpt from the journal of John Rabe, a German businessman who lived in Nanjing at the time of the Japanese invasion: All the shelling and bombing we have thus far experienced are nothing in comparison to the terror that we are going through now: There is not a single shop outside our Zone that has not been looted, and now pillaging, rape, murder, and mayhem are occurring inside the Zone as well. There is not a vacant house, whether with or without a foreign flag, that has not been broken into and looted… No Chinese even dares set foot outside his house! When the gates to my garden are opened to let my car leave the ground… women and children on the street outside kneel and bang their heads against the ground, pleading to be allowed to camp on my garden grounds. You simply cannot conceive of the misery. I’ve just heard that hundreds more disarmed Chinese soldiers have been led out of our Zone to be shot, including 50 of our police who are to be executed for letting soldiers in. The road to Hsiakwan is nothing but a field of corpses strewn with the remains of military equipment… We Europeans are all paralyzed with horror. There are executions everywhere, some are being carried out with machine guns outside the barracks of the War Ministry. You can more excerpts from his diary here. |

|

On August 15, 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Soviet Union invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria, Japan capitulated to Allied forces. Japan continued to occupy part of China’s territory until it formally surrendered on September 2, 1945. The remaining Japanese occupation forces (excluding Manchuria) formally surrendered on September 9, 1945.

At the Cairo Conference of November 22–26, 1943, the Allies of World War II decided to restore all the Chinese territories that Japan annexed, including Manchuria, Taiwan (also known as Formosa), and the Pescadores Islands, to China, and to expel Japan from the Korean Peninsula. China was recognized as one of the Big Four of the Allies during the war and became one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Thus, China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but economically weak and on the verge of all-out civil war between military forces who supported the Nationalists and those who supported the Communists. The economy was sapped by the military demands of a long costly war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by corruption in the Republican government (which has led by the Nationalists) that included profiteering, speculation, and hoarding.

The problems of rehabilitation and reconstruction after the ravages of a protracted war were staggering, and the Republican government proved incapable of meeting the challenges. Their policies also left them unpopular with the majority of the Chinese. Meanwhile, the war had strengthened the Communists both in popularity and as a viable fighting force. Following increased Japanese intrusion into China, popular opinion had forced the Nationalists to enter into a second United Front with the Communists as of December 1936. At Yan’an and elsewhere in the communist controlled areas, Mao Zedong had emerged as the leader of the Communist forces. Mao had adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions. He taught party cadres to lead the masses by living and working with them, eating their food, and thinking their thoughts. Throughout the war, the communist forces (known as the Chinese Red Army) had fostered an image of conducting guerrilla warfare in defense of the people. Communist troops adapted to changing wartime conditions and became a seasoned fighting force. With skillful organization and propaganda, the Communists increased party membership from 100,000 in 1937 to 1.2 million by 1945.

After the War, Mao began to execute his plan to establish a new Communist China by rapidly moving his forces from Yan’an and elsewhere to Manchuria. When the Nationalists moved to oppose him, a violent Civil War broke out between the Nationalists and Communists. During the war, both the Nationalists and the Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants deliberately killed by both sides. Atrocities included deaths from forced conscription and massacres. After three years of exhausting military campaigns, on October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with its capital in Beijing. Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million Nationalist Chinese retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan. In December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan, the temporary capital of the Republic of China and continued to assert his government as the sole legitimate authority in China.

Chairman Mao and the People’s Republic

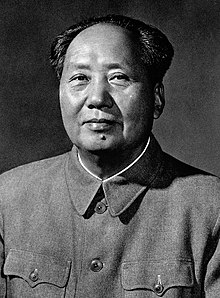

Mao Zedong, known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who became the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, which he ruled as an autocrat Chairman of the Communist Party of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976. His Marxist-Leninist theories, military strategies, and political policies are collectively known as Maoism.

Mao’s revolution that founded the People’s Republic of China was nominally based on Marxism-Leninism with a rural focus (based on China’s social situations at the time). The essential difference between Maoism and other forms of Marxism is that Mao claimed that peasants should be the essential revolutionary class in China because they were more suited than industrial workers to establish a successful revolution and socialist society in China. Maoism was widely applied as the guiding political and military ideology of the CPC. It evolved with Chairman Mao’s changing views of what he called “the New Democracy,” but its main components are:

Maoism aims to overthrow feudalism and achieve independence from colonialism through a coalition of classes fighting the old ruling order. The original symbolism of the flag of China derived from the concept of the coalition. The largest star symbolized the Communist Party of China’s leadership, and the surrounding four smaller stars symbolize “the bloc of four classes”: proletarian workers, peasants, the petty bourgeoisie (small business owners), and the nationally based capitalists. This was the coalition of classes for Mao’s New Democratic Revolution.

Holding that “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” Maoism emphasized the “revolutionary struggle of the vast majority of people against the exploiting classes and their state structures,” which Mao termed “the People’s war.” Mobilizing large parts of rural populations to revolt against established institutions by engaging in guerrilla warfare, Maoism focused on “surrounding the cities from the countryside.” It viewed the industrial-rural divide as a major division exploited by capitalism, involving industrial urban developed “First World” societies ruling over rural developing “Third World” societies.

Maoism was devoted to the concept of perpetual cultural revolution. The class struggle is continuous, and even intensifies, during socialism. Therefore, a constant struggle against these ideologies and their social roots must be conducted. The revolution’s stated goal was to preserve “true” Communist ideology in the country by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society, and to re-impose Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the Party.

Maoism departed from conventional European-inspired Marxism in that its focus was on the agrarian countryside rather than the industrial urban forces. This is known as agrarian socialism. Although Maoism was critical of urban industrial capitalist powers, it viewed urban industrialization as a prerequisite to expand economic development and socialist reorganization to the countryside, with the goal of rural industrialization that would abolish the distinction between town and countryside.

|

Click and Explore |

|

You can find full transcripts of the most important speeches and writings of Mao Zedong (1920-1976) at the Mao Zedong Reference Archive.

|

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was a sociopolitical movement, set into motion by Mao Zedong, whose stated goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in China by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society. In practice, it led to the persecution and abuse of millions.

In 1958, Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Communist Party of China, called for “grassroots socialism” with the aim of accelerating his plans to turn China into a modern industrialized state. In this spirit, he launched the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign to transform the country’s largely agrarian structure into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization. Main changes in the lives of rural Chinese included the incremental introduction of mandatory agricultural collectivization. Private farming was prohibited and those engaged in it were persecuted and labeled counterrevolutionaries. Restrictions on rural populations were enforced through forced labor, public struggle sessions (a form of public humiliation and torture), and social pressure. Many communities were assigned the production of a single commodity—steel.

A photograph of Chairman Mao in 1951 (Source: Wikimedia)

The Great Leap was a social and economic disaster. Farmers attempted to produce steel on a massive scale, partially relying on backyard furnaces to achieve the production targets set by local cadres. The steel produced was of low quality and largely useless. The Great Leap reduced harvest sizes and led to a decline in the production of most goods, except substandard pig iron and steel. Further, local authorities frequently exaggerated production numbers, hiding and intensifying the problem for several years. Simultaneously, chaos in the collectives, bad weather, and exports of food necessary to secure hard currency resulted in the Great Chinese Famine. The Great Leap resulted in tens of millions of deaths, with estimates ranging from 18 to 55 million.

The Party forced Mao to take major responsibility for the Great Leap’s failure. In 1959, Mao resigned as the President of the People’s Republic of China, China’s de jure head of state, and was succeeded by Liu Shaoqi. By the early 1960s, many of the Great Leap’s economic policies were reversed by initiatives spearheaded by Liu and other moderate pragmatists, who were unenthusiastic about Mao’s utopian visions. By 1962, Mao had effectively withdrawn from economic decision-making and focused much of his time on further developing his contributions to Marxist-Leninist social theory, including the idea of “continuous revolution.” This theory’s goal was to set the stage for Mao to restore his brand of communism and his personal prestige within the Party.

Development of the Revolution

During the early 1960s, State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping favored the idea that Mao be removed from actual power but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role, with the Party upholding his positive contributions to the revolution. Most historians agree that launching the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966 was Mao’s response to Liu and Deng’s increasing political and economic influence (some scholars, however, note that the case for this is overstated).

The Cultural Revolution was a sociopolitical movement, set into motion by Mao, that started in 1966 and ended in 1976 and whose stated goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in China by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and re-imposing Maoism as the dominant ideology within the Party. The Revolution marked the return of Mao to a position of power after the Great Leap Forward.

The Revolution was launched after Mao alleged that bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society at large, aiming to restore capitalism. He insisted that these “revisionists” be removed through violent class struggle. China’s youth responded to Mao’s appeal by forming Red Guard groups around the country. The movement spread into the military, urban workers, and the Communist Party leadership itself. It resulted in widespread factional struggles in all walks of life. In the top leadership, it led to a mass purge of senior officials, most notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. During the same period, Mao’s personality cult grew to immense proportions. Millions of people were persecuted in the violent struggles that ensued across the country and suffered a wide range of abuses, including public humiliation, arbitrary imprisonment, torture, sustained harassment, and seizure of property. A large segment of the population was forcibly displaced, most notably the transfer of urban youth to rural regions during the Down to the Countryside Movement. Mao set the scene for the Cultural Revolution by “cleansing” Beijing of powerful officials of questionable loyalty. His approach was less than transparent. He achieved this purge through newspaper articles, internal meetings, and skillfully employing his network of political allies.

The start of the Cultural Revolution brought huge numbers of Red Guards to Beijing, with all expenses paid by the government. The revolution aimed to destroy the “Four Olds” (old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas) and establish the corresponding “Four News,” which ranged from the changing of names and haircuts to ransacking homes, vandalizing cultural treasures, and desecrating temples. In a few years, countless ancient buildings, artifacts, antiques, books, and paintings were destroyed by the members of the Red Guards. Believing that certain liberal bourgeois elements of society continued to threaten the socialist framework, the Red Guards struggled against authorities at all levels of society and even set up their own tribunals. Chaos reigned in much of the nation.

During the Cultural Revolution, most of the schools and universities in China were closed and the young intellectuals living in cities were ordered to the countryside to be “re-educated” by the peasants, where they performed hard manual labor and other work. Mao officially declared the end of Cultural Revolution in 1969, but its active phase lasted until the death of the military leader Lin Biao in 1971.

A propaganda poster promoting the Cultural Revolution. Chairman Mao is show in the background; members of the Red Guard are in the forefront (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

The ballet, The Red Detachment of Women, was written to support the Cultural Revolution. It tells the story of an abused slave girl on Hainan Island who escapes and becomes a loyal member of a female detachment of Communist soldiers who are fighting against a local warlord. Watch one famous scene where the slave girl is welcomed with joy by members of the Red Guard. This ballet was performed in rural villages throughout China as part of the “re-education” efforts of the communists. |

Consequences

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of much of China’s traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of citizens as well as general economic and social chaos. Millions of lives were ruined during this period as the Cultural Revolution pierced every part of Chinese life. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

The Revolution aimed to get rid of those who allegedly promoted bourgeois ideas as well as those who were seen as coming from an exploitative family background or belonged to one of the Five Black Categories (landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad-influencers or “bad elements,” and rightists). Many people perceived to belong to any of these categories, regardless of guilt or innocence, were publicly denounced, humiliated, and beaten. In their revolutionary fervor, students denounced their teachers and children denounced their parents.

During the Cultural Revolution, libraries full of historical and foreign texts were destroyed and books were burned. Temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, and cemeteries were closed down and sometimes converted to other uses, looted, and destroyed. Among the countless acts of destruction, Red Guards from Beijing Normal University desecrated and badly damaged the burial place of Confucius.

The Cultural Revolution also wreaked havoc on minority cultures in China. In Inner Mongolia, some 790,000 people were persecuted. In Xinjiang, copies of the Qur’an and other books of the Uyghur people were burned. Muslim imams were reportedly paraded around with paint splashed on their bodies. In the ethnic Korean areas of northeast China, language schools were destroyed. In Yunnan Province, the palace of the Dai people’s king was torched and a massacre of Muslim Hui people at the hands of the People’s Liberation Army in Yunnan, known as the Shadian Incident, reportedly claimed over 1,600 lives in 1975.

Although the effects of the Cultural Revolution were disastrous for millions of people in China, there were some positive outcomes, particularly in the rural areas. For example, the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution and the hostility towards the intellectual elite are widely accepted to have damaged the quality of education in China, especially the higher education system. However, some policies also provided many in the rural communities with middle school education for the first time, which facilitated rural economic development in the 1970s and 80s. Similarly, many health personnel were deployed to the countryside. Some farmers were given informal medical training and healthcare centers were established in rural communities. This led to a marked improvement in the health and the life expectancy of the general population.

China after Mao: Deng Xiaoping

The rise of Deng Xiaoping to power after Mao’s death resulted in far-reaching market economy reforms and China opening up to the global trade while maintaining its roots in socialism.

Deng Xiaoping was a Chinese Communist revolutionary and statesman, leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1978 until his retirement in 1989. After Mao Zedong’s death, Deng led China through far-reaching market-economy reforms. While he never held office as the head of state, head of government, or general secretary (the leader of the Communist Party), he nonetheless was the dominant advocate for economic reforms and an opening to the global economy.

A photograph of Deng Xiaoping taken during his visit to the United States in 1979. President Jimmy Carter can be seen in the background. (Source: Wikimedia)

Born into a peasant background, Deng studied and worked in France in the 1920s, where he became fascinated with Marxism-Leninism. He joined the Communist Party of China in 1923. After the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, Deng worked in Tibet and the southwest region to consolidate Communist control. As the party’s Secretary General in the 1950s, he presided over anti-rightist campaigns and became instrumental in China’s economic reconstruction following the Great Leap Forward of 1957-1960. His economic policies, however, were at odds with Mao’s political ideologies and he was purged twice during the Cultural Revolution. Following Mao’s death in 1976, Deng outmaneuvered Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. Inheriting a country beset with social conflict, disenchantment with the Party, and institutional disorder resulting from the policies of the Mao era, Deng became the paramount figure of the “second generation” of Party leadership. Some called him “the architect” of a new brand of thinking that combined socialist ideology with pragmatic market economy whose slogan was “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.”

Deng, along with his closest collaborators Zhao Ziyang, who in 1980 relieved Hua Guofeng as premier, and Hu Yaobang, who in 1981 did the same with the post of party chairman, took power. Their goal was to achieve “four modernizations” – economy, agriculture, scientific and technological development, and national defense. The last position of power retained by Hua Guofeng, chairman of the Central Military Commission, was taken by Deng in 1981.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

In the following excerpt from a speech given in 1984, Deng Xiaoping explains his understanding of “socialism with Chinese characteristics:” What is socialism and what is Marxism? We were not quite clear about this in the past. Marxism attaches utmost importance to developing the productive forces. We have said that socialism is the primary stage of communism and that at the advanced stage the principle of from each according to his ability and to each according to his needs will be applied. This calls for highly developed productive forces and an overwhelming abundance of material wealth. Therefore, the fundamental task for the socialist stage is to develop the productive forces. The superiority of the socialist system is demonstrated, in the final analysis, by faster and greater development of those forces than under the capitalist system. As they develop, the people’s material and cultural life will constantly improve. One of our shortcomings after the founding of the People’s Republic was that we didn’t pay enough attention to developing the productive forces. Socialism means eliminating poverty. Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism. Given that China is still backward, what road can we take to develop the productive forces and raise the people’s standard of living? This brings us back to the question of whether to continue on the socialist road or to stop and turn onto the capitalist road. Capitalism can only enrich less than 10 per cent of the Chinese population; it can never enrich the remaining more than 90 per cent. But if we adhere to socialism and apply the principle of distribution to each according to his work, there will not be excessive disparities in wealth. Consequently, no polarization will occur as our productive forces become developed over the next 20 to 30 years… Proceeding from the realities in China, we must first of all solve the problem of the countryside. Eighty per cent of the population lives in rural areas, and China’s stability depends on the stability of those areas. No matter how successful our work is in the cities, it won’t mean much without a stable base in the countryside. We therefore began by invigorating the economy and adopting an open policy there, so as to bring the initiative of 80 per cent of the population into full play. We adopted this policy at the end of 1978, and after a few years it has produced the desired results. Now the recent Second Session of the Sixth National People’s Congress has decided to shift the focus of reform from the countryside to the cities. The urban reform will include not only industry and commerce but science and technology, education and all other fields of endeavor as well. In short, we shall continue the reform at home and open still wider to the outside world. You can read the full speech here. |

|

China’s Opening Up

Beginning in 1979, economic reforms boosted the market model, while the leaders maintained old Communist-style rhetoric. The commune system was gradually dismantled, and the peasants began to have more freedom to manage the land they cultivated and sell their products on the market. At the same time, China’s economy opened to foreign trade. On January 1, 1979, the United States recognized the People’s Republic of China, and business contacts between China and the West began to grow. The same year, Deng undertook an official visit to the United States, meeting President Jimmy Carter in Washington as well as several congressmen. Deng made it clear that the new Chinese regime’s priorities were economic and technological development. Correspondingly, Sino-Japanese relations also improved significantly. Deng used Japan as an example of a rapidly progressing power that set a good economic example for China.

Special Economic Zones

Since 1980, China has established special economic zones (SEZs): areas where the government of China establishes more free market-oriented economic policies and flexible governmental measures. This allows SEZs to operate under an economic system that is more attractive to foreign and domestic firms than the economic policies in the rest of mainland China. Most notably, the central government in Beijing is not required to authorize foreign and domestic trade in SEZs, and special incentives are offered to attract foreign investors. The development of the five existing SEZs and other areas operating under a preferential economic system continues in China today. Primarily geared to exporting processed goods, the five SEZs are foreign trade-oriented areas which integrate science, innovation, and industry with trade. Foreign firms benefit from preferential policies such as lower tax rates, reduced regulations, and special managerial systems.

Capitalist Economy vs. Socialist System

China’s rapid economic growth under the socialist political system resulted in complex social developments. The 1982 population census revealed the extraordinary growth of the population, which already exceeded one billion people. Deng continued the plans initiated by Hua Guofeng to restrict birth to only one child under the threat of administrative penalty. At the same time, increasing economic freedom emboldened a greater freedom of opinion and critics began to arise.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

In 2019, Amazon Studios produced a documentary discussing the history of the One Child policy in China. Watch the trailer here.

|

In the late 1980s, dissatisfaction with the authoritarian regime and the growing inequalities caused the biggest crisis to Deng’s leadership: the Tiananmen Square protests, the popular national movement inspired by student-led demonstrations in Beijing in 1989. The protests reflected anxieties about the country’s future in the popular consciousness and among the political elite. The economic reforms benefited some groups but seriously disaffected others, and the one-party political system faced a challenge of legitimacy. Common grievances at the time included inflation, limited preparedness of graduates for the new economy, and restrictions on political participation. The students called for democracy, greater accountability, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech, although they were loosely organized, and their goals varied. At the height of the protests, about a million people assembled in the Square.

In this famous photograph, a lone protestor blocks the progress of military tanks on Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1990 (Source: Wikimedia)

As the protests developed, the authorities veered back and forth between conciliatory and hard-liner tactics, exposing deep divisions within the party leadership. By May, a student-led hunger strike galvanized support for the demonstrators around the country and the protests spread to some 400 cities. Ultimately, Deng Xiaoping and other party elders believed the protests to be a political threat and resolved to use force. Party authorities declared martial law on May 20 and mobilized as many as 300,000 troops to Beijing. In what became widely known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, troops with assault rifles and tanks killed at least several hundred demonstrators trying to block the military’s advance towards Tiananmen Square. The number of civilian deaths has been estimated between the hundreds and thousands. The Chinese government was widely condemned internationally for the use of force. Western countries imposed economic sanctions and arms embargoes. In the aftermath of the crackdown, the government conducted widespread arrests of protesters and their supporters, suppressed other protests around China, expelled foreign journalists, and strictly controlled coverage of the events in the domestic press. The police and internal security forces were strengthened. Officials deemed sympathetic to the protests were demoted or purged. More broadly, the suppression temporarily halted the policies of liberalization. Considered a watershed event, the protests also set the limits on political expression in China well into the 21st century.

Officially, Deng decided to retire from top positions when he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989 and retired from the political scene in 1992. China, however, was still in the era of Deng Xiaoping. He continued to be widely regarded as the “paramount leader” of the country, believed to have backroom control. Deng was recognized officially as “the chief architect of China’s economic reforms and China’s socialist modernization.” To the Communist Party, he was believed to have set a good example for communist cadres who refused to retire at old age. He broke earlier conventions of holding offices for life. He was often referred to as simply Comrade Xiaoping, with no title attached.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch a short video that discusses the history of China since the accession to power of Deng Xiaoping produced by the South China Morning Post, a newspaper in Hong Kong.

|