54 INTO THE WORLD OF THE 21st CENTURY

Although the 21st century officially began in the year 2001, many historians believe that the story of the 21st century begins with the pulling down of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism in the early 1990s. For 40 years, the world had been pulled in opposite directions by the two super-powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. The collapse of the Soviet Union left the United States as the world’s only super-power. In 1989, the communist regimes of the Eastern Bloc crumbled as it became clear that the USSR would not intervene militarily to prop them up as it had in the past. Nationalist independence movements exploded across the territory controlled by the Soviet Union until, finally, the entire system fell apart to be replaced by sovereign nations. From the wreckage, fifteen independent states emerged. One of these, Russia itself, reemerged as a distinct country in the process rather than just the most powerful part of a larger union. The ripple effect of the collapse of the Soviet Union was felt around the world. Many developing nations, whose internal affairs had been dominated by the struggle for power and control between the US and USSR, were suddenly set free to determine their own futures. Other nations, like China, who had been overshadowed by the dominance of the world’s super-powers, seized the opportunity to assert themselves on the world stage. Finally, in the void created by the end of Soviet dominance, simmering ethnic tensions exploded into open conflict. Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia fragmented. Chechens living in Russian controlled territory and Abkhazians living in Georgia as well as ethnic Russians in the Baltic states and Ukraine worked to undermine the governments of the states in which they lived.

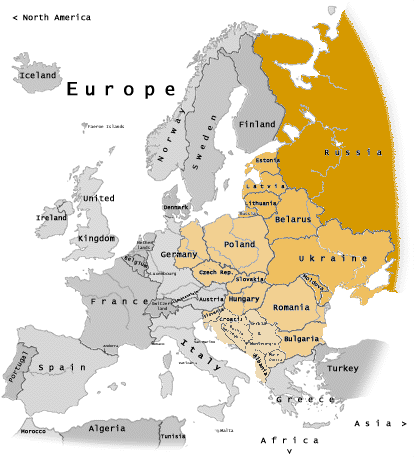

This map shows the pre-1989 division between “Western Europe” (grey) and “Eastern Europe” (orange) superimposed on current European borders. (Source: Wikimedia)

Even though the end of the Cold War did not usher in international peace and tranquility as many had hoped, it did signal the end of communism as a viable economic and political system. In its rhetoric, Soviet Communism had proclaimed itself to be both economically and morally superior to western capitalism. In the aftermath of its fall, the harsh reality of communism’s failure became apparent. In response, the global political culture more widely embraced democracy and human rights as the universal legacy of humankind, rather than the exclusive possession of Europe and the United States.

In Eastern Europe and Russia, communism disappeared completely. And in those nations that still continue to call themselves Communist, many of its economic policies have been abandoned or modified. Since 2006, the Chinese communist party has allowed a free-market economy to operate even while it has maintained political control of the country. Vietnam and Laos have adopted similar strategies. Even Cuba, which had modeled itself closely after the Soviet model, has allowed small businesses and entrepreneurs to operate freely. Of the world’s communist nations, only North Korea has refused to abandon its strict adherence to communist economic policies.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the reforms of Communist nations in the late 20th century by watching Democracy, Authoritarian Capitalism, and China (Crash Course in World History #230).

|

Eastern Europe and Russia

As Eastern European countries emerged from the control of the Soviet control, some like the Czech Republic and Poland, enjoyed success in modernizing their economies and keeping political corruption at bay. For other countries, however, like Russia itself, the 1990s were an unmitigated economic and social disaster as the entire country launched itself into a market economy without planning or oversight. Western consultants, generally associated with international banking firms, convinced Russian politicians in the infancy of its new democracy to institute “shock therapy” by dismantling social programs and government services. While foreign loans accompanied these steps, new industries did not suddenly materialize to fill the enormous gaps in the Russian economy that had been fulfilled by state agencies. Unemployment skyrocketed and the distinctions between legitimate business and illegal or extra-legal trade all but vanished.

The result was an economy that was often synonymous with the black market, gigantic and powerful organized crime syndicates, and the rise of a small number of “oligarchs” to stratospheric levels of wealth and power. One shocking statistic is that fewer than forty individuals controlled about 25% of the Russian economy by the late 1990s. Just as networks of contacts among the Soviet apparatchiks had once been the means of securing a job or accessing state resources, it now became imperative for regular Russian citizens to make connections with either the oligarch-controlled companies or organized crime organizations.

A photograph of Russians protesting unemployment and the lack of social services in 1998 (Source: Wikimedia)

Stability only began to return when a new political strongman, Vladimir Putin, a former agent of the Soviet secret police force (the KGB), was elected president of Russia in 2000. Since that time, Putin has proved a brilliant political strategist, playing on anti-western resentment and Russian nationalism to buoy popular support for his regime, run by “his” political party, United Russia. While opposition political parties are not illegal, and indeed consistently try to make headway in elections, United Russia has been in firm control of the entire Russian political apparatus since shortly after Putin’s election. Opposition figures are regularly harassed or imprisoned, and many opposition figures have also been murdered. Some of the most egregious excesses of the oligarchs of the 1990s were also reined in, while some oligarchs were instead incorporated into the United Russia power structure.

A photograph of Vladimir Putin in 2020 (Source: Wikimedia)

Unlike many of the authoritarian rulers of Russia in the past, Putin was (and remains) hugely popular among Russians. Media control has played a large part in that popularity, of course, but much of Putin’s popularity is also tied to the wealth that flooded into Russia after 2000 as oil prices rose. While most of that wealth went to enrich the existing Russian elites (along with some of Putin’s personal friends, who made fortunes in businesses tied to the state), it also served as a source of pride for many Russians who saw little direct benefit. Further boosts to his popularity came from Russia’s invasion of the small republic of Georgia in 2008 and, especially, its invasion and subsequent annexation of the Crimean Peninsula from the Ukraine in 2014. While the latter prompted western sanctions and protests, it was successful in supporting Putin’s power in Russia itself.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Understand life in today’s Russia by watching a special presentation of the PBS NewsHour entitled “Inside Putin’s Russia.”

|

Western Europe

In the post-World War II era, most of the nations of western Europe entered into various international groups that sought to improve economic relations and trade between the member nations. These relationships culminated in the creation of the European Community (EC) in 1967, essentially an economic alliance and trade zone between most of the nations of non-communist Europe. Despite various setbacks, the EC steadily added new members into the 1980s. Its leadership also began to discuss the possibility of moving toward an even more inclusive model for Europe, one in which not just trade but currency, law, and policy might be more closely aligned between countries. That vision of a united Europe was originally conceived in large part in hopes of creating a power-bloc to rival the two superpowers of the Cold War, but it also encompassed a moral vision of an advanced, rational economic and political system, in contrast to the conflicts that had so often characterized Europe in the past.

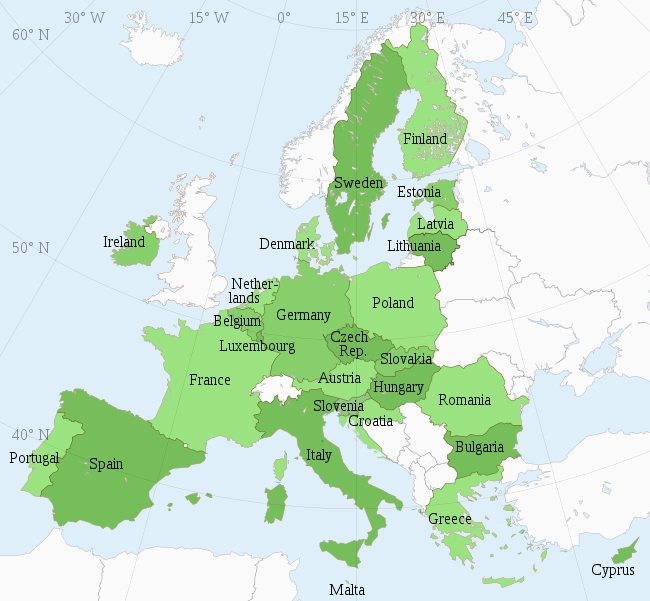

A map showing the member states of the European Union in 2020 (Source: Wikimedia)

The EC officially became the European Union in 1993, and various member nations of the former EC voted to join in the following years. Over time, passport controls at borders between the member states of the EU were eliminated entirely. The member nations agreed to policies meant to ensure civil rights throughout the Union, as well as economic stipulations (e.g., limitations on national debt) meant to foster overall prosperity. Most spectacularly, at the start of 2002, the Euro became the official currency of the entire EU except for Great Britain, which chose to continue to use the British Pound.

The period between 2002 and 2008 was one of relative success for the architects of the EU. The economies of Eastern European countries in particular accelerated, along with a few unexpected western countries like Ireland. Loans from wealthier members to poorer ones, the latter generally clustered along the Mediterranean, meant that none of the countries of the “Eurozone” lagged too far behind economically. While the end of passport controls at borders worried some, there was no general immigration crisis to speak of.

However, a global financial crisis in 2008 brought this period of stability to an end. Since 2008, the EU has been fraught with economic problems. The major issue is that the member nations cannot control their own economies past a certain point – they cannot devalue currency to deal with inflation, they are nominally prevented from allowing their own national debts to exceed a certain level of their Gross Domestic Product (3%, at least in theory), and so on. The result is that it is terrifically difficult for countries with weaker economies such as Spain, Italy, or Greece, to maintain or restore economic stability.

In the most shocking development to undermine the coherence and stability of the EU as a whole, Great Britain narrowly voted to leave the Union entirely in 2016. In what analysts largely interpreted as a protest vote against not just the EU itself, but of complacent British politicians whose interests seemed squarely focused on London’s welfare over that of the rest of the country, a slim majority of Britons voted to end their country’s membership in the Union. Years of bitter political struggle ensued, but the country finally left in early 2020. The political and economic consequences remain unclear: the British economy has been deeply enmeshed with that of the EU nations since the end of World War II, and it is simply unknown what effect its “Brexit” will have in the long run.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May of Great Britain sent a letter to the President of the European Union in which she communicated the decision of her country to official leave the European Union. In this letter, she said: On 23 June last year, the people of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. As I have said before, that decision was no rejection of the values we share as fellow Europeans. Nor was it an attempt to do harm to the European Union or any of the remaining member states. On the contrary, the United Kingdom wants the European Union to succeed and prosper. Instead, the referendum was a vote to restore, as we see it, our national self-determination. We are leaving the European Union, but we are not leaving Europe — and we want to remain committed partners and allies to our friends across the continent… Today, therefore, I am writing to give effect to the democratic decision of the people of the United Kingdom. I hereby notify the European Council in accordance with Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union of the United Kingdom’s intention to withdraw from the European Union. You can read the entire letter here. |

|

The Middle East

The Middle East has remained one of the most conflicted regions in the post-Cold War world. Much of the instability has revolved around three interrelated factors: the Middle East’s role in global politics, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the vast oil reserves of the region. In turn, the United States played a significant role in shaping the region’s politics and conflicts.

This contemporary map of the Middle East shows the existing national borders (Source: Wikimedia)

During the Cold War the Middle East was constantly implicated in American policies directed to curtail the (often imaginary) threat of Soviet expansion. The US government tended to support political regimes that could serve as reliable clients regardless of the political orientation of the regime in question or that regime’s relationship with its neighbors. First and foremost, the US drew close to Israel because of Israel’s antipathy to the Soviet Union and its own powerful military. Israel’s crushing victory in the 1967 Six-Day War demonstrated to American politicians that it was a powerhouse worth cultivating, and in the decades that followed the governing assumption of American – Israeli relations was that Israel was the most reliable powerful partner supporting American interests. Part of that sympathy was also born out of respect for the fact that Israel’s government is democratic and that it has a thriving civil society.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Learn more about the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict by visiting the Global Conflict Tracker website sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations.

|

Simultaneously, however, the US supported Arab and Persian regimes that were anything but democratic. The Iranian regime under the Pahlavi dynasty was restored to power through an American-sponsored coup in 1953, with the democratically elected prime minister Muhammad Mosaddegh expelled from office. The Iranian Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi ruled Iran as a loyal American client for the next 26 years while suppressing dissent through a brutal secret police force. The Iranian regime purchased enormous quantities of American arms (50% of American arms sales were to Iran in the mid-1970s) and kept the oil flowing to the global market. Iranian society was highly educated, and its economy thrived, but its government was an oppressive autocracy.

A photograph of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi in 1973 (Source: Wikimedia)

Likewise, the equally autocratic monarchy of Saudi Arabia emerged as the third “pillar” in the US’s Middle Eastern clientage system. Despite its religious policy being based on Wahhabism, the most puritanical and rigid interpretation of Islam in the Sunni world, Saudi Arabia was welcomed by American politicians as another useful foothold in the region that happened to produce a vast quantity of oil. Clearly, opposition to Soviet communism and access to oil proved far more important from a US policy perspective than did the lack of representative government or civil rights among its clients.

This status quo was torn apart in 1979 by the Iranian Revolution. What began as a coalition of intellectuals, students, workers, and clerics opposed to the oppressive regime of the Shah was overtaken by the most fanatical branch of the Iranian Shia clergy under the leadership of the Ayatollah (“eye of God”) Ruhollah Khomeini. When the dust settled from the revolution, the Ayatollah had become the official head of state and Iran had become a hybrid democratic-theological nation: the Islamic Republic of Iran. The new government featured an elected parliament and equality before the law (significantly, women enjoy full political rights in Iran, unlike in some other Middle Eastern nations like Saudi Arabia), but the Ayatollah had final say in directing politics, intervening when he felt that Shia principles were threatened. Deep-seated resentment among Iranians toward the US for the latter’s long support of the Shah’s regime became official policy in the new state, and in turn the US was swift to vilify the new regime.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the Iranian Revolution by watching Iran’s Revolutions (Crash Course in World History #226).

|

The 1980s and 1990s saw a botched Israeli invasion of Lebanon, an ongoing military debacle for the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, and a full-scale war between the new Islamic Republic of Iran and its neighbor, Iraq. Ruled by a secular nationalist faction, the Ba’ath Party, since 1968, Iraq represented yet another form of autocracy in the region. Saddam Hussein, the military leader at the head of the Ba’ath Party, launched the Iran-Iraq War as a straightforward territorial grab. The United States supported both sides during the war at different points despite its avowed opposition to the Iranian regime. In the end, the war sputtered to a bloody stalemate in 1988 after over a million people had lost their lives.

Just two years later, Iraq invaded the neighboring country of Kuwait and the United States (fearing the threat to oil supplies and now regarding Hussein’s regime as dangerously unpredictable) led a coalition of United Nations forces to expel it. The subsequent Gulf War was an easy victory for the US and its allies, even as the USSR spiraled toward its messy demise as communism collapsed in Eastern Europe. The early 1990s thus saw the United States in a position of unparalleled power and influence in the Middle East, with every country either its client and ally (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Israel) or hostile but impotent to threaten US interests (e.g. Iran, Iraq). American elites subscribed to what President George H. W. Bush described as the “New World Order”: America would be the world’s policeman, overseeing a global market economy, and holding rogue states in check with the vast strength of American military power.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

The following is an excerpt of President George H.W. Bush’s speech before a joint session of Congress on Sept. 11, 1990, in which he describes his vision of a new world order amid the Persian Gulf crisis: We stand today at a unique and extraordinary moment. The crisis in the Persian Gulf, as grave as it is, also offers a rare opportunity to move toward an historic period of cooperation… Out of these troubled times, our fifth objective — a new world order — can emerge: a new era — freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice, and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, East and West, North and South, can prosper and live in harmony… Recent events have surely proven that there is no substitute for American leadership. In the face of tyranny, let no one doubt American credibility and reliability. Let no one doubt our staying power. We will stand by our friends. You can read the full text of President Bush’s speech here. |

|

Instead, the world was shocked when fundamentalist Muslim terrorists, not agents of a nation, hijacked and crashed airliners into the World Trade Center towers in New York City and into the Pentagon (the headquarters of the American military) on September 11, 2001. Fueled by hatred toward the US for its ongoing support of Israel against the Palestinian demand for sovereignty and for the decades of US meddling in Middle Eastern politics, the terrorist group Al Qaeda succeeded in the most audacious and destructive terrorist attacks in modern history. President George W. Bush (son of the first President Bush) vowed a global “War on Terror” that has, almost two decades later, no apparent end in sight. The American military swiftly invaded Afghanistan, ruled by an extremist Sunni Muslim faction known as the Taliban, for sheltering Al Qaeda. American forces easily toppled the Taliban but failed to destroy it or Al Qaeda.

In a fateful decision with continuing reverberations in the present, the George W. Bush presidency used the War on Terror as an excuse to settle “unfinished business” in Iraq as well. Despite the complete lack of ties between Hussein’s regime and Al Qaeda, and despite the absence of the “weapons of mass destruction” used as the official excuse for war, the US launched a full-scale invasion in 2002 to topple Hussein. That much was easily accomplished, as once again the Iraqi military proved completely unable to hold back American forces. Within months, however, Iraq devolved into a state of murderous anarchy as former leaders of the Ba’ath Party (thrown out of office by American forces), local Islamic clerics, and members of different tribal or ethnic groups led rival insurgencies against both the occupying American military and their own Iraqi rivals. The Iraq War thus became a costly military occupation rather than an easy regime change, and in the following years the internecine violence and American attempts to suppress Iraqi insurgents led to well over a million deaths (estimates are notoriously difficult to verify, but the death toll might actually be over two million). A 2018 US Army analysis of the war glumly concluded that the closest thing to a winner to emerge from the Iraq War was, ironically, Iran, which used the anarchic aftermath of the invasion to exert tremendous influence in the region.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the history of Islam and Politics by watching Crash Course in World History #216.

|

The terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001 are part of a larger geo-political movement frequently referred to as “radical Islam.” The rise of radical Islam in the 21st century is a result of many complex factors, including Western colonialism in Muslim-dominated regions, state-sponsored aggressive popularization of ultra-orthodox interpretations of Islam, Western and pro-Western Muslim support for Islamist groups during the Cold War, and victories of Islamist groups over pro-Western politicians and factions in the Middle East. For Islamists, the primary threat of the West is cultural rather than political or economic. Islamists assume that cultural dependency robs one of faith and identity and thus destroys Islam and the Islamic community far more effectively than political rule.

In the late 20th century, an Islamic revival or Islamic awakening developed in the Muslim world, manifested in greater religious piety and growing adoption of Islamic culture. Two of the most important events that fueled or inspired the resurgence were the Arab oil embargo and subsequent quadrupling of the price of oil in the mid-1970s and the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which established an Islamic republic in Iran under Ayatollah Khomeini. The first created a flow of many billions of dollars from Saudi Arabia to fund Islamic books, scholarships, fellowships, and mosques around the world. The second undermined the assumption that Westernization strengthened Muslim countries and was the irreversible trend of the future.

The revival is a reversal of the Westernization approach common among Arab and Asian governments earlier in the 20th century. Although religious extremism and attacks on civilians and military targets represent only a small part of the movement, the revival has seen a proliferation of Islamic extremist groups in the Middle East and elsewhere in the Muslim world. They have voiced their anger at perceived exploitation as well as materialism, Westernization, democracy, and modernity, which are most commonly associated with accepting Western secular beliefs and values. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq described in early paragraphs failed to stabilize the political situation in the Middle East and contributed to ongoing civil conflicts, with counterterrorism experts arguing that they created circumstances beneficial to the escalation of radical Islam.

Thus, the shock waves of Middle Eastern conflict reverberated around the globe, inspiring the growth of international terrorist groups on the one hand and racist and Islamophobic political parties on the other. To cite just the most important examples, the US invasion of Iraq in 2002 inadvertently prompted a massive increase in recruitment for anti-western terrorist organizations (many of which drew from disaffected EU citizens of Middle Eastern and North African ancestry). The Arab Spring of 2010 led to a brief moment of hope that new democracies might take the place of military dictatorships in countries like Libya, Egypt, and Syria, only to see authoritarian regimes or parties reassert control. Syria in particular spiraled into a horrendously bloody civil war in 2010, prompting millions of Syrian civilians to flee the country. Turkey, one of the most venerable democracies in the region since its foundation as a modern state in the aftermath of World War I, has seen its president Recep Tayyip Erdogan steadily assert greater authority over the press and the judiciary. The two other regional powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, carry on a proxy war in Yemen and fund rival paramilitary (often considered terrorist) groups across the region. Israel, meanwhile, continues to face both regional hostility and internal threats from desperate Palestinian insurgents, responding by tightening its control over the nominally autonomous Palestinian regions of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

In Europe, fleeing Middle Eastern (and to a lesser extent, African) refugees seeking the infinitely greater stability and opportunity available to them abroad have brought about a resurgence of far right and, in many cases, openly neo-fascist politics. While fascistic parties like France’s National Front have existed since the 1960s, they remained basically marginal and demonized for most of their history. Since 2010, far right parties have grown steadily in importance, seeing their share of each country’s electorate increase as worries about the impact of immigration drives voters to embrace nativist, crypto-racist political messages. Even some citizens who do not harbor openly racist views have come to be attracted to the new right, since mainstream political parties often seem to represent only the interests of out-of-touch social elites (again, Brexit serves as the starkest demonstration of voter resentment translating into a shocking political result).

While interpretations of events since the start of the twenty-first century will necessarily vary, what seems clear is that both the postwar consensus between center-left and center-right politics is all but a dead letter. Likewise, fascism can no longer be considered a terrible historical error that is, fortunately, now dead and gone; it has lurched back onto the world stage. A widespread sense of anger, disillusionment, and resentment haunts politics throughout the world.

Predicting the future is a fool’s errand, and one that historians in particular are generally hesitant to engage in. That said, if nothing else, history provides both examples and counterexamples of things that have happened in the past that can, and should, serve as warnings for the present. As this survey of world history since 1500 has demonstrated, much of history has been governed by greed, indifference to human suffering, and the lust for power. It can be hoped that studying the consequences of those factors and the actions inspired by them might prove to be an antidote to their appeal, and hopefully to their purported legitimacy as political motivations.