42 NORTH AMERICA

THE FAR NORTH (CANADA) AND ALASKA

Alaska’s northwest contained 24 Eskimo groups, all speaking related tongues. Unlike their European and Siberian counterparts, these Americans relied more on sea mammals than on the new world reindeer (caribou). Seals, walruses, and sea-lions supplied food, clothes, boats, tents, and oil for lamps. Tendons were used for sewing, and bones took the place of wood. The Eskimos introduced umiaks (large, open, skin boats) and the toggle-headed harpoon to the world.

The century opened with bloody warfare for the small Russian settlement at Fort St. Michael on Baranov Island, when the Tlingit Indians fought against Russian aggression in 1802. Two years later, the Russians responded and forced the Tlingits to withdraw. The Russians then built a new fort, and in the years that followed, the missionary priest Veniaminov Innocent built a cathedral, started a seminary, saved the Tlingits from a small-pox epidemic by vaccination, taught the Aleuts carpentry, blacksmithing, and brickmaking, created an Aleut alphabet. and with that translated the Gospels. At the time, commerce with San Francisco was brisk, particularly during the latter’s gold-rush days. Among other things, 20,000 tons of Alaskan ice, packed in sawdust, was sold in San Francisco at $35 a ton. The zenith of Russian culture at Sitka was in the year 1820

A photograph of men killing fur seals on Saint Paul Island in Alaska, 1890s (Source: Wikimedia)

The various clans of the Tlingit dominated the hinterland, and thus controlled the principal source of Russian food supply. Frequently these clans mounted crippling raids against the Russian mainland settlements, some as late as 1866. Supply ships from Russia had to go around the Cape of Good Hope, and in some years none arrived. Many Russians died of scurvy before they learned that potatoes and other vegetables could be grown in the far north. At one point, the Russians attempted to solve their grain problem by establishing Fort Ross, only 90 miles north of the Spanish mission of San Francisco. However, because the area was not very fertile, they sold it to the American John Sutter in 1841.

The Russians enslaved the Aleuts, forcing half of all males between the ages of 18 and 50 to work for very meager compensation. By this policy, along with disease, the Aleut population was reduced to 1/10th of the original, and the Eskimos on the mainland was reduced by half. A massive seal fur industry resulted when a machine was developed which removed the outer layer of bristly guard hairs from the animal. A Moscow journal of 1835 boasted that, between 1786 and 1832, over three million northern fur seals were killed.

The Russians agreed to sell Alaska’s 375 million acres to the United States in 1867 for 7.2 million dollars. That purchase, arranged by Secretary of State William Henry Seward of the Andrew Johnson administration, resulted in the name “Seward’s Folly” for that region for many years. All was forgiven at the end of the 19th century when the Klondike and Nome gold rushes developed.

GREENLAND

Central Greenland remained the most inhospitable of all Arctic areas. Eskimos dwelt along the southern coasts, both east and west, with a hybrid Eskimo-Danish culture. The Congress of Vienna in 1815, which had granted Norway independence from Denmark, allowed Greenland to remain under Danish control. Administration was poor, however, and, among other troubles, the Eskimos were troubled by a high incidence of tuberculosis. In far northwest Greenland, a group known simply as Polar Eskimos lived in complete isolation, using sea-mammal bones for sled runners, and using nets to catch cliff-dwelling birds. There were about 150 people there when Europeans made contact in 1818.

CANADA

Arctic Canada had a mixture of Inuit people living chiefly north of the tree line, and Northern Athabaskan peoples who lived just south of that region. These people walked hundreds of miles each summer after the caribou herds. In winter, they used snowshoes and lived in domed caribou-skin tents or log and moss houses. They traded with the Eskimos. The Inuit people lived on the Arctic Ocean coastline from Beaufort Sea to the Baffin Bay and Davis Strait as well as on the northern shores of Hudson Bay.

In 1825, British North America consisted of two major areas: the six settled provinces of Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Lower and Upper Canadas and the remaining territory from Hudson’s Bay west to the Pacific. Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick were known as the Maritime provinces. Over 600,000 people, primarily French-speaking, people lived in Lower Canada (which was later called Quebec). In 1841, upper Canada (which later became known as Ontario) had a population of over 450,000. The western territory was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company with the British government keeping some authority. Each province was ruled by a member of the local gentry who pledged their support to the appointed governor.

Occasionally an attempt to gain independence sprouted, such as the unsuccessful revolt promoted by Louis Joseph Papineau in 1837 in Lower Canada. In Ontario, an uprising of 1836 led by William Lyon MacKenzie of Toronto and Marshall Bidwell, a fugitive from the United States, marched on Toronto where they were dispersed by British troops. In May of 1838, Queen Victoria sent John Lambton, the Earl of Durham, to be commissioner of British North America. His recommendations convinced the British Parliament to pass the Act of Union in 1840. This Act merged the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada into one colony known as the Province of Canada. Responsible government was established for all provinces of British North America by 1849. The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending Canada’s border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858). The Alaska Purchase of 1867 by the United States established the Canadian border along the Pacific coast.

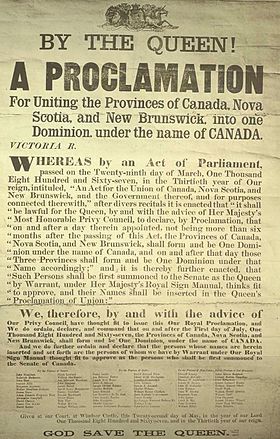

Following several constitutional conferences, the Constitution Act officially proclaimed the Canadian Dominion on July 1, 1867, with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. The province of Manitoba was created in July 1870. British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had been united in 1866) joined the Dominion in 1871, while Prince Edward Island joined in 1873.

The official Proclamation of the Canadian Confederation in 1867 (Source: Wikimedia)

The formation of the Dominion resulted from three forces, the rise of Canadian nationalism, a desire of British liberals to slough off colonial responsibilities, and the ambition of some elements in the United States to annex Canada. The Constitution granted to the Dominion reserved the powers of government in the Parliament at Ottawa, but it failed to quench provincialism, particularly among the French population in Quebec, who resented the English attempts to put an end to their language and culture.

Between 1871 and 1896, almost one quarter of the Canadian population migrated southward to live in the United States. To open the West to European settlers, three transcontinental railways were constructed (including the Canadian Pacific Railway) by an act of Parliament. In 1898, during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, Parliament created the Yukon Territory. Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.

Like the United States, Canada had a depression in 1873, which lasted at least 20 years and slowed the growth of that country considerably. It recovered only after the completion of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885. The election of 1896 brought Sir Wilfrid, a French-Canadian lawyer, to head the government as premier, and his long administration saw a wave of prosperity as the prairie provinces developed with their new railroad transportation system. Still, at the end of the century great expanses of land in Canada were uninhabited. Lands occupied by 1900 included a narrow strip along the St. Lawrence River, Montreal, and the eastern Great Lakes, then southern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and southeastern Alberta, with Winnipeg as a wheat center being the only city of over 100,000 west of Toronto.

THE UNITED STATES

Note that because this is a textbook dedicated to world history, this section will concentrate on those events in US history that most directly impacted world history. Students who wish to learn more about the history of the United States are encouraged to take a US history course!

The Louisiana Purchase (1803)

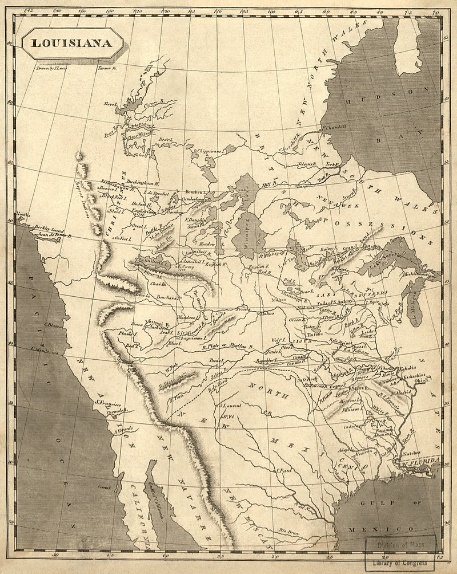

There were many reasons for Napoleon’s sale of the Louisiana Territory – his need for money, his fear that Britain would otherwise soon take it from him, and his General Leclerc’s recent loss of 24,000 men over a 9-month period to disease, and the existence of 500,000 black Haitians who refused to be enslaved and instead fought for their freedom against French tyranny. The legality of the sale was questionable, however, as the native peoples who lived in the region were not consulted, and their rights were not considered. The area sold included the whole watershed of the Mississippi, comprising the present states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, both the Dakotas. Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, – that is, one-third of North America. The sale price of $15,000,000 actually amounted to less than four cents an acre.

An 1804 map showing the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase (Source: Wikimedia)

The boundaries of the Louisiana territory were actually very poorly defined except in the east and south, where the Mississippi and Rio Grande served as “natural barriers.” On the west, the border was the Rocky Mountains. There was less definition in the North, with mention of a border in the vicinity of the origin of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Even after the United States acquired Missouri in the Louisiana Purchase, French influence remained dominant in that region. But Americans began to filter in, particularly in the regions of the lead mines at Ste. Genevieve and Potosi. By the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, St. Louis was already notable as the gateway to the Far West. Later St. Joseph, Missouri was the supply center for the gold rush “49ers” and over 50,000 emigrants went through that city of only 3,000 permanent people.

The Settling of the Oregon Territory

The original Oregon Territory included the present-day states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and the province of British Columbia. The final border settlement with Great Britain was negotiated in June 1846 under President Polk’s administration. Backwoodsmen from Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, and Kentucky made up most of the early white settlers who had been led there by the Rocky Mountain beaver hunters known as “mountain men.” Conflict between native peoples and the incoming settlers erupted from time to time, including the Cayuse War of 1847. The Cayuse Indians, who blamed missionaries for an outbreak of smallpox, attacked the Whitman Mission near present day Walla Wall, Washington. Over the next few years, the Provisional Government of Oregon and later the United States Army waged war against Indians east of the Cascades. This was the first of several wars between Native Americans and American settlers in the region that would lead to the negotiations between the United States and Native Americans of the Columbia Plateau, creating a number of Indian reservations.

The Spanish American War

In 1897 Cuba revolted against Spanish control. American journalists, such as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, in a race to increase circulation, published sensationalized tales of atrocities and Cuban concentration camps. Soon there was a cry to “do something” about Cuba. When the U.S.S. Maine battleship was mysteriously blown up in Havana harbor, the clamor for war with Spain became more than President McKinley could withstand. Thus, instead of accepting a peaceful solution offered by Spain, which had included ceding Cuba to the U.S., McKinley supported Congress’ declaration of war against Spain in April 1898. The American Navy was engaged immediately, with one Atlantic squadron blockading Havana and another protecting the U.S. coast. Commodore Dewey took the Pacific fleet into Manila Bay in the Philippines and, without losing a single man, destroyed the Spanish fleet. After 10 weeks of fighting, the U.S. wrested an American empire from Spain. When the Spanish navy sailed out of Santiago Bay to be destroyed by the guns of Admiral Sampson’s Atlantic squadron in July 1898, the war was over. At the formal Treaty of Paris in the fall of that year, both Cuba and Puerto Rico, as well as the Philippines, became U.S. possessions.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

Many Americans opposed the economic and military expansion of the United States after the Spanish-American. Mark Twain was one of the leading critics and in the following passage he argues the imperialism is contrary to the principles the United States was built on: I left these shores, at Vancouver, a red-hot imperialist. I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific. It seemed tiresome and tame for it to content itself with the Rockies. Why not spread its wings over the Philippines, I asked myself? And I thought it would be a real good thing to do. I said to myself, here are a people who have suffered for three centuries. We can make them as free as ourselves, give them a government and country of their own, put a miniature of the American constitution afloat in the Pacific, start a brand new republic to take its place among the free nations of the world. It seemed to me a great task to which we had addressed ourselves. But I have thought some more, since then, and I have read carefully the treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land. You can read more of Twain’s anti-imperialism writings here. |

|

Native Peoples

The story of Native peoples in the early part of the 19th century is related to the insatiable demands of land craving Americans and President Jackson’s Indian policies which resulted in the attempt to remove all Indians to regions west of the Mississippi. This began in the Ohio Valley and the lower South. The enactment of harsh removal policies resulted in great suffering and death for Native peoples. From 1853 to 1856, there were fifty-two treaties signed, mostly with Indian nations west of the Mississippi, resulting in the addition of 174 million acres to the national domain. More than two-hundred thousand Indians lived between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains at the beginning of the 18th century.

The Indian story in the latter half of the 19th century is that of the Great Plains tribes and their attempts to prevent American settlements. The Sioux, Blackfoot, Crow, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Nez Perce, Comanche, Apache, Ute, and Kiowa were all well-armed and had swift horses. The wanton destruction of the buffalo, the Colt six-shooter, and the white man’s diseases were all fatal to the plains Indians. Some of the tribes lost as many as 50% of their people.

The various tribes occupied and roamed over large territories at times. The Shoshones of Wyoming territory were linguistically and culturally related to the Utes and Paiutes and were actually great warriors against their Indian enemies (Sioux, Crows, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, and Arapahos), but they made friends with the whites of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and later helped the Mormons travel safely. Fort Washakie was named after the great Shoshone chief. The Blackfoot occupied part of Wyoming and Montana territory, while the Nez Perce were primarily in Idaho. The Utes, some of whom were also friendly to whites, were primarily in Colorado and Utah, where there were no U.S. forts.

The Cheyenne and Sioux were more widely distributed, with the latter especially spread from the Dakota territory through Montana, Wyoming, and northern Nebraska. The U.S. had many forts in those areas, including Forts Buford, Abraham Lincoln, Yates, Meade, and Randall in the Dakota Territory, Fort Kearney in Nebraska, and Fort Ellis in Montana. Chief Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Sioux band warrior and Crazy Horse was an Oglala Sioux. In the 1860s, the United States convinced the Hunkpapas to settle on a large reservation (along with some Cheyenne and Arapaho clans) encompassing the entire western half of South Dakota and the Powder River country to west of the Big Horn Mountains. This “Indian Territory” was guaranteed to be “off limits” to all white settlers by the Treaty of Laramie. This guarantee, however, was withdrawn when gold was found in the Black Hills. By 1875, there were over 1000 prospectors there.

When Chief Sitting Bull ignored orders to go to a reservation, General Custer led one of the three forces of the U.S. to force Indian compliance. In the battle that followed, Custer was killed, and the core of the 7th Cavalry was destroyed. Later the Sioux were defeated by Colonel Nelson Miles, and Sitting Bull was taken prisoner. After the capture of Sitting Bull, the Sioux Chief Big Foot, with 300 followers, escaped to the Badlands of South Dakota. They, too, were captured and taken to Wounded Knee Creek. When the soldiers were attempting to disarm the Indians, gun fire broke out, the Indians were massacred, and the bodies left on the ground to freeze.

A photograph of Chief Sitting Bull taken in 1883 (Source: Wikimedia)

By 1870 a new tanning process made buffalo hides commercially viable, and therefore buffalo hunting became a full-time business. At the same time there appeared the high-powered Sharps’ rifle that could kill a full-grown buffalo at 500 yards. A top marksman might kill 200 a day in the Texas panhandle. This marked the end of the buffalo and of the remaining Indians. Buffalo slaughter at more than a million a year meant that by 1886 only about 1000 remained on the plains.

In the American southwest, approximately 7000 Apaches lived in Arizona and New Mexico. There were several bands – the White Mountain group, the Yavapai, the Mimbres, and the Chiricahuas (also known as the White Apaches) being the most numerous. The latter group was perhaps the most formidable and was led by Chief Cochise. The Apache bows were lethal at one-hundred yards, and they used slings, which could hurl stones one-hundred and fifty yards, as well as war clubs and lances. Trained as long-distance runners, they could cover seventy miles a day on foot in tough terrain. By the 1870s, there were 10,000 white miners, ranchers, and townsmen in Arizona, and, by 1880, the number had risen to 37,000, about ten times the Indian population. In the 1880s, 5000 Apaches were forced on to the San Carlos reservation in southern Arizona where they were required to farm. Geronimo repeatedly escaped to Mexico and returned to raid. In 1886, General Nelson Miles took 5000 troops to hunt him down. Geronimo finally surrendered after his family had been sent to Florida. In 1894, he and the remaining Chiricahuas were taken to Ft. Sill, where most of them soon died of disease.

In the far west, the Yuroks and Hupa peoples of northern California, like the northwest coastal Indians, were highly sophisticated, using bows and arrows, body armor of thick elk hide, and dugout canoes with six-eight-foot paddles that could even be used in the ocean. They ate salmon, mussels, seaweed (for salt), whale meat, and acorns. The latter were dried, pounded into meal, treated with hot water to remove the tannic acid, and then cooked in closely woven baskets, with stirring, until a tasteless gruel resulted. They grew and smoked tobacco. Although those two California tribes spoke entirely different languages, they were friendly and cooperative with each other.

MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA, AND THE CARIBBEAN

In the first decades of the 19th century, the political ideas which had given rise to revolutions in the United States, France, and Haiti gave birth to independence movements throughout this region. As was the case in British North America, native-born elites (called criollos) grew increasingly resentful of Spanish attempts to limit their economic freedom. High taxes and tariffs were especially onerous. Criollo intellectuals were familiar with the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and began to espouse notions of freedom, popular sovereignty, and republican government.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about Latin American revolutions by watching Crash Course in World History #31.

|

The movement towards freedom in Latin America moved at a slower pace than that which had transpired in the North. The Spanish had given their American subjects less independence than the British had theirs, so the tradition of self-government was less developed. Latin American society was also more sharply divided by class. This meant that the criollo elite had established few cultural and economic connections with the more populous Native Americans, people of African ancestry, and those of mixed race.

The movement towards independence was intensified when the Spanish monarchy were thrown into disarray as a result of Napoleon’s rise to power. The resulting power vacuum throughout Latin America gave impetus to the independence movements so that, by 1826, all of the states of Latin America were independent of Spanish control.

The first stages of revolution began in Mexico in 1810 as an insurrection of peasants enraged by high food prices and the lack of economic opportunity. Two priests led the movement, Miguel Hidalgo and José Maria Morelos. Members of the creole elite, alarmed by what they perceived to be the social radicalism of the movement, raised an army, and effectively crushed the rebellion. The decision of the criollo elite to oppose the Hidalgo-Morelos rebellion illustrates a fundamental pattern present in all of the 19th century independence movements in Latin America. Elites were frustrated by and thus opposed to what they perceived to be the tyrannical actions of their European overlords. At the same time, elites were frightened by the threat of ‘revolution from below’ – of radical social change that would alter their status and thus their power. Both the French and Haitian revolutions had demonstrated (to the elites) the danger of revolutions spinning out of control. They thus were determined to both free themselves of European control while maintaining their dominance over the lower classes of society.

An oil painting of Agustín de Iturbide (Source: Wikimedia)

The complexity of the situation confronting the creole elites is demonstrated by the fact that Agustín de Iturbide who had been a captain in the army that defeated the peasant rebellion was the leader of a group of conservative rebels who declared independence for Mexico from Spain. Iturbide proclaimed three principles, or “guarantees,” for Mexican independence from Spain. Mexico would be an independent monarchy governed by King Ferdinand VII, another Bourbon prince, or some other conservative European prince; criollos would be given equal rights and privileges to peninsulares (those born in Spain); and the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico would retain its privileges and position as the established religion of the land. After convincing his troops to accept the principles, which were promulgated on February 24, 1821, as the Plan of Iguala, a new army, the Army of the Three Guarantees, was placed under Iturbide’s command to enforce the Plan of Iguala. The plan was so broadly based that it pleased both patriots and loyalists. The goal of independence and the protection of Roman Catholicism brought together all factions.

Iturbide’s army was joined by rebel forces from all over Mexico. When the rebels’ victory became certain, Spain’s governor in Mexico resigned. On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which recognized Mexican independence. On September 27, 1821, the Army of the Three Guarantees entered Mexico City, and the following day Iturbide proclaimed the independence of the Mexican Empire, as New Spain would henceforth be called.

After independence, Mexican politics were chaotic. The presidency changed hands 75 times in the next 55 years (1821–76). The newly independent nation was in dire straits after 11 years of war. No plans or guidelines were established by the revolutionaries, so internal struggles for control of the government ensued. Mexico suffered a complete lack of funds to administer a large country and faced the threats of emerging internal rebellions and of invasion by Spanish forces from their base in nearby Cuba. In addition, war with the United States in 1847 resulted in a significant loss of territory (present day Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California).

In 1861, France invaded Mexico under the leadership of Napoleon III. Napoleon wanted the silver that could be mined in Mexico to finance his empire. Napoleon built a coalition with Spain and Britain while the U.S. was deeply engaged in its civil war. However, when the British and Spanish discovered that France planned to seize all of Mexico, they quickly withdrew from the coalition.

The French invasion resulted in the Second Mexican Empire. In Mexico, the French-imposed empire was supported by the Roman Catholic clergy, many conservative elements of the upper class, and some indigenous communities. Conservatives and many in the Mexican nobility tried to revive the monarchy by bringing an archduke from the Royal House of Austria, Maximilian Ferdinand, or Maximilian I, to Mexico. France had various interests in this Mexican affair, such as seeking reconciliation with Austria, counterbalancing the growing American Protestant power by developing a powerful Catholic neighboring empire, and exploiting the rich mines in the northwest of the country.

Unbeknownst to the conservative elements of Mexican society, Maximilian was a liberal who wanted to reform Mexican government along the lines of Enlightenment philosophy. One of Maximilian’s first acts as Emperor was to restrict working hours and abolish child labor. He cancelled all debts over 10 pesos for peasants, restored communal property, and forbade all forms of corporal punishment. He favored the establishment of a limited monarchy that would share power with a democratically elected congress.

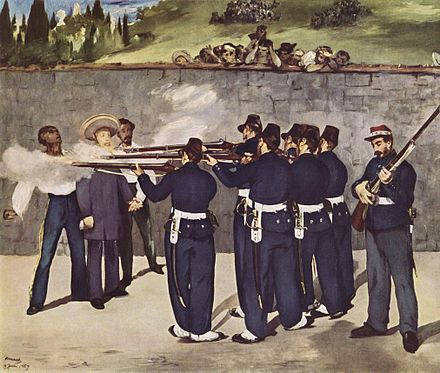

France never made a profit in Mexico and its Mexican expedition grew increasingly unpopular. Finally in the spring of 1865, after the US Civil War was over, the U.S. demanded the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. Napoleon III quietly complied. In mid-1867, despite repeated losses in battle to the Republican Army and ever-decreasing support from Napoleon III, Maximilian chose to remain in Mexico rather than return to Europe. He was captured and executed along with two Mexican supporters on June 19, 1867.

A painting by Edward Manet of the execution of Maximilian (Source: Wikimedia)

In the Caribbean, Cuba remained under the control of Spain for most of the 19th century, even as most of the remainder of the Spanish Empire broke away. Cuba had fifty-five steam engines by 1860 and was the largest exporter of sugar and richest colony in the world. The people however were displeased at the harsh treatment they received, and their anger erupted in 1895 with the brilliant poet Jose Marti becoming the chief spokesman for a new and stronger revolt.

Jamaica continued to have intermittent revolts against their British colonial rulers. When slavery was abolished in 1833, the sugar industry declined. Economic and social inequality generated tension and unrest, leading to riots.

The story of Haiti is somewhat involved. At the end of the last century Spain had ceded its part of the island, Santo Domingo, to France, but in 1801 the remarkable leader Toussaint Louverture conquered it. Although an expedition sent by Napoleon in 1802 failed to retake the island, Touissant was captured and died in a French prison. But Haiti remained independent. The eastern, Spanish part of the island never was fully assimilated and eventually out of the turmoil there emerged the Dominican Republic.