44 PACIFIC OCEANIA

AUSTRALIA

Although the first penal colonists, including 700 convicts and 324 officials and family members, landed in Botany Bay in 1788, the European population of Australia did not pass 50 thousand until 1830 and the 100 thousand mark was not reached until the late 1850s. As the 19th century began, Great Britain was so busy with Napoleon that there was little concern for Australia, and it was not until 1825 that even reasonable information was available about the New South Wales colony. Overall, by mid-century, 160,000 convicts had been sent, including many Irishmen.

A map of the Commonwealth of Australia (Source: Wikimedia)

Multiple attempts were made by the British to settle the northern tip of Australia, chiefly to harass the Dutch in the adjacent islands. By mid-century, all colonies had failed. In the south, wheat began to be of commercial importance by 1843, when a mechanical harvester called a “stripper” became available. Problems of land acquisition and ownership as well as the problem of labor supply continued for decades. Until 1850, free labor lived under the shadow of convict competition. In 1863, however, the political geography was fixed in the present-day pattern, although the Commonwealth did not materialize until 1901.

Gold in significant quantity was discovered in New South Wales and multiple areas of Victoria in the 1850s leading to massive immigration from Europe, America, and China. Australia’s population almost tripled from 1850 to 1860, reaching over one million people. Melbourne grew as the seat of government of the gold fields of Victoria, and the presence of thousands of “diggers” in those fields resulted in a lasting nickname for Australia’s residents.

Agriculture and especially sheep raising remained the mainstay of the economy. Farmers waged a continuous battle against sheep diseases, the carnivorous sheep-eating dingo ,and the pasture destroying kangaroos and imported rabbits throughout the 19th century. In Queensland in 1887 to 1889 some 3.7 million and 60 thousand dingoes were killed, but the rabbits remained uncontrolled. Wheat acreage was gradually increased during the century, with South Australia alone reaching over 1.5 million acres by 1891. Cane sugar became an important crop in Queensland by the end of the century. Less in true importance to the economy, but high in emotional value was mining – not only of the gold, but also of copper, a silver-lead-zinc complex, tin, and coal. The leading manufactured products were boots, shoes, and clothing.

Attempts to nationalize Australia and its various colonies surfaced at intervals after 1850 and culminated in 1891 when a constitutional convention was held in Sydney. On September 17, 1900, Queen Victoria signed a Proclamation to the effect that on and after the 1st day of January 1901, the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, Tasmania and Eastern Australia would be united in a federal commonwealth under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Australia’s remoteness from Euro-America lessened with the development of steam-driven ships and undersea cables. The appearance of refrigerated ships in the 1880s allowed shipment of frozen meat through the tropics to London markets. As a result, many farmers made fortunes. Urbanization progressed with Sydney reaching a population of 488 thousand in 1901 and Melbourne attaining 494 thousand in the same year. Immigration supplied over 25% of the increase in population in the last half of the century, with people from the British Isles leading the way. Next in number were Germans, with Italians a distant third. In the gold rush days, however, as we noted above, thousands of Chinese entered the area. The colony of Victoria legislated restriction on Chinese entry as early as 1855. Led by Sir Henry Parks, Victoria, South Australia, and Queensland all joined in passing fairly uniform legislation to stem the influx of Chinese workers. Western Australia followed in 1886 and Tasmania in 1887. By 1901, the Chinese population in Australia had shrunk to 32,000 from a high of about 50,000 in the 1870s.

In 1803, Great Britain took possession of the island of Tasmania and in the following year established a penal colony there. At that time there were approximately 7000 natives, but they were completely exterminated by 1888. Originally part of New South Wales, Tasmania became a separate colony in 1825, but did not receive its present name until 1853.

Four elderly Tasmanian Aborigines are pictured in this photograph taken in the early 1860s. The woman seated on the far right, Truganini, claimed to be the last of the Tasmanian people to survive. She died in 1876. (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch indigenous writer and anthropologist Bruce Pascoe discuss the “real history” of the aboriginal peoples of Australia in this fascinating TEDtalk. |

MELANESIA

European domination of the Pacific islands occurred slowly throughout the 19th century. New Caledonia, rich in minerals, became French in 1853 and by 1900 there were over twenty-three thousand Europeans living there. After 1887, New Hebrides was controlled by a joint naval commission of British and French officers.

New Guinea (Papua) is the world’s second largest island (Greenland is the largest). It was so named because of coastal similarity to Guinea in Africa and consists largely of tropical jungle. The west half of the island was annexed by the Dutch in 1828 and, in 1884, the British announced a protectorate over the southeast coast and adjacent islands, while the Germans claimed the northeast portion.

In Fiji, bordering Melanesia and Polynesia, Europeans came at the opening of the century looking for sandalwood. In a pattern repeated throughout the Americas and Asia, European diseases almost destroyed native Fijians, who were of Melanesian origin. The British annexed the islands in 1874. After the British took over, they hired natives to work in the cane fields, but at poor wages, and only a few were willing or able to do the work. As a result, the British began to import East Indian laborers.

Since whaling vessels stayed at sea until their barrels were filled with oil, the voyages sometimes took two or three years, and only the dregs and troublemakers of the sailing men’s world could be talked into signing up for such long voyages. As a result, the Pacific Islanders met many rough and dishonest American and British sailors who brought in rum, started fights, stole women, and anything else available. Some jumped ship to become pirates on their own, the most famous being “Bully” Hayes, who also was one of the originators of “blackbirding” (the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as laborers for little to no pay). Ship captains would “rent” natives to European businessmen to be used as laborers with the promise that after a certain period the “blackbird” would be released to return home. Few ever did. The men of Melanesia suffered most of this blackbirding and wherever they were taken, living condition were very bad, and many died of disease. In the late 1870s, the people of New Caledonia rebelled and began to defend themselves by whatever means available. The ensuing violence was noticed by European governments who finally forced an end to the traffic in island people.

MICRONESIA

The Japanese, feeling population pressure, began to move south in the Pacific, forcing the Chinese out of Okinawa and other Rykyu islands by 1875. They laid claim to the Bonins in 1861 and made them a part of their empire in 1876. They then soon took the three volcano islands of which Iwo Jima is one, and after the turn of the century they moved still further south into the true area of Micronesia.

POLYNESIA

In the 19th century, Americans, Russians, and Germans joined the Spanish, French, and English in extending political, military, and economic control over the regions of Oceania. In the first 50 years, European attention was given chiefly to the eastern islands, all of which, except Fiji, were inhabited by the Polynesian peoples. In the east Pacific as well as the west, Euro-Americans brought much grief to the island peoples, including disease and violence. Dysentery and childhood diseases, along with firearms, started the process of island depopulation. Whalers and missionaries, each in their own very opposite ways, had deleterious effects on the island natives.

In the 18th century, Captain Cook explored the Hawaiian Islands. In an effort to secure an agricultural base for Alaska, Georg Schaeffer, a Bavarian in the Russian Service, established forts at two places on Kauai in 1816, but was soon run out by American traders. At the time, the Hawaiian Islands functioned under their own government as constitutional monarchy led by Queen Liliuokalani. The Americans forcibly removed Queen Lili’uokalani in 1893 and claimed Hawaii as a territory of the United States.

A photograph of Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last independent monarch of Hawaii (Source: Wikimedia)

The Marquesas and Tahiti became French protectorates in 1842. At that time, the population of the Marquesas was about 20,000, but European diseases decimated the people, as elsewhere in the Pacific.

NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand, the only island group lying entirely within the temperate zone, is at the southwest corner of the great Polynesian triangle. Although discovered by Captain Cook in 1769, it had only temporary, various European settlements in the next half century. The British influence on the islands began in 1833 with the appointment of James Busby as a resident agent. In 1835, he signed the Treaty of Waitangi with Maori chieftains, forming an infant state of mixed whites and Maoris, under the “protection” of the Monarch of England. Legally this appeared to be a statement of intent to form a biracial society, with equal rights for both, but it survived only as an ideal. In spite of land wars which raged from time to time, New Zealand became a crown colony in 1842, with Captain William Hobson as the first governor. A constitution of 1852 set up a pseudo-federal system with 6 provinces, each with legislatures and central governments, but the Maori were denied political rights because they were not landowners individually, as the Europeans were, but communally. Although not represented, they were still heavily taxed. Hobson and his successors had great difficulties pleasing both the Maori chieftains and the white settlers. European New Zealand reached political stability under the leadership of a liberal prime minister, Richard John Seddon (1893-1906) and the help of rising prices and the export of meat, cheese, and butter facilitated by refrigerated shipping.

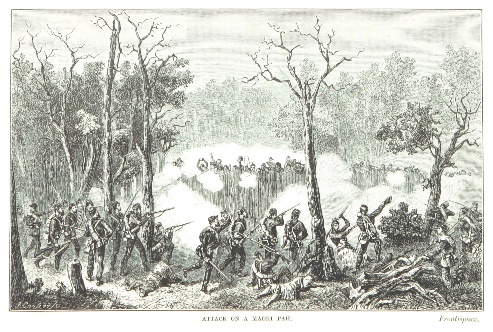

A drawing of an attack on the Maori by English forces by James Alexander, 1873 (Source: Wikimedia)

The principal promoter of systematic settlement, the New Zealand Company, was motivated by land hunger at the expense of those whom they called “naked savages,” and the racial situation rapidly deteriorated. The conflict led to the New Zealand Wars which lasted from March 1860 to February 1872. The result of the conflict was the lessening of power for the Maoris and the expansion of European settlements. Maori suffered greatly from the white man’s diseases, including venereal ones, changes in diet and clothing and the violence of European weapons. By 1840, the indigenous Maori had declined from a previous high population of perhaps 200,000 down to about 100,000 in the North Island. By 1896, there were only 42,000 Maori left.