28 THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

The decline of the Mughal Empire began shortly after the death of its sixth emperor, Aurangzeb, in 1707. Internal divisions and external pressures weakened the empire, making it vulnerable to invasions. One major invasion was led by Nadir Shah, the Persian ruler, who invaded Delhi in 1739, causing substantial destruction and further undermining Mughal authority.

As the Mughal Empire weakened, regional powers began to rise. The Sikhs gained autonomy in the Punjab region (northwestern India, near the border with Pakistan) and established their own military confederacies, known as misls. These misls controlled various areas and played a crucial role in the formation of the Sikh Empire, which was later consolidated by Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839). Meanwhile, Ahmad Shah Durrani (1722–1772), the founder of modern Afghanistan, led several invasions into northern India, but his impact on Mughal territories was transient.

A portrait of Ahmad Shah Durrani (Source: Wikimedia)

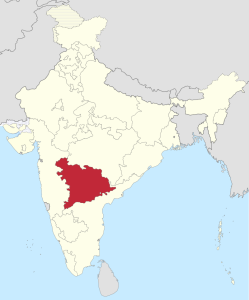

In the eastern Deccan region (a large plateau in southern India), the Nizam of Hyderabad emerged as a significant political and military ruler in the early 18th century. The title “Nizam” referred to the viceroy appointed by the Mughal emperor to govern the Deccan region. However, as Mughal authority weakened, the Nizam, initially Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I, declared autonomy, establishing the Asaf Jahi dynasty, which ruled Hyderabad from the 1720s. The Nizam’s territory extended over much of present-day Telangana, parts of Maharashtra, and Karnataka.

The city of Hyderabad grew into a flourishing cultural hub known for its architecture and a vibrant court life that attracted poets, musicians, and scholars. The Nizam promoted the arts, education, and trade, with Hyderabad becoming an important economic center. Despite these developments, rural areas faced challenges due to heavy taxation, land disputes, and occasional conflicts with neighboring states. Nonetheless, the region remained a significant player in South Indian politics and continued to exert influence long after the decline of Mughal authority.

For ordinary people in Hyderabad, daily life was deeply intertwined with religion, family, and economic realities. Most residents practiced Islam or Hinduism, with religious festivals and rituals playing a central role in community life. Women’s roles were largely confined to domestic duties, although some upper-class women received education and participated in cultural pursuits. Family ties were strong, with extended families often living together. Economically, the majority of the population engaged in agriculture, craftsmanship, or trade, struggling with heavy taxation, limited social mobility, and precarious livelihoods. In rural areas, farmers toiled on land owned by absentee landlords, while artisans and traders navigated complex networks of patronage and credit. Despite these challenges, Hyderabad’s bustling markets and vibrant cultural scene offered glimpses of prosperity and hope for a better life.

In the western Deccan region, the Kingdom of Mysore, founded by Yaduraya Wodeyar in 1399, experienced significant growth and transformation during the 18th century. Under Narasaraja Wodeyar II (1704-1714), Mysore consolidated its power and resisted invasions from neighboring kingdoms. Haidar Ali (1761-1782), a skilled military leader and administrator, modernized the army, expanded territories, and established a robust economy. His reign saw the development of Mysore’s agricultural sector, trade networks, and cultural institutions. Tipu Sultan (1782-1799) continued this legacy, fostering alliances with neighboring kingdoms and the Ottoman Empire, while implementing innovative administrative and economic reforms.

Tipu Sultan: A Paradigm of Intercultural Competency

Sultan Tipu Sultan, the 18th-century ruler of Mysore, exemplifies intercultural competency through his diplomatic, administrative, and cultural efforts. His interactions with French, British, and Ottoman dignitaries illustrate his skill in navigating diverse cultural contexts. Tipu Sultan employed French military experts, such as Louis Xavier Duprat, to modernize his army and maintained strong ties with the Ottoman Empire through diplomatic missions. He also integrated Islamic, Hindu, and European architectural styles in his palaces and mosques, reflecting his appreciation for cultural diversity. Additionally, his administrative reforms, including the adoption of Persian as an official language, show his openness to different cultural practices. His correspondence with the French Revolution’s National Assembly, expressing solidarity and admiration, demonstrates his engagement with Enlightenment ideals. Tipu Sultan’s intercultural competency enabled effective governance, strategic alliances, and cultural exchange, solidifying his legacy as a visionary leader.

The 18th century also saw remarkable cultural and economic activity across India. The Bengal region (located in eastern India, encompassing parts of present-day Bangladesh and West Bengal) was known for its rich cultural contributions, including developments in literature and arts. Bengali literature flourished with poets like Kazi Nazrul Islam and the proliferation of regional theater and music. The Mughal artistic traditions continued to influence local art and architecture, with notable examples of intricate craftsmanship and artistic patronage.

The Maratha Empire (a confederation of states in western India, centered around Maharashtra) emerged as a significant political force in the 18th century. Founded by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in the late 17th century, the Marathas established a vibrant and diverse administration that promoted economic development, trade, and cultural patronage. The Maratha Confederacy, a coalition of various Maratha chieftains, played a crucial role in resisting both Mughal and foreign invasions, contributing to the stability and prosperity of the region.

In the 18th century, India’s scientific community continued to thrive, building on its rich heritage of innovation across various disciplines. Indian scholars were at the forefront of significant advancements in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and metallurgy. They carried forward a tradition of rigorous intellectual pursuit that had been established centuries earlier.

One of the notable figures of this period was Jagannatha Samrat (1690–1750), a distinguished mathematician and astronomer. His seminal work, “Rekhaganita” (Linear Mathematics), made substantial contributions to the field of mathematics, particularly in the study of linear equations and geometric principles. Samrat’s works were influential not only in India but also in the broader scientific community, demonstrating the depth and sophistication of Indian mathematical scholarship during this era. Another key figure was Shankara Varman (1730–1800), who was renowned for his contributions to mathematical theory. Varman authored several important mathematical treatises, which expanded on previous knowledge and introduced new concepts and methods. His works reflected the ongoing evolution of mathematical thought in India, showcasing a blend of traditional methods and innovative approaches.

In the realm of medicine, Indian physicians such as Sakat Singh Chawarne (1740–1820) and Todar Mal (1750–1830) were instrumental in advancing medical practices. They developed new treatments by integrating traditional Ayurvedic practices with emerging European medical knowledge. Ayurveda, an ancient Indian system of medicine, emphasizes natural remedies, herbal treatments, and holistic wellness. The fusion of Ayurvedic techniques with European approaches allowed for more comprehensive and effective medical treatments, illustrating a dynamic exchange of knowledge between different medical traditions.

The Jantar Mantar observatories, established by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II of Jaipur (1699–1743), were significant in the field of astronomy. These observatories, located in Jaipur, Delhi, and other cities, were equipped with advanced instruments designed to track celestial movements and predict astronomical events. The observatories enabled Indian scholars to make precise predictions about eclipses and planetary alignments, demonstrating the advanced state of Indian astronomical research. The meticulous observations and calculations conducted at these sites contributed to a deeper understanding of celestial phenomena and reinforced India’s role in the global scientific community.

Overall, the 18th century was a period of remarkable scientific and intellectual activity in India. The contributions of Indian scholars and practitioners during this time not only advanced various fields of study but also exemplified the synthesis of traditional knowledge with new insights. This period highlighted the vibrant and evolving nature of Indian science and its impact on the global stage.

A drawing of ships in the Surat harbor at the beginning of the 18th century (Source: Wikimedia)

During the mid-18th century, the British East India Company’s expanding presence in India marked the beginning of a new era of colonial rule. Following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the British Indian Empire grew rapidly, with tens of thousands of British officials, soldiers, and traders arriving in India by the late 18th century. This influx had far-reaching consequences for India’s economy, politics, and society as the East India Company’s dominance led to economic exploitation, with Indian farmers forced to pay hefty taxes, often up to 50% of their produce. This enrichment of British fortunes came at the cost of widespread poverty and economic hardship for millions of Indians. As British control expanded, English began to play an increasingly prominent role in administration, commerce, and education, reflecting the growing influence of the British in India. By the end of the century, the number of English speakers had risen dramatically, with thousands of British officials, soldiers, and traders integrating English into the fabric of colonial rule.