39 THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

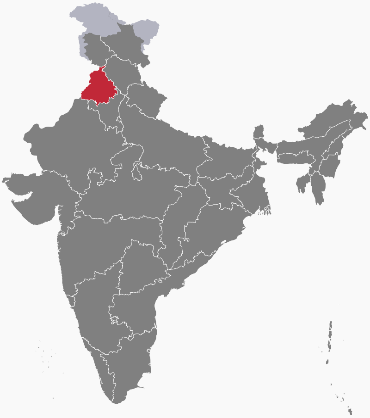

Indian history in the 19th century is a complex story of British imperialism and Indian resistance. Some regions were annexed outright by the British while others were brought under control through a system of subsidiary alliances. Some regions of India deserve special attention. The Punjab in northwest India was called the “country of five rivers.” It had been ruled through the centuries by Persians, Macedonians, Scythians, Parthians, Huns, and then the Mughals. The Punjab was the granary of India, a feat made possible by an immense network of irrigation canals. In the 19th century, approximately fifteen million Hindus, sixteen thousand Muslims, and five million Sikhs lived and worked there. Thirty-five million Muslims and thirty million Hindus lived in the state of Bengal at the mouth of the Ganges in 1800. In spite of the religious divisions, all Bengali spoke the same language. Muslims lived in the eastern region while Hindus inhabited the west.

This map shows the location of the Punjab region in the Indian peninsula (Source: Wikimedia)

The Marathas were crushed by the British in 1818 and all prospects of a powerful independent Indian state and culture disappeared. The use of legislation to institute social change began during the governor-generalship of Lord William Bentinck (1828-1835). Changes included support of higher education institutions that used the English language. This was seen as a means of introducing a true understanding of the world.

By applying both military and economic pressure, the British gradually assumed control of the entire region. The East India Company, which had been in the foreground of imperialism, was terminated by royal decree on August 12, 1858 and the British monarch, Queen Victoria, took over direct control of India. Ultimately, two thousand members of the Indian Civil Service and ten thousand British officers had authority over the three-hundred million Indian people.

Famine occurred through most of India in 1866 and again in 1877 and then periodically until 1899, although commercial agriculture flourished. When another episode of plague arrived in Bombay in 1898, within ten years, six million people died. The first all Indian political organization was founded in 1885 as the Indian National Congress. This organization dominated Indian political and social thinking in the next century.

At the end of the 19th century, India was the second largest nation on earth with about five times as many Hindus as Muslims, several million Sikhs, and a small population of Christians, Parsees, and Jews. There were 15 official languages and 845 dialects. Cholera was endemic but became general and violent throughout this century and even spread to Europe. A virulent form of tuberculosis developed in the previous century and continued to ravage in the 19th. More than three million Indians migrated to other countries along the shores of the Indian Ocean and throughout the British commonwealth. After the 1830s, there was a large migration of Indian Tamils to Sri Lanka to labor on the coffee, tea, and rubber plantations. They joined other Tamils whose ancestors had arrived centuries before from the south of India. Most practiced Hinduism, in contrast to the majority Sinhalese of the island, who were Buddhists.

The British presence in India provoked different reactions. Some Indians willingly cooperated with the colonial authority to their own advantage. Many found employment, status, and security by enlisting in the English army. Others became part of the administrative structure of the British empire by serving as lower-level clerks and bureaucrats. A few received higher education in Britain and returned home as lawyers, engineers, and doctors. The English government relied heavily on cooperating Indians to govern its massive imperial enterprise.

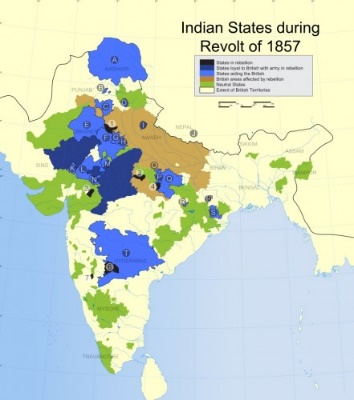

However, many Indians rejected the British presence and did all that they could to oppose it. The most organized of the attempts to overthrow the British in the 19th century occurred in 1857. This revolt was triggered by the introduction of a new cartridge smeared with animal fat from cows and pigs into the colony’s military forces. Because Hindus venerated cows and Muslims regarded pigs as unclean, both groups were repulsed and deeply offended. The anger of the local population at the British colonial presence boiled over as local rulers who had lost power, landlords who had been deprived of their estates, and peasants who were overtaxed and underpaid joined forces in a rebellion against British authority. Although the British crushed the rebellion within a year, the rebellion widened the racial divide in colonial India and convinced the British that the Indians could not be trusted.

This map shows the states in India that joined the Rebellion in 1857 (Source: Wikimedia)

|

Watch and Learn |

|

This short, animated video, How did Britain Conquer India?, reviews the history of British Imperialism in India and explains the methods used by the British to subdue and control the Indian people. |