48 WORLD WAR II

The First World War devastated Europe with millions of casualties and the destruction of land and property. A slow process of economic recovery began in the years following the war. Any such recovery, however, was short-lived, as European economies suffered under the depression of the 1930s.

The 1920s: Reparations, Inflation, and Weak Recovery

The peace treaties signed to end the First World War included harsh economic penalties for the Central Power aggressors. Reparation payments forced the Central Powers to assume financial responsibility for the damage caused during the war. In 1921, the Inter-Allied Reparations Committee determined that Germany should pay 269 billion marks, or approximately 100,000 tons of pure gold. This sum was later reduced to 132 billion marks. Germany was unable to follow the schedule of payments. Its treasury was emptied of all precious metals to pay the debt, which then devalued the currency completely. The German government printed large amounts of currency causing a state of hyperinflation. For example, a cup of coffee cost 14,000 marks. At the peak of inflation, the rate of exchange was one trillion marks to one dollar.

While European countries entered a period of economic growth from about 1925 to 1929, the gains they made were modest. Unemployment was still high, and the benefits of growth were unevenly shared. The gap between rich and poor increased, a situation that was exacerbated by a rise in the general population. Most people, therefore, had not improved their financial situation much when depression hit in the 1930s.

The Great Depression

Much of Europe’s survival and prosperity in the 1920s relied on American loans. When the U.S. stock market crashed in October 1929, American credit disappeared, which drastically affected European businesses. In Germany, where the recovery had been particularly weak, the depression hit particularly hard. Six million Germans were unemployed in the early 1930s. In 1931, when the German and Austrian economies seemed in danger of collapse, the United States brokered a deal to place a moratorium on reparations payments. The deal did not do much to help either country’s economy, but it hurt other European countries instead. The British, who relied partly on German reparations payments to make their own repayments to the U.S., suffered a near-collapse of their financial system.

European governments also responded poorly to the onset of depression. The British, who relied heavily on external trade, raised tariffs, and abandoned free trade in general. The French, meanwhile, reduced the civil service as well as payments to former members of the military. Both actions – raising tariffs and thereby discouraging trade and reducing the civil service and thereby destroying jobs – have since been determined to have deepened the Great Depression. The difficulty was that governments across Europe followed the same pattern in dealing with the Depression. The continent therefore remained mired in depression for the rest of the decade.

Fascist Economies

In the wake of the economic downturn of the 1930s, a more authoritarian form of political governance increasingly appealed to Europeans. While fascist political parties gained adherents throughout Europe, in Germany, the National Socialists, or Nazis, a fascist party, succeeded in obtaining power. Fascism was based on the idea that the masses should participate directly in the state, not through a legislative body such as a parliament, but through a fusion of the population into one “spirit.” The individual was insignificant, and the nation-state was the supreme embodiment of the destiny of its people. The fascist government controlled every aspect of the lives of its citizens. The ideals of economic stability and social peace could be obtained only through dictatorship and tight control over the press, education, police, and the judicial system. Fascists had enjoyed political success before the Nazi seizure of power in 1932-33. In the 1920s, Benito Mussolini’s fascist movement gained control in Italy with much popular support. By 1929, as the Great Depression loomed, there was a new sense of order in the Italian economy and society. Mussolini’s popular support, however, plummeted after he failed to implement effective social change in the 1930s.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about Fascism in Europe by watching the Khan Academy’s video: Fascism and Mussolini

|

The 1930s witnessed the rise of fascist control in Germany. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, the Nazis implemented a major state-directed economic plan aimed at jump-starting the economy. Hjalmar Schacht, a former German Democratic Party member, created the plan. Schacht introduced price controls and borrowed heavily to finance large public-works projects. Rearmament was a major component of Schacht’s plan, but there were also major projects, such as the construction of the Autobahn and production of the Volkswagen. These projects were moderately successful in creating growth and also reduced unemployment significantly. The economic success of the Nazis was one of the reasons that the Nazis won respect from many people in Depression-ridden Europe. It also solidified the support and loyalty of the German people.

In 1936, Hitler replaced Schacht with Hermann Göring. Göring was ordered to make the German army ready for war in four years, even though specific provisions in the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from rearming after World War I. The military build-up that followed stimulated the German economy tremendously. German industry enlisted in the Nazi economy as well, and the country increased in prosperity as well as self-confidence, in marked contrast to democratic Europe.

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Learn more about the rise of Hitler and Nazism by watching the Khan Academy’s video: Initial Rise of Hitler and the Nazis

|

The Communist Economy

To the depressed economies of Europe in the 1930s, Communist Russia’s economy also seemed like a major success story. By the beginning of the 1920s, Russia’s economy was ruined because of the First World War and several years of civil war. Industrial production dropped to 18% of prewar levels, agriculture was less than half of prewar levels, and unemployment was rampant. Years of war, famine, and disease left many orphans wandering city streets. Robbery by packs of little children was an ordinary fact of life.

It was difficult for the Bolsheviks to digest the fact that the international Communist revolution had not materialized. After a great deal of hesitation, they declared that Russia had entered a transitional stage on the route to Communism. Marx had spoken about such a stage, but he indicated that it would not last long. As a result, the Bolsheviks announced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. Under the NEP, the state stopped confiscating businesses (which it had done during the civil war), the market was opened (though to small business only), and currency was restored. The government maintained its monopoly in heavy industry and the major means of production. Thus, from 1921 to 1928, a market economy existed in Russia.

The NEP pleased the peasants, who finally brought their grain to market. The peasant revolts stopped. The economy revived immediately and the living standards of both workers and peasants improved. Food rations were no longer necessary, and the famine was over. Though the NEP seemed like a good policy, it was problematic for the Bolsheviks. They had viewed its passage as a necessary step backward on the road to a Communist paradise, and eventually they would have to move forward. The NEP set the stage for an unequal distribution of wealth and also foreshadowed one of the great problems the Communists would face. Marx had theorized that workers would overproduce when they owned the means of production, but they didn’t.

When Joseph Stalin came to power in the second half of the 1920s, he therefore began to move the USSR away from the NEP. His new policies involved large-scale industrialization and collectivization. Stalin realized that Russia had been crushed in the First World War because its industry was not developed enough and claimed that Russia was 50 to 100 years less industrialized than the Western powers. To survive the coming assault, they needed to be ready in ten years.

An official photograph of Joseph Stalin (Source: Wikimedia)

Industrial output quadrupled within ten years. Workers toiled with tremendous enthusiasm, thanks to propaganda promising that their rewards were only a few years away. The Communists began a number of enormous projects that could only have been completed with the help of the workers. They also succeeded in electrifying the entire region. The Soviets produced their own tractors at an astonishing rate; they made the best tanks in the world in incredible numbers; they created their own aircraft industry, and the Soviet air force was equal to the Luftwaffe by the outset of the Second World War.

Agricultural collectivization, however, proved less successful than industrialization. Collectivization had both economic and political aims. It enabled the government to make agriculture into an industrial enterprise, which would theoretically produce more because of economies of scale. By creating collective farms, the Communists hoped to eliminate the peasant class and replace it with a rural working class.

Though in theory all Soviets owned the collective farms together, in practice the government administered them. The government had a plan for how much each farm should produce. It would take a quota that amounted to at least the majority of that production and divide anything that was left among the farmers. The farmers could either consume the surplus, or they could sell it on the open market. In practice, many collective farms produced less than the small farms had. The government had to meet the planned quota, so it took everything from the less productive farms. The peasants who worked these farms essentially worked for free and had to depend on their own land to survive. As a result, the 1930s was a period of terrible starvation across the USSR, though these tales rarely reached Western audiences.

|

Watch and Learn & Click and Explore |

|

Learn about World War II by watching Crash Course in World History #38

|

|

To review the major events of the Second World War, look carefully at this Timeline of Key Dates produced by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. |

The War in Europe

In the early stages of World War II, Nazi Germany successfully invaded its neighbors aided by the air power of the German Airforce, known as the Luftwaffe, which was able to establish tactical air superiority with great efficiency. Slowly at first, and then with more aggression, the Nazis pursued territorial expansion by annexing Austria and the German-speaking provinces of Czechoslovakia. Germany followed this up, on September 1, 1939, by invading Poland. In response, both Great Britain and France declared war on German. Germany responded by invading Belgium and then France, unleashing a ruthless air campaign against Great Britain, and finally invading the Soviet Union in 1941.

The Blitz

The Blitz, from the German word “Blitzkrieg” (lightning war) was the name borrowed by the British press and applied to the heavy and frequent bombing raids carried out over Britain in 1940 and 1941. This concentrated, direct bombing of industrial targets and civilian centers began with heavy raids on London on September 7, 1940, during the Battle of Britain.

Office workers in London walk through debris after a heavy air raid (Source: Wikimedia)

London was systematically bombed by the Luftwaffe for 57 consecutive nights. More than one million London houses were destroyed or damaged and more than 40,000 civilians were killed, almost half of them in London. Ports and industrial centers outside London were also attacked. The main Atlantic Sea port of Liverpool was bombed, causing nearly 4,000 deaths within the Merseyside area during the war. The North Sea port of Hull, a convenient and easily found target or secondary target for bombers unable to locate their primary targets, was subjected to 86 raids in the Hull Blitz during the war, with a conservative estimate of 1,200 civilians killed and 95 percent of its housing stock destroyed or damaged. Other ports, including Bristol, Cardiff, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton, and Swansea, were also bombed, as were the industrial cities of Birmingham, Belfast, Coventry, Glasgow, Manchester, and Sheffield. Birmingham and Coventry were chosen because of the Spitfire and tank factories in Birmingham and the many munitions’ factories in Coventry. The city center of Coventry was almost destroyed, as was Coventry Cathedral.

The bombing failed to demoralize the British into surrender or significantly damage the war economy. The eight months of bombing never seriously hampered British production and the war industries continued to operate and expand. By May 1941, Hitler and the Nazi’s abandoned the idea of invading Great Britain and instead turned their attention to Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for the Nazi attack. The operation was driven by Adolf Hitler’s ideological desire to destroy the Soviet Union as outlined in his 1925 manifesto Mein Kampf. The actual invasion began on June 22, 1941. Over the course of the operation, about four million German soldiers invaded the Soviet Union along a 1,800-mile front, the largest invasion force in the history of warfare. In addition to troops, the Germans employed approximately 600,000 motor vehicles and between 600,000 and 700,000 horses. It transformed the perception of the Soviet Union from aggressor to victim and marked the beginning of the rapid escalation of the war, both geographically and in the formation of the Allied coalition. The Nazi army won resounding victories and occupied some of the most important economic areas of the Soviet Union, mainly in Ukraine, both inflicting and sustaining heavy casualties. Despite their successes, however, the German offensive stalled on the outskirts of Moscow and was subsequently pushed back by a Soviet counteroffensive.

Significance

Operation Barbarossa was the largest military operation in human history—more men, tanks, guns, and aircraft were committed than had ever been deployed before in a single offensive. Seventy-five percent of the entire German military participated. The invasion opened up the Eastern Front of World War II, the largest theater of war during that conflict, which witnessed titanic clashes of unprecedented violence and destruction for four years that resulted in the deaths of more than 26 million people. More people died fighting on the Eastern Front than in all other fighting across the globe during World War II. Damage to both the economy and landscape was enormous for the Soviets as approximately 1,710 towns and 70,000 villages were completely annihilated.

More than just ushering in untold death and devastation, Operation Barbarossa and the subsequent German failure to achieve their objectives changed the political landscape of Europe, dividing it into eastern and western blocs. The gaping political vacuum left in the eastern half of the continent was filled by the Soviet Union when Stalin secured firmly placed his Red Army in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the eastern half of Germany at the end of the War.

The Holocaust

The Holocaust was a genocide in which Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany and its collaborators killed approximately six million Jews. The victims included 1.5 million children and represented about two-thirds of the nine million Jews who resided in Europe. Killings took place throughout Nazi Germany, German-occupied territories, and territories held by allies of Nazi Germany.

From 1941 to 1945, Jews were systematically murdered in the deadliest genocide in human history. Under the coordination of the SS and direction from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, every arm of Germany’s bureaucracy was involved in the logistics and administration of the genocide. Other victims of Nazi crimes included ethnic Poles, Soviet citizens and Soviet POWs, other Slavs, Romanis, communists, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the mentally and physically disabled. A network of about 42,500 facilities in Germany and German-occupied territories was used to concentrate victims for slave labor, mass murder, and other human rights abuses. Over 200,000 people were Holocaust perpetrators.

A photograph of Hungarian Jews being selected by Nazis to be sent to the gas chamber at Auschwitz concentration camp. (Source: Wikimedia)

The persecution and genocide were carried out in stages, culminating in what Nazis termed the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question,” an agenda to exterminate Jews in Europe. Initially, the German government passed laws to exclude Jews from civil society, most prominently the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. Nazis established a network of concentration camps starting in 1933 and ghettos following the outbreak of World War II in 1939. In 1938, legal repression and resettlement turned to violence on Kristallnacht (“Night of Broken Glass”), when Jews were attacked, and Jewish property was vandalized. Over 7,000 Jewish shops and more than 1,200 synagogues (roughly two-thirds of the synagogues in areas under German control) were damaged or destroyed. In 1941, as Germany conquered new territory in eastern Europe, specialized paramilitary units called Einsatzgruppen (“death squads”) murdered around two million Jews, partisans, and others, often in mass shootings. By the end of 1942, victims were regularly transported by freight trains to extermination camps where most who survived the journey were systematically killed in gas chambers. The use of extermination camps (also called “death camps”) equipped with gas chambers for the systematic mass extermination of peoples was an unprecedented feature of the Holocaust. These were established at Auschwitz, Belzec, Chełmno, Jasenovac, Majdanek, Maly Trostenets, Sobibór, and Treblinka. They were built for the systematic killing of millions, primarily by gassing but also by execution and extreme work under starvation conditions. This continued until the end of World War II in Europe in April–May 1945.

D-Day: The Normandy Landings

On Tuesday, June 6, 1944, (termed D-Day) the combined forces of the United States and Great Britain invaded Normandy in Operation Overlord. The largest seaborne invasion in history, the operation began the liberation of German-occupied northwestern Europe from Nazi control. The amphibious landings were preceded by extensive aerial and naval bombardment and an airborne assault—the landing of 24,000 American, British, and Canadian airborne troops shortly after midnight. Allied infantry and armored divisions began landing on the coast of France at 06:30. The men landed under heavy fire from gun emplacements overlooking the beaches, and the shore was mined and covered with obstacles such as wooden stakes, metal tripods, and barbed wire, making the work of the beach-clearing teams difficult and dangerous. German casualties on D-Day have been estimated at 4,000 to 9,000 men. Allied casualties were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead. These landings proved to be critical in the ultimate victory of the Allied forces who continued to march through Europe to the ultimate capture of Berlin and the subsequent German unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945.

Liberation of Concentration Camps

As the Allies advanced on Germany, they began to discover the extent of the Holocaust. The first major camp to be encountered, Majdanek, was discovered by the Soviet armed forces on July 23, 1944. Chełmno was liberated by the Soviets on January 20, 1945. Auschwitz was liberated, also by the Soviets, on January 27, 1945; Buchenwald by the Americans on April 11; Bergen-Belsen by the British on April 15; Dachau by the Americans on April 29; Ravensbrück by the Soviets on the same day; Mauthausen by the Americans on May 5; and Theresienstadt by the Soviets on May 8. Treblinka, Sobibór, and Bełżec were never liberated, but were destroyed by the Nazis in 1943. In most of the camps discovered by the Soviets, almost all the prisoners had already been removed, leaving only a few thousand alive—7,600 inmates were found in Auschwitz, including 180 children who had been experimented on by doctors. Almost 60,000 prisoners were discovered at Bergen-Belsen by the British 11th Armored Division, 13,000 corpses lay unburied, and another 10,000 died from typhus or malnutrition over the following weeks.

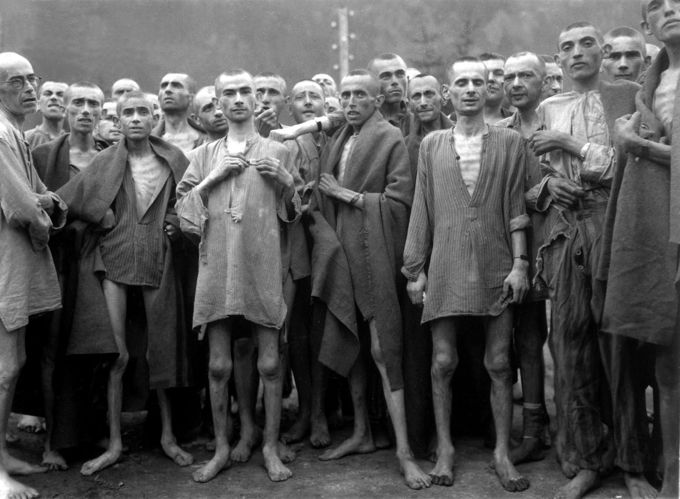

A photograph of starving prisoners in a concentration camp liberated on May 5, 1945 (Source: Wikimedia)

The War in the Pacific

The roots of World War II in Asia are found in the military expansion of Japan in the 1930s who seized control of Manchuria in 1931 and invaded China in 1937. In 1940-41, Japan extended its military operations throughout Southeast Asia in an attempt to acquire access to natural resources that would eliminate its need to acquire these from the United States and Europe. The final step in the development of World War II in the Pacific was Japan’s decision to attack the US military based at Pearl Harbor (Hawaii) on December 7, 1941.

The attack came as a profound shock to the American people and led directly to the American entry into World War II in both the Pacific and European theaters. The day after the attack, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt called for a formal declaration of war on the Empire of Japan. Congress obliged his request less than an hour later. On December 11, Germany and Italy joined Japan and declared war on the United States. The Axis powers of Japan, Germany, and Italy were united against the Allied powers of the United States, Great Britain, and Russia.

The Battle of Midway and the Guadalcanal Campaign

The Battle of Midway was a decisive naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II, won by the American navy after codebreakers discovered the date and time of the Japanese attack. Between June 4 and 7, 1942, only six months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea, the United States Navy under Admirals Chester Nimitz, Frank Jack Fletcher, and Raymond A. Spruance decisively defeated an attacking fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy under Admirals Isoroku Yamamoto, Chuichi Nagumo, and Nobutake Kondo near Midway Atoll, inflicting devastating damage on the Japanese fleet that proved irreparable.

The Guadalcanal campaign marked the decisive Allied transition from defensive operations to the strategic initiative in the Pacific theater, leading to offensive operations such as the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Central Pacific campaigns that eventually resulted in Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II. This military campaign was fought between August 7, 1942, and February 9, 1943, on and around the island of Guadalcanal in the Pacific theater of World War II. It was the first major offensive by Allied forces against the Empire of Japan and thus a significant strategic combined arms Allied victory in the Pacific theater. Along with the Battle of Midway, it has been called a turning-point in the war against Japan. The victories at Milne Bay, Buna-Gona, and Guadalcanal marked the Allied transition from defensive operations to strategic initiative, leading to offensive operations such as the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and Central Pacific campaigns that eventually resulted in Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II.

Island Hopping

Leapfrogging, also known as island hopping, was a military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against Japan and the Axis powers during World War II. The idea was to bypass heavily fortified Japanese positions and instead concentrate the limited Allied resources on strategically important islands that were not well-defended but were capable of supporting the drive to the main islands of Japan. This strategy was possible in part because the Allies used submarine and air attacks to blockade and isolate Japanese bases, weakening their garrisons and reducing the Japanese ability to resupply and reinforce them. Leapfrogging had a number of advantages. It allowed the United States forces to reach Japan quickly and not expend the time, manpower, and supplies to capture every Japanese-held island on the way. It gave the Allies the advantage of surprise and kept the Japanese off balance.

The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

In the final year of the war, the Allies prepared for what was anticipated to be a very costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. This was preceded by a U.S. firebombing campaign that destroyed 67 Japanese cities. The war in Europe concluded when Nazi Germany signed its instrument of surrender on May 8, 1945. The Japanese, facing the same fate, refused to accept the Allies’ demands for unconditional surrender and the Pacific War continued. Together with the Great Britain and China, the United States called for the unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945—the alternative being “prompt and utter destruction.” The Japanese responded to this ultimatum by ignoring it.

In response, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in the first nuclear attack in history. Three days later, on August 9, the U.S. dropped another atomic bomb on Nagasaki, the last nuclear attack in history. The two bombings, which killed at least 129,000 people, remain the only use of nuclear weapons for warfare in history. Within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000–146,000 people in Hiroshima and 39,000–80,000 in Nagasaki; roughly half of the deaths in each city occurred on the first day. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison. On August 15, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war, Japan announced its surrender to the Allies. On September 2, it signed the instrument of surrender, effectively ending World War II.

The role of the bombings in Japan’s surrender and the U.S.’s ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. Supporters of the bombings generally assert that they caused the Japanese surrender, preventing casualties on both sides during Operation Downfall. Those who oppose the bombings cite a number of reasons, including the belief that atomic bombing is fundamentally immoral, that the bombings counted as war crimes, that they were militarily unnecessary, that they constituted state terrorism, and that they involved racism against and the dehumanization of the Japanese people.

The End of the War

The German Instrument of Surrender that ended World War II in Europe was signed on May 8, 1945. The surrender of Japan was announced by Imperial Japan on August 15 and formally signed on September 2, 1945, bringing the hostilities of World War II to a close.

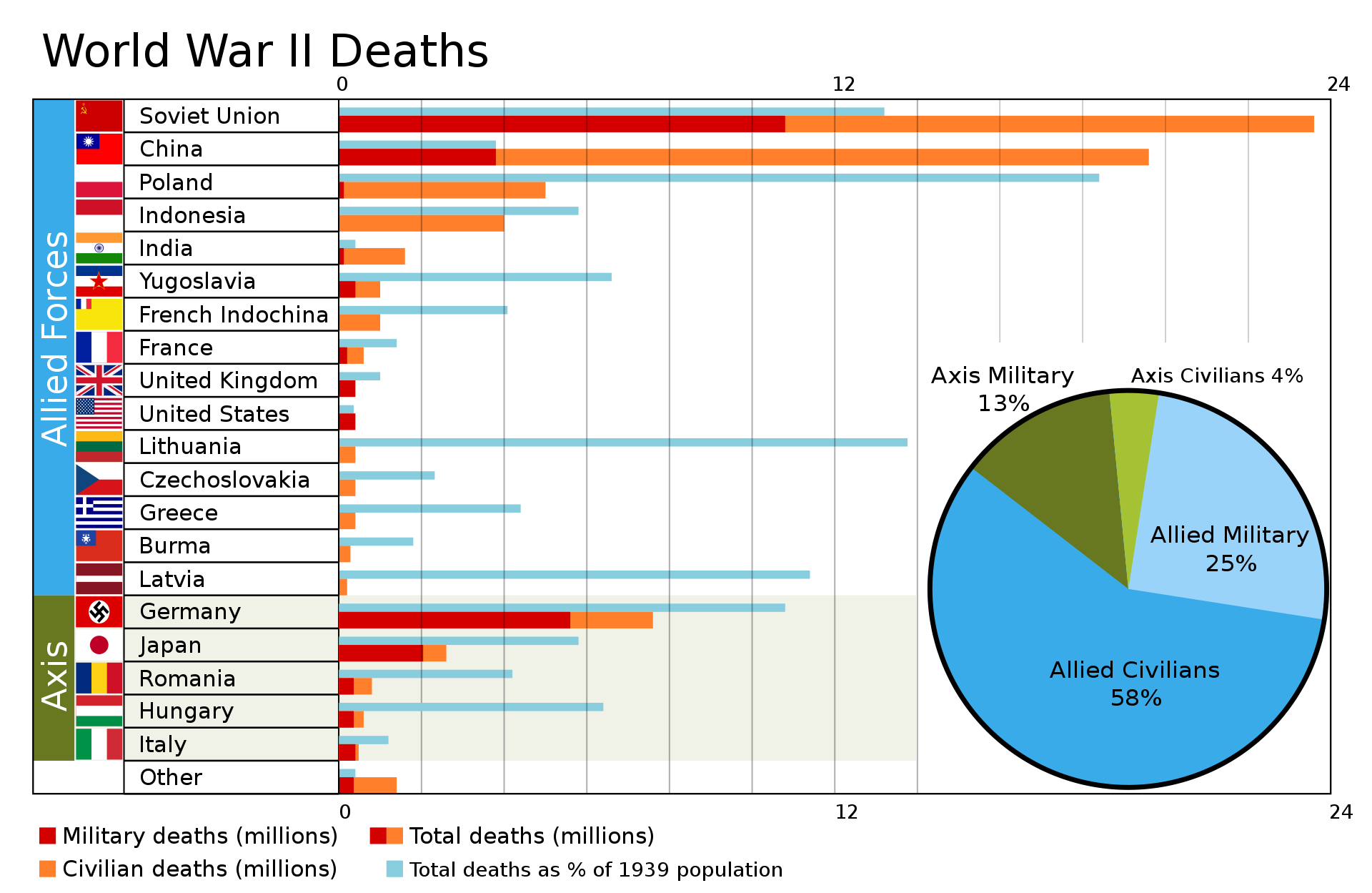

Casualties of World War II

Close to 75 million people died in World War II, including about 20 million military personnel and 40 million civilians, many of whom died because of deliberate genocide, massacres, mass-bombings, disease, and starvation. The Soviet Union lost around 27 million people during the war, including 8.7 million military and 19 million civilian deaths. The largest portion of military dead were 5.7 million ethnic Russians, followed by 1.3 million ethnic Ukrainians. A quarter of the people in the Soviet Union were wounded or killed. Germany sustained 5.3 million military losses, mostly on the Eastern Front and during the final battles in Germany.

Of the total number of deaths in World War II, approximately 85 percent—mostly Soviet and Chinese—were on the Allied side and 15 percent on the Axis side. Many deaths were caused by war crimes committed by German and Japanese forces in occupied territories. An estimated 11 to 17 million civilians died either as a direct or as an indirect result of Nazi ideological policies, including the systematic genocide of around 6 million Jews during the Holocaust and an additional 5 to 6 million ethnic Poles and other Slavs (including Ukrainians and Belarusians), Roma, homosexuals, and other ethnic and minority groups. Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Serbs, along with gypsies and Jews, were murdered by the Axis-aligned Croatian Ustaše in Yugoslavia, and retribution-related killings were committed just after the war ended.

In Asia and the Pacific, between 3 million and more than 10 million civilians, mostly Chinese (estimated at 7.5 million), were killed by the Japanese occupation forces. The best-known Japanese atrocity was the Nanking Massacre, in which 50 to 300 thousand Chinese civilians were raped and murdered. Mitsuyoshi Himeta reported that 2.7 million casualties occurred during the Sankō Sakusen. General Yasuji Okamura implemented the policy in Heipei and Shantung. Axis forces employed biological and chemical weapons. The Imperial Japanese Army used a variety of such weapons during its invasion and occupation of China and in early conflicts against the Soviets. Both the Germans and Japanese tested such weapons against civilians and sometimes on prisoners of war. The Soviet Union was responsible for the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers and the imprisonment or execution of thousands of political prisoners by the NKVD in the Baltic states and eastern Poland annexed by the Red Army.

The mass-bombing of civilian areas, notably the cities of Warsaw, Rotterdam and London, included the aerial targeting of hospitals and fleeing refugees by the German Luftwaffe, along with the bombings of Tokyo and the German cities of Dresden, Hamburg, and Cologne by the Western Allies. These bombings may be considered war crimes. The latter resulted in the destruction of more than 160 cities and the death of more than 600,000 German civilians. However, no positive or specific customary international humanitarian law with respect to aerial warfare existed before or during World War II.

This graph shows the casualties of World War II (Source: Wikimedia)

Concentration Camps, Slave Labor, and Genocide

The German government led by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party was responsible for the Holocaust, the killing of approximately 6 million Jews, 2.7 million ethnic Poles, and 4 million others who were deemed “unworthy of life” (including the disabled and mentally ill, Soviet prisoners of war, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Romani) as part of a program of deliberate extermination. About 12 million, mostly Eastern Europeans, were employed in the German war economy as forced laborers.

In addition to Nazi concentration camps, the Soviet gulags (labor camps) led to the death of citizens of occupied countries such as Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, as well as German prisoners of war (POWs) and Soviet citizens who were thought to be Nazi supporters. Of the 5.7 million Soviet POWs of the Germans, 57 percent died or were killed during the war, a total of 3.6 million.

Japanese POW camps, many of which were used as labor camps, also had high death rates. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East found the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1 percent (for American POWs, 37 percent), seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians. While 37,583 prisoners from Great Britain, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and 14,473 from the United States were released after the surrender of Japan, the number of Chinese released was only 56. At least five million Chinese civilians from northern China and Manchukuo were enslaved by the Japanese between 1935 and 1941 for work in mines and war industries. After 1942, the number reached 10 million.

The Effects of the Second World War

By the end of the Second World War, it was evident that something had gone horribly wrong with Western civilization. For the second time in just over three decades, Europe had plunged into a terribly destructive war in which tens of millions of soldiers and civilians had died. The people of Europe learned more about the terrible atrocities committed by the Nazis in eastern Europe, especially the murder of six million Jews. These catastrophes, moreover, had followed the Great Depression of the 1930s and the failure of the League of Nations.

The Creation of the United Nations and New Economic Organizations

Despite the failure of the League of Nations to stop the outbreak of a second world war, many leaders still believed in the possibilities of international cooperation. It was generally believed that the League had been too weak to stop the aggressive maneuvering of Germany, Japan, and Italy; a stronger organization was therefore needed. Moreover, leaders hoped to avoid a recurrence of the Great Depression; one of the lessons, they believed, was that the Depression could have been avoided had countries not raised tariff barriers and shut off international trade. This led to a series of economic agreements and organizations to structure the postwar international economy.

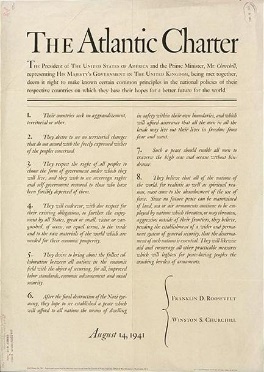

The first attempt at defining what the postwar world would look like was the Atlantic Charter. In the Charter, which was signed by 26 countries, including the United States and Great Britain, the signatories pledged to fight for better economic and social conditions for the people of the world and the end of subjugation and aggression. The Atlantic Charter called for freer trade and freedom of the seas. Its precepts were not binding, though they were forerunners of later wartime agreements. More importantly, the Atlantic Charter was an agreement between a group of countries with diverse interests; it was proof that countries could work together.

A printing of the Atlantic Charter (Source: Wikimedia)

Further attempts to define world organizations attracted more countries. Most importantly, the Soviet Union joined discussions about postwar organizations. At a crucial set of discussions at the Dumbarton Oaks mansion in Washington, DC, from August 21 to October 7, 1944, many countries, including the Soviet Union, China, the United States, and Great Britain, agreed on the guidelines for a postwar United Nations. This included the formation of the United Nations Security Council, on which those four countries would be permanent members. They would also have a veto over any Security Council resolutions. France would later win a permanent Security Council seat and a veto.

Just prior to the Dumbarton Oaks conference, from July 1 to 22 the Allied countries met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to discuss the makeup of the postwar economy. The conference eventually agreed to create the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which is now known as the World Bank. The main idea behind the conference was to ensure continued prosperity through collaboration, American-led relief (in the case of the IBRD), and free trade.

When the Allies finally defeated the Axis powers, the United Nations became a reality. On June 25, 1945, fifty countries adopted the draft charter of the United Nations unanimously. They signed it the next day. The UN held its first General Assembly and its first Security Council meeting in January 1946 in London; on February 1, 1946, Trygve Lie, a Norwegian, was named the first UN Secretary-General.

|

|

IN THEIR OWN WORDS |

|

The Preamble to the Charter of the United Nations explained its purpose in these words: WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS DETERMINED to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, AND FOR THESE ENDS to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours, and to unite our strength to maintain international peace and security, and to ensure, by the acceptance of principles and the institution of methods, that armed force shall not be used, save in the common interest, and to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples, HAVE RESOLVED TO COMBINE OUR EFFORTS TO ACCOMPLISH THESE AIMS. Accordingly, our respective Governments, through representatives assembled in the city of San Francisco, who have exhibited their full powers found to be in good and due form, have agreed to the present Charter of the United Nations and do hereby establish an international organization to be known as the United Nations. You can read the complete Charter here. |

|

|

Click and Explore |

|

Explore the United Nations and learn more about its role in the world today by visiting the UN website.

|

The Nuremberg Trials

Following the war, the victors sought to assign individual responsibility for the crimes of the Nazis; they did this through military tribunals. The most notable of these tribunals were the Nuremberg trials, held at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg from October 20, 1945 to October 1, 1945.

During World War II, the Allies’ desire to punish the Germans solidified. In 1942, the Soviet Union, China, the United States, and Great Britain issued the Declaration of the Four Nations on General Security, which stated the Allies’ intention to prosecute the major war criminals responsible. This intention was reiterated at the Yalta Conference in Berlin in 1945. The Allied powers agreed on the legal basis and format of the trial on August 8, 1945, in the London Charter, and allowed France a place on the tribunal. Nuremberg, inside the U.S.-controlled zone of West Germany, was chosen as the location for the trials despite the protest of the Soviets, who wanted Berlin to host the trials. Nuremberg, however, was largely intact following the destruction of the war and the Palace of Justice was mostly undamaged, large enough to hold the trials, and was adjacent to a large prison complex. The city had also been the site of the Nuremberg Rallies (Nazi propaganda rallies held in the 1920s and 1930s) where the Nuremberg Laws, which codified Nazi ideology and anti-Semitism, were introduced. As such, the city was seen as a fitting place to try the leaders of the war. The trials were restricted to the “punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis countries.” Two hundred German war criminals were tried at Nuremberg, while 1,600 others were prosecuted under the same principles through subsidiary tribunals.

A photograph of Defendants on trial at the Nuremberg trials. The main target of the prosecution was Hermann Göring at the left edge on the first row of benches. (Source: Wikimedia)

The International Military Tribunal prosecuted three categories of crimes: crimes against peace (such as planning, preparing, initiating, waging a war of aggression), war crimes (violations of the laws or customs of war, such as the murder or ill treatment of prisoners of war or civilians), and crimes against humanity (murder, extermination, deportation, enslavement against any peoples during or before the war, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country in question). The third category of crimes was, of course, closely connected to the discovery of the German death camps; nearly three million Jews and one million other Europeans (including Roma, Soviets, Poles, communists, and homosexuals, among others) were murdered in the camps.

The first session of the International Military Tribunal opened in November 1945 and indicted 24 individuals and seven organizations, including the leadership of the Nazi Party, the Gestapo (secret police), and the Sturmabteilung (or SS, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party). Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels were not tried, as all three had committed suicide in the months before the indictments. The majority of those convicted were sentenced to death by hanging. This trial also helped to set a precedent for future convictions.

More trials followed at Nuremberg that dealt with other segments of society most to blame for making the war and its atrocities possible. These trials focused on people in the medical, legal, and industrial sectors of German society. The medical trial was held from December 1946 to April 1947. Twenty-three of the leading doctors in the Nazi program were tried for their experimentation in the concentration camps and in hospitals. Sixteen were found guilty and seven were executed. This trial led to the creation of the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for medical experimentation on human beings.

|

Click and Explore |

|

Visit the PBS website, Holocaust on Trial, to learn more about the experiment conducted by Nazi doctors. |

The German legal system was another focus of the Nuremberg trials. Sixteen defendants from the Ministry of Justice, the Special Courts and the People’s Courts were tried to determine if they were responsible for enforcing and furthering the Nazi program of racial purity through racial laws. Ten of the defendants were found guilty. Other trials dealt with business leaders who were charged with enabling the Nazis to prepare for war and engage in war crimes. IG Farben, for instance, was a conglomerate of German chemical firms that supplied the death camps with Zyklon B, the poison gas used in the gas chambers. They also helped the war effort in Germany by developing a process to synthesize gasoline and rubber from coal. Of all the Nuremberg trials, these were the least successful. The nature of the crimes was ambiguous and contested. In the IG Farben trial, for instance, of the 24 defendants, 10 were acquitted and 13 were sentenced to prison sentences of 1½ to 8 years (one of the defendants, Max Brüggemann, was removed from the trial because of illness).

|

Watch and Learn |

|

Watch the following two short videos linked to the Nuremberg Trials. The first, Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps, was produced by the US armed forces and used as evidence in the trials. The second is a 1946 newsreel summarizing the sentencing at the Nuremberg trials. |

In general, however, the process of adjudicating war crimes was quite successful. The public nature of the trials brought attention to the atrocities of World War II and led to a sense of German responsibility and shame. The trials also instilled universal notions of justice that are binding, even if not written in international law. The main principle – that the world community was willing to prosecute indisputably criminal acts, even acts taken by the people in power in a major country – has guided subsequent legal campaigns against disreputable regimes ever since.

The Reconstruction of Europe after the Second World War

Europe was a continent in tatters after the Second World War. Tens of millions were dead, so the labor force had been depleted. Many cities were utterly destroyed, and much of the continent’s infrastructure lay in ruins. The destruction extended to the land; Europeans had little to eat in the first years after the war. State treasuries were bare from wartime borrowing. Millions of refugees crisscrossed the continent, as millions of expatriate Germans were expelled back to Germany and millions of prisoners of war who had been held by the Germans tried to return home. Many Jews who had survived the Holocaust looked to leave Europe entirely and start a new life in Israel. This reading outlines the fundamental problems that faced Europe after the Second World War.

|

Before Reading the Next Section — Watch and Learn |

|

Watch both of the following videos to learn more about the Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust: World War II and the Holocaust, 1939-1945

|

Economy

The end of the Second World War may have brought prosperity in the United States, but in Europe it heralded the return of economic depression. Industrial production had slumped badly to one-third of production levels in 1938, which were already low because of depression. Agricultural production was badly damaged from over-cropping and a lack of fertilizers, so fields were depleted of nutrients. The harvest was half of 1938 levels, so food rationing persisted after the war and some countries had to reduce rations even further.

Infrastructure had been badly damaged throughout the war, and many cities had been completely destroyed; examples include Coventry, Berlin, Rotterdam, and Warsaw. There were major transportation problems; the Germans’ scorched-earth policy had led to, for instance, a 300-mile stretch of the Rhine River having only one bridge. Above all, Europe had to cope with the massive loss of life from the war. An estimated 40 million Europeans had died in the war; many more had been crippled psychologically or physically from the fighting. This added up to the complete disruption of international trade patterns and payments.

In 1945, state borders had not all been determined, and new state governments were not yet in place. Investors nonetheless wanted stability, or at least a predictable level of risk. The huge reparations payments imposed on Germany after the First World War had had a major impact on German economy, and there was a spirited debate after the Second World War about how much the reparations should be. The Soviets wanted Germany to pay substantial reparations, having endured the greatest destruction of the war. Britain and the United States wanted fewer substantial reparations, however, because they did not want to weaken the position of western Europe as a whole.

Beginning in July 1945, the United States poured money into Europe through the United Nations Relief & Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). By 1948, aid levels had reached $25 billion, but they had given money to Europeans indiscriminately and could not account for some of it. Much of the relief money had gone to providing food, shelter, and medical care; while crucial, these were short-term solutions to keep the population alive and would not assure long-term stability. Much of the money, moreover, was given in the form of loans, not as gifts or grants. This just increased Europe’s financial problems.

In Europe, 1947 became a year of crisis. A wave of strikes and unrest swept over the continent in response to the economic instability. Communists had much success in western European elections, exploiting a backlash against right-wing politicians. The Communists had led resistance movements during the war, so these victories were partly in recognition of their work. Nonetheless, their victories frightened conservatives, in Britain and the United States especially, as they feared the spread of Communist control over the entire European continent. At the same time as these electoral victories, the Soviets were consolidating control over Eastern Europe in accordance with the wartime agreements.

There had been a harsh winter in 1946–47, and Europeans still coped with food and fuel shortages. However, 1947 witnessed a crisis of confidence in the future of Europe among the general population. They had expected victory against the Nazis would create a better Europe, but they began to believe it would never happen. No one wanted to accept recovery to 1938 economic levels, but it appeared that this was the best they could do.

At this time, there was also an international debt crisis. Investors expected European countries to pay back loans, but Europeans were still exporting very little and needed to import more. After the experience of the 1920s, when countries defaulted on their payments, investors wanted repayment in gold, U.S. dollars, or pounds; this further undermined the value of European currencies and continued the economy’s downward spiral.

The economic downturn coincided with a crisis over Greece in August 1946. The Soviets demanded certain areas in the Bosporus; the Bosporus is the only exit out of the Black Sea that leads to the Mediterranean, and the Soviets wanted a base there. The British feared that the Soviet base would threaten British control of the Suez Canal in Egypt. The Russian move also threatened Greece, which was considered under the British sphere of influence. Greece was embroiled in a civil war between communists and the British-supported royalist forces. By February 1947, Britain no longer had the resources to support the royalists in Greece and anti-communists in Turkey.

With the European world seemingly crumbling, the United States moved to take a more commanding role in the world. First, President Truman established the Truman Doctrine. The United States would act anywhere in the world where communism threatened the growth of democracy. The Truman Doctrine guided American foreign policy – and how the United States treated the Cold War – for the next four decades. The United States government also began a much larger relief plan for Europe – the Marshall Plan. Announced in 1948 by Secretary of State George Marshall, the plan provided for an enduring American relief presence in Europe and underwrote the European economic miracle of the 1950s.

An official photograph of President Harry Truman (Source: Wikimedia)

Beginning of European Integration

As the United States began to involve itself more fully in European affairs, western European countries began to band together for mutual assistance. The first instance of this was the Treaty of Dunkerque, which Britain and France signed in March 1947. The treaty stipulated that in the event of an attack on either country by Germany, the other would come to its aid. This expressed the continuing French concern about a strong Germany.

Shortly thereafter, Franco-British military cooperation expanded to include the Benelux countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg). The Treaty of Brussels, which the five countries signed in March 1948, was another mutual defense treaty. If anyone attacked one of the five countries, the other four would be bound to come to their aid. This time, however, it was written to defend against more general threats, not just those from one country (i.e., Germany). This reflected the growing belief that the greatest threat to Europe came from the Soviet Union. It also, however, reflected that these countries recognized their own military weakness. Since they were unable to stand on their own, they sought each other’s assistance.

Nonetheless, the five countries of the Treaty of Brussels were hardly a defensive juggernaut; they had all experienced the destruction of the war and were mired in an economic depression. European countries knew that they needed to build up their military forces again, but they could not do so given the state of their own finances. The only western European country with the potential to contribute a large army to Europe was Germany; no one wanted to rearm Germany, however, fearing that it could turn against the rest of Europe once again.

Thus, European policymakers welcomed American suggestions for a defensive alliance, which was suggested in 1948. This, European leaders presumed, was better than a simple guarantee from the Americans to defend Europe. On April 4, 1949, the five countries of the Treaty of Brussels joined the United States, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Italy, Norway, and Portugal in the North Atlantic Alliance (known as NATO). This integrated European militaries into the American Cold War fight, but, crucially for Europeans, it secured the United States’ cooperation in the event of a Soviet attack.

The Minorities Problem

When the victors of the First World War sat down at the postwar peace conference in Paris to draw the map of Europe in a way that would ensure lasting peace, they proved unable to sort out the minorities scattered across the countries of eastern and central Europe.

The reasons for such large minority populations were largely historical; for centuries, eastern Europe had been the preserve of large empires; to the south, the Ottomans, in central Europe, the Habsburgs, and in the north, the Russians. Citizens were permitted to move anywhere inside these empires, and they often did, for various reasons. Germans often lived within the territories of the Habsburg Empire, for instance, because they became government administrators in occupied territories. Other groups often moved within the empire for work. Jews were restricted to the cities, and often stayed in areas where they were welcomed – in eastern Poland, for instance, or the Greek city of Salonica. In the Balkans, the large Muslim minority was a reminder of the Ottoman presence there.

When these empires disintegrated at the end of the First World War, the victorious Allies did not know how to deal with the minorities. In most cases, they accepted the principle of majority rule; if there was a majority of Czechs in the Sudetenland, for instance, then the Germans there were given legal protections but had to live under Czech rule. The minorities treaties, which the countries of the Balkans and Eastern Europe signed, were supposed to ensure that minority populations were not a problem.

However, few countries followed the precepts of the minorities treaties. The problem was compounded when the countries of Eastern Europe took territories from their neighbors. Hungary, for instance, lost much of its territory throughout the war; its people dreamed of the day when it would recover those territories. The Poles, meanwhile, conquered parts of Ukraine and Lithuania that contained only a Polish minority. Jews, who lived throughout Eastern Europe, were persecuted in most countries. The greatest problem was the Germans; the Nazis had made a big issue of the rights of Germans living outside Germany, and this was their pretext for taking over the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, and for invading Poland. This proved the failure of the Paris Peace Conference’s attempts to deal with minorities.

One interwar solution eventually became the template for the treatment of minorities in the late 1940s: population transfer. During the conflict between the Greeks and the Turks from 1920 to 1923, the two countries agreed to exchange minority populations. Greeks living in Turkey were forced to move to Greece, and likewise. In many situations, the “home country” had not actually been home for these people for hundreds of years. Population transfers became the norm in post–Second World War Europe. This created a displaced-persons crisis in much of the continent. First, millions of refugees from the war were trying to get home. Citizens of every European nationality, including two million French and 1.6 million Poles, had been brought to Germany for forced labor during the war; these people had to return home. Many, however, no longer had homes to return to. This raised fears of pandemics in the temporary settlements where people were forced to live.

More than ten million Germans lived outside Germany at the end of the Second World War; some had settled after the German army had conquered territories, while most others had been living outside Germany for a long time. They faced terrible retribution for the Nazis actions. Most were unceremoniously expelled from their homes and forced to move back to Germany in likely the largest population transfer in world history. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, died in the expulsions; few Europeans had sympathy for them. Those who made it back to Germany encountered a country of rubble; more than three million homes had been destroyed in the war.

A photograph of German families being forced to leave their homes in Sudetenland after World War II (Source: Wikimedia)

Other population transfers took place in Europe as well. Many occurred because the Soviet Union essentially moved Poland about 50 miles westward. Poland took much eastern German territory, therefore, regardless of whether the Poles had any ethnic or historical claim to it. This was intended to compensate the country for the wide swath of eastern Poland that the Soviets repatriated to Russia (today this area is part of Ukraine). For instance, Poles from the city of Lwów (today L’viv, Ukraine), which in 1945 was on the Russian side of the border, were moved to cities like Wrocław (formerly called Breslau, when it was within the borders of Germany). Seventy percent of the buildings in Wrocław had been destroyed during the war and its German population had been expelled, so it needed new inhabitants. The city took decades to rebuild, and through most of that period the Poles tried to rebrand the city as Polish.

Similar experiments took place throughout the rest of Europe as minorities were displaced. Europe’s minorities problem disappeared for forty years until the disintegration of Yugoslavia, another multiethnic entity. Population transfer was a deadly solution, but its adherents thought it was effective; Germans now only lived in Germany, and countries like Poland no longer had minorities to speak of.

The Creation of Israel

Population transfer from one European state to another was not an option for the remaining Jews of Europe. Six million had died in the Holocaust, and those who remained no longer believed in the strength of European state protection. Tens of thousands of Jews had immigrated to British-controlled Palestine during the interwar period, and this option became much more inviting after the Holocaust. Europe was no longer a home for Jews; even those areas where Jews had been historically welcome, like the shtetl in eastern Poland or the city of Salonika, were tainted by the memories of the Holocaust. Moreover, some Jews who survived the war returned to their homes only to face pogroms. Others were turned away; their houses had been occupied during the war and the new owners refused to leave.

Jewish resistance groups in Palestine had begun to fight British rule as the Second World War drew to a close. The British, who were impoverished and tired of fighting, decided to pull out of Palestine in 1947. The newly formed United Nations considered the question for several months, and on November 29, 1947, released a plan to partition Palestine between Jews and Palestinian Arabs. The Jews accepted the plan, but some key Arab organizations rejected it. The British mandate was set to expire on May 15, 1948. The day before, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared the formation of the State of Israel. On May 15, the armies of Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, and Iraq invaded. The war lasted about a year; the agreed ceasefire terms gave the Gaza Strip to Egypt and part of the West Bank to Jordan. The Israelis had barely prevailed, and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled.

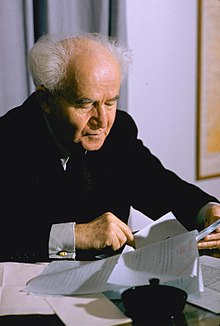

A photograph of David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel (Source: Wikimedia)

Over the next decade, more than a million Jews immigrated to Palestine. Most came from Europe (many were Holocaust survivors) and the Arab lands, some of which had expelled all Jews. The massive influx of citizens created a housing shortage in the small country. Many immigrants – perhaps 200,000 – lived in tent cities until a reparations agreement with West Germany in 1952 brought the funds needed to build more houses.