1.3 From Data to Information to Knowledge

We have been talking about data, information and knowledge in all previous sections of this chapter. Nonetheless, we have not defined any of these concepts. In this section of the chapter, we briefly define each of these concepts and include two different ways of thinking about the relationships among them. These three concepts are usually discussed in the context of organizational innovation and adaptation to a changing environment. Government faces complex social problems that require collaboration from different levels of government, private organizations, and nonprofits . These new collaboration patterns challenge the traditional hierarchical government organization, deriving on the need to innovate in the structure of institutions and the creation of networks of public and/or private organizations needing to share what they know about a specific problem domain or policy area. Innovation is also needed to respond to citizens demanding from government levels of service similar to the ones they are used to getting from private companies.

Data, information and knowledge are frequently represented as a hierarchy, where data is at the bottom and knowledge is at the top (see Figure 1.4). The pyramidal shape of the figure suggests that data is much more abundant than information and both of them are more abundant than knowledge. There is no full agreement on the definitions of these terms, but data usually refers to the basic representations of concepts or other entities, like the temperature outdoors. Information usually refers to data that is processed in a way that is meaningful to an individual. For a given individual, for example, 25 F mean that “it’s cold outside”. Finally, knowledge is usually defined as “actionable” information. In other words, knowledge is information that has been appropriated by an individual and changes their actions or behavior; when it is cold outside, I need to wear a coat. From some perspectives, data-driven approaches are understood as protocols and systems to get data and transform it into information and knowledge that allows for better public policy.

Figure 1.4 A Hierarchical view of data information and knolwdge.

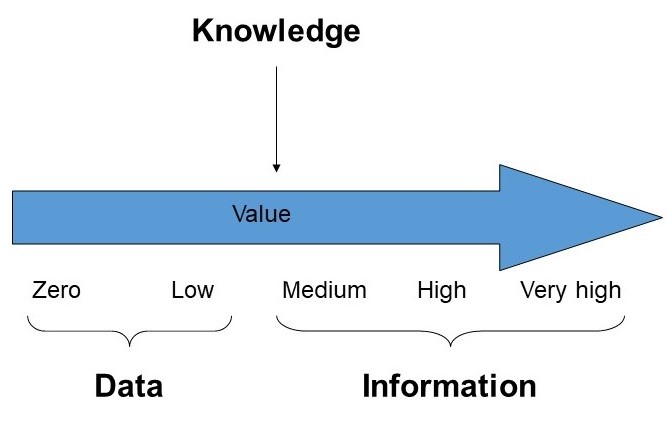

A potential weakness of this hierarchical view of data, information and knowledge is the assumption that data naturally occurs in nature, and some experts would argue that data are human constructs that we decide to collect based on our knowledge of a policy domain or a problem. In this way, an alternative view of the relationship among data, information and knowledge, knowledge is at the center (se Figure 1.5). We use knowledge to specify what is important data to be collected and also how to transform these data to add value to it.

Figure 1.5 Knowledge as a necessary factor to increase the value of data and transform it into information

Knowledge in this way is at the center for innovation and data-driven approaches, and and managing knowledge may be understood as a key organizational activity. Some experts consider knowledge as an accumulation of actionable information or intellectual capital. Some others consider knowledge as a dimension of practice. In this way, projects to manage knowledge take two different forms, commonly characterized as person to person and person to document, responding to each of these views. Although both perspectives recognize that knowledge resides in people, person-to-document projects consider knowledge as a codifiable asset to manage. Examples of person-to-document projects include knowledge repositories, decision support systems, expert systems, data warehouses, data lakes or executive information systems. A common example of these systems are libraries and databases that collecct and organiza articles, books, maps and other digital materials on many different domains of knowledge. This repositories can also be organized around a single domain. The federal Mexican government, for instance, maintains a public repository of government procedures known as Tramitanet (https://www.gob.mx/tramites). Person-to-person projects assume that knowledge is embedded in practice, and they look to promote innovation and knowledge sharing by establishing means to connect people. Knowledge directories, groupware, customer relationship management (CRM), workflow management tools, and communities of practice are examples of this kind of projects. The University at Albany Experts is an example of these repositories.

Further Readings

- Zins, C. (2007). “Conceptual Approaches for Defining Data, Information and Knowledge” Journal of the American Society for Informtion Science and Technology. 58(4):479-493

Attribution

By Luis F. Luna-Reyes, and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.