8.1 Models and Decision Making

Decisions, decisions, decisions

Before trying to understand the use of models and data to support decision making, we want to make a quick reflection on the decision process itself. Decisions are a daily problem for any public manager and policy maker, but they are also important for most human activity. That is, we make decisions frequently during the day and in many different domains: when to wake up? what to wear?, or what to eat for breakfast?

There are several ways in which we can think about clasifying decisions. Figure 8.1 in this chapter suggests at least two different ways. The first approach involves the level of complexity of the decision expressed as how much structure there is in the problem itself. Think for example on the accounting and finance system of any organization. Many decisions have to be made about how to record transactions in the accounting system, and these decisions belong to the more structured ones, given that accountants have a well-defined set of rules on how to register them, a defined set of accounts where those transactions can be recorded, and they even have ways of checking if the records are balanced by calculating the total of credits and debits. If they are equal, the records are balanced correctly. On the other hand accountants and financial managers have also problems related to, for example, managing portfolios of investments or policies. In other words, how much to spend in educations or health? These decisions are less structured in the sense that it is harder to define what is the necessary data to make the assessment, what methods to use to use that data to make the decision, or even what is the right goal.

Another way of classifying types of decisions is by thinking on the uncertainty involved with data and other inputs, as well as with the potential effectiveness of the final choice compared to other alternatives at hand. As suggested in Figure 8.1, different types of decision models are potentially more helpful for some types of decisions. Another way of thinking about types of decisions could be the frequency of those decisions. There are decisions that are made recurrently, and there are some other decisions that are not made that frequently. For example, decisions about eligibility for public programs are in the category of recurrent decisions. Public managers assessing eligibility for a variety of public programs such as medicaid or tax credits make these decisions on a regular basis, maybe many of them every day. On the other hand, there are decisions that are not made that frequently such as large investments.

How Do we Make Decisions?

Although through this chapter and the next ones we will discuss assumptions and methods of several decision models, an important starting point is to acknowledge that models and data do not make decisions, but people makes decisions.

An interesting anecdote attributed to John Little (see sidebar), illustrates that fact with the following statement of a business analyst during an interview where a researcher (presumably John Little) was asking about how models were used in this organization.

I come to work every morning and input into the computer the necessary parameters to get the production program for the day. I take the results from the computer and take them to the operations manager… They take a look at the results, and ask me to make some parameter adjustments… so I go back to the computer, make the adjustments and prepare additional reports… I print them out and bring them back to the manager… They take one more look at the reports and ask me to again make additional adjustments and prepare more reports… This process repeats several times until they get the guts to make a decision and define the production program for the day…

In this way, it is always a good starting point to reflect on what type of decision maker you are. Take out a piece of paper and think of a recent decision that you have made and try to describe it with as much detail as possible. What was the decision? what information you use? How did you use the information? How did you reach a conclusion?

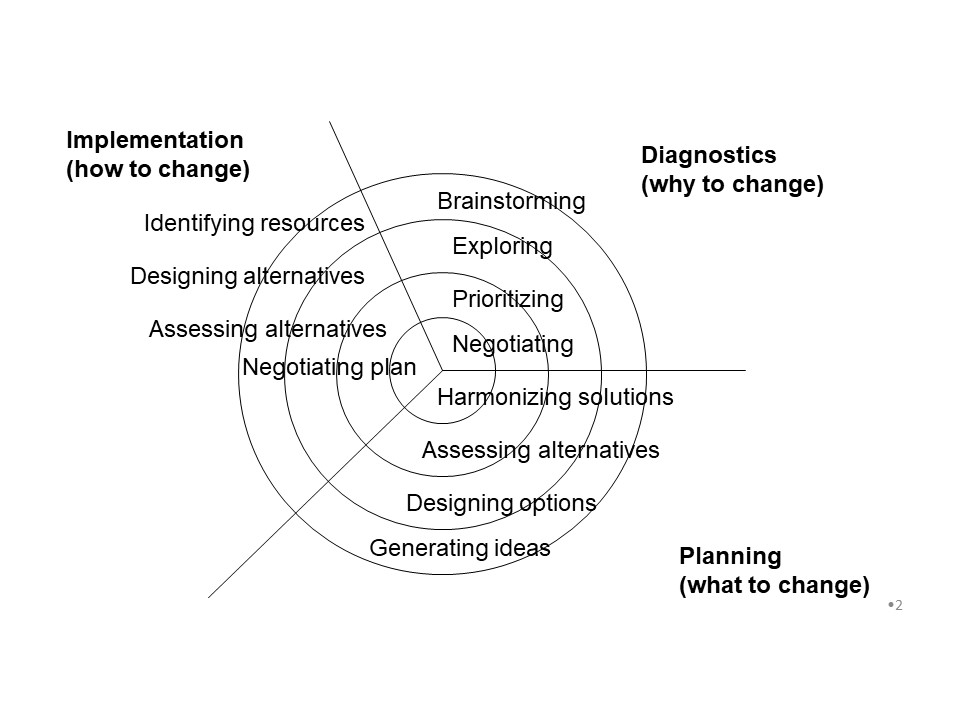

We make decisions in many different ways, and when making decisions we use a combination of intuition and analysis. In other words, just like the manager in the anecdote, we use a combination of data and guts in each decision we make. We tend to trust more intuition or analysis depending on our own strengths. In general, there are three main components for any decision we make: (1) Alternatives, (2) Goals and (3) Decision rule. Alternatives are all potential paths that we can follow to solve the decision process. Goals involve our objectives, and also a way of measuring how well we are accomplishing them, and a decision rule involves how do I use data, analysis and intuition to reach a conclusion. Making decisions is then regularly a process of thinking about goals, generating alternatives and figuring out how to make a choice. Figure 8.2 includes a general model for decision making. The model reflects the kinds of decisions that a manager makes, grouping them as diagnostic (why to change), planning (what to change) and implementation (how to change) decisions. As the pictude suggest, in each category is possible to think about that process of generating ideas, figuring out alternatives and goals and deciding on a solution.

Figure 8.2 A General Model for Decision Making Approaches

Models play an important role in helping us how to think about alternatives, goals and all of them provide a procedure or rule to make a choice. So get ready to learn more about this in the following chapters.

Assessing Decisions

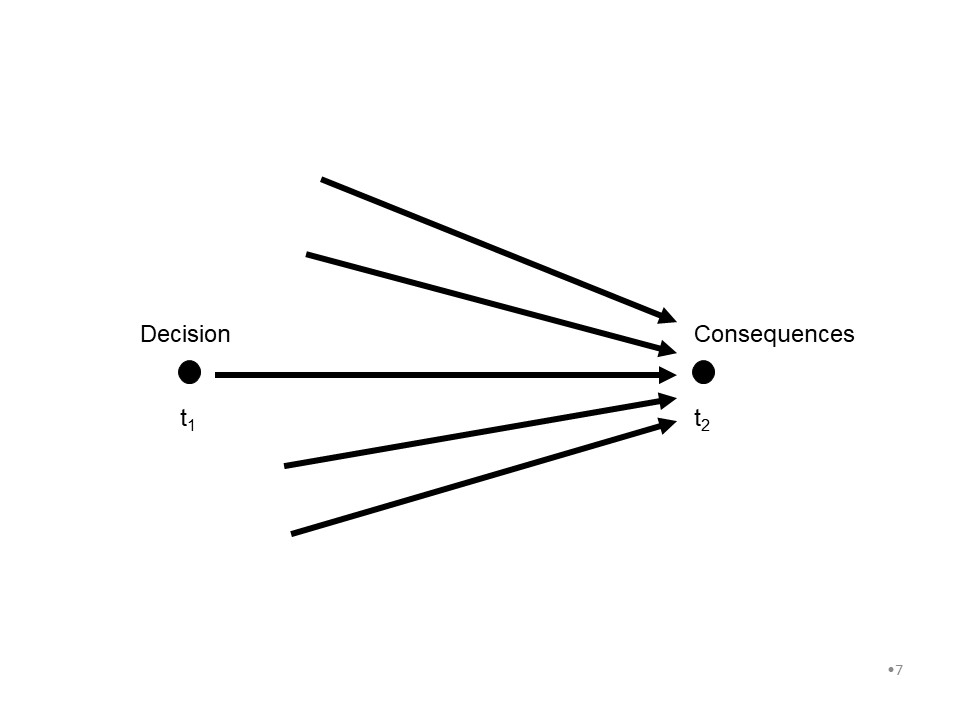

I would like to finish this section of the chapter with a brief reflection on how to assess our decisions. It is common to think that good decisions will lead to good consequences, and thus looking at the consequences appears to be a good way of assessing the value of our decisions. Unfortunately, it is most common that any decision we make would only play a limited role on the goals that we want to accomplish, particularly when we are considering important policy problems (see Figure 8.3). In this way, besides thinking on the effectiveness of each decision in accomplishig goals, we may also consider to include some parameters about the process of making the decision. Did we made a good job identifying important goals and measures? Did we spend enough effort generating alternative solutions? Did we use the best possible data? Thinking about the process and making sure that we are using sound methods and data (and the necessary amount of intuition too) may help us not just to better understand how do we make decisions, but also contribute in developing our skills as decision makers.

Figure 8.3 The impact of decisions on results

Attribution

By Luis F. Luna-Reyes and Erika Martin, and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.