1.33 Quadratic Solution to IRR

As just observed, when a project reflects (multiple) negative interim future cash flows, we get a “quadratic solution,” yielding multiple IRRs. Suppose a firm, for example, has a cost of capital, or “hurdle rate,” of 15%, but the dual quadratic solutions reflect both a 10% and a 20% IRR. Do you accept or reject the project? Most probably, you should utilize an alternative decision rule. The following example illustrates this troubling outcome.

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| FCF | ($1,000) | $3,200 | ($2,400) |

This is equivalent to:

[$3,200 / (1 + IRR)1] – [$2,400 / (1 + IRR)2] – $1,000 = 0

A quadratic formula will have three constants and two variables. We will convert the formula created above to its quadratic form as in:

ax2 + bx1 + c = 0

First, to simplify, let’s decimalize (just for this moment) the numerator.

[$3.2 / (1 + IRR)1] – [$2.4 / (1 + IRR)2] – $1 = 0

Next, we will first substitute “x” for “1 + IRR.”

[$3.2 / (x)1] – [$2.4 / (x)2] – $1 = 0

In multiplying the expressions by x 2, we rid ourselves of the divisor:

3.2 (x)1 – 2.4 – 1 (x)2 = 0

3.2x – 2.4 – x2 = 0 =

Last, we reorder and change ALL the signs (this is equivalent to moving the expression to the other side of the equal sign) so that our formula now looks like a quadratic:

x 2 – 3.2x + 2.4 = 0

Now, we can solve for x.

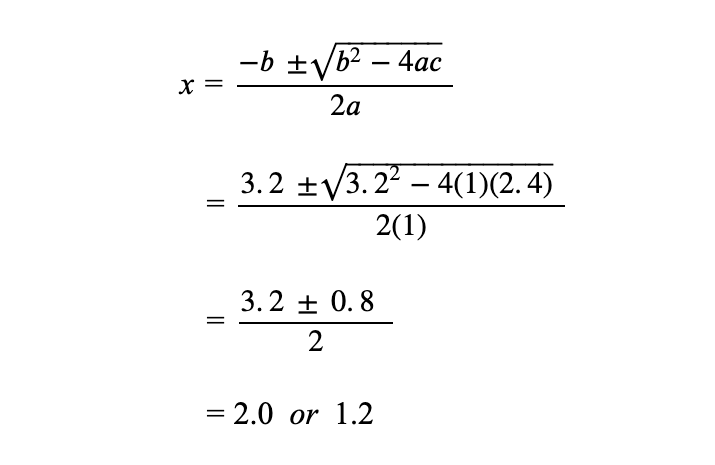

This is your standard quadratic equation the solution for which (i.e., solving for “x”):

This “famous” general quadratic solution is simply the formula, which solves for “x.”

Finally, since we substituted “x” for “1 + IRR,” the IRR = x – 1. Thus, we get two possible IRRs: 100% AND 20%! Which is “correct”? Both? Mathematically, yes! For us in this context? It i snot helpful! We must therefore reject the method.

It should be noted that the quadratic solution works only if there are just two future cash flows of which one is negative; if, as is likely, there are more than two, the solution cannot conform to the quadratic formula (i.e., x2 + x1 + 1 = 0) and its famous solution.

As it works out in Mathematics, every time we get a negative interim cash flow, we get an additional IRR. In this example, we had two negative numbers – ($1,000) and ($2,400), hence we observed two IRRs. Had there been only one negative cash flow, say the initial outlay, we would have had only one IRR! It is not terribly unusual for a project to have a negative future cash flow. Often, as an example, the equipment in which the company has invested will require a major overhaul at some point, causing that year’s FCF to come in negative.

As an exercise, calculate the project’s NPV using 15% and, alternatively, 25% as discount rates. Under this alternative rule of thumb, would you accept or reject the project?