Skeletal Muscle Tissue and the Neuromuscular Junction

In an earlier chapter, Introduction to Muscle Tissue, we explored and compared the three types of muscle tissue. This chapter will take a deeper look into skeletal muscle tissue, as it describes the microscopic anatomy of the muscular system. It is easy to confuse skeletal muscles, at the organ level, with skeletal muscle tissue. Skeletal muscles are organs that allow movement of our skeletal system, support our joints, allow us to communicate and interact with our environment. Skeletal muscles (organ level) are primarily made of skeletal muscle tissue. However, it is important to remember that organs are made of two or more tissue types. In addition to skeletal muscle cells, our skeletal muscles also contain the following structures:

- Blood vessels (contain endothelium, smooth muscle tissue, connective tissue) – blood flow to provide O2 and nutrients

- Motor nerves (contain neurons, connective tissue) – stimuli to contract

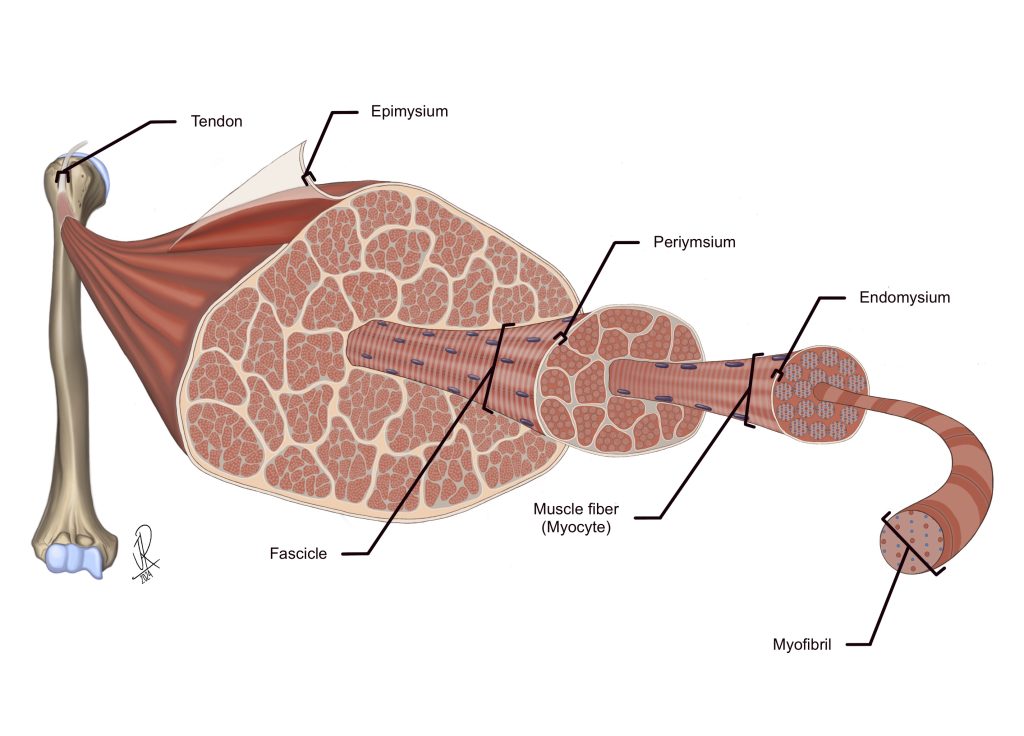

- Connective tissue sheaths (epimysium, perimysium, endomysium) – organize and provide organ-level structure

Skeletal muscle cell/fiber

As we discussed in a previous chapter, Skeletal muscle tissue is made of elongated (long) cylindrical-shaped cells. Skeletal muscle cells are so long that we refer to them as skeletal muscle fibers (don’t forget that they are actually cells!). Each cell contains many nuclei, so they are called multinucleated. The nuclei are peripherally-located, which means they are pushed against the inside of the plasma membrane. Skeletal muscle tissue is striated, a term that refers to its perpendicular “striped” appearance.

Figure 1: Skeletal muscle tissue in longitudinal section with and without illustration overlay

We use specialized names to describe the parts of a skeletal muscle cell. The cytoplasm is called the sarcoplasm, and the plasma membrane is the sarcolemma. Surrounding the sarcolemma of each skeletal muscle cell is a thin layer of connective tissue called the endomysium.

Skeletal Muscle Organization

Bundles of skeletal muscle cells, each surrounded by an endomysium, are called a fascicle. Each fascicle is surrounded by a layer of connective tissue called the perimysium.

The entire muscle, including the fascicles, blood vessels, and nerves, is surrounded by a thicker layer of connective tissue called the epimysium.

Figure 2: Organ-level depiction of a skeletal muscle, highlighting the connective tissue sheaths that coordinate organization of the muscle tissue. The epimysium surrounds the whole muscle, the perimysium surrounds muscle cell bundles called fascicles, and the endomysium surrounds the plasma membrane/sarcolemma of each muscle cell.

Figure 3: Skeletal muscle tissue in longitudinal and cross-section highlighting endomysium and perimysium, with and without illustration overlay

Skeletal Muscle in Longitudinal Section

When we view skeletal muscles in longitudinal section, they appear as long cylinders.

Skeletal Muscle in Cross Section

When we view skeletal muscles in cross section, they appear as collections of geometrically shaped cells. This is because we are viewing them from the end of the cell. The sarcolemma and endomysium will form a ring around the myofibrils (Figure 2 and 3). The nucleus will be visible pushed against the inner side of the sarcolemma.

The Neuromuscular Junction

The axon of a motor neuron can branch into many axon terminals. Many skeletal muscle fibers can be innervated by the axon of one motor neuron with branching axon terminals. We refer to the motor neuron plus all the muscle fibers it innervates as one motor unit. The junction of each axon terminal and the muscle fiber (muscle cell) is called the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). These two cells are not physically connected, but instead are separated by a very small space called the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) is released from the axon terminal and diffuses through the fluid in the synaptic cleft until it reaches and binds to specific ACh receptors on the muscle cell. These ACh receptors are only found in this specific area of the muscle cell membrane in close proximity to the axon terminal, called the motor end plate.

Figure 4: The neuromuscular junction (version A) with and without illustration overlay

Figure 5: The neuromuscular junction (version B) with and without illustration overlay

Chapter Illustrations by:

Jaylan Richardson

Georgios Kallifatidis, Ph.D.