72 George Herbert: The Temple

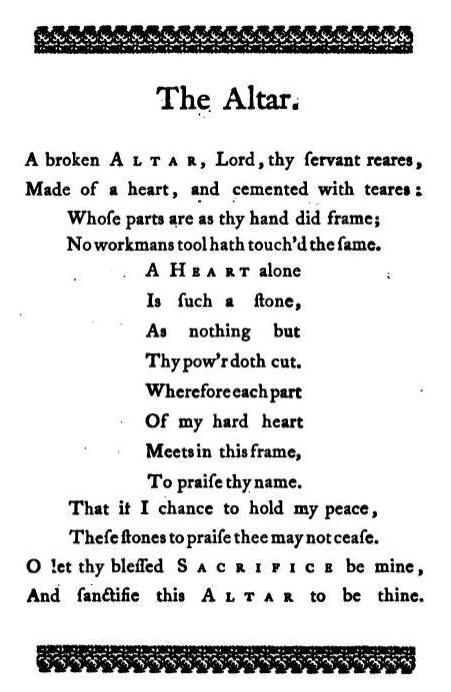

“The 17th-century text of George Herbert’s poem ‘The Altar'” by George Herbert. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Hani Kamee

Biography

George Herbert (1593-1633) was born in Wales and grew to be one of the most lauded orators and poets of his generation. Herbert’s father died when he was three, leaving his mother with ten children, all of whom she was determined to educate and raise as loyal Anglicans. Herbert left for Westminster School at age ten and went on to become one of three to win scholarships to Trinity College, Cambridge. He went on to receive two degrees (a BA in 1613 and an MA in 1616) and was elected a major fellow of Trinity. Two years after his college graduation, he was appointed Reader in Rhetoric at Cambridge, and in 1620 he was elected public oratora post wherein Herbert was called upon to represent Cambridge at public occasions and that he described as “the finest place in the university”(“George Herbert”). He would go on to serve in Parliament but ultimately gave up his secular life in favor of a quiet, parish post at St. Andrews’ church in Salisbury. Herbert was a conscientious and kind rector throughout his short life; he ultimately died of consumption at the age of 39 (“George Herbert”). His poems, often referred to as love poems to God, have caused him to be remembered as the greatest devotional poet in the English language.

Literary Context

The poems below, by the orator and Anglican cleric George Herbert (1593-1633), were first published in Herbert’s collection The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations which contains all of the poems he wrote in English (he also wrote in Greek and Latin) and was published posthumously.

He was part of the metaphysical tradition of English poetry, and all his poetry addressed religious themes (“The Altar (Herbert Poem)”). “The Altar,” the most famous of the collection, is regularly called a “pattern poem” or “shape poem” in which the form of the poem on the page is meant to mirror its visual image (in this case, an altar; “Easter Wings” is another example). Herbert had a playful style; in any case, the term is useful, since it suggests that for Herbert everything—including the shapes of the sonnets—can contain religious meaning. Herbert is ranked amongst the best of religious Christian writers or poets, and this sonnet conveys the experience of faith through verse.

Works Cited

“The Altar (Herbert Poem).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Altar_(Herbert_poem). Accessed 02 May 2020.

“George Herbert: 1593-1633” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, n.d., poets.org/poet/george-herbert. Accessed 02 May 2020.

Discussion Questions

- What is the significance of the “pattern poem”? Is it merely a “gimmick” or does it enhance meaning in this case?

- Is devotional poetry still relevant? Of what value is it to modern-day audiences?

- Do you think the rhyme scheme plays a major contribution to the poem? Why or why not?

- How does the poem help the reader understand the relationship between George Herbert and God?

- Can these be read as love poems? Might this explain their enduring appeal?

Further Resources

- A musical rendition of “The Altar” from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Albany NY

- A YouTube clip of Cambridge University’s Helen Wilcox discussing the importance of George Herbert

- A webpage with a complete version of Herbert’s The Temple

Reading: From The Temple

The Altar

Redemption

Easter

Rise heart; thy Lord is risen. Sing his praise

Without delays,

Who takes thee by the hand, that thou likewise

With him mayst rise:

That, as his death calcined thee to dust,

His life may make thee gold, and much more just.

Awake, my lute, and struggle for thy part

With all thy art.

The cross taught all wood to resound his name,

Who bore the same.

His stretched sinews taught all strings, what key

Is best to celebrate this most high day.

Consort both heart and lute, and twist a song

Pleasant and long:

Or since all music is but three parts vied

And multiplied;

O let thy blessed Spirit bear a part,

And make up our defects with his sweet art.

I got me flowers to straw thy way:

I got me boughs off many a tree:

But thou wast up by break of day,

And brought’st thy sweets along with thee.

The Sun arising in the East,

Though he give light, and th’East perfume;

If they should offer to contest

With thy arising, they presume.

Can there be any day but this,

Though many suns to shine endeavour?

We count three hundred, but we miss:

There is but one, and that one ever.

Easter Wings

The Affliction (I)

Prayer (I)

Jordan (I)

Church Monuments

The Windows

Denial

Virtue

Man

And both thy servants be.

Source Text:

Hebert, George. The temple Sacred poems and private ejaculations. University of Michigan, n.d, and is licensed under CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.