60 CONTEXTS: Faith in Conflict

“Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536” by Fred Kirk Shaw. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Allegra Villarreal

The English Reformation is usually attributed to the whims of a capricious king, Henry VIII, and his desire for a new wife. But this isn’t the whole story. At the tail end of the 14th century, John Wycliffe, a Roman Catholic theologian, called for a reform of Western Christianity and thus was founded the “Lollard Movement.” Lollards outlined “Twelve Conclusions,” which included a call for an end to clerical celibacy, pilgrimage, the belief in transubstantiation, religious war, and for a separation of church and state powers. They were a small group and their numbers reduced further when “Lollard” became a synonym for “heretic” but their ideas anticipated the larger Protestant Reformation by nearly 150 years.

Though the Protestant Reformation is often dated to the publication of Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses, it actually came four years later, in 1521, with the Edict of Worms which officially banned all citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or spreading Luther’s “heretical” ideas. Luther argued that the immense wealth of the Church and its hierarchical structure had created a system that rewarded corruption and encouraged vice. He was particularly critical of the practice of selling “Indulgences”— certificates that guaranteed absolution of sin in the afterlife—which connected to his belief that it was not through practice (giving charity, good deeds, ritual observance of holidays) but through faith alone that one could be saved (sola fide). This matter of salvation—and whether acts or faith guarantee it—was the heart of the Catholic/Protestant theological divide.

It is no coincidence that it happened when it did: the printing press made the dissemination of knowledge much easier throughout the Continent, specifically translations of the Bible from Latin into other languages, including English. Knowledge could now travel fast, especially among scholars and the upper classes; this is how, eventually, Henry VIII was exposed to Luther’s arguments. In 1521, he defended the Roman Catholic Church against Luther’s accusations, earning him the title “Defender of the Faith” from Pope Leo X. During this time, Protestants were brutally persecuted throughout England. But dynastic need and personal desire changed the course of English history.

Henry VIII, for his part, was never meant to be king. His other brother, Arthur, was crown prince and, at age 17, was married to Catherine of Aragon. Shortly after the wedding, Arthur took ill and died; Catherine asserted that they had never been able to consummate the marriage due to his illness and so she was betrothed to Arthur’s younger brother, Henry, in order to preserve the alliance with Spain. By all accounts, their marriage was a happy one but it did not produce a male heir. When Henry fell in love with one of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn, he attempted to annul his marriage on the basis of the previous marriage to his brother. This, he said, was a sin in the eyes of God and had cursed their union. His agenda, however, was clear: he wanted to marry Anne in the hopes of having a son to carry on the Tudor dynasty. But Catherine had her defenders, too, namely the Holy Roman Emperor (her nephew) who had more political influence than Henry in Rome. The Pope ultimately refused to grant the annulment. Anne Boleyn was recorded as a woman of “charm, style and wit” who likely played a key role in advancing Protestant ideas to the King. Breaking with Rome would serve two purposes: he could marry Anne and also have absolute control over both religious and secular affairs in his kingdom. After protracted battles in the early 1530s, England officially broke with Rome in 1536 establishing the Church of England with Henry as its head. Catherine was exiled from court and Anne eventually lost her life when she could not deliver on her promise to birth a future king (though, in the end, she did give birth to the woman who would become the most powerful Tudor monarch of all: Elizabeth I).

The aftermath was swift and brutal. Monasteries were sacked, monks and nuns encouraged to renounce their faiths and find spouses (as Luther and his wife, a former nun, had done), while any “graven images” (including crucifixions, venerated statues, relics, saints’ paintings, elaborate altarpieces) were defaced, stolen, or sold off to fill the king’s coffers. Services were now conducted in English, rather than Latin. Even with all these changes, the core rituals of Catholicism remained under Henry; when his son, Edward VI, succeeded him, he enforced a rigidly Protestant regime. He only ruled for six years before succumbing to illness at age 16. Mary, Catherine’s daughter, succeeded him and sought to establish the “old religion” in England through brutal persecution of Protestants (earning her the nickname she still carries: “Bloody Mary”). It was only with her successor, Elizabeth I (Anne’s daughter), that England achieved its “golden age” of relative peace and prosperity and where Protestantism gained its permanent foothold as the official religion of state.

Throughout the 16th century, both Catholics and Protestants were subject to brutal persecution under different regimes, and, as a result, each side had its venerated martyrs. Men and women who preferred to die than give up on their deeply held beliefs, trusting in the everlasting salvation guaranteed them by the God they worshipped. For this reason, neither religion could completely eradicate the other.

Reading: Anne Askew (A Selection)

from Anne Askew’s First Examination of Anne Askew (1546)

To satisfy your expectation, good people (sayeth she), this was my first examination in the year of our Lord 1545, and in the month of March. First Christopher Dare examined me at Saddlers’ Hall, being one of the quest,1 and asked if I did not believe that the sacrament hanging over the altar was the very body of Christ really. Then I demanded this question of him: wherefore Saint Stephen was stoned to death. And he said he could not tell. Then I answered that no more would I assoil his vain question….

Thirdly, he asked me wherefore I said that I had rather to read five lines in the Bible, than to hear five masses in the temple. I confessed that I said no less. Not for the dispraise of either the Epistle or Gospel, but because the one did greatly edify me, and the other nothing at all. …

Fourthly, he laid unto my charge that I should say: “If an ill priest ministered, it was the Devil and not God.” My answer was that I never spake such thing. But this was my saying: “That whatsoever he were which ministered unto me, his ill conditions could not hurt my faith, but in spirit I received nevertheless the body and blood of Christ.” He asked me what I said concerning confession. I answered him my meaning, which was as Saint James sayeth, that every man ought to knowledge his faults to other, and the one to pray for the other. …

Seventhly, he asked me if I had the spirit of God in me. I answered if I had not, I was but reprobate or cast away. Then he said he had sent for a priest to examine me, which was there at hand. The priest asked me what I said to the sacrament of the altar. And required much to know therein my meaning. But I desired him again to hold me excused concerning that matter. None other answer would I make him, because I perceived him a papist.

Eighthly, he asked me if I did not think that private masses did help souls departed. And I said it was great idolatry to believe more in them than in the death which Christ died for us. Then they had me thence unto my Lord Mayor and he examined me, as they had before, and I answered him directly in all things as I answered the quest afore. Besides this my Lord Mayor laid one thing unto my charge which was never spoken of me but of them. And that was whether a mouse eating the host received God or no. This question did I never ask, but indeed they asked it of me, whereunto I made them no answer but smiled. Then the Bishop’s Chancellor rebuked me and said that I was much to blame for uttering the Scriptures. For Saint Paul (he said) forbade women to speak or to talk of the word of God. I answered him that I knew Paul’s meaning as well as he, which is, 1 Corinthians 14, that a woman ought not to speak in the congregation by the way of teaching. And then I asked him how many women he had seen go into the pulpit and preach? He said he never saw none. Then I said, he ought to find no fault in poor women, except they had offended the law. Then my Lord Mayor commanded me toward. I asked him if sureties would not serve me, and he made me short answer, that he would take none.

Then was I had to the Counter, and there remained eleven days, no friend admitted to speak with me. But in the meantime there was a priest sent to me which said that he was commanded of the Bishop to examine me, and to give me good counsel, which he did not. But first he asked me for what cause I was put in the Counter. And I told him I could not tell. Then he said it was great pity that I should be there without cause, and concluded that he was very sorry for me.

Secondly, he said it was told him that I should deny the sacrament of the altar. And I answered him again that, that I had said, I had said. Thirdly, he asked me if I were shriven. I told him so that I might have one of these three, that is to say, Doctor Crome, Sir William, or Huntingdon, I was contented, because I knew them to be men of wisdom. “As for you or any other I will not dispraise, because I know ye not.”…

Fourthly, he asked me if the Host should fall, and a beast did eat it, whether the beast did receive God or no. I answered, “Seeing ye have taken the pains to ask this question I desire you also to assoil it yourself. For I will not do it, because I perceive ye come to tempt me.” And he said it was against the order of schools6 that he which asked the question should answer it. I told him I was but a woman and knew not the course of schools. Fifthly, he asked me if I intended to receive the sacrament at Easter or no. I answered that else I were no Christian woman, and there I did rejoice, that the time was so near at hand. And then he departed thence with many fair words. …

In the meanwhile he commanded his archdeacon to common with me, who said unto me, “Mistress, where- fore are ye accused and thus troubled here before the Bishop?”

To whom I answered again and said, “Sir, ask, I pray you, my accusers, for I know not as yet.”

Then took he my book out of my hand and said, “Such books as this hath brought you to the trouble you are in. Beware,” sayeth he, “beware, for he that made this book and was the author thereof was an heretic, I warrant you, and burnt in Smithfield.”

Then I asked him if he were certain and sure that it was true that he had spoken. And he said he knew well the book was of John Frith’s8 making. Then I asked him if he were not ashamed for to judge of the book before he saw it within or yet knew the truth thereof. I said also that such unadvised and hasty judgment is token apparent of a very slender wit. Then I opened the book and showed it to him. He said he thought it had been another, for he could find no fault therein. Then I desired him no more to be so unadvisedly rash and swift in judgment, till he thoroughly knew the truth, and so he departed from me.

from John Foxe, Acts and Monuments of these Latter and Perilous Days (1583)

Hitherto we have entreated of this good woman, now it remaineth that we touch somewhat as touching her end and martyrdom. She being born of such stock and kindred that she might have lived in great wealth and prosperity, if she would rather have followed the world than Christ, but now she was so tormented, that she could neither live long in so great distress, neither yet by the adversaries be suffered to die in secret. Wherefore the day of her execution was appointed, and she brought into Smithfield in a chair, because she could not go on her feet, by means of her great torments. When she was brought unto the stake she was tied by the middle with a chain that held up her body. When all things were thus prepared to the fire, the King’s letters of pardon were brought, whereby to offer her safeguard of her life if she would recant, which she would neither receive, neither yet vouchsafe once to look upon. Shaxton1 also was there present who, openly that day recanting his opinions, went about with a long oration to cause her also to turn, against whom she stoutly resisted. Thus she being troubled so many manner of ways, and having passed through so many torments, having now ended the long course of her agonies, being compassed in with flames of fire, as a blessed sacrifice unto God, she slept in the Lord, in anno2 1546, leaving behind her a singular example of Christian constancy for all men to follow.

“I Am a Woman Poor and Blind” (16th century)

I am a woman poor and blind

and little knowledge remains in me,

Long have I sought, but fain would I find,

what herb in my garden were best to be.

A garden I have which is unknown,

which God of his goodness gave to me,

I mean my body, wherein I should have sown

the seed of Christ’s true verity.

My spirit within me is vexed sore,

my flesh striveth against the same:

My sorrows do increase more and more,

my conscience suffereth most bitter pain:

I, with myself being thus at strife,

would fain have been at rest,

Musing and studying in mortal life,

what things I might do to please God best.

With whole intent and one accord,

unto a Gardenthat I did know,

I desired him for the love of the Lord,

true seeds in my garden for to sow.

Then this proud Gardener seeing me so blind,

he thought on me to work his will,

And flattered me with words so kind,

to have me continue in my blindness still.

He fed me then with lies and mocks,

for venial sins he bid me go

To give my money to stones and stocks,

which was stark lies and nothing so.

With stinking meat then was I fed,

for to keep me from my salvation,

I had trentals of mass, and bulls of lead,

not one word spoken of Christ’s passion.

In me was sown all kind of feigned seeds,

with Popish ceremonies many a one,

Masses of requiem with other juggling deeds,

till God’s spirit out of my garden was gone.

Then was I commanded most strictly,

If of my salvation I would be sure,

To build some chapel or chantry,

to be prayed for while the world doth endure.

‘Beware of a new learning,’ quoth he, ‘it lies,

which is the thing I most abhor,

Meddle not with it in any manner of wise,

but do as your fathers have done before.’

My trust I did put in the Devil’s works,

thinking sufficient my soul to save,

Being worse then either Jews or Turks,

thus Christ of his merits I did deprave.

I might liken my self with a woeful heart,

unto the dumb man in Luke the Eleven,

From whence Christ caused the Devil to depart,

but shortly after he took the other seven.

My time thus, good Lord, so wickedly spent,

alas, I shall die the sooner therefore.

Oh Lord, I find it written in thy Testament,

that thou hast mercy enough in store

For such sinners, as the scripture sayeth,

that would gladly repent and follow thy word,

Which I’ll not deny whilst I have breath,

for prison, fire, *****, or fierce sword.

Strengthen me good Lord in thy truth to stand,

for the bloody butchers have me at their will,

With their slaughter knives ready drawn in their hand

my simple carcass to devour and kill.

O Lord forgive me mine offense,

for I have offended thee very sore,

Take therefore my sinful body from hence,

Then shall I, vile creature, offend thee no more.

I would with all creatures and faithful friends

for to keep them from this Gardener’s hands,

For he will bring them soon unto their ends,

with cruel torments of fierce firebrands.

I dare not presume for him to pray,

because the truth of him it was well known,

But since that time he hath gone astray,

and much pestilent seed abroad he hath sown.

Because that now I have no space,

the cause of my death truly to show,

I trust hereafter that by God’s holy grace,

that all faithful men shall plainly know.

To thee O Lord I bequeath my spirit,

that art the work-master of the same,

It is thine, Lord, therefore take it of right,

my carcass on earth I leave, from whence it came.

Although to ashes it be now burned,

I know thou canst raise it again,

In the same likeness as thou it formed,

in heaven with thee evermore to remain.

Reading: From Thomas Cranmer’s The Book of Common Prayer (1552)

Conducting church in English, rather than Latin, required a gifted writer to rework the liturgical service. Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), the Archbishop of Canterbury under Edward VI, was charged with this task in 1549; his earliest edition was a careful re-work of the existing Latin service and represents an uneasy compromise between Catholic and Protestant desires. He revisited the task in 1552, and changed the wording to assert a decidedly Protestant worldview. When Mary I ascended to the throne he was executed, but his Book of Common Prayer was restored under Elizabeth I and remains the basis of Anglican worship to this day. As such, it had a profound influence on English literature and language. The excerpt below details part of the marriage and burial service as it would have been conducted in Elizabethan times.

Dearly beloved friends, we are gathered together here in the sight of God, and in the face of His congregation, to join together this man and this woman in holy matrimony, which is an honorable estate, instituted of God in Paradise, in the time of man’s innocency, signifying unto us the mystical union that is betwixt Christ and His Church: which holy estate Christ adorned and beautified with his presence, and first miracle that He wrought, in Cana of Galilee, and is commended of Saint Paul to be honourable among all men; and therefore is not to be enterprised, nor taken in hand unadvisedly, lightly, or wantonly, to satisfy men’s carnal lusts and appetites, like brute beasts that have no understanding: but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly, and in the fear of God: duly considering the causes for which Matrimony was ordained. One was the procreation of children, to be brought up in the fear and nurture of the Lord, and praise of God. Secondly it was ordained for a remedy against sin, and to avoid fornication, that such persons as have not the gift of continency might marry, and keep themselves undefiled members of Christ’s body. Thirdly, for the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity; into the which holy estate these two persons present come now to be joined. Therefore if any man can show any just cause, why they may not lawfully be joined together: let him now speak, or else hereafter for ever hold his peace. …

If no impediment be alleged, then shall the Curate say unto the man,

Name, Wilt thou have this woman to thy wedded wife, to live together after God’s ordinance in the holy estate of matrimony? Wilt thou love her, comfort her, honour, and keep her in sickness and in health? And forsaking all other keep thee only to her, so long as you both shall live?

The man shall answer,

I will.

Then shall the Priest say to the woman,

Name, Wilt thou have this man to thy wedded husband, to live together after God’s ordinance, in the holy estate of matrimony? Wilt thou obey him, and serve him, love, honor, and keep him, in sickness and in health? and forsaking all other keep the e only unto him , so long as you both shall live?

The woman shall answer,

I will.

Then shall the Minister say,

Who giveth this woman to be married unto this man?

And the Minister receiving the woman at her father or friend’s hands, shall cause the man to take the woman by the right hand, and so either to give their troth to other. The man first saying,

I Name take thee Name to my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health, to love, and to cherish, till death us depart, according to God’s holy ordinance: And thereto I plight thee my troth.

Then shall they loose their hands, and the woman taking again the man by the right hand shall say,

I Name take thee Name to my wedded husband, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health, to love, cherish, and to obey, till death us depart, according to God’s holy ordinance: And thereto I give thee my troth.

Then shall they again loose their hands, and the man shall give unto the woman a ring, laying the same upon the book, with the accustomed duty to the priest and clerk. And the priest taking the ring shall deliver it unto the man, to put it upon the fourth finger of the woman’s left hand. And the man taught by the priest, shall say,

With this ring I thee wed: with my body I thee worship: and with all my worldly goods I thee endow. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Then the man leaving the ring upon the fourth finger of the woman’s left hand, the Minister shall say,

Let us pray.

O Eternal God, Creator and Preserver of all mankind, Giver of all spiritual grace, the Author of everlasting life: Send Thy blessing upon these Thy servants, this man and this woman, whom we bless in Thy name, that as Isaac and Rebecca lived faithfully together; so these persons may surely perform and keep the vow and covenant betwixt them made, whereof this ring given and received is a token and pledge: and may ever remain in perfect love and peace together; and live according unto Thy laws; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Then shall the Priest join their right hands together, and say,

Those whom God hath joined together, let no man put asunder.

“Order for the Burial of the Dead” (1552)

The Priest meeting the corpse at the Church stile, shall say, Or else the priests and clerks shall sing, and so go either unto the church or towards the grave,

I am the Resurrection and the Life (sayeth the Lord): he that believeth in Me, yea though he were dead, yet shall he live. And whosoever liveth and believeth in Me, shall not die for ever. (John 11.)

I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that I shall rise out of the earth in the last day, and shall be covered again with my skin, and shall see God in my flesh: yea, and I my self shall behold Him, not with other but with these same eyes. (Job 19.)

We brought nothing into this world, neither may we carry any thing out of this world. 1 Tim. 6. The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away. Even as it hath pleased the Lord, so cometh things to pass: blessed be the name of the Lord. (Job 1.)

When they come at the grave, whiles the corpse is made ready to be laid into the earth, the Priest shall say, or the priest and clerks shall singe,

Man that is born of a woman, hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery: he cometh up and is cut down like a flower; he flieth as it were a shadow, and never continueth in one stay. (Job 9.) In the midst of life we be in death: of whom may we seek for succour, but of Thee, O Lord, which for our sins justly art displeased? yet, O Lord God most holy, O Lord most mighty, O holy and most merciful Saviour, deliver us not into the bitter pains of eternal death. Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts: shut not up Thy merciful eyes to our prayers: But spare us, Lord most holy, O God most mightie, O holy and merciful Saviour, Thou most worthy judge eternal, suffer us not at our last hour for any pains of death to fall from Thee.

Then while the earth shall be cast upon the body, by some standing by, the priest shall say,

Forasmuch as it hath pleased almighty God of His great mercy to take unto Himself the soul of our dear brother here departed: we therefore commit his body to the ground, earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust, in sure and certain hope of resurrection to eternal life, through our Lord Jesus Christ, who shall change our vile body, that it may be like to His glorious body, according to the mighty working whereby He is able to subdue all things to himself.

Then shall be said or sung,

I heard a voice from heaven, saying unto me: Write from henceforth, blessed are the dead which die in the Lord. Even so sayth the spirit, that they rest from their labours. (Job 11.) …

The Collect

O Merciful God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is the resurrection and the life, in whom whosoever believeth, shall live though he die; and whosoever liveth and believeth in Him, shall not die eternally: who also taught us (by His holy Apostle Paul) not to be sorry, as men without hope, for them that sleep in Him: We meekly beseech Thee (O Father) to raise us from the death of sin unto the life of righteousness, that when we shall depart this life, we may rest in Him, as our hope is this our brother doeth; and that at the general resurrection in the last day, we may be found acceptable in Thy sight, and receive that blessing which Thy well-beloved Son shall then pronounce to all that love and fear Thee, saying: Come, ye blessed children of My Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you from the beginning of the world. Grant this we beseech Thee, O merciful Father, through Jesus Christ our mediator and redeemer. Amen.

Reading: From John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments of these Perilous Times (1563)

King Henry by Parliament according to God’s word put down the Pope: the clergy consented, and all men openly by oath refused this usurped supremacy, knowing by God’s Word Christ to be Head of the Church, and every king in his realm to have under and next unto Christ, the chief sovereignty. King Edward also by Parliament according to God’s Word, set the marriage of priests at liberty, abolished the popish and idolatrous Mass, changed the Latin service, and set up the holy Communion: the whole clergy consented hereunto: many of them set it forth by their preaching: and all they by practicing confirmed the same.

Notwithstanding, now when the state is altered, and the laws changed, the Papistical clergy, with other, like worldlings, as men neither fearing God, neither fleeing worldly shame, neither yet regarding their consciences, oaths, or honesty, like wavering weathercocks, turn round about, and putting on harlots’ foreheads, sing a new song, and cry with an impudent mouth: come again, come again to the Catholic Church, meaning the anti-Christian Church of Rome which is the synagogue of Satan, and the very sink of all superstition, heresy, and idolatry….

The Apostles were beaten for their boldness, and they rejoiced that they suffered for Christ’s cause. Ye have also provided rods for us, and bloody whips: yet when ye have done that which God’s hand and counsel hath determined that ye shall do, be it life or death, I trust that God will so assist us by His holy spirit, and grace, that we shall patiently suffer it, and praise God for it.

“The Benefit and Invention of Printing” from Acts and Monuments (added in1570)

In following the course and order of years, we find this foresaid Year of Our Lord 1450 to be famous and memorable, for the divine and miraculous invention of printing…. The first inventor thereof (as most agree) is thought to be a German dwelling first in Strasbourg, afterward citizen of Mainz, named John Faustus, a goldsmith. The occasion of this invention first was by engraving the letters of the alphabet in metal: who then laying black ink upon the metal, gave the form of the letters in paper. The man being industrious and active perceiving that, thought to proceed further, and to prove whether it would frame as well in words and in whole sentences as it did in letters. Which when he perceived to come well to pass, he made certain other of his counsel, one John Gutenberg and Peter Schaeffer, binding them by their oath to keep silence for a season. After 10 years, John Gutenberg, copartner with Faustus, began then first to broach the matter at Strasbourg. The Art being yet but rude, in process of time was set forward by inventive wits, adding more and more to the perfection thereof….

Printing came of God. Notwithstanding what man soever was the instrument, without all doubt God Himself was the ordainer and disposer thereof. … Now to consider to what end and purpose the Lord hath given this gift of printing to the earth, and to what great utility and necessity it serveth, it is not hard to judge…. God of His secret judgement, seeing time to help His church, hath found a way by this faculty of printing, not only to confound his1 life and conversation, which before he could not abide to be touched, but also to cast down the foundation of his standing, that is, to examine, confute, and detect his doctrine, laws, and institution most detestable, in such sort, that though his life were never so pure: yet his doctrine standing, as it doth, no man is so blind, but may see, that either the Pope is Antichrist, or else that Antichrist is near cousin to the Pope: And all this doth, and will hereafter more and more appear, by printing.

The reason whereof is this: for that hereby tongues are known, knowledge groweth, judgement increaseth, books are dispersed, the Scripture is seen, the doctors be read, stories be opened, times compared, truth discerned, falsehood detected, and with finger pointed, and all (as I said) through the benefit of printing. Wherefore I suppose that either the Pope must abolish printing, or he must seek a new world to reign over: for else, as this world standeth, printing, doubtless, will abolish him. Both the Pope, and all his College of Cardinals, must this understand, that through the light of printing, the world beginneth now to have eyes to see, and heads to judge. He can not walk so invisible in a net, but he will be spied…. So that either the Pope must abolish knowledge and printing, or printing at length will root him out. By reason whereof, as printing of books ministered matter of reading: so reading brought learning: learning showed light, by the brightness whereof blind ignorance was suppressed, error detected, and finally God’s glory, with truth of His word, advanced.

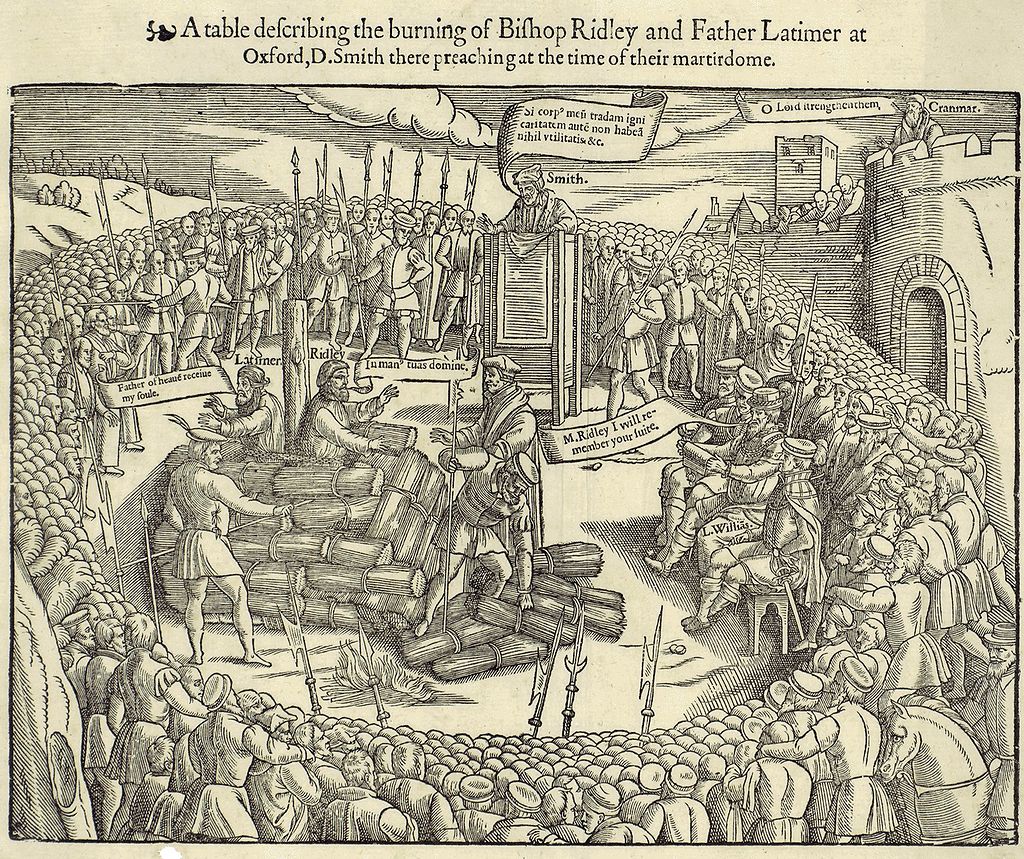

“Bishop Ridley and Bishop Lattimer” from Acts and Monuments

These reverend prelates suffered October 17, 1555, at Oxford, on the same day Wolsey and Pygott perished at Ely. Pillars of the Church and accomplished ornaments of human nature, they were the admiration of the realm, amiably conspicuous in their lives, and glorious in their deaths.

Dr. Ridley was born in Northumberland, was first taught grammar at Newcastle, and afterward removed to Cambridge, where his aptitude in education raised him gradually until he came to be the head of Pembroke College, where he received the title of Doctor of Divinity. Having returned from a trip to Paris, he was appointed chaplain by Henry VIII and Bishop of Rochester, and was afterwards translated to the see of London in the time of Edward VI.

To his sermons the people resorted, swarming about him like bees, coveting the sweet flowers and wholesome juice of the fruitful doctrine, which he did not only preach, but showed the same by his life, as a glittering lantern to the eyes and senses of the blind, in such pure order that his very enemies could not reprove him in any one jot. …

Dr. Ridley was first in part converted by reading Bertram’s book on the Sacrament, and by his conferences with Archbishop Cranmer and Peter Martyr.

When Edward VI was removed from the throne, and the bloody Mary succeeded, Bishop Ridley was immediately marked as an object of slaughter. He was first sent to the Tower, and afterward, at Oxford, was consigned to the common prison of Bocardo, with Archbishop Cranmer and Mr. Latimer. Being separated from them, he was placed in the house of one Irish, where he remained until the day of his martyrdom, from 1554, until October 16, 1555. …

This old practiced soldier of Christ, Master Hugh Latimer, was the son of one Hugh Latimer, of Thurkesson in the county of Leicester, a husbandman, of a good and wealthy estimation; where also he was born and brought up until he was four years of age, or thereabout: at which time his parents, having him as then left for their only son, with six daughters, seeing his ready, prompt, and sharp wit, purposed to train him up in erudition, and knowledge of good literature; wherein he so profited in his youth at the common schools of his own country, that at the age of fourteen years, he was sent to the University of Cambridge; where he entered into the study of the school divinity of that day, and was from principle a zealous observer of the Romish superstitions of the time. In his oration when he commenced bachelor of divinity, he inveighed against the reformer Melanchthon,1 and openly declaimed against good Mr. Stafford, divinity lecturer in Cambridge.

Mr. Thomas Bilney, moved by a brotherly pity towards Mr. Latimer, begged to wait upon him in his study, and to explain to him the groundwork of his (Mr. Bilney’s) faith. This blessed interview effected his conversion: the persecutor of Christ became his zealous advocate, and before Dr. Stafford died he became reconciled to him.

Once converted, he became eager for the conversion of others, and commenced to be public preacher, and private instructor in the university. His sermons were so pointed against the absurdity of praying in the Latin tongue, and withholding the oracles of salvation from the people who were to be saved by belief in them, that he drew upon himself the pulpit animadversions of several of the resident friars and heads of houses, whom he subsequently silenced by his severe criticisms and eloquent arguments. This was at Christmas, 1529. At length Dr. West preached against Mr. Latimer at Barwell Abbey, and prohibited him from preaching again in the churches of the university, notwithstanding which, he continued during three years to advocate openly the cause of Christ, and even his enemies confessed the power of those talents he possessed. Mr. Bilney remained here some time with Mr. Latimer, and thus the place where they frequently walked together obtained the name of Heretics’ Hill.

Mr. Latimer at this time traced out the innocence of a poor woman, accused by her husband of the murder of her child. Having preached before King Henry VIII at Windsor, he obtained the unfortunate mother’s pardon.

This, with many other benevolent acts, served only to excite the spleen of his adversaries. He was summoned before Cardinal Wolsey for heresy, but being a strenuous supporter of the King’s supremacy, in opposition to the Pope’s, by favor of Lord Cromwell and Dr. Buts (the king’s physician), he obtained the living of West Kingston, in Wiltshire. For his sermons here against Purgatory, the immaculacy of the Virgin, and the worship of images, he was cited to appear before Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, and John, Bishop of London. He was required to subscribe certain articles, expressive of his conformity to the accustomed usages; and there is reason to think, after repeated weekly examinations, that he did subscribe, as they did not seem to involve any important article of belief.

Guided by Providence, he escaped the subtle nets of his persecutors, and at length, through the powerful friends before mentioned, became Bishop of Worcester, in which function he qualified or explained away most of the papal ceremonies he was for form’s sake under the necessity of complying with. He continued in this active and dignified employment some years.

Beginning afresh to set forth his plow he labored in the Lord’s harvest most fruitfully, discharging his talent as well in diverse places of this realm, as before the King at the court. In the same place of the inward garden, which was before applied to lascivious and courtly pastimes, there he dispensed the fruitful Word of the glorious Gospel of Jesus Christ, preaching there before the King and his whole court, to the edification of many….

By the strength of his own mind, or of some inward light from above, he had a prophetic view of what was to happen to the Church in Mary’s reign, asserting that he was doomed to suffer for the truth … Soon after Queen Mary was proclaimed, a messenger was sent to summon Mr. Latimer to town, and there is reason to believe it was wished that he should make his escape.

Thus Master Latimer coming up to London, through Smithfield (where merrily he said that Smithfield had long groaned for him), was brought before the Council, where he patiently bore all the mocks and taunts given him by the scornful papists. He was cast into the Tower, where he, being assisted with the heavenly grace of Christ, sustained imprisonment a long time, notwithstanding the cruel and unmerciful handling of the lordly papists, which thought then their kingdom would never fall; he showed himself not only patient, but also cheerful in and above all that which they could or would work against him. Yea, such a valiant spirit the Lord gave him, that he was able not only to despise the terribleness of prisons and torments, but also to laugh to scorn the doings of his enemies.

Mr. Latimer, after remaining a long time in the Tower, was transported to Oxford, with Cranmer and Ridley, the disputations at which place have been already mentioned in a former part of this work. He remained imprisoned until October, and the principal objects of all his prayers were three—that he might stand faithful to the doctrine he had professed, that God would restore His Gospel to England once again, and preserve the Lady Elizabeth to be queen; all of which happened. When he stood at the stake without the Bocardo gate,1 Oxford, with Dr. Ridley, and fire was putting to the pile of faggots, he raised his eyes benignantly towards heaven, and said, “God is faithful, who will not suffer you to be tempted above that ye are able.” His body was forcibly penetrated by the fire, and the blood flowed abundantly from the heart; as if to verify his constant desire that his heart’s blood might be shed in defence of the Gospel. His polemical and friendly letters are lasting monuments of his integrity and talents. It has been before said, that public disputation took place in April, 1554, new examinations took place in October, 1555, previous to the degrada- tion and condemnation of Cranmer, Ridley, and Latimer. We now draw to the conclusion of the lives of the two last.

Dr. Ridley, the night before execution, was very facetious, had himself shaved, and called his supper a marriage feast; he remarked upon seeing Mrs. Irish (the keeper’s wife) weep, “Though my breakfast will be somewhat sharp, my supper will be more pleasant and sweet.”

The place of death was on the north side of the town, opposite Balliol College. Dr. Ridley was dressed in a black gown furred, and Mr. Latimer had a long shroud on, hanging down to his feet. Dr. Ridley, as he passed Bocardo, looked up to see Dr. Cranmer, but the latter was then engaged in disputation with a friar. When they came to the stake, Mr. Ridley embraced Latimer fervently, and bid him: “Be of good heart, brother, for God will either assuage the fury of the flame, or else strengthen us to abide it.” He then knelt by the stake, and after earnestly praying together, they had a short private conversation. Dr. Smith then preached a short sermon against the martyrs, who would have answered him, but were prevented by Dr. Marshal, the vice-chancellor. Dr. Ridley then took off his gown and tippet, and gave them to his brother-in-law, Mr. Shipside. He gave away also many trifles to his weeping friends, and the populace were anxious to get even a fragment of his garments. Mr. Latimer gave nothing, and from the poverty of his garb, was soon stripped to his shroud, and stood venerable and erect, fearless of death.

Dr. Ridley being unclothed to his shirt, the smith placed an iron chain about their waists, and Dr. Ridley bid him fasten it securely; his brother having tied a bag of gunpowder about his neck, gave some also to Mr. Latimer.

Dr. Ridley then requested of Lord Williams, of Fame, to advocate with the Queen the cause of some poor men to whom he had, when bishop, granted leases, but which the present bishop refused to confirm. A lighted faggot was now laid at Dr. Ridley’s feet, which caused Mr. Latimer to say: “Be of good cheer, Ridley; and play the man. We shall this day, by God’s grace, light up such a candle in England, as I trust, will never be put out.”

When Dr. Ridley saw the fire flaming up towards him, he cried with a wonderful loud voice, “Lord, Lord, receive my spirit.” Master Latimer, crying as vehemently on the other side, “Father of heaven, receive my soul!” received the flame as it were embracing of it. After that he had stroked his face with his hands, and as it were, bathed them a little in the fire, he soon died (as it appeareth) with very little pain or none.

Well! dead they are, and the reward of this world they have already. What reward remaineth for them in heaven, the day of the Lord’s glory, when He cometh with His saints, shall declare.

In the following month died Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor of England.

This papistical monster was born at Bury, in Suffolk, and partly educated at Cambridge. Ambitious, cruel, and bigoted, he served any cause; he first espoused the King’s part in the affair of Anne Boleyn: upon the establishment of the Reformation he declared the supremacy of the Pope an execrable tenet; and when Queen Mary came to the crown, he entered into all her papistical bigoted views, and became a second time Bishop of Winchester. It is conjectured it was his intention to have moved the sacrifice of Lady Elizabeth, but when he arrived at this point, it pleased God to remove him.

It was on the afternoon of the day when those faithful soldiers of Christ, Ridley and Latimer, perished, that Gardiner sat down with a joyful heart to dinner. Scarcely had he taken a few mouthfuls, when he was seized with illness, and carried to his bed, where he lingered fifteen days in great torment, unable in any wise to evacuate, and burnt with a devouring fever, that terminated in death. Execrated by all good Christians, we pray the Father of mercies, that he may receive that mercy above he never imparted below.

Reading: From Lady Margaret Hoby’s Diaries (1599-1603)

1599

Friday, August 17

After private prayers I went about the house and read of the Bible and wrought till dinner time: and after dinner it pleased for a just punishment to correct my sins to send me feebleness of stomach and pain of my head that kept me upon my bed till five o’clock: at which time I arose, having release of my sickness, according to the wonted kindness of the Lord who after He had let me see how I had offended, that so I might take better heed to my body and soul hereafter, with a gentle correction let me feel He was reconciled to me: at which time I went to private prayer and praises, exami- nation, and so to work till supper time: which done I heard the lecture and after I had walked an hour with Mr. Hoby I went to bed.

Monday, September 10

After private prayers I went about the house, and then ate my breakfast: then I walked to the church with Mr. Hoby: after that I wrought a little and neglected my custom of prayer for which as for many other sins it pleased the Lord to punish me with an inward assault: But I know the Lord hath pardoned it because He is true of His promise, and if I had not taken this course of examination I think I had forgotten it: after dinner I walked with Mr. Hoby and after he was gone I went to get tithe apples:2 after I came home, I prayed with Mr. Rhodes,3 and after that privately by myself and took examination of myself: and so after I had walked a while I went to supper, after that to the lecture and so to bed.

The Lord’s Day, September 16

After I had prayed privately I went to church and from thence returning I praised God both for the enabling the minister so profitably to declare the word as he had, and my self to hear with that comfort and understand- ing I did: after dinner I walked with Mr. Hoby till catechizing was done and then I went to church: after the sermon I looked upon a poor man’s leg4 and after that I walked and read a sermon of Gifford upon the Song of Solomon: then I examined myself and prayed: after supper I was busy with Mr. Hoby till prayer time after which I went to bed.

Thursday, December 20

After private prayers, I did eat my breakfast then I writ in my sermon book: after I prayed then I dined, and almost I writ in my Bible all the afternoon: then I dispatched some business in the house and then prayed and examined myself …

1600

The 5 day of the week, February 1

After I was ready I went about the house and then prayed, brake my fast, dressed a poor boy’s leg that was hurt, and Jurden’s5 hand: after took a lecture, read of the Bible, prayed and so went to dinner: after, I went down a while, then wrought till four o’clock and took order for supper, and then talked a while with Mr. Hoby and after went to private prayer and meditation: after to supper then to public prayers and lastly to bed.

The 4 day after the Lord’s Day, April 10

After private prayers I went to the minister where I heard Mr. Smith defend the truth against the papist: The question being whether the regenerate do sin: after I came home I went to dinner: I went to the church where I heard Mr. Stuart handle this question between the papists and us—whether we were justified by faith or work:1 after I came to my lodging and after I had prayed I went and talked with my cousin Bouser: then I went to Mr. Doctor Benet’s and after supper I prayed publicly with Mr. Rhodes, and so went to bed.

1601

The 5 day of May 1601

After prayers I went to the church where I heard a sermon: after I came home and heard Mr. Rhodes read: after dinner I went abroad and when I was come home I dressed some sores: after I heard Mr. Rhodes read and wrought within a while: after I went to see a calf at Munckman’s which had two great heads, four ears, and had to either head a throat pipe besides: the heads had long hairs like bristles about the mouths, such as no other cow hath: the hinder legs had no parting from the rump, but grew backward, and were no longer but from the first joint: also the back bone was parted about the middest of the back, and a round hole was in the midst in to the body of the calf: but one would have thought that to have come of some stroke it might get in the cow’s belly: after this I came in to private meditation and prayer.

August 26

This day in the afternoon I had had a child brought to see that was born at Silpho, one Talliour’s son who had no fundament, and had no passage for excrements but at the mouth: I was earnestly entreated to cut the place to see if any passage could be made, but although I cut deep and searched there was none to be found.

December 26

Was young Farley slain by his father’s man one that the young man had before threatened to kill and for that end prosecuting him: the man, having a pike staff in his hand, run him into the eye and so into the brain: he never spoke after: this judgment is worth noting, this young man being extraordinary profane, as once causing a horse to be brought into the church of God and there christening him with a name which horrible blasphemy the Lord did not leave unrevenged, even in this world, for example t’oth ers.

1602

May 6

I praise God I had health of body: howsoever justly God hath suffered Satan to afflict my mind, yet my hope is that my Redeemer will bring my soul out of troubles, that it may praise His name: and so I will wait with patience for deliverance.

The Lord’s Day, June 27

Until this day I have continued in bodily health not- withstanding Satan hath not ceased to cast his malice upon me: but temptations hath exercised me, and it hath pleased my God to deliver me from all: Mrs. Girl- ington with her daughter and son-in-law came but after the sermon: and so, when the Communion was ended and after dinner, we all heard the afternoon exercises2 together.

1603

March 26

This day being the Lord’s Day was the death of the Queen published and our now King James of Scotland proclaimed King to succeed her: God send him a long and happy reign, Amen.

October 23

This day I heard the plague was so great at Whitby that those which were clear shut themselves up, and the infected that escaped did go abroad: likewise it was reported that, at London, the number was taken of the living and not of the dead: Lord grant that these judgments may cause England with speed to turn to the Lord.

Reading: From Owen Feltham, Resolves (1623)

I find many that are called Puritans; yet few, or none that will own the name. Whereof the reason sure is this; that ’tis for the most part held a name of infamy; and is so new, that it hath scarcely yet obtained a definition: nor is it an appellation derived from one man’s name, whose tenets we may find, digested into a volume: whereby we do much err in the application. It imports a kind of excellency above another; which man (being conscious of his own frail bendings) is ashamed to assume to himself. So that I believe there are men which would be Puritans: but indeed not any that are. One will have him one that lives religiously, and will not revel it in a shoreless excess. Another, him that separates from our divine assemblies. Another, him that in some tenets only is peculiar. Another, him that will not swear. Absolutely to define him is a work, I think, of difficulty; some I know that rejoice in the name; but sure they be such, as least understand it. As he is more generally in these times taken, I suppose we may call him a Church-rebel, or one that would exclude order, that his brain might rule. To decline offences; to be careful and conscionable in our several actions, is a purity that every man ought to labour for, which we may well do, without a sullen segregation from all society. … If mirth and recreations be lawful, sure such a one may lawfully use it. If wine were given to cheer the heart, why should I fear to use it for that end? Surely, the merry soul is freer from intended mischief, than the thoughtful man. A bounded mirth, is a patent adding time and happiness to the crazed life of man. … God delights in nothing more than in a cheerful heart, careful to perform him service. What parent is it, that rejoiceth not to see his child pleasant, in the limits of a filial duty? I know, we read of Christ’s weeping, not of his laughter: yet we see, he graceth a feast with his first miracle; and that a feast of joy: And can we think that such a meeting could pass without the noise of laughter? What a lump of quickened care is the melancholic man! Change anger into mirth, and the precept will hold good still: Be merry, but sin not. As there be many, that in their life assume too great a liberty; so I believe there are some, that abridge themselves of what they might lawfully use. Ignorance is an ill steward, to provide for either soul, or body. A man that submits to reverent order, that sometimes unbends himself in a moderate relaxation; and in all, labours to approve himself, in the sereneness of a healthful conscience: such a Puritan I will love immutably. But when a man, in things but ceremonial, shall spurn at the grave authority of the Church, and … out of a blind and uncharitable pride, censure and scorn others as reprobates: or out of obstinacy, fill the world with brawls about undeterminable tenets: I shall think him one of those, whose opinion hath fevered his zeal to madness and distraction. I have more faith in one Solomon, than in a thousand Dutch parlours of such opinionists. Behold then, what I have seen good! That it is comely to eat, and to drink, and to take pleasure in all his labour wherein he travaileth under the sun, the whole number of the days of his life, which God giveth him. For, this is his portion. Nay, “there is no profit to man, but that he eat, and drink, and delight his soul with the profit of his labour.” For, he that saw other things but vanity, saw this also, that it was the hand of God. Me thinks the reading of Ecclesiastes, should make a Puritan undress his brain, and lay off all those fanatic toys that jingle about his understanding. For my own part, I think the world hath not better men, than some that suffer under that name: nor withal, more scelestic villainies. For, when they are once elated with that pride, they so contemn others, that they infringe the laws of all human society.

Reading: Jews and Christians (A Selection)

from Richard Morison, A Remedy for Sedition (1536)

… I have oft marvelled, to see the diligence, that the Jews use in bringing up their youth, and been much ashamed to see how negligent Christian men are in so godly a thing. There is neither man, woman, nor child of any lawful age, but he for the most part knoweth the Laws of Moses: and with us he is almost a good curate, that knoweth vi. or vii. of the x. Commandments: amongst the Jews, there is not one, but he can by some honest occupation, get his living. There be few idle, none at all, but such as be rich enough, and may live without labour. There is not one beggar amongst them. All the cities of Italy, many places in Cecilia, many burgs in Germany, have a great number of Jews in them. I have been among them, that are in Italy, I never heard of a Jew, that was a thief, never that was a murderer. No I never heard of a fray between them. I am ashamed to say as I needs must say, they may well think their religion better than ours, if religion be tried by men’s lives. Now if Moses’ law learned in youth, and but carnally understand,1 can so stay them, that few or none fall into other vice, than usury, which although they do think permitted by Moses’ law, so they use it not one Jew to another, as indeed they do not, but a Jew to a stranger. Might not we learn so much of Christ’s law, as were able to keep us from rebellion? … It is, it is undoubted, one sort of religion, though also it be not right, that keepeth men in concord and unity. Turks go not against Turks, nor Jews against Jews, because they both agree in their faith. …

from Samuel Usque, Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel (1553)

In the same country I witnessed another fierce and terrible calamity. After that king2 had left this life he was succeeded by another, who disregarded the past expulsion and recalled all the Jews who had left the kingdom, offering to take them back and let them live in peace. The Jews took counsel among themselves in France, Flanders, Spain, and other lands where they had dispersed. They decided that for no reason, including ease or material gain, would they re-enter a place where they had suffered so great a calamity—except to see the children they had left behind, to talk with them and convince them to return to the faith of their fathers. …

O cruel Englishmen, … so quick to hurt me and so blind to the reason for which you harmed me! How is it that you have not become inured to crime from of old? Are not the ways of your princesses adulterous? Is not the garb of your masses woven of robberies, hatreds, and killing? I do not need to cite ancient histories to tell this, for modern records proclaim it. Consider in the years that King Henry reigned, how many acts of adultery were committed by his own queens; how many treacher- ies were attempted by the king’s noblest and closest associates; how many heads were placed on London Bridge because of these and other ghastly crimes; and how many queens were killed by the sword, and de- prived of dominion? The churches where you prayed were demolished by your own hands or converted to stables. Your priests were shamefully expelled.3 …

According to your religion, all these acts, singly and collectively, are regarded as sins. They manifest extreme wickedness, and you deserved punishment for them. Misfortunes did not come to your land because of the Jews’ sins alone, as you say.

from Thomas Lodge, Wit’s Misery, and the World’s Madness (1596)

This Usury [has] the complexion of the baboon his father; he is haired like a great ape, and swart like a tawny Indian … He is narrow-browed, and squirrel- eyed, and the chiefest ornament of his face is, that his nose sticks in the midst like an embossment in terrace work, here and there embellished and decked with verrucae for want of purging with agaric; some authors have compared it to a rutter’s cod-piece, but I like not the allusion so well, by reason the tyings have no correspondence. His mouth is always mumbling, as if he were at his matins: and his beard is bristled here and there like a sow that had the lousy.3 Double-chinned he is, and over his throat hangs a bunch of skin like a money-bag. …

from Edward Coke, The Institutes of the Laws of England, Part 2 (1642)

Many prohibitions were made by this King and others, [and] some time[s] they [the Jews] were banished, but their cruel usury continued, and soon after they returned. And for respect of lucre and gain, King John in the second year of his reign granted unto them large liberties and priveledges, whereby the mischiefs rehearsed in this act without measure multiplied.

Our noble King Edward I and his father King Henry III before him, fought by diverse acts and ordinances to use some mean and moderation herein, but in the end it was found that there was no mean in mischief. … And therefore King Edward I as this act said, in the honour of God, and for the common profit of his people, without all respect (in the respect of these) of the filling of his own coffers, did ordain, that no Jew from thence- forth would make any bargain, or contract for usury, no upon any former contract should take any usury; … so in effect all Jewish usury was forbidden. …

This law struck at the root of the pestilent weed, for hereby usury itself was forbidden; and thereupon the cruel Jews thirsting after wicked gain, to the number of 15,060, departed out of this realm into foreign parts, where they might use their Jewish trade of usury, and from that time that nation never returned again into this realm. …

Source Texts:

Askew, Anne. “An Askew. Intitled, I am a Woman Poor and Blind.” Early English Books Online, University of Michigan, n.d, and is licensed under CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.

![]()

Coke, Edward. The Second Part of the Institutes of Laws of England. E. and R. Brooke, 1797, is licensed under no known copyright.

Cranmer, Thomas. “From the Book of Common Prayer.” The Two Liturgies, A.D. 1549, and A.D. 1552: with other Documents Set Forth by Authority in the Reign of King Edward VI, University of Cambridge Press, 1844, is licensed under no known copyright.

Feltham, Owen. Resolves, Divine Moral and Political. Pickering, 1840, is licensed under no known copyright.

Foxe, John. “From the First Examination of Anne Askew” and “From John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments.” The Unabridged Acts and Monuments Online or TAMO (1576 edition). The Digital Humanities Institute, Sheffield, 2011, is licensed under no known copyright.

Hoby, Margaret. The Private Life of an Elizabethan Lady: The Diary of Lady Margaret Hoby, 1599-1605, ed. by Dorothy Meads. G. Routledge & Sons, 1930, is licensed under no known copyright.

Lodge, Thomas. VVits miserie, and the vvworlds madnesse. University of Michigan, n.d, and is licensed under CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.

![]()

Morison, Richard. A Remedy for Sedition, Early English Books Online, University of Michigan, n.d, and is licensed under CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.

![]()

Usque, Samuel. Consolaçam ás tribulaçoens de Israel, Coimbra, 1906, is licensed under no known copyright.