77 William Shakespeare: Selected Sonnets

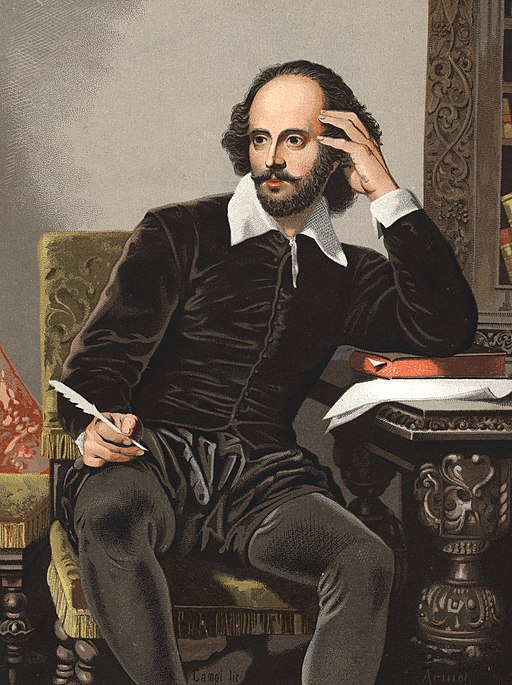

“William Shakespeare” by Batyr Ashirbayev, 2019. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Mikayla Langham, Nicole Almendarez and Kaeli Walls

Biography

Shakespeare, arguably the most world-renowned writer in the English language, is thought to have been born on April 23, 1564 just three days before his official baptism, in Stratford-upon-Avon. He was born to John and Mary Shakespeare, who are both assumed to be illiterate. Though it cannot be verified, experts believe he went to the New Grammar School of Stratford-upon-Avon from the age of 6 to around 13, when his family faced financial hardship and he was likely compelled to leave (Mibillard). From there, speculators say that Shakespeare spent his time working in a butcher shop, as well as helping his dad run his business (Mibillard).

He married his wife, Anne Hathaway, when he was 18 and she 26; at the time, she was already pregnant with their first child, Susanna. They would go on to have twins as well, one of whom—their only boy, Hamnet–died at the age of 11 around the time Shakespeare composed Hamlet, which is one of the only clues we have to the intersection of art and biography in his works.

From 1585 to 1592 there are no records found of Shakespeare. These are considered Shakespeare’s “lost years.” Around the year of 1590, Shakespeare started composing and producing plays, including Henry VI Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Richard III, The Comedy of Errors, etc. By the year 1613, he had written 37 in total. Within those plays there was four main genres: romance (Romeo and Juliet), comedies (As You Like It), tragedies (Hamlet), and histories (King John).

In these plays, he was able to connect with the audience through intense emotions, witty wordplay and themes that connected deeply to the human experience, rather than to the supernatural. By the year 1599, the Globe Theatre was open. The Globe Theatre was where Shakespeare did much of his acting and production, with the King’s Men, perhaps the most well-regarded acting troupe of his generation (“William Shakespeare” Wikipedia). Shakespeare was a part of this company for most of his career, and it was affiliated with the royal court of James I. At this time theatre was considered a treat for only the wealthy, and those who couldn’t afford it could sit outside the theatre or in “the pit” for a penny (Poulter). The year 1609 was when Shakespeare’s sonnets were published by Thomas Thorpe. He began writing them around the year 1585 to 1592, 154 in total. These cover three main themes and are thought to be some of the best love poetry to this day. Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616 and was buried at Stratford Church.

Shakespeare was a common boy, had basic education, and—as far as is known—never ventured abroad. Yet, the knowledge of history, geography and language evident from his plays has led many to question whether “Shakespeare” may have been a pseudonym for another writer (Chadwick). Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon and Amelia Lanyar have been among the most prominent of the nominees for the “true” identity of Shakespeare. It is unlikely that this controversy will ever be resolved; what is known for sure is that Shakespeare’s contribution to English language and letters is without parallel.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets

It is believed that William Shakespeare began writing his sonnets, The Sonnets of Shakespeare, towards the end of his “lost years.” The exact date can’t be known but has been assumed to be between 1592 and 1601. Thomas Thorpe then published them in 1609, but he did so without knowledge of if he was publishing them in the order Shakespeare wrote them, or even if Shakespeare intended them to be published in this order.

A sonnet is a short poem, usually ten to fourteen lines, that uses any of a number of formal rhyme schemes. While there are multiple types of sonnets, and many authors have tried their hand at the genre, some of the most known and beloved are those by William Shakespeare. Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets. The majority of the sonnets, that is, the first 126, are addressed to a young man whom the poet has a romantic, loving relationship with. The first seventeen sonnets are used to try to convince the young man to marry and have beautiful children. The rest of the sonnets in what is known as “the young man sequence” are about the power of poetry, pure love, and defeating death (Mabillard). The remaining sonnets (127-154) are written to the dark lady- a promiscuous and raven-haired temptress, the tone of which is “…distressing, with language of sensual feasting, uncontrollable urges, and sinful consumption” (Mabillard). It is natural for a current reader to read the sonnets in an autobiographical style, but the true nature of the poems is unknown. The sonnets are possibly drawn from personal experiences in William Shakespeare’s life as they are written in a story format, albeit obliquely. It is suggested that they are written to intentionally play with the reader by creating this poet-boy-dark lady love triangle. This style was popular at the time and can also be seen in many Shakespearian comedies and plays (Crawforth). Shakespeare created some of the most fascinating and influential poems ever written, and certainly left his mark on the history of poetry.

Shakespearian Style and Iambic Pentameter

Shakespearean sonnets are written in fourteen lines: “The first twelve lines are divided into three quatrains with four lines each. In the three quatrains the poet establishes a theme or problem and then resolves it in the final two lines, called the couplet” (Mabillard). There is also a standard rhyme scheme and rhythm. The rhyme pattern is: “abab cdcd efef gg.” This sonnet structure is known as the “English sonnet” or the “Shakespearean sonnet,” to distinguish it from six other different rhyming patterns common to the sonnet form. Shakespeare’s sonnets are mostly written in a type of metrical line called “iambic pentameter.” Each sonnet line consists of ten syllables. The syllables are divided into five pairs called “iambs” or “feet.” An iamb is made up of one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable:

Here is an example of a Shakespearian Sonnet line written in Iambic Pentameter:

Shall I / com PARE/ thee TO / a SUM / mer’s DAY?

Thou ART / more LOVE / ly AND / more TEM / per ATE (Sonnet 18)

We believe that Shakespeare may have used Iambic Pentameter because it is easier for actors to memorize and for the audience to understand.

In addition to dramatic metaphors, the use of oxymorons is a common literary device used by William Shakespeare. An oxymoron is a stylistic figure where the coupling of opposing words is used to create an effect (Sakaeva). It is likely that Shakespeare used oxymoron to dramatically illustrate the polarity of events and as a creative writing invention. In sonnet forty Shakespeare uses the oxymoron “Lascivious (Lustful) Grace” to mean refined sensuality. Shakespeare is a master of prose and poetry, which is why he is so highly revered to this day: “Since Homer, no poet has come near Shakespeare in originality, freshness, opulence, and boldness of imagery” (Hudson).

Theories about William Shakespeare and the Shakespearean Sonnet

As stated, we do not know the true nature of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Are they strictly autobiographical? Are some of the Sonnets written vicariously? Or are they completely imaginary, but purposefully written to intrigue and confuse the reader? If they are autobiographical, does this mean that William Shakespeare was homosexual? We will never know for certain, but if Shakespeare’s hope was to open the conversation, he surely succeeded. There is also speculation as to whom his two main subjects (the “Fair Youth” and the “Dark Lady”) may have been modeled on. It is believed that the dark lady is one of three historical women: Mary Fitton, a lady in waiting to Queen Elizabeth; Lucy Morgan, a brothel owner and former maid to Queen Elizabeth; and Emilia Lanier, the mistress of Lord Hunsdon, patron of the arts (Mabillard). A large part of the beauty of these sonnets is the historical mystery that shrouds them.

Works Cited

Chadwick, Bruce. “Who Really Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays?” History News Network, 20 May 2018, historynewsnetwork.org/article/169054. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Crawforth, Hannah. “An Introduction to Shakespeare’s Sonnets.” British Library Online. 13 July 2017. www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/an-introduction-to-shakespeares-sonnets Accessed 04 Nov. 2019.

Hudson, Henry Norman. Shakespeare: His Life, Art, and Characters, Volume I. 1872. Shakespeare Online. www.shakespeare-online.com/biography/imagery.html Accessed 04 Nov. 2019.

Mabillard, Amanda. “Introduction to Shakespeare’s Sonnets.” Shakespeare Online, 30 Aug. 2000. www.shakespeare-online.com/sonnets/sonnetintroduction.html. Accessed 04 Nov. 2019

Poulter, Eliza. “The Seating at The Globe Theatre.” Seating in The Globe Theatre – The Globe Theatre, The Globe Theatre, the-globe-theatre.weebly.com/seating-in-the-globe-theatre.html. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Sakaeva, L. and L. Kornilova. “Structural Analysis of the Oxymoron in the Sonnets of William Shakespeare.” Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 6(5), 409-414.

“William Shakespeare.” Wikipedia. 28 May 2019. Web. 03 June 2019. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Shakespeare. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.

Discussion Questions

- Does the controversy surrounding Shakespeare’s authorship have any bearing on the works themselves? Why/why not?

- What accounts for the lasting appeal of his plays and sonnets?

- Did his complicated and seemingly unfulfilling domestic life influence his works? Should biography be considered in the interpretation of great literature?

- “Love” is a multifaceted term, and Shakespeare explores it in every way throughout his sonnets. Love as friendship, as family, as devotion, as lust, as affection. Are there any other authors you can think of exploring the many forms of love as he does?

- Why do you believe Shakespearian sonnets, comedies, and plays are still so celebrated and revered today?

- The sonnets are considered some of the greatest love poetry ever written – do you agree? Disagree? Why? Why is Sonnet 18 so famous?

- How are Shakespeare’s sonnets related to real life?

- How do the sonnets explore the human spirit in confrontation with love, death, change, and time?

- There are many interpretations of the “Dark Lady.” Let’s assume she is a metaphor. What might she be a metaphor of?

Further Resources

- A video covering the background, rules, and significance of shakespearean sonnets.

- A podcast series that explores Shakespeare’s work, life, and the effect they have on the world.

- Audio Clips of each sonnet broken into sections.

- A two-page “cheat sheet” on analyzing Shakespeare’s sonnets This is a website that shoes you how to analyze Shakespearean sonnet form:

- This website offers side-by-side “translations” of Shakespeare into modern English

- A comprehensive glossary of Shakespeare’s invented words (as found in his plays and poems)

Reading: Selected Sonnets

1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

3

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb,

Of his self-love to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live, remember’d not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

12

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls, all silvered o’er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves,

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard,

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

15

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment,

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky,

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory;

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful Time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

18

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimm’d:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st,

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

19

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood;

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws,

And burn the long-liv’d phoenix, in her blood;

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleets,

And do whate’er thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one most heinous crime:

O! carve not with thy hours my love’s fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen;

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men.

Yet, do thy worst old Time: despite thy wrong,

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion:

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue all ‘hues’ in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

23

As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put beside his part,

Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage,

Whose strength’s abundance weakens his own heart;

So I, for fear of trust, forget to say

The perfect ceremony of love’s rite,

And in mine own love’s strength seem to decay,

O’ercharg’d with burthen of mine own love’s might.

O! let my looks be then the eloquence

And dumb presagers of my speaking breast,

Who plead for love, and look for recompense,

More than that tongue that more hath more express’d.

O! learn to read what silent love hath writ:

To hear with eyes belongs to love’s fine wit.

29

When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself, and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featur’d like him, like him with friends possess’d,

Desiring this man’s art, and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts my self almost despising,

Haply I think on thee,– and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

For thy sweet love remember’d such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

30

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste:

Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow,

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since cancell’d woe,

And moan the expense of many a vanish’d sight:

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er

The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restor’d and sorrows end.

33

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy;

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine,

With all triumphant splendour on my brow;

But out! alack! he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath mask’d him from me now.

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth;

Suns of the world may stain when heaven’s sun staineth.

35

No more be griev’d at that which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns, and silver fountains mud:

Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun,

And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud.

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare,

Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss,

Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are;

For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense,–

Thy adverse party is thy advocate,–

And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence:

Such civil war is in my love and hate,

That I an accessary needs must be,

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

55

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmear’d with sluttish time.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword, nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

‘Gainst death, and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

So, till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes.

60

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown’d,

Crooked eclipses ‘gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow:

And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand.

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

62

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account;

And for myself mine own worth do define,

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me myself indeed

Beated and chopp’d with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read;

Self so self-loving were iniquity.

‘Tis thee,–myself,–that for myself I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O! how shall summer’s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O! none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

71

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O! if,–I say you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse;

But let your love even with my life decay;

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

73

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed, whereon it must expire,

Consum’d with that which it was nourish’d by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well, which thou must leave ere long.

74

But be contented: when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee:

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me:

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead;

The coward conquest of a wretch’s knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

80

O! how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might,

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame!

But since your worth–wide as the ocean is,–

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride;

Or, being wrack’d, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building, and of goodly pride:

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this,–my love was my decay.

85

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still,

While comments of your praise richly compil’d,

Reserve their character with golden quill,

And precious phrase by all the Muses fil’d.

I think good thoughts, whilst others write good words,

And like unlettered clerk still cry ‘Amen’

To every hymn that able spirit affords,

In polish’d form of well-refined pen.

Hearing you praised, I say ”tis so, ’tis true,’

And to the most of praise add something more;

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

Then others, for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect.

87

Farewell! thou art too dear for my possessing,

And like enough thou know’st thy estimate,

The charter of thy worth gives thee releasing;

My bonds in thee are all determinate.

For how do I hold thee but by thy granting?

And for that riches where is my deserving?

The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting,

And so my patent back again is swerving.

Thy self thou gav’st, thy own worth then not knowing,

Or me to whom thou gav’st it, else mistaking;

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing,

Comes home again, on better judgement making.

Thus have I had thee, as a dream doth flatter,

In sleep a king, but waking no such matter.

93

So shall I live, supposing thou art true,

Like a deceived husband; so love’s face

May still seem love to me, though alter’d new;

Thy looks with me, thy heart in other place:

For there can live no hatred in thine eye,

Therefore in that I cannot know thy change.

In many’s looks, the false heart’s history

Is writ in moods, and frowns, and wrinkles strange.

But heaven in thy creation did decree

That in thy face sweet love should ever dwell;

Whate’er thy thoughts, or thy heart’s workings be,

Thy looks should nothing thence, but sweetness tell.

How like Eve’s apple doth thy beauty grow,

If thy sweet virtue answer not thy show!

94

They that have power to hurt, and will do none,

That do not do the thing they most do show,

Who, moving others, are themselves as stone,

Unmoved, cold, and to temptation slow;

They rightly do inherit heaven’s graces,

And husband nature’s riches from expense;

They are the lords and owners of their faces,

Others, but stewards of their excellence.

The summer’s flower is to the summer sweet,

Though to itself, it only live and die,

But if that flower with base infection meet,

The basest weed outbraves his dignity:

For sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds;

Lilies that fester, smell far worse than weeds.

97

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

What freezings have I felt, what dark days seen!

What old December’s bareness everywhere!

And yet this time removed was summer’s time;

The teeming autumn, big with rich increase,

Bearing the wanton burden of the prime,

Like widow’d wombs after their lords’ decease:

Yet this abundant issue seem’d to me

But hope of orphans, and unfather’d fruit;

For summer and his pleasures wait on thee,

And, thou away, the very birds are mute:

Or, if they sing, ’tis with so dull a cheer,

That leaves look pale, dreading the winter’s near.

98

From you have I been absent in the spring,

When proud-pied April, dress’d in all his trim,

Hath put a spirit of youth in every thing,

That heavy Saturn laugh’d and leap’d with him.

Yet nor the lays of birds, nor the sweet smell

Of different flowers in odour and in hue,

Could make me any summer’s story tell,

Or from their proud lap pluck them where they grew:

Nor did I wonder at the lily’s white,

Nor praise the deep vermilion in the rose;

They were but sweet, but figures of delight,

Drawn after you, you pattern of all those.

Yet seem’d it winter still, and you away,

As with your shadow I with these did play.

105

Let not my love be call’d idolatry,

Nor my beloved as an idol show,

Since all alike my songs and praises be

To one, of one, still such, and ever so.

Kind is my love to-day, to-morrow kind,

Still constant in a wondrous excellence;

Therefore my verse to constancy confin’d,

One thing expressing, leaves out difference.

‘Fair, kind, and true,’ is all my argument,

‘Fair, kind, and true,’ varying to other words;

And in this change is my invention spent,

Three themes in one, which wondrous scope affords.

Fair, kind, and true, have often liv’d alone,

Which three till now, never kept seat in one.

106

When in the chronicle of wasted time

I see descriptions of the fairest wights,

And beauty making beautiful old rime,

In praise of ladies dead and lovely knights,

Then, in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best,

Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,

I see their antique pen would have express’d

Even such a beauty as you master now.

So all their praises are but prophecies

Of this our time, all you prefiguring;

And for they looked but with divining eyes,

They had not skill enough your worth to sing:

For we, which now behold these present days,

Have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise.

107

Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul

Of the wide world dreaming on things to come,

Can yet the lease of my true love control,

Supposed as forfeit to a confin’d doom.

The mortal moon hath her eclipse endur’d,

And the sad augurs mock their own presage;

Incertainties now crown themselves assur’d,

And peace proclaims olives of endless age.

Now with the drops of this most balmy time,

My love looks fresh, and Death to me subscribes,

Since, spite of him, I’ll live in this poor rime,

While he insults o’er dull and speechless tribes:

And thou in this shalt find thy monument,

When tyrants’ crests and tombs of brass are spent.

110

Alas! ’tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view,

Gor’d mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new;

Most true it is, that I have look’d on truth

Askance and strangely; but, by all above,

These blenches gave my heart another youth,

And worse essays prov’d thee my best of love.

Now all is done, save what shall have no end:

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A god in love, to whom I am confin’d.

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O, no! it is an ever-fixed mark,

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me prov’d,

I never writ, nor no man ever lov’d.

126

O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power

Dost hold Time’s fickle glass, his fickle hour;

Who hast by waning grown, and therein show’st

Thy lovers withering, as thy sweet self grow’st.

If Nature, sovereign mistress over wrack,

As thou goest onwards, still will pluck thee back,

She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill

May time disgrace and wretched minutes kill.

Yet fear her, O thou minion of her pleasure!

She may detain, but not still keep, her treasure:

Her audit (though delayed) answered must be,

And her quietus is to render thee.

127

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were, it bore not beauty’s name;

But now is black beauty’s successive heir,

And beauty slander’d with a bastard shame:

For since each hand hath put on Nature’s power,

Fairing the foul with Art’s false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name, no holy bower,

But is profan’d, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress’ eyes are raven black,

Her eyes so suited, and they mourners seem

At such who, not born fair, no beauty lack,

Sland’ring creation with a false esteem:

Yet so they mourn becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so.

128

How oft when thou, my music, music play’st,

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers when thou gently sway’st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those jacks that nimble leap,

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand,

Whilst my poor lips which should that harvest reap,

At the wood’s boldness by thee blushing stand!

To be so tickled, they would change their state

And situation with those dancing chips,

O’er whom thy fingers walk with gentle gait,

Making dead wood more bless’d than living lips.

Since saucy jacks so happy are in this,

Give them thy fingers, me thy lips to kiss.

129

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action: and till action, lust

Is perjur’d, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;

Enjoy’d no sooner but despised straight;

Past reason hunted; and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallow’d bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad:

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest, to have extreme;

A bliss in proof,– and prov’d, a very woe;

Before, a joy propos’d; behind a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,–

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

135

Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy ‘Will,’

And ‘Will’ to boot, and ‘Will’ in over-plus;

More than enough am I that vex’d thee still,

To thy sweet will making addition thus.

Wilt thou, whose will is large and spacious,

Not once vouchsafe to hide my will in thine?

Shall will in others seem right gracious,

And in my will no fair acceptance shine?

The sea, all water, yet receives rain still,

And in abundance addeth to his store;

So thou, being rich in ‘Will,’ add to thy ‘Will’

One will of mine, to make thy large will more.

Let no unkind ‘No’ fair beseechers kill;

Think all but one, and me in that one ‘Will.’

138

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutor’d youth,

Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed:

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O! love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love, loves not to have years told:

Therefore I lie with her, and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flatter’d be.

144

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still:

The better angel is a man right fair,

The worser spirit a woman colour’d ill.

To win me soon to hell, my female evil,

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil,

Wooing his purity with her foul pride.

And whether that my angel be turn’d fiend,

Suspect I may, yet not directly tell;

But being both from me, both to each friend,

I guess one angel in another’s hell:

Yet this shall I ne’er know, but live in doubt,

Till my bad angel fire my good one out.

146

Poor soul, the centre of my sinful earth,

My sinful earth these rebel powers array,

Why dost thou pine within and suffer dearth,

Painting thy outward walls so costly gay?

Why so large cost, having so short a lease,

Dost thou upon thy fading mansion spend?

Shall worms, inheritors of this excess,

Eat up thy charge? Is this thy body’s end?

Then soul, live thou upon thy servant’s loss,

And let that pine to aggravate thy store;

Buy terms divine in selling hours of dross;

Within be fed, without be rich no more:

So shall thou feed on Death, that feeds on men,

And Death once dead, there’s no more dying then.

147

My love is as a fever longing still,

For that which longer nurseth the disease;

Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill,

The uncertain sickly appetite to please.

My reason, the physician to my love,

Angry that his prescriptions are not kept,

Hath left me, and I desperate now approve

Desire is death, which physic did except.

Past cure I am, now Reason is past care,

And frantic-mad with evermore unrest;

My thoughts and my discourse as madmen’s are,

At random from the truth vainly express’d;

For I have sworn thee fair, and thought thee bright,

Who art as black as hell, as dark as night.

152

In loving thee thou know’st I am forsworn,

But thou art twice forsworn, to me love swearing;

In act thy bed-vow broke, and new faith torn,

In vowing new hate after new love bearing:

But why of two oaths’ breach do I accuse thee,

When I break twenty? I am perjur’d most;

For all my vows are oaths but to misuse thee,

And all my honest faith in thee is lost:

For I have sworn deep oaths of thy deep kindness,

Oaths of thy love, thy truth, thy constancy;

And, to enlighten thee, gave eyes to blindness,

Or made them swear against the thing they see;

For I have sworn thee fair; more perjur’d I,

To swear against the truth so foul a lie!

Source Text

Shakespeare, William. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Project Gutenberg, 2014, is licensed under no known copyright.