16 Cúchulainn’s Boyish Deeds

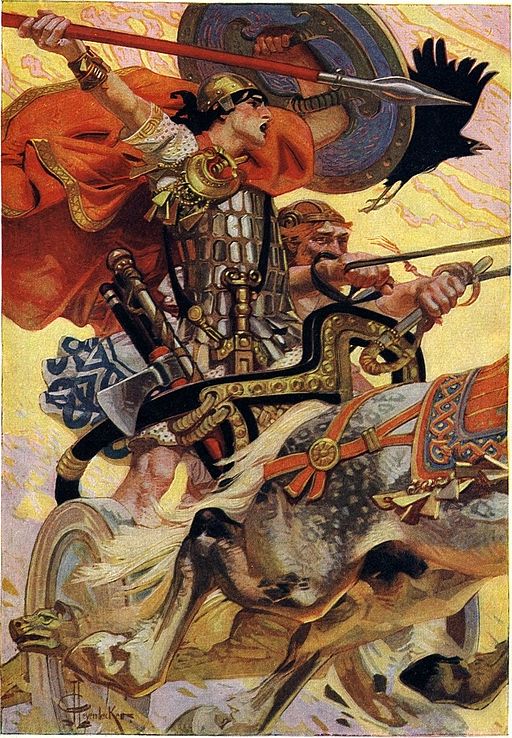

“Cuchlain in Battle” by J.C. Leyendecker, 1910. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Annie Khan

Cuchulainn is a significant mythological character in the Ulster cycle (formerly called the “Red Branch Cycle”), which is a group of stories that constitute the foundational texts of Irish mythology said to have taken place around the first century A.D (“Ulster Cycle”). Ulster, formerly known as Ulaid, is one of Ireland’s four provinces consisting of nine counties most of which are in modern-day Northern Ireland.

The story of Cuchulainn was written eight hundred years ago and before that, it was spread by word of mouth as part of the oral tradition. It was written as an epic in Tain Bo Cuailnge (commonly translated as “The Cattle Raid of Cooley”) which sometimes compared to the Illiad in importance and themes. The first English translation of this story was published in 1904 by Winifred Farady (“Tain Bo Cuailgne”).

Cuchulainn’s character resembles the Greek hero Heracles to whom he is often compared. He has immense strength which is not a quality any human can possess. He is the son of God Lugh which is why he has god-like powers, especially in a battle, where he is sometimes called “half-man” and “half-beast” due to his rage. His mother is Deichtine who, in the later version of this story, is the sister of the king of Ulster, named Conchobar Mac Nessa. Cuchulainn’s birth name was Setanta. He earned the name “Cuchulainn” at the age of twelve which means “Hound of Ulster” because he killed Culann’s guard dog and promised to take its place until the replacement was found. Cuchulainn grew up in a county in mid-east Ireland called Louth and he was a warrior in King Conchobar’s army. He showed extreme physical strength from a young age. He is most famous for the battle called “Cattle Raid of Cooley” in which he fought Queen Medb of Connacht”s army, from western Ireland, single-handedly because the rest of his army was put under a curse. According to a prophecy given by a priest, named Cathbad, Cuchulainn will have everlasting fame but his life will be short-lived. The prophecy came true since he died at the young age of twenty-seven.

Summary

The story of Cuchulainn’s childhood adventures is being told to Queen Medb, whose army was defeated by Cuchulainn alone at the Cattle Raid of Cooley, by Fiacha Mac Fir-Febe. The story starts with the day when Cathbud gives the prophecy that one of his students who bears arms will have everlasting fame, but his life will be short-lived. Cuchulainn, who is seven years old at the time, doesn’t listen to the full prophecy and bears arms in the desire for fame. Since none of the weapons can withstand his strength, King Conchobar gives Cuchulainn his own weapons and chariot. This takes place in Emain Macha which is the capital and political center of Ulster. Cuchulainn is confident in his abilities which makes him impulsive and not scared of anything. He forces the charioteer to take him around Emain Macha at first then to wherever the road will lead them thereafter. On this adventure, he kills three sons of Nechta Scene because they bragged about killing more Ulstermen than are alive. He takes their heads as trophies. On the way back, he captures a wild deer and a flock of swans, too. As he gives a dramatic and enraged entrance in Emain Macha, he challenges people to fight him. The wife of the king along with other women stop him by showing their bare breasts which leads to his capture. He is then dipped in cold water three times so he can be calmed. Since that day he always sat on King Conchobar’s knee.

Historical Context

It is believed that the ancient people who occupied Ireland possessed magical qualities which is why Irish literature includes mythological characters and legendary heroes who were thought to be god-like. Stories about Ulster are a big part of Irish literature and sheds a light on how the people lived and what was considered more important. Ancient Irish literature seems to be more about honor and possessions than human compassion. The mythological stories were recorded mostly in 12th century A.D by Christian monks who relayed the stories of fairies, warriors, kings, and queens as “god-like” figures rather than the pagan deities they would have represented to the ancient Irish.

Themes

There are several themes presented in this story. Cuchulainn’s fierce fighting skills from a young age show the strength he possesses. He accepts what he did wrong and makes up for his mistake like taking the place of a guard dog. At the same time, he is very impulsive and acts before he can rationalize like he didn’t fully hear the prophecy. He is quick to take revenge and he is very confident which shows his immaturity. He likes fame and would do anything to achieve it. He likes to show off his skills as well. Being all this, he is still a seven-year-old boy who felt embarrassed at the sight of naked women which shows respect.

Works Cited

“Tain Bo Cuailgne.” Wikipedia. 10 Mar. 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1in_B%C3%B3_C%C3%BAailnge. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

“Ulster.” Encyclopedia Britannica. N.d. www.britannica.com/place/Ulster-historic-province-Ireland. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

“Ulster Cycle.” Wikipedia. 23 Apr. 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulster_Cycle. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think that mythological characters like Cuchulainn were created and what do they represent?

- Why do you think that Cuchulainn is shown as the child of God? What does his superhuman ability represent?

- What did Cuchulainn brought back with him to Emain Macha? What does it represent about his character? Did the author use imagery to describe this event?

- Can you relate the themes presented in this story to modern time? Can you compare Cuchulainn’s mental status to any real character from 20th or 21st century?

- Do you think that this story changed overtime? If you could change one thing in this story what would it be?

Further Resources

- YouTube clip of Overly Sarcastic Production‘s overview of Cu Cuchlainn.

- Academic article comparing Cuchuclainn with other mythological heroes.

- A Podcast, Mythology, dramatizing the story of Cuchulainn.

Reading: From Cuchulainn’s Boyish Deeds

‘He did another exploit,’ said Fiacha Mac Fir-Febe. ‘Cathbad the Druid was with his son, Conchobar Mac Nessa. A hundred active men were with him, learning magic from him. That is the number that Cathbad used to teach. A certain one of his pupils asked of him for what this day would be good. Cathbad said a warrior should take arms therein whose name should be over Ireland forever, for deed of valour, and his fame should continue forever. Cuchulainn heard this. He comes to Conchobar to ask for arms. Conchobar said, “Who has instructed you?”

‘”My friend Cathbad,” said Cuchulainn.

‘”We know indeed,” said Conchobar.

‘He gave him spear and shield. He brandished them in the middle of the house, so that nothing remained of the fifteen sets of armour that were in store in Conchobar’s household against the breaking of weapons or taking of arms by any one. Conchobar’s own armour was given to him. That withstood him, and he brandished it, and blessed the king whose armour it was, and said, “Blessing to the people and race to whom is king the man whose armour that is.”

‘Then Cathbad came to them, and said: “Has the boy taken arms?” said Cathbad.

‘”Yes,” said Conchobar.

‘”This is not lucky for the son of his mother,” said he.

‘”What, is it not you advised it?” said Conchobar.

‘”Not I, surely,” said Cathbad.

‘”What advantage to you to deceive me, wild boy?” said Conchobar to

Cuchulainn.

‘”O king of heroes, it is no trick,” said Cuchulainn; “it is he who taught it to his pupils this morning; and I heard him, south of Emain, and I came to you then.”

‘”The day is good thus,” said Cathbad; “it is certain he will be famous and renowned, who shall take arms therein; but he will be short-lived only.”

‘”A wonder of might,” said Cuchulainn; “provided I be famous, I am content though I were but one day in the world.”

‘Another day a certain man asked the druids what it is for which that day was good.

‘”Whoever shall go into a chariot therein,” said Cathbad, “his name shall be over Ireland for ever.”

‘Then Cuchulainn heard this; he comes to Conchobar and said to him: “O friend Conchobar,” said he, “give me a chariot.” He gave him a chariot. He put his hand between the two poles [Note: The fertais were poles sticking out behind the chariot, as the account of the wild deer, later, shows.] of the chariot, so that the chariot broke. He broke twelve chariots in this way. Then Conchobar’s chariot was given to him. This withstood him. He goes then in the chariot, and Conchobar’s charioteer with him. The charioteer (Ibor was his name) turned the chariot under him. “Come out of the chariot now,” said the charioteer.

‘”The horses are fine, and I am fine, their little lad,” said Cuchulainn. “Go forward round Emain only, and you shall have a reward for it.”

‘So the charioteer goes, and Cuchulainn forced him then that he should go on the road to greet the boys “and that the boys might bless me.”

‘He begged him to go on the way again. When they come, Cuchulainn said to the charioteer: “Ply the goad on the horses,” said he.

‘”In what direction?” said the charioteer.

‘”As long as the road shall lead us,” said Cuchulainn.

‘They come thence to Sliab Fuait, and find Conall Cernach there. It fell to Conall that day to guard the province; for every hero of Ulster was in Sliab Fuait in turn, to protect any one who should come with poetry, or to fight against a man; so that it should be there that there should be some one to encounter him, that no one should go to Emain unperceived.

‘”May that be for prosperity,” said Conall; “may it be for victory and triumph.”

‘”Go to the fort, O Conall, and leave me to watch here now,” said

Cuchulainn.

‘”It will be enough,” said Conall, “if it is to protect any one with poetry; if it is to fight against a man, it is early for you yet.”

‘”Perhaps it may not be necessary at all,” said Cuchulainn. “Let us go meanwhile,” said Cuchulainn, “to look upon the edge of Loch Echtra. Heroes are wont to abide there.”

‘”I am content,” said Conall.

‘Then they go thence. He throws a stone from his sling, so that a pole of Conall Cernach’s chariot breaks.

‘”Why have you thrown the stone, O boy?” said Conall.

“To try my hand and the straightness of my throw,” said Cuchulainn; “and it is the custom with you Ulstermen, that you do not travel beyond your peril. Go back to Emain, O friend Conall, and leave me here to watch.”

‘”Content, then,” said Conall.

‘Conall Cernach did not go past the place after that. Then Cuchulainn goes forth to Loch Echtra, and they found no one there before them. The charioteer said to Cuchulainn that they should go to Emain, that they might be in time for the drinking there.

‘”No,” said Cuchulainn. “What mountain is it yonder?” said

Cuchulainn.

‘”Sliab Monduirn,” said the charioteer.

‘”Let us go and get there,” said Cuchulainn. They go then till they reach it. When they had reached the mountain, Cuchulainn asked: “What is the white cairn yonder on the top of the mountain?”

‘”Find Carn,” said the charioteer.

‘”What plain is that over there?” said Cuchulainn.

‘”Mag Breg,” said the charioteer. He tells him then the name of every chief fort between Temair and Cenandas. He tells him first their meadows and their fords, their famous places and their dwellings, their fortresses and their high hills. He shows [Note: Reading with YBL.] him then the fort of the three sons of Nechta Scene; Foill, Fandall, and Tuachell were their names.

‘”Is it they who say,” said Cuchulainn, “that there are not more of the Ulstermen alive than they have slain of them?”

‘”It is they indeed,” said the charioteer.

‘”Let us go till we reach them,” said Cuchulainn.

‘”Indeed it is peril to us,” said the charioteer.

‘”Truly it is not to avoid it that we go,” said Cuchulainn.

‘Then they go forth and unharness their horses at the meeting of the bog and the river, to the south above the fort of the others; and he threw the withe that was on the pillar as far as he could throw into the river and let it go with the stream, for this was a breach of geis to the sons of Nechta Scene. They perceive it then, and come to them. Cuchulainn goes to sleep by the pillar after throwing the withe at the stream; and he said to the charioteer: “Do not waken me for few; but waken me for many.”

‘Now the charioteer was very frightened, and he made ready their chariot and pulled its coverings and skins which were over Cuchulainn; for he dared not waken him, because Cuchulainn told him at first that he should not waken him for a few.

‘Then come the sons of Nechta Scene.

‘”Who is it who is there?” said one of them.

‘”A little boy who has come to-day into the chariot for an expedition,” said the charioteer.

‘”May it not be for his happiness,” said the champion; “and may it not be for his prosperity, his first taking of arms. Let him not be in our land, and let the horses not graze there any more,” said the champion.

‘”Their reins are in my hands,” said the charioteer.

‘”It should not be yours to earn hatred,” said Ibar to the champion; “and the boy is asleep.”

‘”I am not a boy at all,” said Cuchulainn; “but it is to seek battle with a man that the boy who is here has come.”

‘”That pleases me well,” said the champion.

‘”It will please you now in the ford yonder,” said Cuchulainn.

‘”It befits you,” said the charioteer, “take heed of the man who comes against you. Foill is his name,” said he; “for unless you reach him in the first thrust, you will not reach him till evening.”

‘”I swear by the god by whom my people swear, he will not ply his skill on the Ulstermen again, if the broad spear of my friend Conchobar should reach him from my hand. It will be an outlaw’s hand to him.”

‘Then he cast the spear at him, so that his back broke. He took with him his accoutrements and his head.

‘”Take heed of another man,” said the charioteer, “Fandall [Note: i.e. ‘Swallow.’] is his name. Not more heavily does he traverse(?) the water than swan or swallow.”

‘”I swear that he will not ply that feat again on the Ulstermen,” said Cuchulainn. “You have seen,” said he, “the way I travel the pool at Emain.”

‘They meet then in the ford. Cuchulainn kills that man, and took his head and his arms.

‘”Take heed of another man who comes towards you,” said the charioteer. “Tuachell [Note: i.e. ‘Cunning.’] is his name. It is no misname for him, for he does not fall by arms at all.”

‘”Here is the javelin for him to confuse him, so that it may make a red-sieve of him,” said Cuchulainn.

‘He cast the spear at him, so that it reached him in his ——. Then He went to him and cut off his head. Cuchulainn gave his head and his accoutrements to his own charioteer. He heard then the cry of their mother, Nechta Scene, behind them.

‘He puts their spoils and the three heads in his chariot with him, and said: “I will not leave my triumph,” said he, “till I reach Emain Macha.” ‘then they set out with his triumph.

‘Then Cuchulainn said to the charioteer: “You promised us a good run,” said he, “and we need it now because of the strife and the pursuit that is behind us.” They go on to Sliab Fuait; and such was the speed of the run that they made over Breg after the spurring of the charioteer, that the horses of the chariot overtook the wind and the birds in flight, and that Cuchulainn caught the throw that he sent from his sling before it reached the ground.

‘When they reached Sliab Fuait, they found a herd of wild deer there before them.

‘”What are those cattle yonder so active?” said Cuchulainn.

‘”Wild deer,” said the charioteer.

‘”Which would the Ulstermen think best,” said Cuchulainn, “to bring them dead or alive?”

‘”It is more wonderful alive,” said the charioteer; “it is not every one who can do it so. Dead, there is not one of them who cannot do it. You cannot do this, to carry off any of them alive,” said the charioteer.

‘”I can indeed,” said Cuchulainn. “Ply the goad on the horses into the bog.”

‘The charioteer does this. The horses stick in the bog. Cuchulainn sprang down and seized the deer that was nearest, and that was the finest of them. He lashed the horses through the bog, and overcame the deer at once, and bound it between the two poles of the chariot.

‘They saw something again before them, a flock of swans.

‘”Which would the Ulstermen think best,” said Cuchulainn, “to have them dead or alive?”

‘”All the most vigorous and finest(?) bring them alive,” said the charioteer.

‘Then Cuchulainn aims a small stone at the birds, so that he struck eight of the birds. He threw again a large stone, so that he struck twelve of them. All that was done by his return stroke.

“Collect the birds for us,” said Cuchulainn to his charioteer. “If it is I who go to take them,” said he, “the wild deer will spring upon you.”

‘”It is not easy for me to go to them,” said the charioteer. “The horses have become wild so that I cannot go past them. I cannot go past the two iron tyres [Interlinear gloss, fonnod. The fonnod was some part of the rim of the wheel apparently.] of the chariot, because of their sharpness; and I cannot go past the deer, for his horn has filled all the space between the two poles of the chariot.”

‘”Step from its horn,” said Cuchulainn. “I swear by the god by whom the Ulstermen swear, the bending with which I will bend my head on him, and the eye that I will make at him, he will not turn his head on you, and he will not dare to move.”

‘That was done then. Cuchulainn made fast the reins, and the charioteer collects the birds. Then Cuchulainn bound the birds from the strings and thongs of the chariot; so that it was thus he went to Emain Macha: the wild deer behind his chariot, and the flock of swans flying over it, and the three heads in his chariot. Then they come to Emain.

“A man in a chariot is coming to you,” said the watchman in Emain Macha; “he will shed the blood of every man who is in the court, unless heed is taken, and unless naked women go to him.”

‘Then he turned the left side of his chariot towards Emain, and that was a geis [Note: i.e. it was an insult.] to it; and Cuchulainn said: “I swear by the god by whom the Ulstermen swear, unless a man is found to fight with me, I will shed the blood of every one who is in the fort.”

‘”Naked women to meet him!” said Conchobar.

‘Then the women of Emain go to meet him with Mugain, the wife of Conchobar Mac Nessa, and bare their breasts before him. “These are the warriors who will meet you to-day,” said Mugain.

‘He covers his face; then the heroes of Emain seize him and throw him into a vessel of cold water. That vessel bursts round him. The second vessel into which he was thrown boiled with bubbles as big as the fist therefrom. The third vessel into which he went, he warmed it so that its heat and its cold were rightly tempered. Then he comes out; and the queen, Mugain, puts a blue mantle on him, and a silver brooch therein, and a hooded tunic; and he sits at Conchobar’s knee, and that was his couch always after that. The man who did this in his seventh year,’ said Fiacha Mac Fir-Febe, ‘it were not wonderful though he should rout an overwhelming force, and though he should exhaust (?) an equal force, when his seventeen years are complete to-day.’

Source Text:

The Cattle-Raid of Cualnge (Tain Bo Cualnge). Sign of the Phoenix, 1904, is licensed under no known copyright.