2 Bede: From Ecclesiastical History of the English People

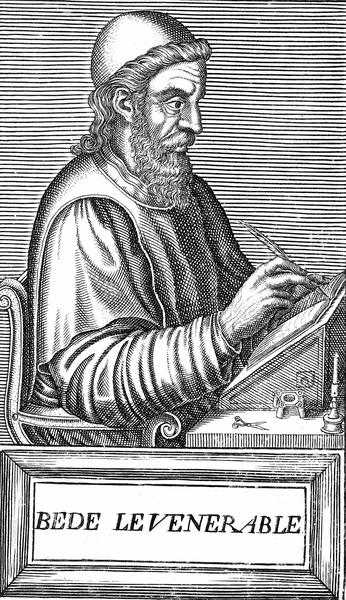

“Szent Béda avagy Beda Venerabilis” by unknown artist. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Stephanie Brower

Bede’s famous account begins with the invasion of the British Isles by Roman forces; as such, it is considered one of the most important historical records documenting Roman rule, Anglo-Saxon settlement and the evolution of the Church on the island. Due to its focus on Anglo-Saxon history, it has been cited as a key foundational text in the forming of a national English identity (“Bede”).

Biography

The “Venerable Bede” was a monk, scholar and prolific author, most famously An Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum), which is how he came to be regarded as the “Father of English History.”

Considering the little amount known about Bede, it is believed that he was born on the very monastery grounds where he would later live in Jarrow, England, in 672 or 673 AD (Fiorentino). He lived in the Kingdom of Northumbria, where he spent his youth being exposed to religious surroundings and was educated to write in both Latin and English. He became a deacon early on in life and by the age of 30, he was ordained a priest. He took interest in writing and wrote about 40 books, his main interests being theology and history. Records show that he had contact with other scholars and prominent people both in Britain and the continent; his greatest work was dedicated to King Ceolwulf of Northumbria (Fiorentino). One of his major legacies was the establishment of our modern dating system (from the birth of Christ forward).

He wrote his most famous work in 731, just years before his death in 735 AD. He became known as the “Venerable Bede,” and was generally regarded as a saint shortly after his death but was only officially canonized by the Catholic church in the 19th century.

Historic Context

Bede’s intent was to demonstrate how the English church had established itself and grown throughout England; he is clearly angered at the native Britons for their lackluster attempts at converting the invading Anglo-Saxons. Furthermore, he takes great pains to argue for an alternative Easter date which seems to be a sore point for him in the text below. Scholars speculate that he penned this work to argue a reform agenda to Ceowulf which is why the Ecclesiastical History contains a more optimistic tone about the state of the English church than Bede’s private writings from the same time period (“Bede”).

Bede’s History is considered to be one of the first important works of Christian history since the Acts of the Apostles and the one of the only sources to describe England’s early history (along with Gildas’ account in the previous chapter). His work, while primarily composed in Latin, also contains examples of Old English including what is considered the earliest work of English literature: Caedmon’s Hymn.

There isn’t much known about the history behind his literary works. However, it was known that the sources for the earliest accounts in An Ecclesiastical History came from what he liked to consider primum scripta, or “early writings”, dating back from before his time, in 55 CE. Primary sources that were used came from information gathered of a few of the early English (Roman) historians, such as Pliny, Eutropius, and Gildas.

Summary

The Ecclesiastical History is a five-book series, each containing stories that serve as the only source documenting the conversion to Christianity of the Anglo-Saxon tribes. It tells the story of Britons from Julius Caesar’s invasion, to Bede’s present in the 8th century.

He tells the story of battles, conversions and miracles performed by monks and bishops. In book I, Bede goes into detail about Britain’s early history from the Roman invasion and how they were left to handle the remnants. Book II describes Bede’s argument to convince the Northumbrian peoples to convert to Christianity. However, Bede depicts, in Book III, the return of Northumbrians to paganism. Book VI goes on to describe the organization and establishment of Christianity in the English church. The long book ends at book V, which covers the personal history of Holy Ethelwald, miracles of growth within the English church, such as the development of the bishopric.

Works Cited

“Bede.” Wikipedia, 28 Apr. 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bede. Accessed 02 May 2020.

Fiorentino, Wesley. “Bede.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, 10 May 2017, www.ancient.eu/Bede/. Accessed 02 May 2020.

Discussion Questions

- Which is the dominant theme in the excerpts below: history or religion?

- How accurate do you believe the information Bede gathered from the early historians was? Is this a historical work or a work of political propaganda?

- The last book in the series focuses on Holy Ethelwald and his miracles in the church. What was the purpose of bringing this man into his story?

- There was very little information known about Bede, besides what he explicitly wrote in his writings about himself. Why do you think that is?

- How does Bede regard the English people? How might this have affected later accounts and perceptions?

Further Resources

- The first part of a three-part documentary series on “How God Made the English” focusing on Bede’s contributions to language, theology and English identity

- A podcast from BBC’s “In Our Time” on the Venerable Bede

- The British Library’s webpage on Bede

- “Caedmon’s Hymn” (sung in Old English) as part of the Medieval Tales in Performance series

Reading: From An Ecclesiastical History of the English People

A Description of the Island of Britain and its Inhabitants

Britain, an island in the Atlantic, formerly called Albion, lies to the north-west, facing, though at a considerable distance, the coasts of Germany, France, and Spain, which form the greatest part of Europe. It extends 800 miles in length towards the north, and is 200 miles in breadth, except where several promontories extend further in breadth, by which its compass is made to be 4,875 miles. To the south lies Belgic Gaul. To its nearest shore there is an easy passage from the city of Rutubi Portus, by the English now corrupted into Reptacaestir. The distance from here across the sea to Gessoriacum, the nearest shore in the territory of the Morini, is fifty miles, or as some writers say, 450 furlongs. On the other side of the island, where it opens upon the boundless ocean, it has the islands called Orcades. Britain is rich in grain and trees, and is well adapted for feeding cattle and beasts of burden. It also produces vines in some places, and has plenty of land and water fowl of divers sorts; it is remarkable also for rivers abounding in fish, and plentiful springs. It has the greatest plenty of salmon and eels; seals are also frequently taken, and dolphins, as also whales; besides many sorts of shell-fish, such as mussels, in which are often found excellent pearls of all colours, red, purple, violet and green, but chiefly white. There is also a great abundance of snails, of which the scarlet dye is made, a most beautiful red, which never fades with the heat of the sun or exposure to rain, but the older it is, the more beautiful it becomes. It has both salt and hot springs, and from them flow rivers which furnish hot baths, proper for all ages and both sexes, in separate places, according to their requirements. For water, as St. Basil says, receives the quality of heat, when it runs along certain metals, and becomes not only hot but scalding. Britain is rich also in veins of metals, as copper, iron, lead, and silver; it produces a great deal of excellent jet, which is black and sparkling, and burns when put to the fire, and when set on fire, drives away serpents; being warmed with rubbing, it attracts whatever is applied to it, like amber. The island was formerly distinguished by twenty-eight famous cities, besides innumerable forts, which were all strongly secured with walls, towers, gates, and bars. And, because it lies almost under the North Pole, the nights are light in summer, so that at midnight the beholders are often in doubt whether the evening twilight still continues, or that of the morning has come; since the sun at night returns to the east in the northern regions without passing far beneath the earth. For this reason the days are of a great length in summer, and on the other hand, the nights in winter are eighteen hours long, for the sun then withdraws into southern parts. In like manner the nights are very short in summer, and the days in winter, that is, only six equinoctial hours. Whereas, in Armenia, Macedonia, Italy, and other countries of the same latitude, the longest day or night extends but to fifteen hours, and the shortest to nine.

There are in the island at present, following the number of the books in which the Divine Law was written, five languages of different nations employed in the study and confession of the one self-same knowledge, which is of highest truth and true sublimity, to wit, English, British, Scottish, Pictish, and Latin, the last having become common to all by the study of the Scriptures. But at first this island had no other inhabitants but the Britons, from whom it derived its name, and who, coming over into Britain, as is reported, from Armorica, possessed themselves of the southern parts thereof. Starting from the south, they had occupied the greater part of the island, when it happened, that the nation of the Picts, putting to sea from Scythia, as is reported, in a few ships of war, and being driven by the winds beyond the bounds of Britain, came to Ireland and landed on its northern shores. There, finding the nation of the Scots, they begged to be allowed to settle among them, but could not succeed in obtaining their request. Ireland is the largest island next to Britain, and lies to the west of it; but as it is shorter than Britain to the north, so, on the other hand, it runs out far beyond it to the south, over against the northern part of Spain, though a wide sea lies between them. The Picts then, as has been said, arriving in this island by sea, desired to have a place granted them in which they might settle. The Scots answered that the island could not contain them both; but “We can give you good counsel,” said they, “whereby you may know what to do; we know there is another island, not far from ours, to the eastward, which we often see at a distance, when the days are clear. If you will go thither, you can obtain settlements; or, if any should oppose you, we will help you.” The Picts, accordingly, sailing over into Britain, began to inhabit the northern parts thereof, for the Britons had possessed themselves of the southern. Now the Picts had no wives, and asked them of the Scots; who would not consent to grant them upon any other terms, than that when any question should arise, they should choose a king from the female royal race rather than from the male: which custom, as is well known, has been observed among the Picts to this day. In process of time, Britain, besides the Britons and the Picts, received a third nation, the Scots, who, migrating from Ireland under their leader, Reuda, either by fair means, or by force of arms, secured to themselves those settlements among the Picts which they still possess. From the name of their commander, they are to this day called Dalreudini; for, in their language, Dal signifies a part.

Ireland is broader than Britain and has a much healthier and milder climate; for the snow scarcely ever lies there above three days: no man makes hay in the summer for winter’s provision, or builds stables for his beasts of burden. No reptiles are found there, and no snake can live there; for, though snakes are often carried thither out of Britain, as soon as the ship comes near the shore, and the scent of the air reaches them, they die. On the contrary, almost all things in the island are efficacious against poison. In truth, we have known that when men have been bitten by serpents, the scrapings of leaves of books that were brought out of Ireland, being put into water, and given them to drink, have immediately absorbed the spreading poison, and assuaged the swelling.

The island abounds in milk and honey, nor is there any lack of vines, fish, or fowl; and it is noted for the hunting of stags and roe-deer. It is properly the country of the Scots, who, migrating from thence, as has been said, formed the third nation in Britain in addition to the Britons and the Picts.

There is a very large gulf of the sea, which formerly divided the nation of the Britons from the Picts; it runs from the west far into the land, where, to this day, stands a strong city of the Britons, called Alcluith. The Scots, arriving on the north side of this bay, settled themselves there.

The Coming of the English to Britain

In the year of our Lord 423, Theodosius, the younger, the forty-fifth from Augustus, succeeded Honorius and governed the Roman empire twenty-six years. In the eighth year of his reign, Palladius was sent by Celestinus, the Roman pontiff, to the Scots that believed in Christ, to be their first bishop. In the twenty-third year of his reign, Aetius, a man of note and a patrician, discharged his third consulship with Symmachus for his colleague. To him the wretched remnant of the Britons sent a letter, which began thus:—“To Aetius, thrice Consul, the groans of the Britons.” And in the sequel of the letter they thus unfolded their woes:—“The barbarians drive us to the sea; the sea drives us back to the barbarians: between them we are exposed to two sorts of death; we are either slaughtered or drowned.” Yet, for all this, they could not obtain any help from him, as he was then engaged in most serious wars with Bledla and Attila, kings of the Huns. And though the year before this Bledla had been murdered by the treachery of his own brother Attila, yet Attila himself remained so intolerable an enemy to the Republic, that he ravaged almost all Europe, attacking and destroying cities and castles. At the same time there was a famine at Constantinople, and soon after a plague followed; moreover, a great part of the wall of that city, with fifty-seven towers, fell to the ground. Many cities also went to ruin, and the famine and pestilential state of the air destroyed thousands of men and cattle.

In the meantime, the aforesaid famine distressing the Britons more and more, and leaving to posterity a lasting memory of its mischievous effects, obliged many of them to submit themselves to the depredators; though others still held out, putting their trust in God, when human help failed. These continually made raids from the mountains, caves, and woods, and, at length, began to inflict severe losses on their enemies, who had been for so many years plundering the country. The bold Irish robbers thereupon returned home, intending to come again before long. The Picts then settled down in the farthest part of the island and afterwards remained there, but they did not fail to plunder and harass the Britons from time to time.

Now, when the ravages of the enemy at length abated, the island began to abound with such plenty of grain as had never been known in any age before; along with plenty, evil living increased, and this was immediately attended by the taint of all manner of crime; in particular, cruelty, hatred of truth, and love of falsehood; insomuch, that if any one among them happened to be milder than the rest, and more inclined to truth, all the rest abhorred and persecuted him unrestrainedly, as if he had been the enemy of Britain. Nor were the laity only guilty of these things, but even our Lord’s own flock, with its shepherds, casting off the easy yoke of Christ, gave themselves up to drunkenness, enmity, quarrels, strife, envy, and other such sins. In the meantime, on a sudden, a grievous plague fell upon that corrupt generation, which soon destroyed such numbers of them, that the living scarcely availed to bury the dead: yet, those that survived, could not be recalled from the spiritual death, which they had incurred through their sins, either by the death of their friends, or the fear of death. Whereupon, not long after, a more severe vengeance for their fearful crimes fell upon the sinful nation. They held a council to determine what was to be done, and where they should seek help to prevent or repel the cruel and frequent incursions of the northern nations; and in concert with their King Vortigern, it was unanimously decided to call the Saxons to their aid from beyond the sea, which, as the event plainly showed, was brought about by the Lord’s will, that evil might fall upon them for their wicked deeds.

In the year of our Lord 449, Marcian, the forty-sixth from Augustus, being made emperor with Valentinian, ruled the empire seven years. Then the nation of the Angles, or Saxons, being invited by the aforesaid king, arrived in Britain with three ships of war and had a place in which to settle assigned to them by the same king, in the eastern part of the island, on the pretext of fighting in defence of their country, whilst their real intentions were to conquer it. Accordingly they engaged with the enemy, who were come from the north to give battle, and the Saxons obtained the victory. When the news of their success and of the fertility of the country, and the cowardice of the Britons, reached their own home, a more considerable fleet was quickly sent over, bringing a greater number of men, and these, being added to the former army, made up an invincible force. The newcomers received of the Britons a place to inhabit among them, upon condition that they should wage war against their enemies for the peace and security of the country, whilst the Britons agreed to furnish them with pay. Those who came over were of the three most powerful nations of Germany—Saxons, Angles, and Jutes. From the Jutes are descended the people of Kent, and of the Isle of Wight, including those in the province of the West-Saxons who are to this day called Jutes, seated opposite to the Isle of Wight. From the Saxons, that is, the country which is now called Old Saxony, came the East-Saxons, the South-Saxons, and the West-Saxons. From the Angles, that is, the country which is called Angulus, and which is said, from that time, to have remained desert to this day, between the provinces of the Jutes and the Saxons, are descended the East-Angles, the Midland-Angles, the Mercians, all the race of the Northumbrians, that is, of those nations that dwell on the north side of the river Humber, and the other nations of the Angles. The first commanders are said to have been the two brothers Hengist and Horsa. Of these Horsa was afterwards slain in battle by the Britons, and a monument, bearing his name, is still in existence in the eastern parts of Kent. They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vitta, son of Vecta, son of Woden; from whose stock the royal race of many provinces trace their descent. In a short time, swarms of the aforesaid nations came over into the island, and the foreigners began to increase so much, that they became a source of terror to the natives themselves who had invited them. Then, having on a sudden entered into league with the Picts, whom they had by this time repelled by force of arms, they began to turn their weapons against their allies. At first, they obliged them to furnish a greater quantity of provisions; and, seeking an occasion of quarrel, protested, that unless more plentiful supplies were brought them, they would break the league, and ravage all the island; nor were they backward in putting their threats into execution. In short, the fire kindled by the hands of the pagans, proved God’s just vengeance for the crimes of the people; not unlike that which, being of old lighted by the Chaldeans, consumed the walls and all the buildings of Jerusalem. For here, too, through the agency of the pitiless conqueror, yet by the disposal of the just Judge, it ravaged all the neighbouring cities and country, spread the conflagration from the eastern to the western sea, without any opposition, and overran the whole face of the doomed island. Public as well as private buildings were overturned; the priests were everywhere slain before the altars; no respect was shown for office, the prelates with the people were destroyed with fire and sword; nor were there any left to bury those who had been thus cruelly slaughtered. Some of the miserable remnant, being taken in the mountains, were butchered in heaps. Others, spent with hunger, came forth and submitted themselves to the enemy, to undergo for the sake of food perpetual servitude, if they were not killed upon the spot. Some, with sorrowful hearts, fled beyond the seas. Others, remaining in their own country, led a miserable life of terror and anxiety of mind among the mountains, woods and crags.

When the army of the enemy, having destroyed and dispersed the natives, had returned home to their own settlements, the Britons began by degrees to take heart, and gather strength, sallying out of the lurking places where they had concealed themselves, and with one accord imploring the Divine help, that they might not utterly be destroyed. They had at that time for their leader, Ambrosius Aurelianus, a man of worth, who alone, by chance, of the Roman nation had survived the storm, in which his parents, who were of the royal race, had perished. Under him the Britons revived, and offering battle to the victors, by the help of God, gained the victory. From that day, sometimes the natives, and sometimes their enemies, prevailed, till the year of the siege of Badon-hill, when they made no small slaughter of those enemies, about forty-four years after their arrival in England. But of this hereafter.

The Life and Conversion of Edwin, King of Northumbria; the Faith of the East Angles

Thus wrote the aforesaid Pope Boniface for the salvation of King Edwin and his nation. But a heavenly vision, which the Divine Goodness was pleased once to reveal to this king, when he was in banishment at the court of Redwald, king of the Angles, was of no little use in urging him to receive and understand the doctrines of salvation. For when Paulinus perceived that it was a difficult task to incline the king’s proud mind to the humility of the way of salvation and the reception of the mystery of the life-giving Cross, and at the same time was employing the word of exhortation with men, and prayer to the Divine Goodness, for the salvation of Edwin and his subjects; at length, as we may suppose, it was shown him in spirit what the nature of the vision was that had been formerly revealed from Heaven to the king. Then he lost no time, but immediately admonished the king to perform the vow which he had made, when he received the vision, promising to fulfil it, if he should be delivered from the troubles of that time, and advanced to the throne.

The vision was this. When Ethelfrid, his predecessor, was persecuting him, he wandered for many years as an exile, hiding in divers places and kingdoms, and at last came to Redwald, beseeching him to give him protection against the snares of his powerful persecutor. Redwald willingly received him, and promised to perform what was asked of him. But when Ethelfrid understood that he had appeared in that province, and that he and his companions were hospitably entertained by Redwald, he sent messengers to bribe that king with a great sum of money to murder him, but without effect. He sent a second and a third time, offering a greater bribe each time, and, moreover, threatening to make war on him if his offer should be despised. Redwald, whether terrified by his threats, or won over by his gifts, complied with this request, and promised either to kill Edwin, or to deliver him up to the envoys. A faithful friend of his, hearing of this, went into his chamber, where he was going to bed, for it was the first hour of the night; and calling him out, told him what the king had promised to do with him, adding, “If, therefore, you are willing, I will this very hour conduct you out of this province, and lead you to a place where neither Redwald nor Ethelfrid shall ever find you.” He answered, “I thank you for your good will, yet I cannot do what you propose, and be guilty of being the first to break the compact I have made with so great a king, when he has done me no harm, nor shown any enmity to me; but, on the contrary, if I must die, let it rather be by his hand than by that of any meaner man. For whither shall I now fly, when I have for so many long years been a vagabond through all the provinces of Britain, to escape the snares of my enemies?” His friend went away; Edwin remained alone without, and sitting with a heavy heart before the palace, began to be overwhelmed with many thoughts, not knowing what to do, or which way to turn.

When he had remained a long time in silent anguish of mind, consumed with inward fire, on a sudden in the stillness of the dead of night he saw approaching a person, whose face and habit were strange to him, at sight of whom, seeing that he was unknown and unlooked for, he was not a little startled. The stranger coming close up, saluted him, and asked why he sat there in solitude on a stone troubled and wakeful at that time, when all others were taking their rest, and were fast asleep. Edwin, in his turn, asked, what it was to him, whether he spent the night within doors or abroad. The stranger, in reply, said, “Do not think that I am ignorant of the cause of your grief, your watching, and sitting alone without. For I know of a surety who you are, and why you grieve, and the evils which you fear will soon fall upon you. But tell me, what reward you would give the man who should deliver you out of these troubles, and persuade Redwald neither to do you any harm himself, nor to deliver you up to be murdered by your enemies.” Edwin replied, that he would give such an one all that he could in return for so great a benefit. The other further added, “What if he should also assure you, that your enemies should be destroyed, and you should be a king surpassing in power, not only all your own ancestors, but even all that have reigned before you in the English nation?” Edwin, encouraged by these questions, did not hesitate to promise that he would make a fitting return to him who should confer such benefits upon him. Then the other spoke a third time and said, “But if he who should truly foretell that all these great blessings are about to befall you, could also give you better and more profitable counsel for your life and salvation than any of your fathers or kindred ever heard, do you consent to submit to him, and to follow his wholesome guidance?” Edwin at once promised that he would in all things follow the teaching of that man who should deliver him from so many great calamities, and raise him to a throne.

Having received this answer, the man who talked to him laid his right hand on his head saying, “When this sign shall be given you, remember this present discourse that has passed between us, and do not delay the performance of what you now promise.” Having uttered these words, he is said to have immediately vanished. So the king perceived that it was not a man, but a spirit, that had appeared to him.

Whilst the royal youth still sat there alone, glad of the comfort he had received, but still troubled and earnestly pondering who he was, and whence he came, that had so talked to him, his aforesaid friend came to him, and greeting him with a glad countenance, “Rise,” said he, “go in; calm and put away your anxious cares, and compose yourself in body and mind to sleep; for the king’s resolution is altered, and he designs to do you no harm, but rather to keep his pledged faith; for when he had privately made known to the queen his intention of doing what I told you before, she dissuaded him from it, reminding him that it was altogether unworthy of so great a king to sell his good friend in such distress for gold, and to sacrifice his honour, which is more valuable than all other adornments, for the love of money.” In short, the king did as has been said, and not only refused to deliver up the banished man to his enemy’s messengers, but helped him to recover his kingdom. For as soon as the messengers had returned home, he raised a mighty army to subdue Ethelfrid; who, meeting him with much inferior forces, (for Redwald had not given him time to gather and unite all his power,) was slain on the borders of the kingdom of Mercia, on the east side of the river that is called Idle. In this battle, Redwald’s son, called Raegenheri, was killed. Thus Edwin, in accordance with the prophecy he had received, not only escaped the danger from his enemy, but, by his death, succeeded the king on the throne.

King Edwin, therefore, delaying to receive the Word of God at the preaching of Paulinus, and being wont for some time, as has been said, to sit many hours alone, and seriously to ponder with himself what he was to do, and what religion he was to follow, the man of God came to him one day, laid his right hand on his head, and asked, whether he knew that sign? The king, trembling, was ready to fall down at his feet, but he raised him up, and speaking to him with the voice of a friend, said, “Behold, by the gift of God you have escaped the hands of the enemies whom you feared. Behold, you have obtained of His bounty the kingdom which you desired. Take heed not to delay to perform your third promise; accept the faith, and keep the precepts of Him Who, delivering you from temporal adversity, has raised you to the honour of a temporal kingdom; and if, from this time forward, you shall be obedient to His will, which through me He signifies to you, He will also deliver you from the everlasting torments of the wicked, and make you partaker with Him of His eternal kingdom in heaven.”

The king, hearing these words, answered, that he was both willing and bound to receive the faith which Paulinus taught; but that he would confer about it with his chief friends and counsellors, to the end that if they also were of his opinion, they might all together be consecrated to Christ in the font of life. Paulinus consenting, the king did as he said; for, holding a council with the wise men, he asked of every one in particular what he thought of this doctrine hitherto unknown to them, and the new worship of God that was preached? The chief of his own priests, Coifi, immediately answered him, “O king, consider what this is which is now preached to us; for I verily declare to you what I have learnt beyond doubt, that the religion which we have hitherto professed has no virtue in it and no profit. For none of your people has applied himself more diligently to the worship of our gods than I; and yet there are many who receive greater favours from you, and are more preferred than I, and are more prosperous in all that they undertake to do or to get. Now if the gods were good for any thing, they would rather forward me, who have been careful to serve them with greater zeal. It remains, therefore, that if upon examination you find those new doctrines, which are now preached to us, better and more efficacious, we hasten to receive them without any delay.”

Another of the king’s chief men, approving of his wise words and exhortations, added thereafter: “The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.” The other elders and king’s counsellors, by Divine prompting, spoke to the same effect.

But Coifi added, that he wished more attentively to hear Paulinus discourse concerning the God Whom he preached. When he did so, at the king’s command, Coifi, hearing his words, cried out, “This long time I have perceived that what we worshipped was naught; because the more diligently I sought after truth in that worship, the less I found it. But now I freely confess, that such truth evidently appears in this preaching as can confer on us the gifts of life, of salvation, and of eternal happiness. For which reason my counsel is, O king, that we instantly give up to ban and fire those temples and altars which we have consecrated without reaping any benefit from them.” In brief, the king openly assented to the preaching of the Gospel by Paulinus, and renouncing idolatry, declared that he received the faith of Christ: and when he inquired of the aforesaid high priest of his religion, who should first desecrate the altars and temples of their idols, with the precincts that were about them, he answered, “I; for who can more fittingly than myself destroy those things which I worshipped in my folly, for an example to all others, through the wisdom which has been given me by the true God?” Then immediately, in contempt of his vain superstitions, he desired the king to furnish him with arms and a stallion, that he might mount and go forth to destroy the idols; for it was not lawful before for the high priest either to carry arms, or to ride on anything but a mare. Having, therefore, girt a sword about him, with a spear in his hand, he mounted the king’s stallion, and went his way to the idols. The multitude, beholding it, thought that he was mad; but as soon as he drew near the temple he did not delay to desecrate it by casting into it the spear which he held; and rejoicing in the knowledge of the worship of the true God, he commanded his companions to tear down and set on fire the temple, with all its precincts. This place where the idols once stood is still shown, not far from York, to the eastward, beyond the river Derwent, and is now called Godmunddingaham, where the high priest, by the inspiration of the true God, profaned and destroyed the altars which he had himself consecrated.

King Edwin, therefore, with all the nobility of the nation, and a large number of the common sort, received the faith, and the washing of holy regeneration, in the eleventh year of his reign, which is the year of our Lord 627, and about one hundred and eighty after the coming of the English into Britain. He was baptized at York, on the holy day of Easter, being the 12th of April, in the church of St. Peter the Apostle, which he himself had built of timber there in haste, whilst he was a catechumen receiving instruction in order to be admitted to baptism. In that city also he bestowed upon his instructor and bishop, Paulinus, his episcopal see. But as soon as he was baptized, he set about building, by the direction of Paulinus, in the same place a larger and nobler church of stone, in the midst whereof the oratory which he had first erected should be enclosed. Having, therefore, laid the foundation, he began to build the church square, encompassing the former oratory. But before the walls were raised to their full height, the cruel death of the king left that work to be finished by Oswald his successor. Paulinus, for the space of six years from this time, that is, till the end of the king’s reign, with his consent and favour, preached the Word of God in that country, and as many as were foreordained to eternal life believed and were baptized. Among them were Osfrid and Eadfrid, King Edwin’s sons who were both born to him, whilst he was in banishment, of Quenburga, the daughter of Cearl, king of the Mercians.

Afterwards other children of his, by Queen Ethelberg, were baptized, Ethelhun and his daughter Ethelthryth, and another, Wuscfrea, a son; the first two were snatched out of this life whilst they were still in the white garments of the newly-baptized, and buried in the church at York. Yffi, the son of Osfrid, was also baptized, and many other noble and royal persons. So great was then the fervour of the faith, as is reported, and the desire for the laver of salvation among the nation of the Northumbrians, that Paulinus at a certain time coming with the king and queen to the royal township, which is called Adgefrin, stayed there with them thirty-six days, fully occupied in catechizing and baptizing; during which days, from morning till night, he did nothing else but instruct the people resorting from all villages and places, in Christ’s saving Word; and when they were instructed, he washed them with the water of absolution in the river Glen, which is close by. This township, under the following kings, was abandoned, and another was built instead of it, at the place called Maelmin.

These things happened in the province of the Bernicians; but in that of the Deiri also, where he was wont often to be with the king, he baptized in the river Swale, which runs by the village of Cataract; for as yet oratories, or baptisteries, could not be built in the early infancy of the Church in those parts. But in Campodonum, where there was then a royal township, he built a church which the pagans, by whom King Edwin was slain, afterwards burnt, together with all the place. Instead of this royal seat the later kings built themselves a township in the country called Loidis. But the altar, being of stone, escaped the fire and is still preserved in the monastery of the most reverend abbot and priest, Thrydwulf, which is in the forest of Elmet.

Edwin was so zealous for the true worship, that he likewise persuaded Earpwald, king of the East Angles, and son of Redwald, to abandon his idolatrous superstitions, and with his whole province to receive the faith and mysteries of Christ. And indeed his father Redwald had long before been initiated into the mysteries of the Christian faith in Kent, but in vain; for on his return home, he was seduced by his wife and certain perverse teachers, and turned aside from the sincerity of the faith; and thus his latter state was worse than the former; so that, like the Samaritans of old, he seemed at the same time to serve Christ and the gods whom he served before; and in the same temple he had an altar for the Christian Sacrifice, and another small one at which to offer victims to devils. Aldwulf, king of that same province, who lived in our time, testifies that this temple had stood until his time, and that he had seen it when he was a boy. The aforesaid King Redwald was noble by birth, though ignoble in his actions, being the son of Tytilus, whose father was Uuffa, from whom the kings of the East Angles are called Uuffings.

Earpwald, not long after he had embraced the Christian faith, was slain by one Ricbert, a pagan; and from that time the province was in error for three years, till Sigbert succeeded to the kingdom, brother to the same Earpwald, a most Christian and learned man, who was banished, and went to live in Gaul during his brother’s life, and was there initiated into the mysteries of the faith, whereof he made it his business to cause all his province to partake as soon as he came to the throne. His exertions were nobly promoted by Bishop Felix, who, coming to Honorius, the archbishop, from the parts of Burgundy, where he had been born and ordained, and having told him what he desired, was sent by him to preach the Word of life to the aforesaid nation of the Angles. Nor were his good wishes in vain; for the pious labourer in the spiritual field reaped therein a great harvest of believers, delivering all that province (according to the inner signification of his name) from long iniquity and unhappiness, and bringing it to the faith and works of righteousness, and the gifts of everlasting happiness. He had the see of his bishopric appointed him in the city Dommoc, and having presided over the same province with pontifical authority seventeen years, he ended his days there in peace.

Paulinus also preached the Word to the province of Lindsey, which is the first on the south side of the river Humber, stretching as far as the sea; and he first converted to the Lord the reeve of the city of Lincoln, whose name was Blaecca, with his whole house. He likewise built, in that city, a stone church of beautiful workmanship; the roof of which has either fallen through long neglect, or been thrown down by enemies, but the walls are still to be seen standing, and every year miraculous cures are wrought in that place, for the benefit of those who have faith to seek them. In that church, when Justus had departed to Christ, Paulinus consecrated Honorius bishop in his stead, as will be hereafter mentioned in its proper place. A certain priest and abbot of the monastery of Peartaneu, a man of singular veracity, whose name was Deda, told me concerning the faith of this province that an old man had informed him that he himself had been baptized at noon-day, by Bishop Paulinus, in the presence of King Edwin, and with him a great multitude of the people, in the river Trent, near the city, which in the English tongue is called Tiouulfingacaestir; and he was also wont to describe the person of the same Paulinus, saying that he was tall of stature, stooping somewhat, his hair black, his visage thin, his nose slender and aquiline, his aspect both venerable and awe-inspiring. He had also with him in the ministry, James, the deacon, a man of zeal and great fame in Christ and in the church, who lived even to our days.

It is told that there was then such perfect peace in Britain, wheresoever the dominion of King Edwin extended, that, as is still proverbially said, a woman with her new-born babe might walk throughout the island, from sea to sea, without receiving any harm. That king took such care for the good of his nation, that in several places where he had seen clear springs near the highways, he caused stakes to be fixed, with copper drinking-vessels hanging on them, for the refreshment of travellers; nor durst any man touch them for any other purpose than that for which they were designed, either through the great dread they had of the king, or for the affection which they bore him. His dignity was so great throughout his dominions, that not only were his banners borne before him in battle, but even in time of peace, when he rode about his cities, townships, or provinces, with his thegns, the standard-bearer was always wont to go before him. Also, when he walked anywhere along the streets, that sort of banner which the Romans call Tufa, and the English, Thuuf, was in like manner borne before him.

Abbes Hild of Whitby; the Miraculous Poet Caedmon

In the year after this, that is the year of our Lord 680, the most religious handmaid of Christ, Hilda, abbess of the monastery that is called Streanaeshalch, as we mentioned above, after having done many heavenly deeds on earth, passed thence to receive the rewards of the heavenly life, on the 17th of November, at the age of sixty-six years. Her life falls into two equal parts, for the first thirty-three years of it she spent living most nobly in the secular habit; and still more nobly dedicated the remaining half to the Lord in the monastic life. For she was nobly born, being the daughter of Hereric, nephew to King Edwin, and with that king she also received the faith and mysteries of Christ, at the preaching of Paulinus, of blessed memory, the first bishop of the Northumbrians, and preserved the same undefiled till she attained to the vision of our Lord in Heaven.

When she had resolved to quit the secular habit, and to serve Him alone, she withdrew into the province of the East Angles, for she was allied to the king there; being desirous to cross over thence into Gaul, forsaking her native country and all that she had, and so to live a stranger for our Lord’s sake in the monastery of Cale, that she might the better attain to the eternal country in heaven. For her sister Heresuid, mother to Aldwulf, king of the East Angles, was at that time living in the same monastery, under regular discipline, waiting for an everlasting crown; and led by her example, she continued a whole year in the aforesaid province, with the design of going abroad; but afterwards, Bishop Aidan recalled her to her home, and she received land to the extent of one family on the north side of the river Wear; where likewise for a year she led a monastic life, with very few companions.

After this she was made abbess in the monastery called Heruteu, which monastery had been founded, not long before, by the pious handmaid of Christ, Heiu, who is said to have been the first woman in the province of the Northumbrians who took upon her the vows and habit of a nun, being consecrated by Bishop Aidan; but she, soon after she had founded that monastery, retired to the city of Calcaria, which is called Kaelcacaestir by the English, and there fixed her dwelling. Hilda, the handmaid of Christ, being set over that monastery, began immediately to order it in all things under a rule of life, according as she had been instructed by learned men; for Bishop Aidan, and others of the religious that knew her, frequently visited her and loved her heartily, and diligently instructed her, because of her innate wisdom and love of the service of God.

When she had for some years governed this monastery, wholly intent upon establishing a rule of life, it happened that she also undertook either to build or to set in order a monastery in the place called Streanaeshalch, and this work which was laid upon her she industriously performed; for she put this monastery under the same rule of monastic life as the former; and taught there the strict observance of justice, piety, chastity, and other virtues, and particularly of peace and charity; so that, after the example of the primitive Church, no one there was rich, and none poor, for they had all things common, and none had any private property. Her prudence was so great, that not only meaner men in their need, but sometimes even kings and princes, sought and received her counsel; she obliged those who were under her direction to give so much time to reading of the Holy Scriptures, and to exercise themselves so much in works of justice, that many might readily be found there fit for the priesthood and the service of the altar.

Indeed we have seen five from that monastery who afterwards became bishops, and all of them men of singular merit and sanctity, whose names were Bosa, Aetla, Oftfor, John, and Wilfrid. Of the first we have said above that he was consecrated bishop of York; of the second, it may be briefly stated that he was appointed bishop of Dorchester. Of the last two we shall tell hereafter, that the former was ordained bishop of Hagustald, the other of the church of York; of the third, we may here mention that, having applied himself to the reading and observance of the Scriptures in both the monasteries of the Abbess Hilda, at length being desirous to attain to greater perfection, he went into Kent, to Archbishop Theodore, of blessed memory; where having spent some time in sacred studies, he resolved to go to Rome also, which, in those days, was esteemed a very salutary undertaking. Returning thence into Britain, he took his way into the province of the Hwiccas, where King Osric then ruled, and continued there a long time, preaching the Word of faith, and showing an example of good life to all that saw and heard him. At that time, Bosel, the bishop of that province, laboured under such weakness of body, that he could not himself perform episcopal functions; for which reason, Oftfor was, by universal consent, chosen bishop in his stead, and by order of King Ethelred, consecrated by Bishop Wilfrid, of blessed memory, who was then Bishop of the Midland Angles, because Archbishop Theodore was dead, and no other bishop ordained in his place. A little while before, that is, before the election of the aforesaid man of God, Bosel, Tatfrid, a man of great industry and learning, and of excellent ability, had been chosen bishop for that province, from the monastery of the same abbess, but had been snatched away by an untimely death, before he could be ordained.

Thus this handmaid of Christ, the Abbess Hilda, whom all that knew her called Mother, for her singular piety and grace, was not only an example of good life, to those that lived in her monastery, but afforded occasion of amendment and salvation to many who lived at a distance, to whom the blessed fame was brought of her industry and virtue. For it was meet that the dream of her mother, Bregusuid, during her infancy, should be fulfilled. Now Bregusuid, at the time that her husband, Hereric, lived in banishment, under Cerdic, king of the Britons, where he was also poisoned, fancied, in a dream, that he was suddenly taken away from her and she was seeking for him most carefully, but could find no sign of him anywhere. After an anxious search for him, all at once she found a most precious necklace under her garment, and whilst she was looking on it very attentively, it seemed to shine forth with such a blaze of light that it filled all Britain with the glory of its brilliance. This dream was doubtless fulfilled in her daughter that we speak of, whose life was an example of the works of light, not only blessed to herself, but to many who desired to live aright.

When she had governed this monastery many years, it pleased Him Who has made such merciful provision for our salvation, to give her holy soul the trial of a long infirmity of the flesh, to the end that, according to the Apostle’s example, her virtue might be made perfect in weakness. Struck down with a fever, she suffered from a burning heat, and was afflicted with the same trouble for six years continually; during all which time she never failed either to return thanks to her Maker, or publicly and privately to instruct the flock committed to her charge; for taught by her own experience she admonished all men to serve the Lord dutifully, when health of body is granted to them, and always to return thanks faithfully to Him in adversity, or bodily infirmity. In the seventh year of her sickness, when the disease turned inwards, her last day came, and about cockcrow, having received the voyage provision of Holy Housel, and called together the handmaids of Christ that were within the same monastery, she admonished them to preserve the peace of the Gospel among themselves, and with all others; and even as she spoke her words of exhortation, she joyfully saw death come, or, in the words of our Lord, passed from death unto life.

That same night it pleased Almighty God, by a manifest vision, to make known her death in another monastery, at a distance from hers, which she had built that same year, and which is called Hacanos. There was in that monastery, a certain nun called Begu, who, having dedicated her virginity to the Lord, had served Him upwards of thirty years in the monastic life. This nun was resting in the dormitory of the sisters, when on a sudden she heard in the air the well-known sound of the bell, which used to awake and call them to prayers, when any one of them was taken out of this world, and opening her eyes, as she thought, she saw the roof of the house open, and a light shed from above filling all the place. Looking earnestly upon that light, she saw the soul of the aforesaid handmaid of God in that same light, being carried to heaven attended and guided by angels. Then awaking, and seeing the other sisters lying round about her, she perceived that what she had seen had been revealed to her either in a dream or a vision; and rising immediately in great fear, she ran to the virgin who then presided in the monastery in the place of the abbess, and whose name was Frigyth, and, with many tears and lamentations, and heaving deep sighs, told her that the Abbess Hilda, mother of them all, had departed this life, and had in her sight ascended to the gates of eternal light, and to the company of the citizens of heaven, with a great light, and with angels for her guides. Frigyth having heard it, awoke all the sisters, and calling them to the church, admonished them to give themselves to prayer and singing of psalms, for the soul of their mother; which they did earnestly during the remainder of the night; and at break of day, the brothers came with news of her death, from the place where she had died. They answered that they knew it before, and then related in order how and when they had learnt it, by which it appeared that her death had been revealed to them in a vision that same hour in which the brothers said that she had died. Thus by a fair harmony of events Heaven ordained, that when some saw her departure out of this world, the others should have knowledge of her entrance into the eternal life of souls. These monasteries are about thirteen miles distant from each other.

It is also told, that her death was, in a vision, made known the same night to one of the virgins dedicated to God, who loved her with a great love, in the same monastery where the said handmaid of God died. This nun saw her soul ascend to heaven in the company of angels; and this she openly declared, in the very same hour that it happened, to those handmaids of Christ that were with her; and aroused them to pray for her soul, even before the rest of the community had heard of her death. The truth of which was known to the whole community in the morning. This same nun was at that time with some other handmaids of Christ, in the remotest part of the monastery, where the women who had lately entered the monastic life were wont to pass their time of probation, till they were instructed according to rule, and admitted into the fellowship of the community.

There was in the monastery of this abbess a certain brother, marked in a special manner by the grace of God, for he was wont to make songs of piety and religion, so that whatever was expounded to him out of Scripture, he turned ere long into verse expressive of much sweetness and penitence, in English, which was his native language. By his songs the minds of many were often fired with contempt of the world, and desire of the heavenly life. Others of the English nation after him attempted to compose religious poems, but none could equal him, for he did not learn the art of poetry from men, neither was he taught by man, but by God’s grace he received the free gift of song, for which reason he never could compose any trivial or vain poem, but only those which concern religion it behoved his religious tongue to utter. For having lived in the secular habit till he was well advanced in years, he had never learned anything of versifying; and for this reason sometimes at a banquet, when it was agreed to make merry by singing in turn, if he saw the harp come towards him, he would rise up from table and go out and return home.

Once having done so and gone out of the house where the banquet was, to the stable, where he had to take care of the cattle that night, he there composed himself to rest at the proper time. Thereupon one stood by him in his sleep, and saluting him, and calling him by his name, said, “Cædmon, sing me something.” But he answered, “I cannot sing, and for this cause I left the banquet and retired hither, because I could not sing.” Then he who talked to him replied, “Nevertheless thou must needs sing to me.” “What must I sing?” he asked. “Sing the beginning of creation,” said the other. Having received this answer he straightway began to sing verses to the praise of God the Creator, which he had never heard, the purport whereof was after this manner: “Now must we praise the Maker of the heavenly kingdom, the power of the Creator and His counsel, the deeds of the Father of glory. How He, being the eternal God, became the Author of all wondrous works, Who being the Almighty Guardian of the human race, first created heaven for the sons of men to be the covering of their dwelling place, and next the earth.” This is the sense but not the order of the words as he sang them in his sleep; for verses, though never so well composed, cannot be literally translated out of one language into another without loss of their beauty and loftiness. Awaking from his sleep, he remembered all that he had sung in his dream, and soon added more after the same manner, in words which worthily expressed the praise of God.

In the morning he came to the reeve who was over him, and having told him of the gift he had received, was conducted to the abbess, and bidden, in the presence of many learned men, to tell his dream, and repeat the verses, that they might all examine and give their judgement upon the nature and origin of the gift whereof he spoke. And they all judged that heavenly grace had been granted to him by the Lord. They expounded to him a passage of sacred history or doctrine, enjoining upon him, if he could, to put it into verse. Having undertaken this task, he went away, and returning the next morning, gave them the passage he had been bidden to translate, rendered in most excellent verse. Whereupon the abbess, joyfully recognizing the grace of God in the man, instructed him to quit the secular habit, and take upon him monastic vows; and having received him into the monastery, she and all her people admitted him to the company of the brethren, and ordered that he should be taught the whole course of sacred history. So he, giving ear to all that he could learn, and bearing it in mind, and as it were ruminating, like a clean animal, turned it into most harmonious verse; and sweetly singing it, made his masters in their turn his hearers. He sang the creation of the world, the origin of man, and all the history of Genesis, the departure of the children of Israel out of Egypt, their entrance into the promised land, and many other histories from Holy Scripture; the Incarnation, Passion, Resurrection of our Lord, and His Ascension into heaven; the coming of the Holy Ghost, and the teaching of the Apostles; likewise he made many songs concerning the terror of future judgement, the horror of the pains of hell, and the joys of heaven; besides many more about the blessings and the judgements of God, by all of which he endeavoured to draw men away from the love of sin, and to excite in them devotion to well-doing and perseverance therein. For he was a very religious man, humbly submissive to the discipline of monastic rule, but inflamed with fervent zeal against those who chose to do otherwise; for which reason he made a fair ending of his life.

For when the hour of his departure drew near, it was preceded by a bodily infirmity under which he laboured for the space of fourteen days, yet it was of so mild a nature that he could talk and go about the whole time. In his neighbourhood was the house to which those that were sick, and like to die, were wont to be carried. He desired the person that ministered to him, as the evening came on of the night in which he was to depart this life, to make ready a place there for him to take his rest. The man, wondering why he should desire it, because there was as yet no sign of his approaching death, nevertheless did his bidding. When they had lain down there, and had been conversing happily and pleasantly for some time with those that were in the house before, and it was now past midnight, he asked them, whether they had the Eucharist within? They answered, “What need of the Eucharist? for you are not yet appointed to die, since you talk so merrily with us, as if you were in good health.” “Nevertheless,” said he, “bring me the Eucharist.” Having received It into his hand, he asked, whether they were all in charity with him, and had no complaint against him, nor any quarrel or grudge. They answered, that they were all in perfect charity with him, and free from all anger; and in their turn they asked him to be of the same mind towards them. He answered at once, “I am in charity, my children, with all the servants of God.” Then strengthening himself with the heavenly Viaticum, he prepared for the entrance into another life, and asked how near the time was when the brothers should be awakened to sing the nightly praises of the Lord? They answered, “It is not far off.” Then he said, “It is well, let us await that hour;”and signing himself with the sign of the Holy Cross, he laid his head on the pillow, and falling into a slumber for a little while, so ended his life in silence.

Thus it came to pass, that as he had served the Lord with a simple and pure mind, and quiet devotion, so he now departed to behold His Presence, leaving the world by a quiet death; and that tongue, which had uttered so many wholesome words in praise of the Creator, spake its last words also in His praise, while he signed himself with the Cross, and commended his spirit into His hands; and by what has been here said, he seems to have had foreknowledge of his death.

Caedmon’s Hymn

You can also listen to this hymn at Librivox:

Now [we] must honour the guardian of heaven,

the might of the architect, and his purpose,

the work of the father of glory

as he, the eternal lord, established the beginning of wonders;

he first created for the children of men

heaven as a roof, the holy creator

Then the guardian of mankind,

the eternal lord, afterwards appointed the middle earth

the lands for men, the Lord almighty.

Source Text:

Bede. “Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England,” trans. by A.M. Seller, is licensed under no known copyright.