21 CONTEXTS: Crises of the 14th Century

Introduction

by Allegra Villarreal

Britain endured four major “crises” during an exceptionally challenging period that brought about great change on the island itself and Europe as a whole. The first of these was the “Great Famine” (1315-1318), caused by three years of torrential rains that flooded farms throughout Europe, leaving hunger, disease and universal suffering in its wake.

The second was a series of territorial conflicts between Britain and France that we now collectively know as the “Hundred Years’ War.” English kings, since the times of Henry II, held lands in France and sought to expand their territories across the English Channel; when French nobles refused to recognize Edward III’s claim to the French throne, a war broke out that would last 116 years in total. In the excerpts below, there is a description of two memorable battles: The Battle of Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) where the expert use of the longbow and leadership of Edward the Black Prince ensured English victory. The English would go on to have additional battlefield victories, notably at Agincourt in 1415, but by 1450 the tides had turned and, when all was said and done, the borders of modern-day France began to take shape as the English retreated back to their island.

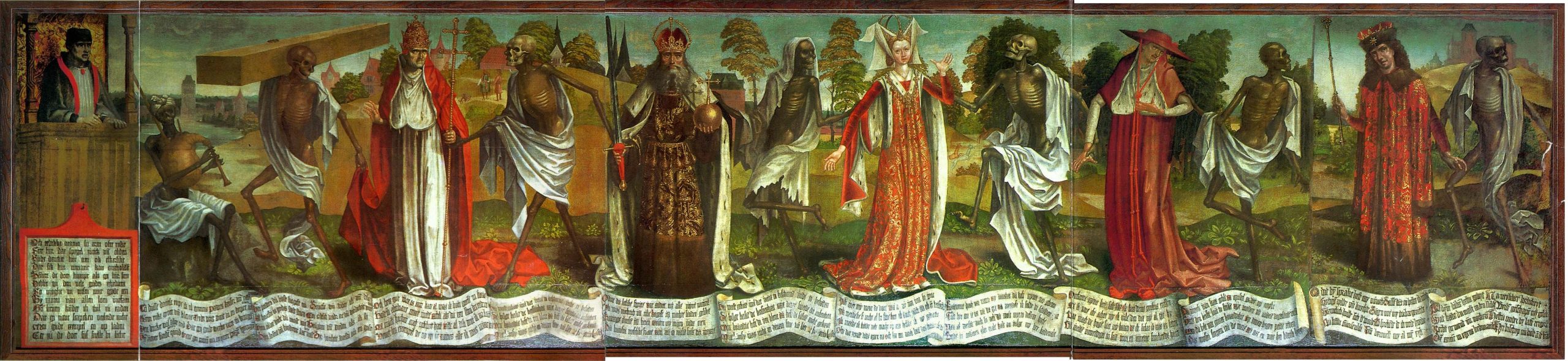

A devastating epidemic, known today as the “Black Plague” or “Black Death” swept across Europe in the 1340s; by 1348, reports emerged that it had made its way to the British Isles. Ultimately, a third of the population on the island succumbed and it would take the better part of a century for the population to reach its pre-plague numbers. This triggered a demographic shift and labor shortage that the government attempted to address through wage and price control (as seen in the readings below) but ultimately led to the decline of the feudal order and the emergence of a middle class.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that the Hundred Years’ War and the Black Death, which necessarily brought about an enormous upheaval of the social order, would ultimately lead to the Uprising of 1381 (or the “Peasant’s Revolt” as it is more popularly known). In response to Parliament’s institution of a new poll tax (imposed on all adults in the kingdom to fund the ongoing wars with France), a widespread rebellion broke out–the first by commoners in the nation’s history. Ultimately, the rebellion was violently suppressed but it did give peasants new leverage to negotiate the terms of their labor: no longer would commoners tolerate outright servitude but rather a system of lease-hold agreements flourished whereby peasants paid rent on the land they tilled.

The Great Famine

from Anonymous (the “Monk of Malmesbury”), Life of Edward the Second

In this parliament [of February–March, 1315], because merchants going about the country selling victuals charged excessively, the earls and barons, looking to the welfare of the state, appointed a remedy for this malady; they ordained a fixed price for oxen, pigs and sheep, for fowls, chickens, and pigeons, and for other common foods. … These matters were published throughout the land, and publicly proclaimed in shire courts and boroughs. …

By certain portents the hand of God appears to be raised against us. For in the past year there was such plentiful rain that men could scarcely harvest the corn or bring it safely to the barn. In the present year worse has happened. For the floods of rain have rotted almost all the seed, so that the prophecy of Isaiah might seem now to be fulfilled; for he says that “ten acres of vineyard shall yield one little measure and thirty bushels of seed shall yield three bushels”: and in many places the hay lay so long under water that it could neither be mown nor gathered. Sheep generally died and other animals were killed in a sudden plague. It is greatly to be feared that if the Lord finds us incorrigible after these visitations, he will destroy at once both men and beasts; and I firmly believe that unless the English Church had interceded for us, we should have perished long ago. … After the feast of Easter [in 1316] the dearth of corn was much increased. Such a scarcity has not been seen in our time in England, nor heard of for a hundred years. For a measure of wheat sold in London and the neighboring places for forty pence, and in other less thickly populated parts of the country thirty pence was a com- mon price. Indeed during this time of scarcity a great famine appeared, and after the famine came a severe pestilence, of which many thousands died in many places. I have even heard it said by some, that in Northumbria dogs and horses and other unclean things were eaten. For there, on account of the frequent raids of the Scots, work is more irksome, as the accursed Scots despoil the people daily of their food. Alas, poor England! You who once helped other lands from your abundance, now poor and needy are forced to beg. Fruitful land is turned into a salt- marsh; the inclemency of the weather destroys the fatness of the land; corn is sown and tares are brought forth. All this comes from the wickedness of the inhabitants. Spare, O Lord, spare thy people! For we are a scorn and a derision to them who are around us. Yet those who are wise in astrology say that these storms in the heavens have happened naturally; for Saturn, cold and heedless, brings rough weather that is useless to the seed; in the ascendant now for three years he has completed his course, and mild Jupiter duly succeeds him. Under Jupiter these floods of rain will cease, the valleys will grow rich in corn, and the fields will be filled with abundance. For the Lord shall give that which is good and our land shall yield her increase …

[In 1318] the dearth that had so long plagued us ceased, and England became fruitful with a manifold abundance of good things. A measure of wheat, which the year before was sold for forty pence, was now freely offered to the buyer for sixpence …

The Hundred Years’ War

from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles

The lord Moyne said [to the king of France], “Sir, I will speak, since it pleases you to order me, but with the assistance of my companions. We have advanced far enough to reconnoitre your enemies. Know, then, that they are drawn up in three battalions and are awaiting you. I would advise, for my part (submitting, however, to better counsel), that you halt your army here and quarter them for the night; for before the rear shall come up and the army be properly drawn out, it will be very late. Your men will be tired and in disorder, while they will find your enemies fresh and properly arrayed. On the morrow, you may draw up your army more at your ease and may reconnoitre at leisure on what part it will be most advantageous to begin the attack; for, be assured, they will wait for you.”

The king commanded that it should be so done; and the two marshals rode, one towards the front, and the other to the rear, crying out, “Halt banners, in the name of God and St. Denis.” Those that were in the front halted; but those behind said they would not halt until they were as far forward as the front. When the front perceived the rear pushing on, they pushed forward; and neither the king nor the marshals could stop them, but they marched on without any order until they came in sight of their enemies. As soon as the foremost rank saw them, they fell back at once in great disorder, which alarmed those in the rear, who thought they had been fighting. There was then space and room enough for them to have passed forward, had they been willing to do so. Some did so, but others remained behind.

All the roads between Abbeville and Crécy were covered with common people, who, when they had come within three leagues of their enemies, drew their swords, crying out, “Kill, kill”; and with them were many great lords who were eager to make show of their courage. There is no man, unless he had been present, who can imagine, or describe truly, the confusion of that day, especially the bad management and disorder of the French, whose troops were beyond number.

The English, who were drawn up in three divisions and seated on the ground, on seeing their enemies advance, arose boldly and fell into their ranks. That of the Prince was the first to do so, whose archers were formed in the manner of a portcullis, or harrow, and the men-at-arms in the rear.1 The earls of Northampton and Arundel, who commanded the second division, had posted themselves in good order on his wing to assist and succor the Prince, if necessary.

You must know that these kings, dukes, earls, barons, and lords of France did not advance in any regular order, but one after the other, or in any way most pleasing to themselves. As soon as the King of France came in sight of the English his blood began to boil, and he cried out to his marshals, “Order the Genoese forward, and begin the battle, in the name of God and St. Denis.” There were about fifteen thousand Genoese cross-bowmen; but they were quite fatigued, having marched on foot that day six leagues, completely armed, and with their cross-bows. They told the consta- ble that they were not in a fit condition to do any great things that day in battle. The Earl of Alençon, hearing this, said, “This is what one gets by employing such scoundrels, who fail when there is any need for them.”

During this time a heavy rain fell, accompanied by thunder and a very terrible eclipse of the sun; and before this rain a great flight of crows hovered in the air over all those battalions, making a loud noise. Shortly afterwards it cleared up and the sun shone very brightly; but the French- men had it in their faces, and the English at their backs.

When the Genoese were somewhat in order they approached the English and set up a loud shout in order to frighten them; but the latter remained quite still and did not seem to hear it. They then set up a second shout and advanced a little forward; but the English did not move. They hooted a third time, advancing with their cross-bows presented, and began to shoot. The English archers then advanced one step forward and shot their arrows with such force and quickness that it seemed as if it snowed.

When the Genoese felt these arrows, which pierced their arms, heads, and through their armor, some of them cut the strings of their cross-bows, others flung them on the ground, and all turned about and retreated, quite discomfited. The French had a large body of men- at-arms on horseback, richly dressed, to support the Genoese. The King of France, seeing them fall back, cried out, “Kill me those scoundrels; for they stop up our road, without any reason.” You would then have seen the above-mentioned men-at-arms lay about them, killing all that they could of these runaways.

The English continued shooting as vigorously and quickly as before. Some of their arrows fell among the horsemen, who were sumptuously equipped, and, killing and wounding many, made them caper and fall among the Genoese, so that they were in such confusion they could never rally again. In the English army there were some Cornish- and Welshmen on foot who had armed themselves with large knives. These, advancing through the ranks of the men-at-arms and archers, who made way for them, came upon the French when they were in this danger and, falling upon earls, barons, knights and squires, slew many, at which the king of England was afterwards much exasperated.

Late after vespers, the King of France had not more about him than sixty men, everyone included. Sir John of Hainault, who was of the number, had once remounted the king; for the latter’s horse had been killed under him by an arrow. He said to the king, “Sir, retreat while you have an opportunity, and do not expose yourself so needlessly. If you have lost this battle, another time you will be the conqueror.” After he had said this, he took the bridle of the king’s horse and led him off by force; for he had before entreated him to retire.

The king rode on until he came to the castle of La Broyes, where he found the gates shut, for it was very dark. The king ordered the governor of it to be summoned. He came upon the battlements and asked who it was that called at such an hour. The king answered, “Open, open, governor; it is the fortune of France.” The governor, hearing the king’s voice, immediately descended, opened the gate, and let down the bridge. The king and his company entered the castle; but he had with him only five barons—Sir John Hainault, the lord Charles of Montmorency, the lord of Beaujeu, the lord of Aubigny, and the lord of Montfort. The king would not bury himself in such a place as that, but, having taken some refreshments, set out again with his attendants about midnight, and rode on, under the direction of guides who were well acquainted with the country, until, about daybreak, he came to Amiens, where he halted.

This Saturday the English never quitted their ranks in pursuit of anyone, but remained on the field, guarding their positions and defending themselves against all who attacked them. The battle was ended at the hour of vespers. When, on this Saturday night, the English heard no more hooting or shouting, nor any more crying out to particular lords, or their banners, they looked upon the field as their own and their enemies as beaten.

They made great fires and lighted torches because of the darkness of the night. King Edward [III] then came down from his post, who all that day had not put on his helmet, and, with his whole battalion, advanced to the prince of Wales [Edward the “Black Prince”], whom he embraced in his arms and kissed, and said, “Sweet son, God give you good preference. You are my son, for most loyally have you acquitted yourself this day. You are worthy to be a sovereign.” The prince bowed down very low and humbled himself, giving all honor to the king his father.

The English, during the night, made frequent thanksgivings to the Lord for the happy outcome of the day, and without rioting; for the King had forbidden all riot or noise.

from Prince Edward’s Letter to the People of London (1356)

Very dear and very much beloved: As concerning news in the parts where we are, know that since the time when we informed our most dread lord and father, the King [Edward III], that it was our purpose to ride forth against the enemies in the parts of France, we took our road through the country of Périgueux and of Limousin, and straight on towards Bourges in Vienne, where we expected to have found the [French] king’s son, the count of Poitiers. …

And then our people pursued them as far as Chauvigny, full three leagues further; for which reason we were obliged that day to take up our quarters as near to that place as we could, that we might collect our men. And on the morrow we took our road straight towards the king, and sent out our scouts, who found him with his army; set himself in battle array at one league from Poitiers, in the fields; and we went as near to him as we could take up our post, we ourselves on foot and in battle array, and ready to fight with him.

Where came the said Cardinal [Talleyrand], requesting very earnestly for a little respite, that so there might parley together certain persons of either side, and so attempt to bring about an understanding and good peace; the which he undertook that he would bring about to a good end. Whereupon we took counsel, and granted him his request; upon which there were ordered certain persons of the one side and the other to treat upon this matter; which treating was of no effect. And then the said Cardinal wished to obtain a truce, by way of putting off the battle at his pleasure; to which truce we would not assent. And the French asked that certain knights on the one side and the other should take equal shares, so that the battle might n ot in any mann er fail: and in such manner was that day delayed; and the battalions on the one side and the other remained all night, each one in its place, and until the morrow, about half prime; and as to some troops that were between the said main armies, neither would give any advantage in commencing the attack upon the other. And for default of victuals, as well as for other reasons, it was agreed that we should take our way, flanking them, in such manner that if they wished for battle or to draw towards us, in a place that was not very much to our disadvantage, we should be the first; and so forthwith it was done. Whereupon battle was joined, on [September 19,] the eve of the day before St. Matthew; and, God be praised for it, the enemy was discomfited, and the King was taken, and his son; and a great number of other great people were both taken and slain; as our very dear bachelor Messire Neele Lorraine, our chamberlain, the bearer hereof, who has very full knowledge thereon, will know how to inform and show you more fully, as we are not able to write to you. To him you should give full faith and credence; and may our Lord have you in his keeping. Given under our privy seal, at Bordeaux, the 22nd day of October.

The Black Death

from Ralph of Shrewsbury, Letter (17 August 1348)

… Since the disaster of such a pestilence has come from the eastern parts to a neighboring kingdom, it is greatly to be feared, and being greatly to be feared, it is to be prayed devoutly and without ceasing that such a pestilence not extend its poisonous growth to the inhabitants of this kingdom, and torment and consume them.

Therefore, to each and all of you we mandate, with firm enjoining, that in your churches you publicly announce this present mandate in the vulgar tongue at opportune times, and that in the bowels of Jesus Christ you exhort your subordinates—regular, secular, parishioners, and others—or have them exhorted by others, to appear before the Face of the Lord in confession, with psalms and other works of charity.

Remember the destruction that was deservedly pronounced by prophetic utterance on those who, doing penance, were mercifully freed from the destruction threatened by the judgment of God …

from Henry Knighton, Chronicle (1378-96)

In that year and the following year there was a universal mortality of men throughout the world. It began first in India, then in Tarsus, then it reached the Saracens and finally the Christians and Jews. …

On a single day 1,312 people died in Avignon, according to a calculation made in the pope’s presence. On another day more than 400 died. 358 of the Do- minicans in Provence died during Lent. At Montpellier only seven friars survived out of 140. At Magdalen seven survived out of 160, which is quite enough. From 140 Minorites [i.e., Franciscans] at Marseilles not one remained to carry the news to the rest…. At the same time the plague raged in England. It began in the autumn in various places and after racing across the country it ended at the same time in the following year.

… Then the most lamentable plague penetrated the coast through Southampton and came to Bristol, and virtually the whole town was wiped out. It was as if sudden death had marked them down beforehand, for few lay sick for more than two or three days, or even for half a day. Cruel death took just two days to burst out all over a town. At Leicester, in the little parish of St. Leonard, more than 380 died; in the parish of Holy Cross more than 400; in the parish of St. Margaret 700; and a great multitude in every parish. The Bishop of Lincoln sent word through the whole diocese, giving general power to every priest (among the regular as well as the secular clergy) to hear confession and grant absolution with full and complete authority except only in cases of debt.1 In such cases the penitent, if it lay within his power, ought to make satisfaction while he lived, but certainly others should do it from his goods after his death. Similarly the Pope granted plenary remission of all sins to those at the point of death, the absolution to be for one time only, and the right to each person to choose his confessor as he wished.2 This concession was to last until the following Easter.

In the same year there was a great murrain3 of sheep throughout the realm, so much so that in one place more than 5,000 sheep died in a single pasture, and their bodies were so corrupt that no animal or bird would touch them. And because of the fear of death everything fetched a low price. For there were very few people who cared for riches, or indeed for anything else. A man could have a horse previously valued at 40s. for half a mark, a good fat ox for 4s., a cow for 12d., a bullock for 6d., a fat sheep for 4d., a ewe for 3d., a lamb for 2d., a large pig for 5d., a stone of wool for 9d. And sheep and cattle roamed unchecked through the fields and through the standing corn, and there was no one to chase them and round them up. For want of watching animals died in uncountable numbers in the fields and in bye-ways and hedges throughout the whole country; for there was so great a shortage of servants and laborers that there was no one who knew what needed to be done. There was no memory of so inexorable and fierce a mortality since the time of Vortigern, King of the Britons, in whose time, as Bede testifies in his De gestis Anglorum, there were not enough living to bury the dead. In the following autumn it was not possible to hire a reaper for less than 8d. and his food, or a mower for 12d. with his food.5 For which reason many crops rotted unharvested in the fields; but in the year of the pestilence, as mentioned above, there was so great an abundance of all types of grain that no one cared.

The Scots, hearing of the cruel plague of the English, declared that it had befallen them through the revenging hand of God, and they took to swearing “by the foul death of England”—or so the common report resounded in the ears of the English. And thus the Scots, believing that the English were overwhelmed by the terrible vengeance of God, gathered in the forest of Selkirk with the intention of invading the whole realm of England. The fierce mortality came upon them, and the sudden cruelty of a monstrous death winnowed the Scots. Within a short space of time around 5,000 died, and the rest, weak and strong alike, decided to retreat to their own country. But the English, following, surprised them and killed many of them. …

After the aforesaid pestilence many buildings of all sizes in every city fell into total ruin for want of inhabitants. Likewise, many villages and hamlets were deserted, with no house remaining in them, because everyone who had lived there was dead, and indeed many of these villages were never inhabited again. In the following winter there was such a lack of workers in all areas of activity that it was thought that there had hardly ever been such a shortage before; for a man’s farm animals and other livestock wandered about without a shepherd and all his possessions were left unguarded. And as a result all essentials were so expensive that something which had previously cost 1d. was now worth 4d. or 5d.

Confronted by this shortage of workers and the scarcity of goods the great men of the realm, and the lesser landowners who had tenants, remitted part of the rent so that their tenants did not leave. Some remitted half the rent, some more and some less; some remitted it for two years, some for three and some for one—whatever they could agree with their tenants. Likewise those whose tenants held by the year, by the performance of labor services (as is customary in the case of serfs), found that they had to release and remit such works, and either pardon rents completely or levy them on easier terms, otherwise houses would be irretrievably ruined and land left uncultivated. And all victuals and other necessities were extremely dear.

The Uprising of 1381 (The Peasants’ Revolt)

from Regulations, London (1350)

To amend and redress the damages and grievances which the good folks of the city, rich and poor, have suffered and received within the past year, by reason of masons, carpenters, plasterers, tilers, and all manner of laborers, who take immeasurably more than they have been wont to take, by assent of Walter Turk, mayor, the aldermen, and all the commonalty of the city, the points under-written are ordained, to be held and firmly observed for ever; that is to say:

In the first place, that the masons, between the Feasts of Easter and St. Michael, shall take no more by the working-day than 6d., without victuals or drink; and from the Feast of St. Michael to Easter, for the working- day, 5d. And upon Feast Days, when they do not work, they shall take nothing. And for the making or mending of their implements they shall take nothing.

Also, that the carpenters shall take, for the same time, in the same manner.

Also, that the plasterers shall take the same as the masons and carpenters take.

Also, that the tilers shall take for the working-day, from the Feast of Easter to St. Michael 5 1⁄2 d., and from the Feast of St. Michael 4 1⁄2 d.

Also, that the laborers shall take in the first half year 3 1⁄2 d., and in the other half 3d….

Also, that the tailors shall take for making a gown, garnished with fine cloth and silk, 18d.

Also, for a man’s gown, garnished with linen thread and with buckram, 14d.

Also, for a coat and hood, 10d.

Also, for a long gown for a woman, garnished with fine cloth or with silk, 2s. 6d.

Also, for a pair of sleeves, to change, 4d.

Also, that the porters of the city shall not take more for their labor than they used to take in olden time, on pain of imprisonment.

Also, that no vintner shall be so daring as to sell the gallon of wine of Vernaccia for more than 2s., and wine of Crete, wine of the River, Piement, and Clare, and Malveisin, at 16d. …

Also, that a pair of spurs shall be sold for 6d., and a better pair for 8d., and the best at 10d. or 12d., at the very highest.

Also, that a pair of gloves of sheepskin shall be sold for one penny, and a better pair at 1 1⁄2 d., and a pair at 2d., so going on to the very highest.

Also, that the shearmen shall not take more than they were wont to take; that is to say, for a short cloth 12d., and for a long cloth 2s.; and for a cloth of striped serge, for getting rid of the stripes, and shearing the same, 2s.

Also, that the farriers1 shall not take more than they were wont to take before the time of the pestilence, on pain of imprisonment and heavy ransom; that is to say, for a horse-shoe of six nails 11⁄2 d., and for a horse-shoe of eight nails 2d.; and for taking off a horse-shoe of six nails or of eight, one halfpenny; and for the shoe of a courser 2 1⁄2 d., and the shoe of a charger 3d.; and for taking off the shoe of a courser or charger, one penny.

Also, if any workman or laborer will not work or labor as is above ordained, let him be taken and kept in prison until he shall have found good surety, and have been sworn to do that which is so ordained. And if anyone shall absent himself, or go out of the city, because he does not wish to work and labor, as is before mentioned, and afterwards by chance be found within the city, let him have imprisonment for a quarter of the year, and forfeit his chattels which he has in the city, and then let him find surety, and make oath, as is before stated. And if he will not do this, let him forswear the city forever.

from Statute of Laborers (1351)

Because a great part of the people and especially of pestilence, some, seeing the needs of the masters and the scarcity of servants, are not willing to serve unless they receive excessive wages, and others, rather than gain their living through labor, prefer to beg in idleness. We, considering the grave inconveniences which might come from such a shortage, especially of ploughmen and such laborers, have held deliberation and discussion concerning this with the prelates and nobles and other learned men sitting by us, by whose consenting counsel we have seen fit to ordain that every man and woman of our kingdom of England, of whatever condition, whether serf or free, who is able bodied and below the age of 60 years, not living from trade or carrying on a definite craft, or having private means of living or private land to cultivate, and not serving another—if such a person is sought after to serve in a suitable service appropriate to that person’s status, that person shall be bound to serve whomever has seen fit so to offer such employment, and shall take only the wages, liveries, reward or salary usually given in that place in the twentieth year of our reign in England, or the usual year of the five or six preceding ones. This is provided so that in thus retaining their service, lords are preferred before others by their serfs or land tenants, so that such lords nevertheless thus retain as many as shall be necessary, but not more.

And if any man or woman, being thus sought after for service, will not do this, the fact being proven by two faithful men before the sheriffs or the bailiffs of our Lord the King, or the constables of the town where this happens to be done, immediately through them, or some one of them, that person shall be taken and sent to the next jail, and remain there in strict custody until offering security for serving in the aforesaid form. And if a reaper or mower, or other worker or servant, of whatever standing or condition, who is retained in the service of anyone, departs from the said service before the end of the agreed term without permission or reasonable cause, that person shall undergo the penalty of imprisonment, and let no one, under the same penalty, presume to receive or retain such a person for service. Let no one, moreover, pay or permit to be paid to anyone more wages, livery, reward or salary than was customary, as has been said.

… Likewise saddlers, skinners, tawyers, cord- wainers, tailors, smiths, carpenters, masons, tilers, shipwrights, carters and all other artisans and laborers shall not take for their labor and handiwork more than what, in the places where they happen to labor, was customarily paid to such persons in the said twentieth year and in the other usual years preceding, as has been said. And anyone who takes more shall be committed to the nearest jail in the aforesaid manner.

Likewise, let butchers, fishmongers, innkeepers, brewers, bakers, those dealing in foodstuffs and all other vendors of any victuals, be bound to sell such victuals for a reasonable price, having regard for the price at which such victuals are sold in the adjoining places, so that such vendors may have moderate gains, and not excessive ones, according as the distance of the places from which such victuals are carried may seem reasonably to require. And if anyone sells such victuals in another manner, and is convicted of it in the aforesaid way, that person shall pay double what was received to the injured party, or in default of the injured party, to another who shall be willing to prosecute in this behalf. …

And because many sturdy beggars refuse to labor so long as they can live from begging alms, giving themselves up to idleness and sin and, at times, to robbery and other crimes, let no one, under the aforesaid pain of imprisonment, presume, under color of piety or alms, to give anything to those who can very well work, or to cherish them in their sloth, so that thus they may be compelled to work for the necessities of life.

from Statute (1363)

… Item. Regarding the outrageous and excessive apparel of diverse people, violating their estate and degree, to the great destruction and impoverishment of the whole land, it is ordained that grooms (both servants of lords and those employed in crafts) shall be served meat or fish once a day, and the remaining occasions shall be served milk, butter, and cheese, and other such food, according to their estate. They shall have clothes for their wear worth no more than two marks, and they shall wear no cloth of higher price which they have bought themselves or gotten in some other way. Nor shall they wear anything of silver, embroidered items, nor items of silk, nor anything pertaining to those things. Their wives, daughters, and children shall be of the same condition in their clothing and apparel, and they shall wear no veils worth more than 12 pence a veil.

Item. Artisans and yeomen shall not take or wear cloth for their clothing or stockings of a higher price than 40 shillings for the whole cloth, by way of purchase or by any other means. Nor may they take or wear silk, silver, or jeweled cloth, nor shall they take or wear silver or gold belts, knives, clasps, rings, garters, or brooches, ribbons, chains, or any manner of silk apparel which is embroidered or decorated. And their wives, daughters and children are to be of the same condition in their dress and apparel. And they are to wear no veils made of silk, but only of yarn made within the kingdom, nor are they to wear any manner of fur or of budge, but only of lamb, rabbit, cat, or fox. …

Item. Knights who have land or rent valued up to 200 marks a year shall take and wear clothes of cloth valued at 6 marks for the whole cloth, and nothing of more expensive cloth. And they shall not wear cloth of gold or mantles or gowns furred with pure miniver or ermine, or any apparel embroidered with jewels or anything else. Their wives, daughters, and children will be of the same condition. And they shall not wear ermine facings or lettice or any jeweled apparel, except on their heads. All knights and ladies, however, who have land or rent of more than 400 marks a year, up to the sum of 1,000 marks, shall wear what they like, except ermine and lettice, and apparel with jewels and pearls, unless on their heads.

Item. Clergy who have any rank in a church, cathedral, college, or schools, or a cleric of the King who has an estate that requires fur, will wear and use it according to the constitution of the same. All other clergy who have 200 marks from land a year will wear and do as knights who receive the same rent. Other clergy with the same rent will wear what the esquires who have 100 pounds in rent wear. All of them, both clergy and knights, may wear fur in winter, and in the same manner will wear linure1 in summer.

Item. Carters, ploughmen, ploughdrivers, cowherds, shepherds, swineherds, and all other keepers of animals, wheat threshers and all manner of people of the estate of a groom occupied in husbandry, and all other people who do not have 40 shillings’ worth of goods or chattels will not take or wear any kind of cloth but blanket, and russet worth 12 pence, and shall wear belts of linen according to their estate. And domestic servants shall come to eat and drink in the manner pertaining to them, and not excessively. And it is ordained that if anyone wears or does contrary to the above, that person will forfeit to the King all the apparel thus worn against this ordinance.

Item. In order to maintain this ordinance and keep it in all points without exception, it is ordained that all makers of cloth within the realm, both men and women, shall confirm that they make their cloth according to the price set by this ordinance. And all the clothmakers shall buy and sell their varieties of cloth according to the same price, so that a great supply of such cloths will be made and put up for sale in every city, borough, and merchant town and elsewhere in the realm, so that no lack of supply of such cloths shall cause the violation of this ordinance. And to that end the said clothmakers will be constrained in any way that shall seem best to the King and his council. And this ordinance on new apparel shall take effect at the next Candlemas.

from Jean Froissart, Chronicle, Account of Sermon by John Ball (late 14th century)

There was a foolish priest in the county of Kent called John Ball, who, for his foolish words, had been three times in the Archbishop of Canterbury’s prison; for this priest used oftentimes, on the Sundays after Mass, when the people were going out of the minster, to go into the cloister and preach, and made the people to assemble about him, and would say thus, “Ah, ye good people, things are not going well in England, nor shall they do so till everything be common, and till there be no villeins nor gentlemen, but we be all united together, and the lords be no greater masters than we be. What have we deserved, or why should we be kept thus in serfdom? We be all come from one father and one mother, Adam and Eve; whereby can they say or show that they be greater lords than we be, except that they cause us to earn and labor for what they spend? They are clothed in velvet and camlet furred with gris, and we be vestured with poor cloth; they have their wines, spices, and good bread, and we have the drawing out of the chaff and drink water; they dwell in fair houses and we have the pain and travail, rain and wind in the fields; and by what cometh of our labors they keep and maintain their estates: we be called their bondmen, and unless we readily do them service, we be beaten; and we have no sovereign to whom we may complain, nor that will hear us and do us right. Let us go to the King—he is young—and show him what serfage we be in, and show him how we will have it otherwise, or else we will provide us with some remedy, either by fairness or otherwise.”

Thus John Ball said on Sundays, when the people issued out of the churches in the villages; wherefore many of the lowly people loved him, and said how he said truth; and so they would murmur one with another in the fields and in the ways as they went together, affirming how John Ball spoke the truth.

from Henry Knighton, Chronicle (1378–96)

In the year 1381, the second of the reign of King Richard II, during the month of May … that impious band began to assemble from Kent, from Surrey, and from many other surrounding places. Apprentices also, leaving their masters, rushed to join these. And so they gathered on Blackheath, where, forgetting themselves in their multitude, and neither contented with their former cause nor appeased by smaller crimes, they unmercifully planned greater and worse evils and determined not to desist from their wicked undertaking until they should have entirely extirpated the nobles and great men of the kingdom.

So at first they directed their course of iniquity to a certain town of the Archbishop of Canterbury called Maidstone, in which there was a jail of the said Arch- bishop, and in the said jail was a certain John Ball, a chaplain who was considered among the laity to be a very famous preacher; many times in the past he had foolishly spread abroad the word of God, by mixing tares with wheat, too pleasing to the laity and extremely dangerous to the liberty of ecclesiastical law and order, execrably introducing into the Church of Christ many errors among the clergy and laymen. For this reason he had been tried as a clerk and convicted in accordance with the law, being seized and assigned to this same jail for his permanent abiding place. On [June 12,] the Wednesday before the Feast of the Consecration, they came into Surrey to the jail of the King at Marshalsea, where they broke the jail without delay, forcing all imprisoned there to come with them to help them; and whomsoever they met, whether pilgrims or others of whatever condition, they forced to go with them.

On [June 14,] the Friday following the Feast of the Consecration, they came over the bridge to London; here no one resisted them, although, as was said, the citizens of London knew of their advance a long time before; and so they directed their way to the Tower where the King was surrounded by a great throng of knights, esquires, and others. It was said that there were in the Tower about one hundred and fifty knights together with one hundred and eighty others….

John Leg and a certain John, a Minorite, a man active in warlike deeds, skilled in natural sciences, an intimate friend of Lord John, duke of Lancaster, hastened with three others to the Tower for refuge, intending to hide themselves under the wings of the King. The people had determined to kill the Archbishop and the others above mentioned with him; for this reason they came to this place, and afterwards they fulfilled their vows. The King, however, desired to free the Archbishop and his friends from the jaws of the wolves, so he sent to the people a command to assemble outside the city, at a place called Mile End, in order to speak with the King and to treat with him concerning their designs. The soldiers who were to go forward, consumed with folly, lost heart, and gave up, on the way, their boldness of purpose. Nor did they dare to advance but, unfortunately, struck as they were by fear, like women, kept themselves within the Tower.

But the King advanced to the assigned place, while many of the wicked mob kept following him. … More, however, remained where they were. When the others had come to the King they complained that they had been seriously oppressed by many hardships and that their condition of servitude was unbearable, and that they neither could nor would endure it longer. The King, for the sake of peace, and on account of the violence of the times, yielding to their petition, granted to them a charter with the great seal, to the effect that all men in the kingdom of England should be free and of free condition, and should remain both for themselves and their heirs free from all kinds of servitude and villeinage forever. This charter was rejected and decided to be null and void by the King and the great men of the kingdom in the Parliament held at Westminster in the same year, after the Feast of St. Michael.

While these things were going on, behold those degenerate sons, who still remained, summoned their father the Archbishop with his above-mentioned friends without any force or attack, without sword or arrow, or any other form of compulsion, but only with force of threats and excited outcries, inviting those men to death. But they did not cry out against it for themselves, nor resist, but, as sheep before the shearers, going forth barefooted with uncovered heads, ungirt, they offered themselves freely to an undeserved death, just as if they had deserved this punishment for some murder or theft. And so, alas! before the King returned, seven were killed at Tower Hill, two of them lights of the kingdom, the worthy with the unworthy. John Leg and his three associates were the cause of this irreparable loss. Their heads were fastened on spears and sticks in order that they might be told from the rest. …

Whatever representatives of the law they found or whatever men served the kingdom in a judicial capacity, these they slew without delay.

On the following day, which was Saturday, they gathered in Smithfield, where there came to them in the morning the King, who although only a youth in years yet was in wisdom already well versed. Their leader, whose real name was Wat Tyler, approached him; already they were calling him by the other name of Jack Straw. He kept close to the King, addressing him for the rest. He carried in his hand an unsheathed weapon which they call a dagger, and, as if in childish play, kept tossing it from one hand to the other in order that he might seize the opportunity, if the King should refuse his requests, to strike the King suddenly (as was commonly believed); and from this thing the greatest fear arose among those about the King as to what might be the outcome.

They begged from the King that all the warrens, well waters, park, and wood, should be common to all, so that a poor man as well as a rich should be able freely to hunt animals everywhere in the kingdom—in the streams, in the fish ponds, in the woods, and in the forest; and that he might be free to chase the hare in the fields, and that he might do these things and others like them without objection. When the King hesitated about granting this concession Jack Straw came nearer, and, speaking threatening words, seized with his hand the bridle of the horse of the King very daringly. When John de Walworth, a citizen of London, saw this, thinking that death threatened the King, he seized a sword and pierced Jack Straw in the neck. Seeing this, another soldier, by name Radulf Standyche, pierced his side with another sword. He sank back, slowly letting go with his hands and feet, and then died. A great cry and much mourning arose: “Our leader is slain.” When this dead man had been meanly dragged along by the hands and feet into the church of St. Bartholomew, which was near by, many withdrew from the band, and, vanishing, betook themselves to flight, to the number it is believed of ten thousand. …

After these things had happened and quiet had been restored, the time came when the King caused the offenderstobepunished.SoLordRobertTresillian,one of the judges, was sent by order of the King to inquire into the uprisings against the peace and to punish the guilty. Wherever he came he spared no one, but caused great slaughter. …

For whoever was accused before him in this said cause, whether justly or as a matter of spite, he immediately passed upon him the sentence of death. He ordered some to be beheaded, others to be hanged, still others to be dragged through the city and hanged in four different parts thereof; others to be disemboweled, and the entrails to be burned before them while they were still alive, and afterwards to be decapitated, quartered, and hanged in four parts of the city according to the greatness of the crime and its desert. John Ball was captured at Coventry and led to St. Albans, where, by order of the King, he was drawn and hanged, then quartered, and his quarters sent to four different places.

Source Texts:

Douglas, David Charles and Harry Rothwell. “From the Life of Edward II.” English Historical Documents: 1189-1327, Psychology Press, 1996. is included under fair use for educational purposes only. All rights reserved.

Froissart, Jean. Chronicles of England, France, Spain. H.G. Bonn, 1857, is licensed under no known copyright.

Lumby, J.R., ed. “From: Henry Knighton’s Chronicles.” Chronicron Henrici Knighton vel Cnitthon monachi Leycestrensis, Rolls Series, 1889-95, is licensed under no known copyright.

Riley, Henry Thomas, ed. “Regulations, London (1350)” and “Letter to the People of London (1356).” Memorials of London and London Life in the XIIIth, IVth, and IVth Centuries. Longmans, 1868, is licensed under no known copyright.

White, Albert Beebe and Wallace Notestein, eds. “Statute of Laborers (1351).” Source Problems in English History. Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1915, is licensed under no known copyright.

Winbolt, S.E., et. al, eds. “Statute (1363).” War and Misrule: English History Source Books, G. Bell and Sons, 1913, is licensed under no known copyright.

Wilkins, David. “Ralph of Shrewsbury, Letter (17 August 1348).” Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, a synodo verolamiensi A.D. CCCC XLVI ad londinensem A.D. M DCCXVII. , 1737, is licensed under no known copyright.