50 Roger Ascham: From The Schoolmaster

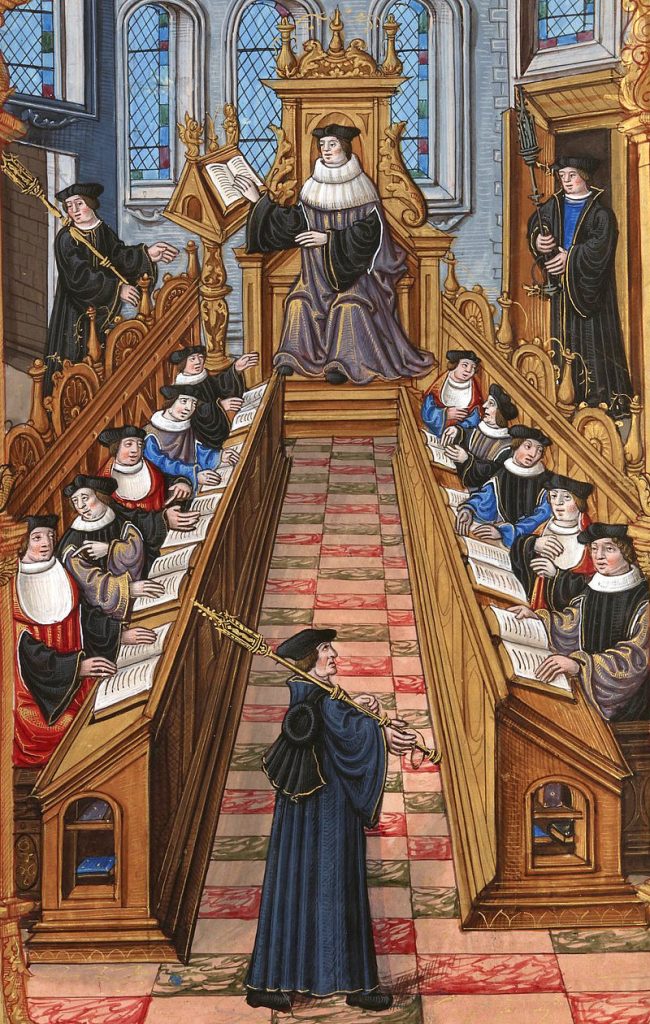

“Illustration from a 14th-century manuscript showing a meeting of doctors at the University of Paris, “by unknown artist, c. 1537. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

by Marcus Litz

The Merchant Taylors’ School, founded in 1561, was one of several new English grammar schools opened in the 1500s. Before the reign of Henry VIII (1491–1547), the primary centers of education in England had been monasteries, where monks and priests had spent their lives in prayer and study. These monasteries established and ran schools that educated the sons of the wealthy. But after Henry broke with the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s, he instituted a number of reforms, including the dissolution of the monasteries and went about confiscating all church property. With the monastery schools thus closed, Henry founded several new grammar schools, including the King’s School in Canterbury that Marlowe attended (“The Schoolmaster”). Henry’s heir, Edward VI, chartered many more schools. In addition, charitable organizations supported education by opening new schools and sponsoring scholarships. The Merchant Taylors’ School, for example, was created and supported by an organization of businessmen, the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors (“The Schoolmaster)”.

With more people gaining access to education, debates arose regarding curriculum and methods of teaching. Though strict instruction and beatings were the norm, a few influential educators began to argue in favor of a more lenient approach that, they believed, would inspire their students to love learning. Richard Mulcaster for example, the first headmaster of the Merchant Taylors’ School, developed an educational philosophy that acknowledged children’s different abilities, emphasized the importance of exercise and sports, recommended greater respect for the English Language, and supported the education of girls (Engel).

Very few children in sixteenth-century England attended formal school, but interest in education was growing. Literacy was an important skill for merchants and businessmen, and it was also the mark of a gentleman. Wealthy families, therefore, expected their children to study at school or with a private tutor. Middle-class families, too, were increasingly interested in obtaining basic education for their children. In 1563 Ascham began his work The Schoolmaster, published posthumously in 1570, which ensured his later reputation as a pioneer in the field of pedagogy. Richard Sackville, as he states in the book’s preface, told Ascham that “a fond schoolmaster” had made him hate learning and as he had now a young son, whom he wished to be learned, he offered, if Ascham would name a tutor, to pay for the education of their respective sons under Ascham’s orders, and invited Ascham to write a treatise on “the right order of teaching” (Roger). The Schoolmaster was the result.

The memory arts in Renaissance England not only shape curricular matters such as the humanist project of reviving the classical past and its wisdom through learning Greek and Latin but also influenced the psychology of pedagogy – the examination of the scholar’s wits most famously explored by Juan Huarte in 1575 (Engel). Ascham argues that schoolmasters do not know how to identify the best minds among students. They favour quick wits instead of hard ones, failing to realise that quick wits are quick to forget, while hard wits, like inscriptions made in stone, which require effort, retain things the longest. Ascham’s logic operates according to the fundamental Aristotelian distinction between the “hard” and “soft” mind. The excerpt conforms to similar reasoning in observing that the youthful mind is impressionable like the newest wax, another classical trope for memory storage. As a result, young students are most receptive to the love of learning and do not need to be beaten to retain their lessons, especially as such trauma may induce forgetfulness.

Works Cited

Engel, William E., et al., editors. “Roger Ascham, The Schoolmaster (1570).” The Memory Arts in Renaissance England: A Critical Anthology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016, pp. 153–155

“Roger Ascham.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 May 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Ascham#The_School_master.

“The Schoolmaster.” Elizabethan World Reference Library, Encyclopedia.com, 2019, www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/schoolmaster.

Discussion Questions

- Knowing that perseverance or grit is needed to succeed, how does one teach that?

- What ideas of Ascham’s do you recognize from your own experiences in school? What seems antiquated?

- In what ways was Ascham responsible for shaping the course of English history?

- What can an individual do or lean on their own versus what do they need to be taught? How do they need to be taught?

- Why did Roger Ascham split the story into two sections each covering a different point of view and differing ideologies?

Further Resources

Reading: From The Schoolmaster

TEACHING LATIN

There is a way touched in the first book of Cicero de Oratore, which, wisely brought into scholes, truly taught, and constantly used, would not only take wholly away this butcherly fear in making of Latines, but would also with ease and pleasure, and in short time, as I know by good experience, work a true choice and placing of words, a right ordering of sentences, an easy understanding of the tongue, a readiness to speak, a facility to write, a true judgment both of his own and other men’s doings, what tongue soever he doth use. ”

The way is this : after the three concordances learned, as I touched before, let the master read unto him the Epistles of Cicero, gathered together, and chosen out by Sturmius, for the capacity of children. ”

First, let him teach the child chearfully and plainly the cause and matter of the letter ; then, let him construe k into English, so oft as the child may easily carry away the understanding of it ; lastly, parse it over perfectly. This done thus, let the child, by and by, both construe and parse it over again ; so that it may appear, that the child doubteth in nothing that his master taught him before. After this, the child must take a paper book, and sitting in some place, where no man shall prompt him, by himself) let him translate into English his former lesson. Then shewing it to his master, let the master take from him his Latin book, and pausing an hour at the least, then let the child translate his own English into Latin again in another paper book. When the child bringeth it turned into Latin, the master must compare it with Tully’s book, and lay them both together ; and where the child doth well, either in chusing, or true placing Tully’s words, let the master praise him, and say, Here you do well. For, I assure you, there is no such whetstone to sharpen a good wit, and encourage a will to learning, as is praise.

But if the child miss, either in forgetting a word, or in changing a good with a worse, or misordering the sentence, I would not have the master either frown, or chide with him, if the child hath done his diligence and used no truantship therein; for I know by good experience, that a child shall take more profit of two faults gently warned of than of four things rightly hit; for then the master shall have good occasion to say unto him,

‘Tully would have used such a word, not this; Tully would have placed this word here, not there: would have used this case, this number, this person, this degree, this gender; he would have used this mood, this tense, this simple rather than this compound; this adverb here, not there; he would have ended the sentence with this verb, not with that noun or participle,’ &c.

In these few lines, I have wrapped up the most tedious part of grammar, and also the ground of almost all the rules that are so busily taught by the master, and so hardly learned by the scholar in all common scholes ; which after this sort the master shall teach without all error, and the scholar shall learn without great pain ; the master being led by so sure a guide, and the scholar being brought into so plain and easy a way. This is a lively and perfect way of teaching of rules ; where the common way used in common scholes, to read the grammar alone by itself, is tedious for the master, hard for the scholar, cold and uncomfortable for them both.

Let your scholar be never afraid to ask you any doubt, but use discreetly the best allurements ye can to encourage him to the same, lest his overmuch fearing of you drive him to seek some misorderly shift, as to seek to be helped by some other book, or to be prompted by some other scholar, and so go about to beguile you much, and himself more.

The Italianate Englishman

…But I am afraid that over-many of our travellers into Italy do not eschew the way to Circe’s Court, but go and ride, and run, and fly thither; they make great haste to come to her ; they make great suit to serve her ; yea, I could point out some with my finger that never had gone out of England but only to serve Circe in Italy. Yanity and vice and any licence to ill living in England was counted stale and rude unto them. And so, being mules and horses before they went, returned very swine and asses home again ; yet everywhere very foxes with subtle and busy heads; and where they may, very wolves with cruel malicious hearts. A marvellous monster, which for filthiness of living, for dulness of learning himself, for wiliness in dealing with others, for malice in hurting without cause, should carry at once in one body the belly of a swine, the head of an ass, the brain of a fox, the womb of a wolf. If you think we judge amiss and write too sore against you, hear what the Italian saith of the Englishman, what the master reporteth of the scholar; who uttereth plainly what is taught by him and what is learned by you, saying, ” Inglese Italianato e un didbolo inoarnato,” that is to say, you remain men in shape and fashion, but become devils in life and condition. This is not the opinion of one for some private spite, but the judgment of all in a common proverb, which riseth of that learning and those manners which you gather in Italy: a good schoolhouse of household doctrine, and worthy masters of commendable scholars, where the master had rather defame himself for his teaching, than not shame his scholar for his learning. A good nature of the master, and fair conditions of the scholars. And now choose you, you Italian Englishmen, whether you will be angry with us for calling you monsters, or with the Italians for calling you devils, or else with your own selves that take so much pains and go so far to make yourselves both. If some yet do not well understand what is an Englishman Italianated, I will plainly tell him. He that by living and travelling in Italy bringeth home into England out of Italy the religion, the learning, the policy, the experience, the manners of Italy. That is to say, for religion, Papistry or worse; for learning, less commonly than they carried out with them; for policy, a factious heart, a discoursing head, a mind to meddle in all men’s matters; for experience, plenty of new mischiefs never known in England before; for manners, variety of vanities and change of filthy living. These be the enchantments of Circe, brought out of Italy to mar men’s manners in England; much by example of ill life, but more by precepts of fond books of late translated out of Italian into English, sold in every shop in London, commended by honest titles the sooner to corrupt honest manners; dedicated over-boldly to virtuous and honourable personages, the easier to beguile simple and innocent wits. It is pity that those which have authority and charge to allow and disallow books to be printed, be no more circumspect herein than they are. Ten sermons at Paul’s Cross do not so much good for moving men to true doctrine as one of those books do harm with enticing men to ill living. Yea, I say farther, those books tend not so much to corrupt honest living as they do to subvert true religion. More Papists be made by your merry books of Italy than by your earnest books of Lovaine. And because our great physicians do wink at the matter, and make no count of this sore, I, though not admitted one of their fellowship, yet having been many years a prentice to God’s true religion, and trust to continue a poor journeyman therein all days of my life, for the duty I owe and the love I bear both to true doctrine and honest living, though I have no authority to amend the sore myself, yet I will declare my goodwill to discover the sore to others.

St. Paul saith that sects and ill opinions be the works of the flesh and fruits of sin. This is spoken no more truly for the doctrine than sensible for the reason. And why? For ill doings breed ill thinkings. And of corrupted manners spring perverted judgments. And how? There be in man two special tilings : man’s will, man’s mind. Where will inclineth to goodness, the mind is bent to truth. Where will is carried from goodness to vanity, the mind is soon drawn from truth to false opinion. And so the readiest way to entangle the mind with false doctrine is first to entice the will to wanton living. Therefore when the busy and open Papists abroad could not by their contentious books turn men in England fast enough from truth and right judgment in doctrine, then the subtle and secret Papists at home procured bawdy books to be translated out of the Italian tongue, whereby over-many young wills and wits allured to wantonness do now boldly contemn all severe books that sound to honesty and godliness. In our forefathers’ time* when Papistry, as a standing pool, covered and overflowed all England few books were read in our tongue, saving certain books of chivalry, as they said, for pastime and pleasure, which, as some were made in monasteries by idle monks or wanton canons: as one, for example, ” Morte Arthur,” the whole pleasure of which book standeth in two special points in open manslaughter and bold bawdry. In which book those be counted the noblest knights that do kill most men without any quarrel, and commit foulest adulteries by subtlest shifts : as Sir Launcelot with the wife of King Arthur, his master ; Sir Tristram with the wife of King Mark, his uncle; Sir Lamerock with the wife of King Lote, that was his own aunt. This is good stuff for wise men to laugh at or honest men to take pleasure at! Yet I know when God’s Bible was banished the Court, and ” Morte Arthur ” received into the prince’s chamber.

Source Text:

Ascham, Roger. The Schoolmaster, John Daye, 1570, is licensed under no known copyright.