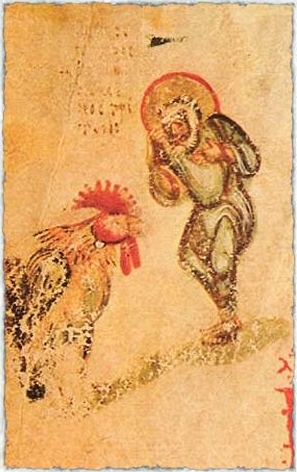

44 Robert Henryson: The Cock and the Jasp

|

Introduction

by Xondria Lloyd

“The Taill of the Cok and the Jasp” is a Middle Scots version of Aesop’s Fable The Cock and the Jewel by the 15th-century Scottish poet Robert Henryson. It is the first in Henryson’s collection known as the Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian. The Cok and the Jasp is framed by a prologue and a moralitas, and as the first poem in the collection it operates on a number of levels, and in all its parts, to introduce the larger cycle.

Biography

Much of Robert Henryson’s life is unknown. He was studying at Glasgow University in 1462, and he appears to have graduated after receiving training in the law. A 1571 edition of Henryson’s work noted that he was a schoolmaster at the Benedictine Abbey school in the town of Dunfermline, a school that had a reputation as being one of the most respected and wealthy in all of Scotland. It is clear Henryson lived a privileged life and likely worked in a position that gave him significant status in society (“Robert Henryson: Poet”).

Literary Context

His poem, the Cock and the Jasp, appears in his collection of poems that is known as The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian, and this work is a set of philosophical fables about animals who face various human-like ethical dilemmas. The fables were probably written in the 1460s and are heavily inspired by Aesop’s fables about beasts. This particular poem is a re-telling of Aesop’s tale that is known as The Cock and the Jewel (“Robert Henryson: Poet”).

Henryson crafted this poem in the style of “rime royal,” which is a form of rhyming poetry written in seven-line stanzas. This style of poetry was made famous in English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer during the 14th century (“Rime Royal”). Henryson has also been described in academic texts as a “Makar” or a “Scottish Chaucerian,” which means that he was a Scottish poet who wrote in the style of Chaucer (“Makar”).

At the end of his poem, after the Cock had left to find more food, Henryson further writes a message that is written in a style known as moralitas, and the message is intended to explain the meaning and importance of the fable. Moralitas is a moral message that was frequently used in fables written during this period (“The Thirteen Moral Fables of Robert Henryson”).

Historical Context

Henryson was probably considered to be a high-status man in his society, and his poetry has been regarded as masterful because he interweaves commonplace elements of Scottish culture into his work. In The Cock and the Jasp, some examples of these shared cultural elements are the “midden,” or refuse pile, and the Cock, as well as his predilection for grain (“The Thirteen Moral Fables”). Many Scottish people in the 15th century should have had middens where they lived or nearby their homes. They also would have had experience or firsthand knowledge of keeping chickens as domestic livestock (Slavin). These details and imagery in Henryson’s writing would have been well-known to the readers of his time, and they help to place his characters into a time and place that has been described as characteristic of Scotland in the late Middle Ages (“Robert Henryson: Poet”).

Summary

The Cock and the Jasp, written by Robert Henryson, is a poem about a rooster who, while digging in a trash heap for his meal, uncovers a gem. Though the fowl remarks on the gem’s beauty and definite value, he declares that it has no value for him, and he leaves the jewel on the ground to continue looking for grain.

Works Cited

“Makar.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 17 Nov. 2016, www.britannica.com/art/makar. Accessed 03 May 2020.

“Rime Royal.” The Geoffrey Chaucer Page, 12 June 2000, sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/litsubs/style/rime-roy.html. Accessed 03 May 2020.

“Robert Henryson: Poet.” Scottish Poetry Library, n.d. www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poet/robert-henryson/. Accessed 03 May 2020.

Slavin, Philip. “Chicken Husbandry in Late-Medieval Eastern England: c. 1250–1400.” Anthropozoologica, 44 (2): 2009. sciencepress.mnhn.fr/sites/default/files/articles/pdf/az2009n2a2.pdf. Accessed 03 May 2020.

“The Thirteen Moral Fables of Robert Henryson – The Cock & the Jasp.” Robert Henryson Page, n.d. www.arts.gla.ac.uk/STELLA/STARN/poetry/HENRYSON/fables/jasp.htm. Accessed 03 May 2020.

Discussion Questions

- What is the symbolism of the rooster and the jasp?

- What are the implications of the Cock and the “flighty lasses, nothing in their head” overlooking the lost gem?

- What are the connotations of the jewel’s “seven fair properties”?

- Could the Cock have any uses for the jasp, or is he correct that the gem is of “nae use” to him?

- What is the narrator’s goal in asking the reader to “go seek the Jasp” at the end of the story?

Further Resources

- An informational page about “The Cock and the Jasp” on a website dedicated to Robert Henryson’s moral fables.

- A video (0:53) illustration, The Rooster and the Jewel, based on Aesop’s fable.

- A modern-verse translation of Aesop’s fable called the “The Cock & the Jewel” contained in the Æsop for Children and presented by the Library of Congress.

Reading: The Cock and the Jasp

| 1. | A cockerel once, his plumage fresh and gay, Happy enough, although he was gey puir, Flew to the midden early-on one day; To get his stomach filled was all his care. Scraping in ashes, he by chance laid bare A Jasp. Gey little care was kept It seems, in one house, when the floor was swept. |

| 2. | These flighty lasses, nothing in their head Except to play, and on the street be seen; In tidying the house they take no heed To what’s swept up, as long’s the floor looks clean; Jewels are dropped, as often has been seen, Upon the floor, and swept up right away, And that’s what happened here, one well might say. |

| 3. | So, gazing on this find, quoth he, ” O ye rare gem, ye rich and noble thing! Though I’m your finder, ye’re nae use to me; By richts, ye should adorn some lord or king. This is case for sadness and mourning To see ye buried here in muck and mould When ye’re so braw, and worth so muckle gold. |

| 4. | Pity it’s me that’s found ye, and for why? Your virtues great, as weel’s your colours clear Are past my powers to praise or magnify, And mair than that; to me ye gi’e sma’ cheer. For, though to princes ye are sweet and dear, Dearer to me are things o’ much less cop, Like draff or crusts to fill my empty crop. |

| 5. | I would much raither scrape here wi’ my nails Among this dirt, and find my proper food, Like tailings corn, wee worms, or muckle snails, And siclike meat to do my stomach good Than find o’ jewels a michty multitude; By the same token, ye could, in your turn, As worthless rubbish, all my diet spurn. |

| 6. | Ye have nae corn, and corn is what I need; Your colours just gi’e comfort to the sicht, And sight itself will not my stomach feed; The saying is, that looking wark is licht! Meat must I have, obtain it as I micht, For hungry bodies cannae live on looks; Gi’e me dry bread, and ye can keep your cooks. |

| 7. | And where, by richts, should ye be settled down? Where should ye bide, but in a royal tower? Where should ye shine, but in a great king’s crown, Admired and praised, the emblem o’ great power? Rise, noble gem, o’ every jewel the flower, Out of this bog, and pass where ye should be; Ye are nae use to me, or me to ye.” |

| 8. | Leaving this jewel lying on the ground, This Cock, to seek his food, his own ways went; But by whom, when, and how this gem was found, Concerns not at all this argument, For it’s the deeper meaning and intent Which Aesop had when he composed this Fable That I’ll explain – as far as I am able. |

| 9. | For seven fair properties do in this jewel lie: The first, of colour it is marvellous; Whiles red as fire, whiles bright blue as the sky; It strengthens man, and renders him victorious; Keeping him safe from all things that are perilous. Who has this stone can look to prosper fair; Of bodily danger he need not beware. |

| 10. | This noble gem, so wonderful of hue, Perfect prudence and wisdom signifies; Many’s the story of its great virtue; Above all worldly things it aye shall rise, Leading all men their honour first to prize, Certain and sure to have the victory O’er fleshly vice and spiritual enemy. |

| 11. | Who can be prosperous, who can win renown, Who can steer safely through a stormy sea, Who can control a kingdom, house, or town, Devoid of learning? None, we all agree. Learning endures in perpetuity; Mildew or moth or rust have no effect Upon the treasures of the intellect. |

| 12. | This Cock, desiring nothing more than corn, May to that fool be easily compared Who at all learning makes a mock and scorn, Decrying it; of truth he is affeared, Turning away when discourse can be heard, As would a hungry sow, when, just for once, Instead of slops, she’s offered precious stones. |

| 13. | Those who dismiss our learning can be seen As sticks or clods, refusing to be taught About those treasures, great and evergreen, Which never can with worldly wealth be bought. That man does well, who all his days has sought Above all else, his knowledge to increase; He needs no more, to live and die in peace. |

| 14. | But nowadays, this gem in dross is buried; Little it’s missed, not do men seem to mind; Some gold they get, and then they are not worried About their learning, for their souls are blind. Well, on this theme, I might be wasting wind, And so I’ll stop. I’ll say nae mair, Except : go seek the Jasp -for it’s still there! |

Source Text:

Henryson, Robert. Thirteen Moral Fables of Robert Henryson, University of Glasgow, 1999, is licensed under no known copyright.