51 Thomas Wyatt, the Elder: Selected Poems

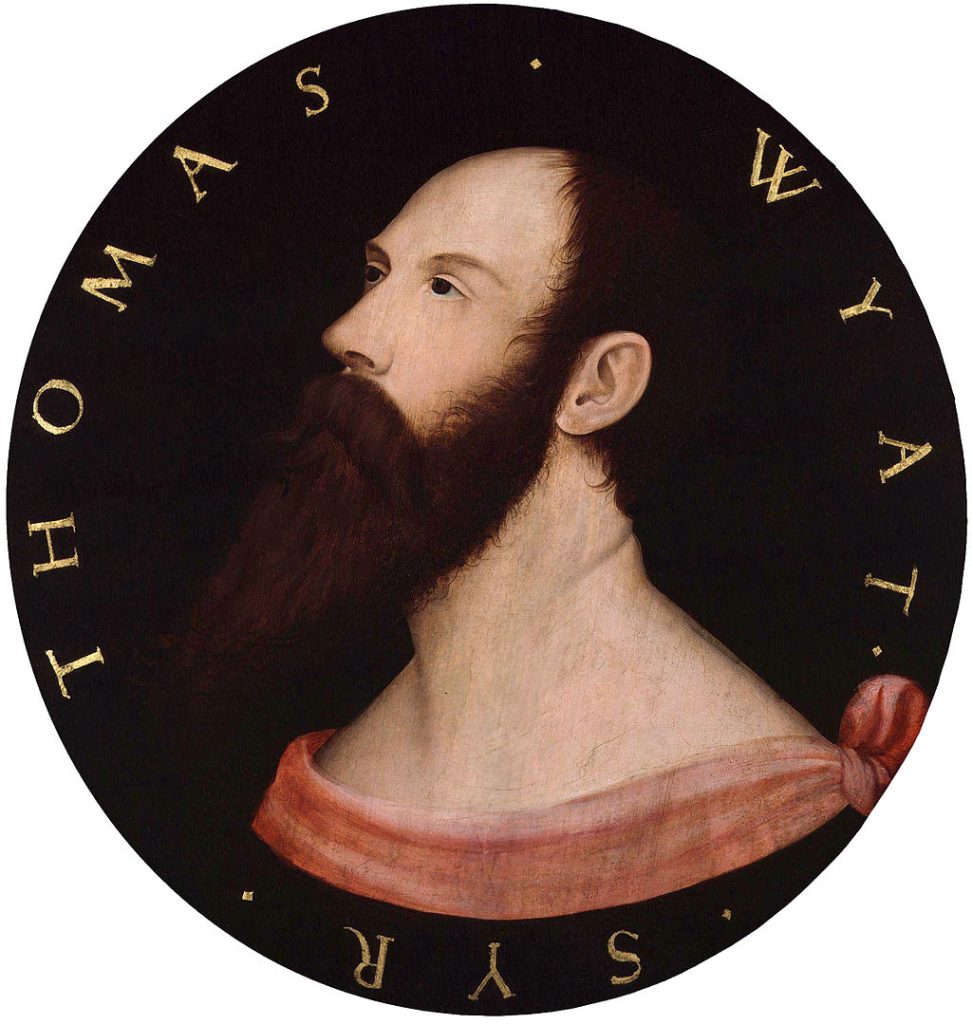

“Portrait of Sir Thomas Wyatt,” derived from a lost drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1540. Wikimedia Commons.

Introduction

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 1542) was a 16th-century English politician, ambassador, and lyric poet credited with introducing the sonnet to English literature. His professed object was to experiment with the English language, to civilise it, to raise its powers to equal those of other European languages. A significant amount of his literary output consists of translations and imitations of sonnets by Italian poet Petrarch; he also wrote sonnets of his own.

Biography

He was born at Allington Castle near Maidstone in Kent, though the family was originally from Yorkshire. His family adopted the Lancastrian side in the Wars of Roses. His mother was Anne Skinner, and his father Henry had been a Privy Councillor of Henry VII and remained a trusted adviser when Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509. Thomas followed his father to court after his education at St John’s College, Cambridge. Entering the King’s service, he was entrusted with many important diplomatic missions. In public life his principal patron was Thomas Cromwell, after whose death he was recalled from abroad and imprisoned (1541). Though subsequently acquitted and released, shortly thereafter he died. His poems were circulated at court and may have been published anonymously in the anthology The Court of Venus (earliest edition c.1537) during his lifetime, but were not published under his name until after his death; the first major book to feature and attribute his verse was Tottel’s Miscellany (1557), printed 15 years after his death.

Literary Context

Wyatt’s poetry reflects classical and Italian models, but he also admired the work of Geoffrey Chaucer, and his vocabulary reflects that of Chaucer; for example, he uses Chaucer’s word newfangleness, meaning fickle, in They flee from me that sometime did me seek. Many of his poems deal with the trials of romantic love, and the devotion of the suitor to an unavailable or cruel mistress.[18] Other poems are scathing, satirical indictments of the hypocrisies and pandering required of courtiers who are ambitious to advance at the Tudor court.

Works Cited

“Thomas Wyatt.” Wikipedia. 02 August 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wyatt_(poet) Accessed 30 Sept. 2020.

Discussion Questions

- Many of Wyatt’s poems are thought to be a commentary on the intrigue of Tudor court. What might be some examples from the poems below?

- “Whoso List to Hunt” is believed, by literary scholars and historians, to be about Anne Boleyn. How might we know this? What clues are there?

- Wyatt’s poems were published 15 years after his death when his expressive metrical form was considered outdated; what had replaced it? And how does the form sound to modern ears?

- A key theme here is love. How does Wyatt regard it? Are there shifts and changes among the selections?

- Are there any images, metaphors or motifs that repeat among the poems?

Further Resources

Reading: Selected Poems

The Long Love that in my thought doth Harbor

Whoso List to Hunt

hind!

But as for me, alas! I may no more,

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore ;

I am of them that furthest come behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow; I leave off therefore,

Since in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt

As well as I, may spend his time in vain !

And graven with diamonds in letters plain,

There is written her fair neck round about ;

‘ Noli me tangere; for Cæsar’s I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.’

Farewell, Love

ever ;

Thy baited hooks shall tangle me no more.

Senec, and Plato, call me from thy lore,

To perfect wealth, my wit for to endeavour;

In blind error when I did persevere,

Thy sharp repulse, that pricketh aye so sore,

Taught me in trifles that I set no store ;

But scaped forth thence, since, liberty is lever1

Therefore, farewell! go trouble younger hearts,

And in me claim no more authority :

With idle youth go use thy property,2

And thereon spend thy many brittle darts :

For, hitherto though I have lost my time,

Me list no longer rotten boughs to clime.

I Find no Peace

I fear and hope, I burn, and freeze like

ice ;

I fly aloft, yet can I not arise ;

And nought I have, and all the world I seize on,

That locks nor loseth, holdeth me in prison,

And holds me not, yet can I scape no wise :

Nor lets me live, nor die, at my devise,

And yet of death it giveth me occasion.

Without eye I see ; without tongue I plain :

I wish to perish, yet I ask for health ;

I love another, and thus I hate myself ;

I feed me in sorrow, and laugh in all my pain.

Lo, thus displeaseth me both death and life,

And my delight is causer of this strife.

My Galley

My galley chargèd with forgetfulness

Thorough2 sharp seas, in winter nights doth pass

‘Tween rock and rock; and eke mine enemy, alas,

That is my lord, steereth with cruelness,

And every oar a thought in readiness,

As though that death were light in such a case.

An endless wind doth tear the sail apace

Of forcèd sighs and trusty fearfulness.

A rain of tears, a cloud of dark disdain,

Hath done the wearied cords great hinderance;

Wreathèd with error and eke with ignorance.

The stars be hid that led me to this pain.

Drownèd is reason that should me consort,

And I remain despairing of the port.

Divers doth Use

Divers doth use, as I have heard and know,

When that to change their ladies do begin,

To mourn and wail, and never for to lynn,1

Hoping thereby to ‘pease their painful woe.

And some there be that when it chanceth so

That women change, and hate where love hath been,

They call them false, and think with words to win

The hearts of them which otherwhere doth grow.

But as for me, though that by chance indeed

Change hath outworn the favour that I had,

I will not wail, lament, nor yet be sad,

Nor call her false that falsely did me feed ;

But let it pass, and think it is of kind

That often change doth please a woman’s mind.

What Vaileth Truth?

What ‘vaileth truth, or by it to take pain ?

To strive by steadfastness for to attain

How to be just, and flee from doubleness ?

Since all alike, where ruleth craftiness,

Rewarded is both crafty, false, and plain.

Soonest he speeds that most can lie and feign :

True meaning heart is had in high disdain.

Against deceit and cloaked doubleness,

What ‘vaileth truth, or perfect steadfastness ?

Deceived is he by false and crafty train,

That means no guile, and faithful doth remain

Within the trap, without help or redress :

But for to love, lo, such a stern mistress,

Where cruelty dwells, alas, it were in vain.

What ‘vaileth truth !

Madam, withouten Many Words

Madam, withouten many words,

Once I am sure you will, or no :

And if you will, then leave your

bourds,

And use your wit, and shew it so,

For, with a beck you shall me call ;

And if of one, that burns alway,

Ye have pity or ruth at all,

Answer him fair, with yea or nay.

If it be yea, I shall be fain ;

If it be nay—friends, as before ;

You shall another man obtain,

And I mine own, and yours no more.

They Flee from Me

They flee from me, that sometime did me

seek,

With naked foot stalking within my

chamber :

Once have I seen them gentle, tame, and meek,

That now are wild, and do not once remember,

That sometime they have put themselves in danger

To take bread at my hand; and now they range

Busily seeking in continual change.

Thanked be Fortune, it hath been otherwise

Twenty times better; but once especial,

In thin array, after a pleasant guise,

When her loose gown did from her shoulders fall,

And she me caught in her arms long and small,

And therewithal sweetly did me kiss,

And softly said, ‘ Dear heart, how like you this ?’

It was no dream ; for I lay broad awaking :

But all is turn’d now through my gentleness,

Into a bitter fashion of forsaking ;

And I have leave to go of her goodness ;

And she also to use new fangleness.

But since that I unkindly so am served :

How like you this, what hath she now deserved ?

My Lute, Awake!

My lute awake, perform the last

Labour, that thou and I shall waste,

And end that I have now begun :

And when this song is sung and past,

My lute! be still, for I have done.

As to be heard where ear is none ;

As lead to grave in marble stone ;

My song may pierce her heart as soon.

Should we then sigh, or sing, or moan?

No, no, my lute! for I have done.

The rocks do not so cruelly

Repulse the waves continually,

As she my suit and affection :

So that I am past remedy ;

Whereby my lute and I have done.

Proud of the spoil that thou hast got

Of simple hearts through Love’s shot,

By whom, unkind, thou hast them won :

Think not he hath his bow forgot,

Although my lute and I have done.

Vengeance shall fall on thy disdain,

That makest but game on earnest pain ;

Think not alone under the sun

Unquit to cause thy lovers plain ;

Although my lute and I have done.

May chance thee lie withered and old

The winter nights, that are so cold,

Plaining in vain unto the moon ;

Thy wishes then dare not be told :

Care then who list, for I have done.

And then may chance thee to repent

The time that thou hast lost and spent,

To cause thy lovers sigh and swoon :

Then shalt thou know beauty but lent,

And wish and want as I have done.

Now cease, my lute! this is the last

Labour, that thou and I shall waste ;

And ended is that we begun:

Now is this song both sung and past ;

My lute! be still, for I have done.

Forget not Yet

Of such a truth as I have meant ;

My great travail so gladly spent,

Forget not yet!

Forget not yet when first began

The weary life ye know, since whan

The suit, the service none tell can ;

Forget not yet!

Forget not yet the great assays,

The cruel wrong, the scornful ways,

The painful patience in delays,

Forget not yet!

Forget not! oh ! forget not this,

How long ago hath been, and is

The mind that never meant amiss

Forget not yet!

Forget not then thine own approv’d,

The which so long hath thee so lov’d,

Whose steadfast faith yet never mov’d :Forget not this!

Blame not my Lute

Blame not my Lute ! for he must sound

Of this or that as liketh me ;

For lack of wit the Lute is bound

To give such tunes as pleaseth me ;

Though my songs be somewhat strange,

And speak such words as touch thy change,

Blame not my Lute !

My Lute ! alas ! doth not offend,

Though that perforce he must agree

To sound such tunes as I intend,

To sing to them that heareth me ;

Then though my songs be somewhat plain,

And toucheth some that use to feign,

Blame not my Lute !

My Lute and strings may not deny

But as I strike they must obey ;

Break not them then so wrongfully,

But wreak thyself some other way ;

And though the songs which I indite

Do quit thy change with rightful spite,

Blame not my Lute !

Spite asketh spite, and changing change,

And falsèd faith must needs be known ;

The fault so great, the case so strange ;

Of right it must abroad be blown :

Then since that by thine own desart

My songs do tell how true thou art,

Blame not my Lute !

Blame but thyself that hast misdone,

And well deservèd to have blame ;

Change thou thy way, so evil begone,

And then my Lute shall sound that same ;

But if ’till then my fingers play,

By thy desert their wonted way,

Blame not my Lute !

Farewell ! unknown ; for though thou break

My strings in spite with great disdain,

Yet have I found out for thy sake,

Strings for to string my Lute again :

And if, perchance, this sely rhyme

Do make thee blush, at any time,

Blame not my Lute !

Stand whoso List

Stand, whoso list, upon the slipper wheel

Of high estate ; and let me here rejoice,

And use my life in quietness each dele,*

Unknown in court that hath the wanton toys :

In hidden place my time shall slowly pass,

And when my years be past withouten noise,

Let me die old after the common trace ;

For gripes of death doth he too hardly pass,

That knowen is to all, but to himself, alas,

He dieth unknown, dasèd with dreadful face.

Source Text

Yeowell, James, Ed. The Poetical Works of Sir Thomas Wyatt. London: George Bell and Sons, 1904, is licensed under no known copyright.