Anglo-Norman Literature

|

Introduction

by D.J. Kingdon

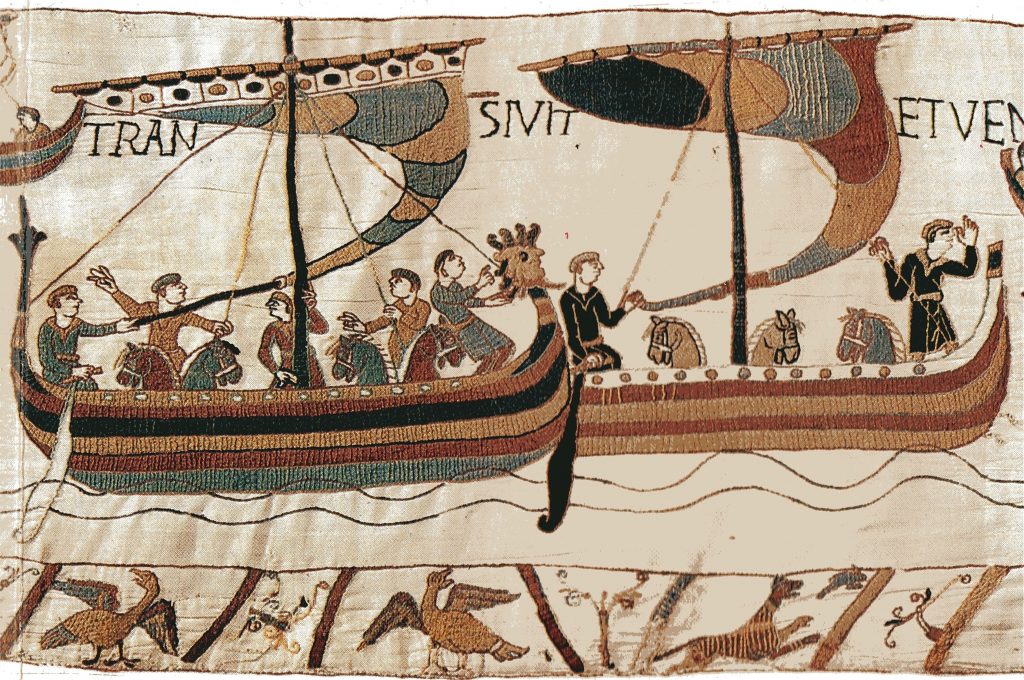

In 1066, the Normans led by William the Conqueror defeated the English at the Battle of Hastings in Southern England. It is important to note again that the Normans were originally the “Norsemen” who invaded France sacking and pillaging as they had done so in England. These were similar to the Norsemen who had destroyed Northumbria in the ninth century. When they invaded France, however, there was a difference. The marauders led by Rollo were defeated by the Franks in the Battle of Chartres in 911, and the Frankish King, Charles the III, signed a treaty in which they were given Rouen and the area of present-day Upper Normandy. Here, the once beserk warriors intermarried, abandoned their own culture and began to speak French.

Within a century, they had adopted French ideals and customs and had become a very polished and intellectual European people. It is said that the union of Norse and Gallic blood had produced a culture that had the best qualities of both—-the strength and energy of one and the curiosity and imagination of the other. So when William came with his Normans, they were hardly the “heathens” who had sacked Northumbria over a century previously. They brought an intellectual curiosity to England and a cosmopolitan vision of the world. The Norman conquest led to social, cultural and political upheavals in England. It signalled the end of the Old English language as it absorbed more French words and idioms. This invasion removed the English ruling class and replaced it with a very foreign monarchy. This brought about a complete change in the English culture and language. Latin remained as the language of the Church and learning while French became the language of the aristocracy (though intermarriage and exchanges with servants meant one had to engage in some bilingualism). There were various dialects of the Celtic language still spoken in areas like Cornwall, Scotland and Wales. Literature during this time concerned itself with mainly three subjects: religion, courtly love, and King Arthur.

The Anglo-Norman aristocracy was especially enamoured with the many Celtic legends that had been passed down for hundreds of years. The 12th century poets, Thomas of England, Marie de France and Chretien de Troyes all told that they were influenced by the stories of this ancient oral tradition. It was these three writers who were mainly responsible for the “romance” genre that has become so synonymous with the writing of this time period. They took some inspiration from the court of Henry II and his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine (who had been the wife of Louis VII of France and was very well educated and liberal for her time) but mostly, they were inspired by a remarkable tale of a King named Arthur which was included in a work called The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Geoffrey claimed that it had been based on a Welsh book (one that has never been found and perhaps never existed). It is now believed that he based his history on Celtic oral stories, mixed with bits of Roman history but it is more evident now that he wrote out of his own creative imagination.

The majority of the romances out of this Anglo-Norman period rely on the idea of a knight who proves his worth through his noble character and bravery rather than having had an aristocratic birthright. The Anglo Norman era in England also marked a time when many people turned to more personal encounters with God. This led a number of men and women (many of noble birth) to become anchorites or hermits choosing to live alone or in small groups simply to commune with God. But even this movement was compared by the clergy to the same sort of “knightly quest”, only this time it was the anchorite who duelled not with a knight but with temptation and evil. Or, in other texts, it is Christ who comes as a knight to save souls grappling with the darkness of wickedness.