17 Accessibility in Online Learning

Author’s NoteThis chapter was originally published as a chapter in the open-access eBook Thriving Online: A Guide for Busy Educators (Kay & Hunter, 2022; Power, 2022b). |

Introduction

![]() I have been designing and building online courses and digital learning resources for many years, and I am still learning new ways to make my resources as engaging and effective as possible for all of my students. An important area that I have been concentrating on in recent years is Digital Accessibility. One thing that I have learned is that it can be fairly easy to maximize the accessibility of our courses by following a few simple guidelines.

I have been designing and building online courses and digital learning resources for many years, and I am still learning new ways to make my resources as engaging and effective as possible for all of my students. An important area that I have been concentrating on in recent years is Digital Accessibility. One thing that I have learned is that it can be fairly easy to maximize the accessibility of our courses by following a few simple guidelines.

Why Accessibility Matters

For me, accessibility issues are something that started out as a professional interest. While working as an instructional developer at College of the North Atlantic-Qatar, I had the opportunity to learn about creating accessible documents through a professional development opportunity hosted by the Mada Assistive Technology Centre (Mada, 2017). While working with the Online Learning team at the Fraser Health Authority, I had the opportunity to explore accessibility issues in education more deeply by participating in the University of Southampton’s Digital Accessibility: Enabling Participation in the Information Society course (FutureLearn, n.d.). But, in recent years my interest has become more personal because I have two children with very different accessibility needs. I have also worked with students who have had documented accessibility needs, and I suspect that there have been many others who had needs that they either had not disclosed, or that they themselves were not even aware of.

It is likely that you will be working with students who have either documented, undisclosed, or perhaps undiagnosed needs that will be impacted by how you prepare and present your digital learning resources. As Doyle (2021) points out, “22% of Canadians over the age of 15 live with at least one disability that limits their everyday activities.” According to Dyslexia Canada (n.d.), “15-20% of the population has a language-based learning disability,” such as Dyslexia, meaning that nearly one in five of your students will likely be impacted by basic readability accessibility accommodations when creating your digital learning resources. Many Canadian jurisdictions have already enacted legislation dictating Digital Accessibility standards for instructional design of courses, as well as for digitally-mediated communications with our students, their parents, our colleagues, and the general public. In Canada, Ontario was the first province to explicitly codify Digital Accessibility standards through the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA, 2005). Provinces such as Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Quebec all have similar existing laws, while others such as British Columbia have legislation in the proposal stages (Doyle, 2021). Most of the standards that these provinces have put forth are based on the World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (W3C, 2022).

It is unreasonable to expect that all teachers will be well-versed in all of the web-content authoring guidelines or the range of digital tools available to support the variety of accessibility needs of their students. However, it is important for everyone to be aware of certain basic accessibility standards. In some jurisdictions, you may be required to meet these basic standards whether or not you are aware of a particular student who needs accommodations (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2016). These efforts represent small changes in practice that benefit all of our students, not just those with diagnosed needs.

Guidelines for Creating Digital Learning Resources

The following guidelines are based on the WCAG 2.1 standards (W3C, n.d.). These are all steps that anyone can take without investing in specialized software or learning additional web-coding skills.

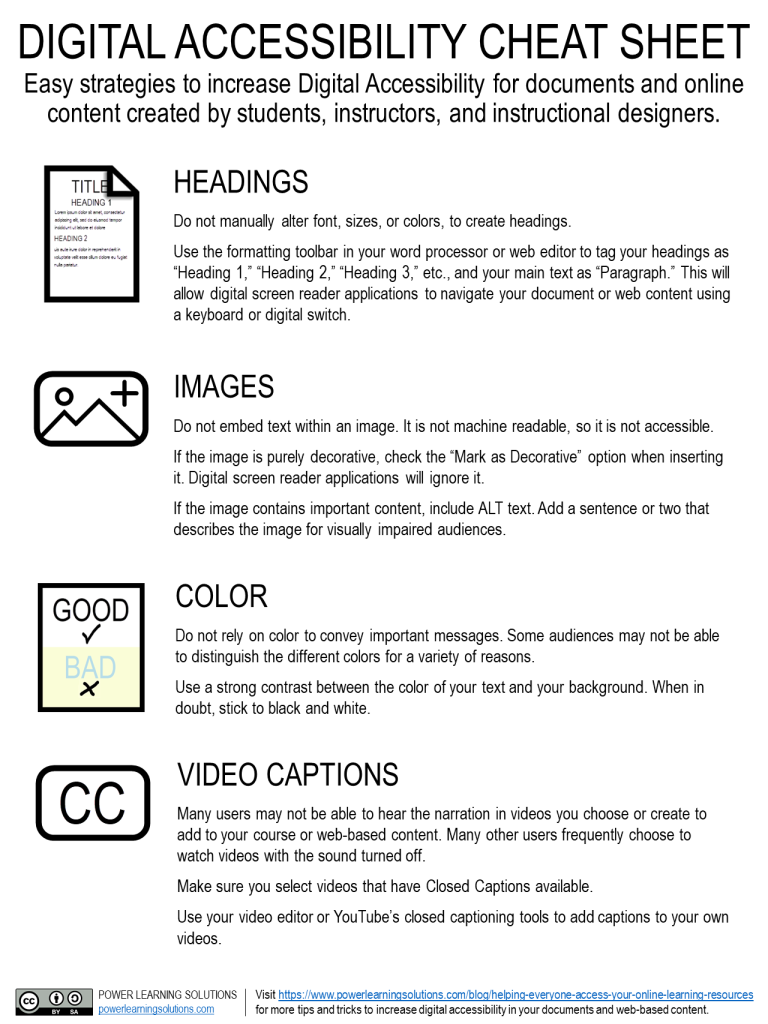

- Properly format and tag headings and text. Whether you are creating a word processor document, a PDF, a PowerPoint presentation, or a web page (including a page in a learning management system), you should avoid manually formatting the font, size, or color of your text to create document headings (Pennsylvania State University, 2021). Use the formatting toolbar in your word processor or web editor to tag your headings as “Heading 1,” “Heading 2,” “Heading 3,” etc., and your main text as “Paragraph.” This will allow digital screen reader applications to navigate your document or web content using a keyboard or digital switch. Sticking to the default paragraph and heading tags will also enable your students to use their own device’s accessibility settings, or browser plugins like the Open Dyslexic font (abbiecod.es, 2021; OpenDyslexic.org, n.d.), to adjust your digital reading materials to meet their individual needs.

- Add ALT-text and avoid embedding a lot of text within images. If you include an image in your document or web page, be sure to add alternate (ALT) text to the image (Harvard University, 2022). You can usually do this by selecting the appropriate option when inserting the image, or by right-clicking on the image. Your ALT-text should be a short (1-2 sentences, at most) description of what the image is about. This text will be read aloud to students if they are using a screen reader application, which is beneficial to visually impaired students. If the image is purely decorative, and your document or web editor provides the option, check the box to tag the image as “decorative” so that a screen reader will ignore it. Keep in mind that any text contained in the image itself is not machine-readable – so it is not accessible. Thus, avoid embedding important text within an image.

- Be careful when using color. Colors do not always display the way that we intend them to on everyone’s screen. Some of our students may also have visual impairments that make it difficult to read colored text (Morton, 2016). With this in mind, you should avoid using colored text to create emphasis, as that emphasis will not be apparent to some students. You should also be careful to maximize the contrast ratio (called color-contrast ratio) between your text and the background. Some color combinations may make it difficult to read the text. When in doubt, stick to black text on a white background. Many learning management systems will point out color-contrast issues when using the built-in accessibility checker. You can also use a free Color Contrast Analyzer like the one shared by the Paciello Group (n.d.) to check your documents and web pages.

- Check your reading order. When you create a document, PowerPoint presentation, or web page, the intended reading order for your content may be apparent to “visual” readers. However, this may not be the case for anyone using a screen reader application (Colorado State University, 2022). Reading order is often impacted by the order in which you actually placed the items on the page when creating the document (especially when creating slideshow presentations). One trick to ensure the correct reading order is to keep things linear on the page or screen, as screen readers will read the content from top-to-bottom by default. Another strategy is to avoid using tables to present content, unless you are presenting statistical data. (Tables need to be properly formatted with tagged header rows or columns, or they become confusing when using a screen reader.) Built-in Accessibility Checkers in word processors, PowerPoint, PDF editors, and web editors often have the ability to identify potential issues with the reading order of content.

- Make sure videos have Closed Captions. Many users may not be able to hear the narration in videos you choose or create to add to your course or web-based content. Many other users frequently choose to watch videos with the sound turned off. Make sure you select videos that have Closed Captions available. Use your video editor or YouTube’s closed captioning tools (Google, 2022) to add captions to your own videos

- Use an Accessibility Checker. Most word processing such as Microsoft Word (Microsoft, 2022a), web editing applications, and learning management systems such as Canvas (Instructure, 2022) now include an Accessibility Checker tool. It is often as easy to use as the spell checker. While an Accessibility Checker is not perfect, and may not detect compatibility issues with advanced accessibility tools that some of your students may use, it will pick up many common issues such as color-contrast ratios for text, missing table headers, and missing ALT-text for images. The Accessibility Checker will often provide suggestions or simple click-through options to help you resolve any issues detected.

These general guidelines are summarized in Power’s (2020) downloadable Digital Accessibility Cheat Sheet.

Activities

|

|

General Resources

Accessible Digital Documents and Websites and Accessibility in E-Learning

- The Council of Ontario Universities (2017a, b) provides a number of excellent resources to help you make your online teaching and learning resources are accessible to all learners, and AODA compliant.

BCampus Open Education Accessibility Toolkit

- BCampus (Coolidge, et al., 2018) recently published an Open Access eBook on how to make digital learning resources, such as eBooks, compliant with digital accessibility guidelines.

Google for Education Accessibility Resources

- Want to learn more about maximizing Digital Accessibility in your Google Classroom, or when using Google Apps for Education? Google for Education (n.d.) provides a two-page PDF with overviews and links to their accessibility resources for teachers and students.

Power Learning Solutions Digital Accessibility Resources

- Looking for more tips, tricks, and resources to help you improve the Digital Accessibility compliance of your digital learning resources? On my website, you will find an ever-growing list of resources, including recorded webinar presentations, tutorial videos, and links to tools (Power, 2022).

Understanding WCAG Compliance Checkers and Their Shortfalls

- Want to evaluate the Digital Accessibility compliance of your web-based learning resources, but there is no Accessibility Checker built into your platform? Essential Accessibility (2018) provides a good overview of how online accessibility checkers work, along with links to some free online accessibility checking tools, and a good must-have WCAG compliance checklist.

|

References

abbiecod.es (2021, June 27). OpenDyslexic for Chrome (Version 12.0.0). [Web browser extension]. Chrome Web Store. https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/opendyslexic-for-chrome/cdnapgfjopgaggbmfgbiinmmbdcglnam?hl=en

Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (2005, S.O. 2005, c. 11). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/05a11

Coolidge, A., Doner, S., & Robertson, T. (2018). BCampus Open Education Accessibility Toolkit. [eBook]. BCampus. https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/

Colorado State University (2022). Reading Order. [Web page]. Accessibility by Design. https://accessibility.colostate.edu/reading-order/

Council of Ontario Universities (2017a). Accessible Digital Documents & Websites. [Web page]. Accessible Campus. http://www.accessiblecampus.ca/reference-library/accessible-digital-documents-websites/ (Links to an external site.)

Council of Ontario Universities (2017b). Accessibility in E-Learning. [Web page]. Accessible Campus. http://www.accessiblecampus.ca/tools-resources/educators-tool-kit/course-planning/accessibility-in-e-learning/

Doyle, J. (2021, May 26). A Complete Overview of Canada’s Accessibility Laws. [Web log post]. Siteimprove. https://siteimprove.com/en-ca/blog/a-complete-overview-of-canada-s-accessibility-laws/

Dyslexia Canada (n.d.). Dyslexia Basics. [Web page]. https://www.dyslexiacanada.org/en/dyslexia-basics

Essential Accessibility (2018, May 2). Understanding WCAG Compliance Checkers and Their Shortfalls. [Web blog post]. Essential Accessibility. https://www.essentialaccessibility.com/blog/wcag-compliance-checkers

FutureLearn (n.d.). Digital Accessibility: Enabling Participation in the Information Society. [Massive Open Online Course]. https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/digital-accessibility

Google (2021, July 27). Screen Reader (Version 53.0.2784.13). [Web browser extension]. Chrome Web Store. https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/screen-reader/kgejglhpjiefppelpmljglcjbhoiplfn

Google (2022). Add subtitles and captions. [Web page]. YouTube Help. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2734796?hl=en

Google for Education (n.d.). Working to make Google for Education more accessible for everyone. [PDF file]. https://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/education_accessibility.pdf

Harvard University (2022). Write good Alt Text to describe images. [Web page]. Digital Accessibility. https://accessibility.huit.harvard.edu/describe-content-images

Instructure (2022). How do I use the Accessibility Checker in the Rich Content Editor as an instructor? [Web page]. Instructure Community. https://community.canvaslms.com/t5/Instructor-Guide/How-do-I-use-the-Accessibility-Checker-in-the-Rich-Content/ta-p/820

Kay, R. H., & Hunter, W.J. (Eds.), (2022). Thriving Online: A Guide for Busy Educators. Ontario Tech University. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/aguideforbusyeducators/

Mada (2021). Mada Assistive Technology Centre. [Web page]. https://mada.org.qa/en/Pages/default.aspx

Microsoft (2022a). Improve accessibility with the Accessibility Checker. [Web page]. Office Support. https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/improve-accessibility-with-the-accessibility-checker-a16f6de0-2f39-4a2b-8bd8-5ad801426c7f

Microsoft (2022b). Listen to your Word documents. [Web page]. Office Support. https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/listen-to-your-word-documents-5a2de7f3-1ef4-4795-b24e-64fc2731b001

Morton, R. (2016, June 17). Colour contrast – why does it matter? [Web log post]. Accessibility in Government. https://accessibility.blog.gov.uk/2016/06/17/colour-contrast-why-does-it-matter/

NV Access (2021). Join the NVDA Revolution! Finally, a Fast, Functional, & Totally Free Screen Reader. [Web page]. https://www.nvaccess.org/about-nvda/

Ontario Human Rights Commission (2016, January 6). New documentation guidelines for accommodating students with mental health disabilities. [Web page]. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/news_centre/new-documentation-guidelines-accommodating-students-mental-health-disabilities

OpenDyslexic.org (n.d.). OpenDyslexic: A typeface for Dyslexia. [Web page]. https://opendyslexic.org/

The Paciello Group (n.d.). Colour Contrast Analyzer (CCA). [Web page]. https://developer.paciellogroup.com/resources/contrastanalyser/

Pennsylvania State University (2021). Headings and Subheadings. [Web page]. Accessibility. https://accessibility.psu.edu/headings/

Power, R. (2020, February 13). Helping Everyone Access Your Online Learning Resources. [Web log post]. Power Learning Solutions. https://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/blog/helping-everyone-access-your-online-learning-resources

Power, R. (2022a). Digital Accessibility. [Web Page]. Power Learning Solutions. https://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/digital-accessibility.html

Power, R. (2022b). Accessibility in Online Learning. In R. H. Kay & W.J. Hunter (Eds.), Thriving Online: A Guide for Busy Educators (pp. 101-108). Ontario Tech University. https://doi.org/10.51357/ERZM7438

Power, R. (Ed.). (2024). The ALT Text: Accessible Learning with Technology. Power Learning Solutions. ISBN 978-1-7390190-2-0. https://pressbooks.pub/thealttext/

W3C (2022). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). [Web page]. https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/

Activity 1: Testing with a Screen Reader

Activity 1: Testing with a Screen Reader

Additional Resources for Developing Accessible Learning

Additional Resources for Developing Accessible Learning