7 Lennoxvale, off the Malone Road, in Belfast, always “Lennoxvale” to the family, was the home of Julius Loewenthal, his Belfast-born wife Jane, the recipient of these letters, and their 8 children. ‘Lennoxvale’ was also a sufficient address for mail from another continent; the boat chosen for its voyage being indicated above the address on the envelope. The back of each envelope is usually dated in a different hand, presumably Jane’s.

The writer, John McCaldin Loewenthal, Jack to his friends and JMcC to family to distinguish him from another John, his cousin, John Jacoby (JJ), was their eldest son.

After the period of the voyages, vividly described in these letters, JMcC settled down in Belfast in University Square. His beloved younger brother “Julie” died in Brazil of yellow fever during a similar voyage in 1896. Whether his death played a role in JMcC’s decision to settle we do not know. Settle he did, followed by marriage at the age of 39. The wedding was in Hamburg, to Elsa, a cousin on Julius’ side of the family. The couple moved to Marlborough Park, Belfast, where they had four daughters – in sequence: Helen, Amélie, Joan, and Margaret (always known as Peggy).

When Julius died in 1916 the young family moved into Lennoxvale. Something of life there is brought alive in the youngest daughter’s memoir, From Belfast to Belsen and Beyond. Lennoxvale, a much-loved house, remained the family home until, in turn, JMcC’s death in 1951 (the picture shows Lennoxvale with two of JMcC’s daughters; Peggy seated, and Joan standing).

Amélie, their second daughter must have acquired the letters when that home of two generations of Loewenthals was broken up. The Vice-chancellor of Queen’s University had his residence in Lennoxvale too. The Loewenthal home went to the University and became its School of Psychology, and in 2015, by now an administration building, the house still bore a plaque memorialising JMcC who had, long after the voyages, been honoured in 1939 with a Queen’s University M.A. in recognition of his contributions to Belfast life.

Amélie was always a hoarder of letters. Forty years later she, widow of an academic, in turn left her house, in Cambridge. The move meant another clear-out and distribution of items to her four sons. One of these items was a battered old suitcase of Elsa’s which ended up in, second son, Robert’s Macclesfield garage.

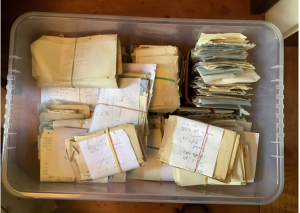

The suitcase was stuffed with letters and other memorabilia; Robert’s school reports, childhood postcards, some photographs and many negatives. The bulk of the letters were between Amélie and Dixon Boyd and their friends and relatives. Their courting missives, wartime correspondence and later holiday reports predominated. There was, however, some earlier material. When leaving the suitcase, Amélie drew specific attention to a group of her father’s letters from South America – those which now form this volume.

But, Robert was a busy man or thought himself a busy man. Amélie died. The garage became cluttered with mid-life bicycles, garden tools, and the detritus of university-leaving children; yet another generation. The contents of the suitcase migrated to a cupboard in the ex-bedroom of one of these, JMcC’s great-grandson. Robert had read a few of the letters at the time of that migration and even transcribed a summary of one voyage but did no more until the cycle of life brought Amélie’s four children – four sons – into their phase of retirement and more imminent death. More time and less time!

Robert began to share the contents of the suitcase with his brothers, especially letters between their parents in coping with war-time separation as young parents and, with John, the eldest, who was then dying in his turn, evidences of his early life. Some of the letters were from friends and relatives and in German

Enter Michelle, Peggy’s daughter and JMcC’s youngest grandchild born the year before he died. She was home in Cambridge from Australia. She came to Macclesfield and, brought up in Vienna, kindly translated, including difficult early missives in “Kurrent” (German cursive) script from Julius’ family. The same visit, she and Robert began to seriously engage with the letters of JMcC’s voyages. It was clear she had the skills and interest to take engagement with them to an entirely new level: the boats, the friends, the peripatetic life. But, her stay was short.

Came the pandemic. Robert was locked down on the island of Tiree, one of the smaller Hebrides. He had the letters with him. Michelle was stuck in Melbourne unable to come to Cambridge. What better Covid project? Robert could image and send, using WhatsApp, letters laid out on the kitchen table, with the help of low denomination weights from ancient kitchen scales. This had to be done at mid-day when the light was sufficiently bright to avoid blurring. Michelle could decipher occasionally faded handwriting using her expertise as a radiologist in handling imaging tools. She could then, with the help of the internet, integrate the letters into their local and wider context. After a morning swim, WhatsApping for Michelle became a daily pleasure. A century and more since their writing did not seem very long. It was also poignant to remember that another of JMcC’s brothers, Jim, had died in 1919, twenty years after the voyages, in another pandemic, the Spanish Influenza of 1918

Covid, and John’s death which brought cousins together, also provided an unexpected stimulus for all JMcC’s surviving grandchildren to get together on Zoom and contemplate our shared grandparent. And, as we discussed the possibility of sharing more widely aspects of 19th-century commerce brought alive in JMcC’s vivid prose (and occasional verse), we realised that a great-grandchild (Charles Watkinson) might enable us to reach that goal. This volume is the result.