77

18930915 See an image of this letter, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/vh8w-dr59

S.S. “Magdalena” 15th Sep. ‘93

My dear Mother,

By this time you will know more about the Revolution in Brazil than we do. When we arrived in Pernambuco, from which place I posted my last letter to you, there were rumors of trouble somewhere. Cable communication was interrupted & it was said that the Province of Rio Grande, always in hot water, had revolted once more. At Maceió, the new next port of call we learned that the fleet had sided with the Rebels & that we might have difficulty in entering Rio.[1] So we were all up early on Monday morning & there was much excited speculation among the passengers as to what might happen.[2] We steamed up to the fort near the entrance & awaited the usual visit, but no visit came, & the English gun-boat “Sirius” at once signalled to us that no communication was allowed with the shore, but that we might go up to our anchorage & they wd send an armed escort on board, & that they were prepared to take German subjects, as well as English, under their protection.[3] The English gun-boats “Racer” & “Beagle” were also lying near,[4] & soon the pinnace[5] from the “Sirius” was alongside with a lieutenant & some blue-jackets, & we proceeded to the usual anchorage in the inner harbour rather more than a mile from the shore. There were likewise three Italian men-of-war, & one French, signalling by flags & semaphore to one another. The customary vast amount of shipping was anchored round, but we noticed that none of the steamers were discharging or taking in cargo. On the north side of the Bay the Brazilian fleet was in line, to-gether with all the National coasting steamers, which they had taken possession of, requisitioning their coals & stores. We learned from the officers of the “Sirius” that there had not been much fighting in Rio itself but a hot struggle had been going on for several days on the north side, at Nitheroy, where there is a Government arsenal which had been taken & re-taken more than once by the opposing factions.[6] Later in the day & after much interchange of communications between the fleet & the “Magdalena”, we sent some of our Rio passengers & the mails ashore, escorted by the pinnace flying their white ensign, our own boats proudly showing their Union Jack, & they were not molested. That night the Brazilian fleet kept up a vigorous canonade on the forts at Nitheroy, & in the morning between 8 & 9 o’c. there was quite a bombardment, answered sharply by the guns on shore.[7] We were anchored a couple of miles away & we watched it all through glasses without being able to discover whether the fleet had succeeded in landing troops & retaking the arsenal, which was evidently their object. During the night the electric search lights flashed frequently over the Bay & we heard a desultory firing.

By the Admiral’s orders no one was to be away from the ship after dark. Boats flying a foreign flag were unmolested during the day-time, but two nights before some men from the Italian Legation were returning in a boat from the man-of-war after dinner & they were fired on & one killed. Next day the Italian Admiral sent a boat ashore to demand £5000 indemnity, which was promptly paid.

The Agent managed to come off from the shore & to secure a couple of lighters[8], but we only got about half of our cargo out & we left the lighters anchored there in the Bay. There was no coal to be had either but fortunately we had enough to take us on.

On Tuesday morning, the 2nd officer was going ashore in the steam-launch & just as he went down the ladder he asked me wd I care to go with him. I did not wait for a second invitation but slipped into the launch. The Captain was not pleased about it, I heard afterwards, but there really was no risk. We came ashore & everything seemed to be going on almost as usual. Most of the shops were open & the trams were running, but the Banks had only half a door open, ready to close in case of a row. I saw some of my friends. Youle pressed me to stay overnight, but luckily I preferred returning to the ship.[9] Luckily – because though we expected to be detained several days, we were informed that the Brazilian Admiral had given formal notice of his intention to bombard the town & the United Foreign Ministers had only been able to obtain a postponement of the bombardment till 8 o’c. next morning, so our Admiral advised the Captn of the “Magdalena” to clear out at day-break, which we did.[10] Had I remained ashore, I shd have been left behind.

As it was the passengers for Santos – some twenty, including several ladies & children – were very much in a fix. They were making enquiries about some steamer to take them to Santos & some had gone ashore & left their baggage on board, while some had remained on board & sent their baggage ashore. Those who had staid with us were transferred at 4 o’c in the morning to a cargo boat belonging to one of our passengers, a Mr Holland, who ordered it to clear out at once, & we left immediately afterwards. As we sailed we saw the foreign men-of-war changing their position, presumably to be out of the line of fire.

Of what has happened since we are of course in entire ignorance. The general opinion seems to be that the Navy, under Mello, backed by Rio Grande, will speedily gain the upper hand, & the President Floriano Peixoto will be deposed.[11]

We have one refugee with us – a little shrimp of a man who has done more harm to Brazil in recent years than any other – Ruy Barboza, finance minister, some say of the last cabinet, some say (& I think) of the present one.[12] But in any case it looks like the rats leaving the sinking ship.

Last time I went north he was passenger from Rio to Bahia, his native town, where he was received with a steam tender decked with bunting, bands of music, rockets, huge bouquets with satin streamers & vivas to the “ilustre Bahiano”.

I did not see Murly Gotto at Rio but I left Miss Gotto’s parcel, with a note, at the Roy. Mail Agency & they were to deliver it.[13] Neither did I see Spann, Allens, or McKinnels, none of whom were in town that day.[14]

You see we have had some little excitement. As likely the ship has not been wired from any Brazilian port I purpose sending a telegram to the office on arrival at B. Aires.

We are now speculating as to the possibility of quarantine at the River Plate. Recent Roy. Mail ships have had to undergo it – why I don’t know unless on acct. of cholera in Europe. Moreover we had to leave Rio without a bill of health or other customary papers.

At Pernambuco I saw Keiller, who had quite recovered from a severe attack of yellow fever, & many other friends.[15] At Bahia I saw no one because it was a strict church holiday & I had not been able to wire from Pernambuco for anyone to meet me.

Since leaving Rio we have had rather rough weather & the fiddles have been on the tables for the first time.[16]

The voyage altogether has been very pleasant. Julian has not suffered much this time from head-aches though he had one or two bad ones.[17]

Now I hope soon to have settled down to work. I trust the Pater has done well & will soon be home in good health & spirits.

Best love to all

Jack

- The journey south to the River Plate and Buenos Aires continues – first port is Maceió: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macei%C3%B3 ↵

- Presumably outside Rio de Janeiro (Monday 11th September). ↵

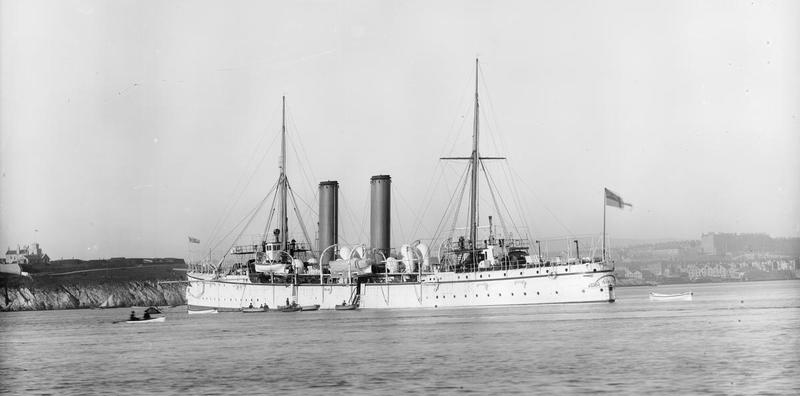

- HMS Sirius was an Apollo-class cruiser of the British Royal Navy which served from 1892 to 1918 in various colonial posts such as the South and West African coastlines, as well as off the British Isles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Sirius_(1890) ↵

- HMS Racer was a Royal Navy Mariner-class composite screw gunvessel of 8 guns (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Racer_(1884)) and HMS Beagle, launched 1889, was a Beagle-class 8-gun screw steel sloop (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beagle-class_sloop). ↵

- a small boat, typically with sails and/or several oars, forming part of the equipment of a warship or other large vessel. ↵

- Actually Niterói, across the bay northeast of Rio de Janeiro. ↵

- The monarchist navy revolt in 1893 damaged productive activities and forced the transfer of the capital's headquarters to Petrópolis. ↵

- flat-bottomed barge or other unpowered boat used to transfer goods to and from ships in harbour ↵

- Probably Frank (Schwind) Youle (b 1867, d 1900 Rio de Janeiro). See Index to People. ↵

- This would have been Wednesday 13th September (see below) – when bombardment of the fortress held by the Army began. ↵

- Rebels joined forces with the naval rebellion of Admiral Custódio de Melo to oppose the republican regime of Floriano Vieira Peixoto. It was a very bloody revolt – harshly suppressed in the end (not as predicted by JMcC). https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/federalist-revolt-1893. More broadly, this was the second Brazilian Naval Revolt which had started in March 1892, when thirteen generals sent a letter and manifesto to President Floriano. This document demanded new elections be called to fulfil the constitutional provision and ensure internal tranquillity in the nation. Floriano harshly suppressed the movement, ordering the arrest of their leaders. Thus, not legally solved, the political tensions increased. On September 13 (a Wednesday), the fortresses in Rio de Janeiro, held by the Army, began to be bombarded. The rebel forces' fleet consisted of navy vessels and civilian vessels of Brazilian and foreign companies. In the Navy, the rebels were the majority but faced strong opposition in the Army, where thousands of young people joined the battalions that supported President Floriano. State elites, especially Sao Paulo, were also in favor of Floriano: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolta_da_Armada ↵

- Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (b 5th November 1849, d 1st March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian polymath, diplomat, writer, jurist, and politician: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruy_Barbosa ↵

- This is Percy Murly Gotto, civil engineer and director of the Rio de Janeiro City Improvements company (see Index to People). Percy Murly Gotto’s brother, Arthur Charles Gotto (b 1853), lived in Belfast on the Malone Road and had given JMcC the introduction to Percy. I cannot find a record of a daughter but there could have been a Miss Gotto, niece of Percy, or else it was from Mrs Margaret Mary Gotto – Percy’s sister-in-law. ↵

- Adolf Spann was an external commercial agent- his company Adolf Spann & Co. facilitated the development of the Brazilian textiles industry and export. McKinnels JMcC had met on the steamer going to Pernambuco in 1890. ↵

- This is John Gibson Keiller (b 9 July 1865 Dundee, d 1897 Pernambuco), Fred Weinberg's future brother-in-law. See Index to People. ↵

- A fiddle in nautical settings is a guardrail used on a table during rough weather to prevent things from slipping off. ↵

- Julian Weinberg (see Index to People). ↵