Kinematics – Motion in Two Dimensions

Last Update: 12/01/2022

Kinematics of uniform circular motion

We know from kinematics that acceleration is a change in velocity, either in its magnitude or in its direction, or both. In a uniform circular motion, the direction of the velocity changes constantly, so there is always an associated acceleration, even though the magnitude of the velocity might be constant. You experience this acceleration yourself when you turn a corner in your car. (If you hold the wheel steady during a turn and move at a constant speed, you are in a uniform circular motion.) What you notice is a sideways acceleration because you and the car are changing direction. The sharper the curve and the greater your speed, the more noticeable this acceleration will become. In this section, we examine the direction and magnitude of that acceleration.

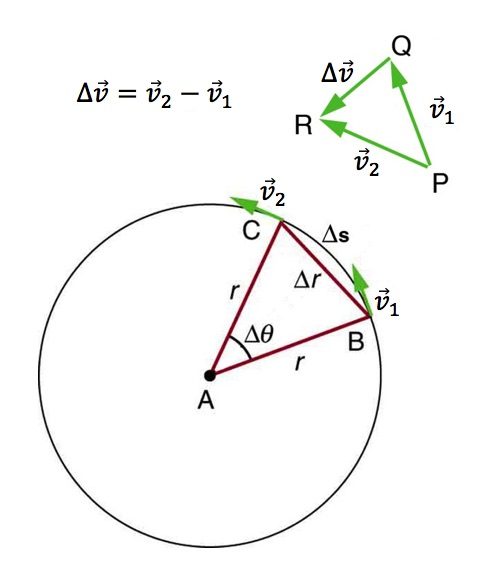

Figure 6.1 shows an object moving in a circular path at a constant speed. The direction of the instantaneous velocity is shown at two points along the path. Acceleration is in the direction of the change in velocity, which points directly toward the center of rotation (the center of the circular path). This pointing is apparent in the vector diagram in Figure 6.1. Notice that since the direction of velocity continuously changes, in order to find the direction of ![]() at a given instant, we need to subtract initial and final velocities that are infinitely close to one another. The velocities

at a given instant, we need to subtract initial and final velocities that are infinitely close to one another. The velocities ![]() and

and ![]() in Figure 6.1 are significantly apart to make the diagram more clear, but if they were truly infinitely close to one another, then the vector

in Figure 6.1 are significantly apart to make the diagram more clear, but if they were truly infinitely close to one another, then the vector ![]() would point exactly toward the center of the circular path. We call the acceleration of an object moving in a uniform circular motion, the centripetal acceleration. Centripetal means “toward the center” or “center seeking.”

would point exactly toward the center of the circular path. We call the acceleration of an object moving in a uniform circular motion, the centripetal acceleration. Centripetal means “toward the center” or “center seeking.”

The direction of centripetal acceleration is toward the center of the circular path, but what is its magnitude? Note that the triangle formed by the velocity vectors and the one formed by the radii r and Δs are similar. Once again, when ![]() and

and ![]() are infinitely close to one another, Δs and Δr become practically the same. Both the triangles ABC and PQR are isosceles triangles (two equal sides). The two equal sides of the velocity vector triangle are the speeds

are infinitely close to one another, Δs and Δr become practically the same. Both the triangles ABC and PQR are isosceles triangles (two equal sides). The two equal sides of the velocity vector triangle are the speeds ![]() and

and ![]() . Using the properties of two similar triangles, we obtain

. Using the properties of two similar triangles, we obtain

![]()

Magnitude of acceleration is ![]() , and so we first solve this expression for

, and so we first solve this expression for ![]()

![]()

Then we divide this by Δt, yielding

![]()

Finally, noting that ![]() and that

and that ![]() , we see that the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration is

, we see that the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration is

![]()

Centripetal Acceleration

Centripetal Acceleration

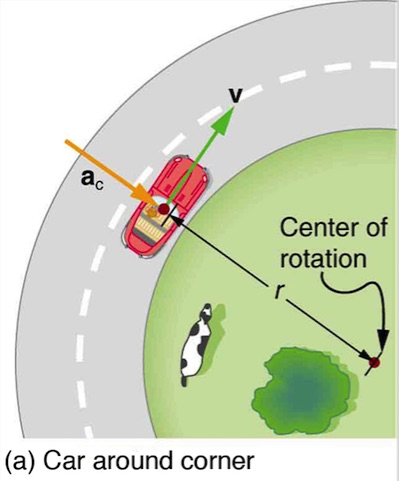

ac is the acceleration of an object in a circle of radius r at a speed v. So, centripetal acceleration is greater at high speeds and in sharp curves (smaller radius), as you have noticed when driving a car. But it is a bit surprising that ac is proportional to speed squared, implying, for example, that it is four times as hard to take a curve at 100 km/h than at 50 km/h. A sharp corner has a small radius so that ac is greater for tighter turns, as you have probably noticed.

Example 6.1 – How Does The Centripetal Acceleration Of A Car Around A Curve Compare With That Due To Gravity?

What is the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration of a car following a curve of radius 500 m at a speed of 25.0 m/s (about 90 km/h)? Compare the acceleration with that due to gravity for this fairly gentle curve taken at highway speed.

Strategy

The car following a circular path at constant speed is accelerated perpendicular to its velocity, as shown in Figure 6.2(a) . The magnitude of this centripetal acceleration is found by using

![]()

Solution

Entering the given values of v=25.0m/s and r=500m into this expression gives

![]()

![]()

Discussion

To compare this with the acceleration due to gravity, g=9.8 m/s2, we take the ratio of the two accelerations:

![]()

Thus ac = 0.128g. This is noticeable especially if you were not wearing a seat belt.

Video Example – Circular motion of a ball attached to a string

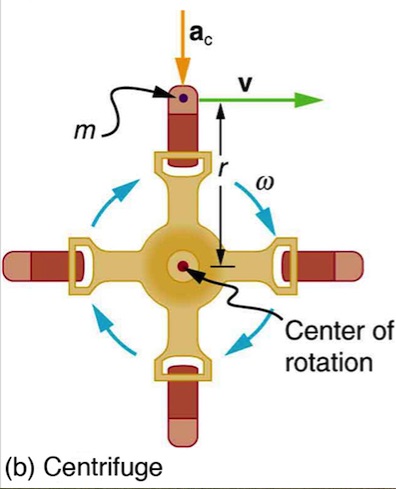

Example 6.2 – How Big Is the Centripetal Acceleration In An Ultracentrifuge?

Calculate the centripetal acceleration of a point 7.50 cm from the axis of an ultracentrifuge spinning at 7.5×104 rev/min. Determine the ratio of this acceleration to that due to gravity.

Strategy

A particle of mass in a centrifuge is rotating at constant angular velocity. It must be accelerated perpendicular to its velocity or it would continue in a straight line. See Figure 6.2(b). The magnitude of the necessary acceleration is found by using

![]()

Solution

The term rev/min stands for revolutions per minute. We can use this to find the speed of the particle in m/s. One revolution is a distance that is equal to the circumference of the circular path, 2πr. Therefore

![]()

Now the centripetal acceleration can be calculated.

![]()

![]()

Taking the ratio of ac to g yields

![]()

<span id=”MathJax-Element-51-Frame” class=”MathJax” style=”font-style: normal;font-weight: normal;line-height: normal;font-size: 14px;text-indent: 0px;text-align: left;text-transform: none;letter-spacing: normal;float: none;direction: ltr;max-width: none;max-height: none;min-width: 0px;min-height: 0px;border: 0px;padding: 0px;margin: 0px” role=”presentation” data-mathml=”

acacsize 12{a rSub { size 8{c} } } {}”>Discussion

This last result means that the centripetal acceleration is 472,000 times as strong as g. It is no wonder that centrifuges with such fast rotational speeds are called ultracentrifuges. The extremely large accelerations involved greatly decrease the time needed to cause the sedimentation of blood cells or other materials.

Attributions

This chapter contains material taken from “Openstax College Physics-Uniform Circular Motion and Gravitation by Openstax and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license. Download this book for free at Openstax-College Physics

To see what was changed, refer to the List of Changes.

problems

- [openstax unv. phys. vol. 1 – 4.60] A flywheel is rotating at 30 rev/s. What is the total angle, in radians, through which a point on the flywheel rotates in 40 s?

- [openstax unv. phys. vol. 1 – 4.64] A runner taking part in the 200-m dash must run around the end of a track that has a circular arc with a radius of curvature of 30.0 m. The runner starts the race at a constant speed. If she completes the 200-m dash in 23.2 s and runs at a constant speed throughout the race, what is her centripetal acceleration as she runs the curved portion of the track?

- [openstax unv. phys. vol. 1 – 4.65] What is the acceleration of Venus toward the Sun, assuming a circular orbit? Hint: You need to look up the numbers you need.

- [openstax unv. phys. vol. 1 – 4.67] A fan is rotating at a constant 360.0 rev/min. What is the magnitude of the acceleration of a point on one of its blades 10.0 cm from the axis of rotation?

- [openstax unv. phys. vol. 1 – 4.68] A point located on the second hand of a large clock has a centripetal acceleration of 0.10cm/s2. How far is the point from the axis of rotation of the second hand?