12.4 Fixed Income Securities: Bond Components and Valuation Formula

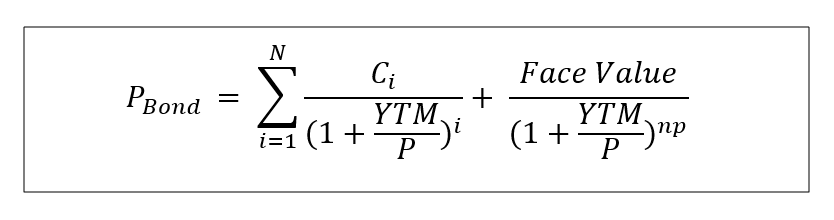

Since the coupon cash flow of a bond constitutes an annuity, the calculation of a bond’s dollar price involves a simple solution:

The above formula says that every (annuity) coupon payment plus the one-time face value payment are discounted and aggregated to present value, which is the bond’s price. This is based on our “valuation premise.” Here are some important terms to know:

Face Value = Maturity Value = Par Value = Principal: These phrases are synonymous and interchangeable. Maturity value is the amount of money the investor, or bondholder/lender, gets back when the bond matures. This represents, in most instances (and herewith) a one-time cash inflow to the investor.

Coupon Rate (C) = Interest Rate (I): This is the amount of interest that the bond pays. (An exception would be a variable rate, but we do not deal with that here.) The dollar amount paid is this rate times the face value. Thus, if the rate is 10% and the Face Value is $1,000, it will pay $100 per year. If this bond pays semi-annually, the investor will receive two $50 payments per year, one every six months. This represents an annuity series of cash flows for the life of the bond; this is the bond’s second set of cash flows.

Yield-to-Maturity (YTM) = Market Rate = Discount Rate: This is the market-determined rate at which the bond’s cash flows – both the Face Value and the coupon payments – are “priced,” or discounted, to present value. Do not confuse coupon and market rates; they are separate and mathematically distinct. The market yield will constantly change. Coupons are (generally) fixed.

We may think of Face Value and the bond’s Dollar Price in terms of $100s or $1,000s or any multiple thereof. Since the bond’s price is expressed in terms of 100% of the bond’s “Par” value, it doesn’t matter for calculation purposes, how many zeros we add on in an illustration or exercise. This will be demonstrated immediately below.

The bond trader will quote the bond in terms of a percent of par and will then ask the buyer or seller what the “size” of the trade is? In other words, how much they are dealing with. Of course, in reality, buying or selling a thousand, or a million, dollars’ worth of bonds matters a great deal. An example follows.

Creditors have better memories than debtors.

-Benjamin Franklin