13.6 Credit Ratings

Corporations are rated by credit-rating agencies that assess a corporation’s ability to service its debt (i.e., to pay interest and principal in full and on time) and, thus, to avoid a default and to ultimately keep bankruptcy at bay. This is a risk, which may also be referred to as “default risk.”

We have already examined three solvency ratios which attempt to provide some insight into this risk. Clearly, there are many more tools and considerations that enter into the process of credit analysis and rating. Companies must pay for this service, but not all do so, as some bond issues are too small to justify the expense, while others may be sold directly to institutional investors and thus do not require a rating.

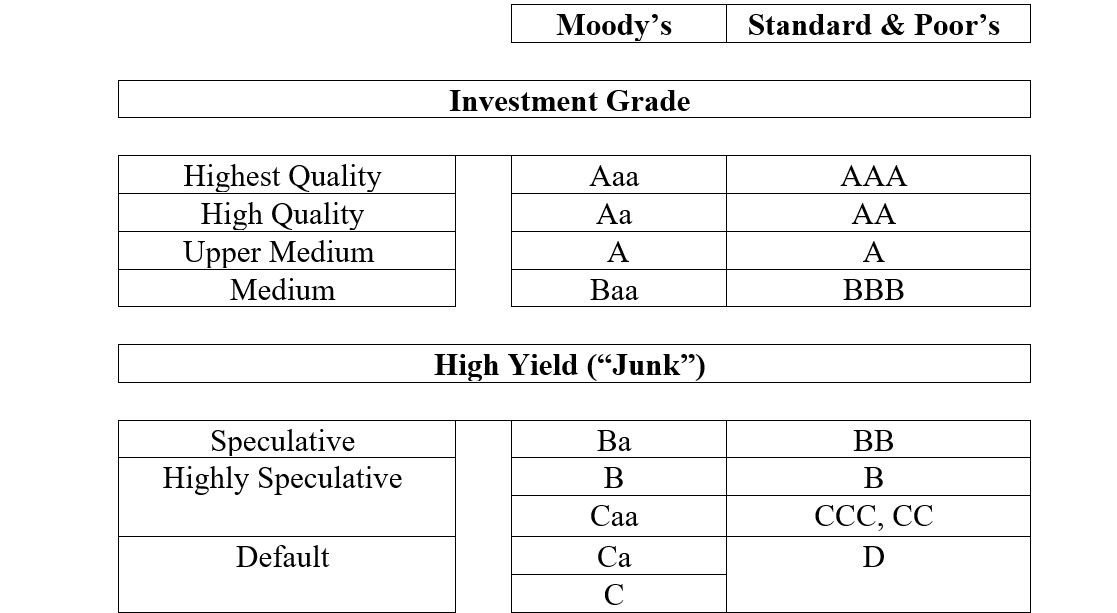

Today, there are two major rating agencies: Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Moody’s. Fitch is still a third agency, but it does not enjoy the market presence of the others. In addition, there are numerous nationally recognized statistical rating organizations or “NRSRO’s” that perform similar functions (see: https://www.sec.gov/ocr/ocr-current-nrsros.html). The agencies rate bonds on the scale illustrated below. As you will note, there are some differences in the rating scales, and, although not visible in the ratings themselves, the manners in which the agencies conduct their respective analyses and what they consider important also differ from one agency to the other. As a result, the agencies may not rate the same bond issuer the same.

Within each rating category, the agencies may append additional notation, such as “A-” in the case of S&P. This provides some further refinement to the ratings.

Note:

Ratings will clearly affect the bond’s yield – in inverse relation to the rating, with lower ratings generally bringing higher yields. That is to say that the lower the credit rating, the higher the default risk. A greater default risk means a lower dollar price, which, in turn means a higher yield.

The better the bond’s initial rating, the lower the bond’s coupon rate of interest, and, of course, the lower the issuer’s cost of debt capital; this is also true for the bond’s subsequent secondary market yield, (a.k.a. yield-to-maturity; YTM). Do not confuse coupon and market yields; they are separate. The coupon determines how much the interest bond pays, whereas the YTM is the ever-changing market discount rate which is used to price the bond.

The rating agencies do not collude or necessarily agree with one another; in some cases, the agencies may rate the same company somewhat differently. Interestingly, the bond market itself seems to understand what the true yield for a bond should be; indeed, yields often adjust long before a rating change (i.e., either an upgrade or a downgrade) announcement. Further, a bond’s rating is not necessarily “correct.”

In the case of municipal bonds, the agencies conduct similar analyses and provide similar ratings. The interpretation of municipal ratings, however, is somewhat different in practice, with municipal bonds less likely to default than their ratings might imply. In some instances, municipal bonds may be insured by private insurance companies, in most of which cases the bonds will therefore bear a “AAA” rating regardless of its intrinsic creditability. Most insurers are considered to be in the best financial health.

United States Treasury and Agency bonds are highly rated but are no longer perceived as being completely risk free. In 2011, Standard & Poor’s lowered its rating for Treasury Securities from AAA to AA+. The agency felt that the congressional deadlock in arriving at a budget agreement warranted the downgrade. Since then, the agency has not upgraded the rating back to AAA. The other rating agencies have kept the Treasury’s rating at AAA.

“Agencies” are considered slightly lower in quality than “Treasuries” and will therefore trade at very slightly higher yields. The markets “know” how to price their securities based on YTM and its associated default risk.

While the rating agencies do not provide the details of the manner in which they conduct their ratings, it is accepted that their formulae consist of a combination of the examination of the issuer’s financial health (based on its financial statements), its economic environment, and an examination of the bond’s covenants.

Covenants are agreed-upon terms to which the issuer assures it will adhere; in a way it is a restriction imposed by the lender in order to secure or strengthen his position. For instance, the issuer may assure the investors that its financial ratios will remain within certain parameters, or that it will not issue any further debt, which shall be senior to the issue at hand. In general, such negative covenants will also prohibit the firm from paying too much in dividends, selling or pledging assets to other lenders, maintaining collateral in good condition, or adding on more debt. Timely interest and principal payments would certainly be included in this category. These assurances are spelled out in the bond indenture, a legal document in which all the terms of the bond issue are spelled out, including the bond’s maturity and coupon interest rate.

Although a bond issuer, or borrower, may pay its bond interest in full and on time, which is to say it is not in default, any violation of any of the bond indenture’s covenants may be interpreted as a technical default and result in a downgrading of the bond’s credit rating. The bond covenants are aimed at providing investors with reasonable assurances of the issuer’s fealty to its obligations under the bond, but not so much as to disenable it from running its business effectively. Failure to abide by the covenants is, thus, a negative circumstance.

The restrictiveness of the bond’s covenants will vary. Secured, or asset-backed, securities will have less restrictive covenants than unsecured issues. Furthermore, lower rated, non-investment grade, bonds are likely to be more restrictive and more complex, and hence will require a more careful reading prior to purchase and investment. Evaluation of these riskier securities’ covenants is relatively more important than in the case of investment grade bonds. Moody’s places some emphasis in the determination of its ratings for high-yield bonds on the issue’s covenants. High yield bonds tend to attract more sophisticated investors who are capable of studying the technical terms of the covenants; moreover, many such issues are placed privately among institutional investors.

Investment grade bonds will typically contain three standard covenants. First, there may be a covenant regarding “liens,” which assure the investor that no other party may obtain a “senior” (prior) claim to the asset (or collateral) subsequent to the bond’s issuance. Under the law, a lien is a claim by a person upon another person’s property for purposes of securing payment of a debt or the fulfillment of an obligation. If there is a prior lien on a property, no other person can subsequently make a claim on the same property. By manner of another example, when you buy a house, your attorney will conduct a “lien search,” to be sure that no one else owns the house except the seller with whom you are dealing.

Next, a covenant will protect against any reduction in seniority of the bond in case of a merger of the issuer with another corporation. This covenant will ensure that the bond is paid off first in any case.

Finally, another covenant may address the sale of an underlying asset – in the case of a secured bond. Obviously, should an asset underlying a collateralized bond be sold, the bond’s financial status will change markedly. Such assets ought not to be sold unless the bond is also redeemed.

There is no doubt that credit ratings are critical to pricing primary and secondary market issues. Ratings influence both the coupon rates of interest in the primary market, and market yields, or yields-to-maturity in the secondary markets.